Artist's

impression of Planet Nine eclipsing the central Milky Way, with the Sun

in the distance; Neptune's orbit is shown as a small ellipse around the

Sun

| |

| Orbital characteristics | |

|---|---|

| 400–800 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.2–0.5 |

| Inclination | 15°–25° |

| 150° (est.) | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Mass | 5–10 M⊕ (est.) |

| >22.5 (est.) | |

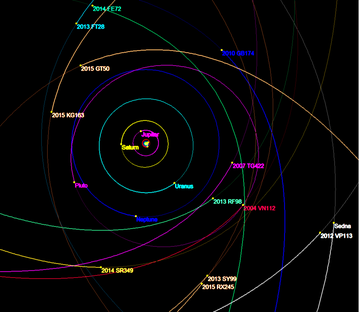

Planet Nine is a hypothetical planet in the outer region of the Solar System. Its gravitational effects could explain the unusual clustering of orbits for a group of extreme trans-Neptunian objects (eTNOs), bodies beyond Neptune that orbit the Sun at distances averaging more than 250 times that of the Earth. These eTNOs tend to make their closest approaches to the Sun in one sector, and their orbits are similarly tilted. These improbable alignments suggest that an undiscovered planet may be shepherding the orbits of the most distant known Solar System objects.

This undiscovered super-Earth-sized planet would have a predicted mass of five to ten times that of the Earth, and an elongated orbit 400 to 800 times as far from the Sun as the Earth. Konstantin Batygin and Michael E. Brown suggest that Planet Nine could be the core of a giant planet that was ejected from its original orbit by Jupiter during the genesis of the Solar System. Others propose that the planet was captured from another star, was once a rogue planet, or that it formed on a distant orbit and was pulled into an eccentric orbit by a passing star.

As of the end of 2018, no observation of Planet Nine had been announced. While sky surveys such as Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) and Pan-STARRS did not detect Planet Nine, they have not ruled out the existence of a Neptune-diameter object in the outer Solar System. The ability of these past sky surveys to detect Planet Nine were dependent on its location and characteristics. Further surveys of the remaining regions are ongoing using NEOWISE and the 8-meter Subaru Telescope. Unless Planet Nine is observed, its existence is purely conjectural. Several alternative theories have been proposed to explain the observed clustering of TNOs.

History

Following the discovery of Neptune in 1846, there was considerable speculation that another planet might exist beyond its orbit. The best-known of these theories predicted the existence of a distant planet that was influencing the orbits of Uranus and Neptune. After extensive calculations Percival Lowell predicted the possible orbit and location of the hypothetical trans-Neptunian planet and began an extensive search for it in 1906. He called the hypothetical object Planet X, a name previously used by Gabriel Dallet. Clyde Tombaugh continued Lowell's search and in 1930 discovered Pluto, but it was soon determined to be too small to qualify as Lowell's Planet X. After Voyager 2's flyby of Neptune in 1989, the difference between Uranus' predicted and observed orbit was determined to have been due to the use of a previously inaccurate mass of Neptune.Attempts to detect planets beyond Neptune by indirect means such as orbital perturbation date back to before the discovery of Pluto. Among the first was George Forbes who postulated the existence of two trans-Neptunian planets in 1880. One would have an average distance from the Sun, or semi-major axis, of 100 astronomical units (AU), 100 times that of the Earth. The second would have a semimajor axis of 300 AU. His work is considered similar to more recent Planet Nine theories in that the planets would be responsible for a clustering of the orbits of several objects, in this case the aphelion distances of periodic comets similar to that of the Jupiter-family comets.

The discovery of Sedna's peculiar orbit in 2004 led to speculation that it had encountered a massive body other than one of the eight known planets. Sedna's orbit is detached, with a perihelion distance of 76 AU that is too large to be due to gravitational interactions with Neptune. Several authors proposed that Sedna entered this orbit after encountering an unknown planet on a distant orbit, a member of the open cluster that formed with the Sun, or another star that later passed near the Solar System. The announcement in March 2014 of the discovery of a second sednoid with a perihelion distance of 80 AU, 2012 VP113, in a similar orbit led to renewed speculation that an unknown super-Earth remained in the distant Solar System.

At a conference in 2012, Rodney Gomes proposed that an undetected planet was responsible for the orbits of some eTNOs with detached orbits and the large semi-major axis Centaurs, small Solar System bodies that cross the orbits of the giant planets. The proposed Neptune-massed planet would be in a distant (1500 AU), eccentric (eccentricity 0.4), and inclined (inclination 40°) orbit. Like Planet Nine it would cause the perihelia of objects with semi-major axes greater than 300 AU to oscillate, delivering some into planet-crossing orbits and others into detached orbits like that of Sedna. An article by Gomes, Soares, and Brasser was published in 2015, detailing their arguments.

In 2014, astronomers Chad Trujillo and Scott S. Sheppard noted the similarities in the orbits of Sedna and 2012 VP113 and several other eTNOs. They proposed that an unknown planet in a circular orbit between 200 and 300 AU was perturbing their orbits. Later, in 2015, Raúl and Carlos de la Fuente Marco argued that two massive planets in orbital resonance were necessary to produce the similarities of so many orbits.

Batygin and Brown hypothesis

In early 2016, California Institute of Technology's

Batygin and Brown described how the similar orbits of six eTNOs could

be explained by Planet Nine and proposed a possible orbit for the

planet. This hypothesis could also explain eTNOs with orbits perpendicular to the inner planets and others with extreme inclinations, and had been offered as an explanation of the tilt of the Sun's axis.

Orbit

Planet Nine is hypothesized to follow an elliptical orbit around the Sun with an eccentricity of 0.2 to 0.5. The planet's semi-major axis is estimated to be 400 AU to 800 AU, roughly 13 to 26 times the distance from Neptune to the Sun. Its inclination to the ecliptic, the plane of the Earth's orbit, is projected to be 15° to 25°. The aphelion, or farthest point from the Sun, would be in the general direction of the constellation of Taurus, whereas the perihelion, the nearest point to the Sun, would be in the general direction of the southerly areas of Serpens (Caput), Ophiuchus, and Libra. Brown thinks that if Planet Nine is confirmed to exist, a probe could reach it in as little as 20 years by using a powered slingshot trajectory around the Sun.

Mass and radius

The planet is estimated to have 5 to 10 times the mass of Earth and a radius of 2 to 4 times Earth's. Brown thinks that if Planet Nine exists, its mass is sufficient to clear its orbit

of large bodies in 4.6 billion years, the age of the Solar System, and

that its gravity dominates the outer edge of the Solar System, which is

sufficient to make it a planet by current definitions. Astronomer Jean-Luc Margot has also stated that Planet Nine satisfies his criteria and would qualify as a planet if and when it is detected.

Origin

Several possible origins for Planet Nine have been examined including

its ejection from the neighborhood of the known giant planets, capture

from another star, and in situ

formation. In their initial article, Batygin and Brown proposed that

Planet Nine formed closer to the Sun and was ejected into a distant

eccentric orbit following a close encounter with Jupiter or Saturn during the nebular epoch. The gravity of a nearby star, or drag from the gaseous remnants of the Solar nebula,

then reduced the eccentricity of its orbit. This raised its perihelion,

leaving it in a very wide but stable orbit beyond the influence of the

other planets. Had it not been flung into the Solar System's farthest reaches, Planet Nine could have accreted more mass from the proto-planetary disk and developed into the core of a gas giant. Instead, its growth was halted early, leaving it with a lower mass than Uranus or Neptune.

Dynamical friction from a massive belt of planetesimals

could also enable Planet Nine's capture in a stable orbit. Recent

models propose that a 60–130 Earth mass disk of planetesimals could have

formed as the gas was cleared from the outer parts of the

proto-planetary disk.

As Planet Nine passed through this disk its gravity would alter the

paths of the individual objects in a way that reduced Planet Nine's

velocity relative to it. This would lower the eccentricity of Planet

Nine and stabilize its orbit. If this disk had a distant inner edge,

100–200 AU, a planet encountering Neptune would have a 20% chance of

being captured in an orbit similar to that proposed for Planet Nine,

with the observed clustering more likely if the inner edge is at 200 AU.

Unlike the gas nebula, the planetesimal disk is likely to have been

long lived, potentially allowing a later capture.

Planet Nine could have been captured from outside the Solar

System during a close encounter between the Sun and another star. If a

planet was in a distant orbit around this star, three-body

interactions during the encounter could alter the planet's path,

leaving it in a stable orbit around the Sun. A planet originating in a

system without Jupiter-massed planets could remain in a distant

eccentric orbit for a longer time, increasing its chances of capture. The wider range of possible orbits would reduce the odds of its capture in a relatively low inclination orbit to 1–2 percent.

This process could also occur with rogue planets, but the likelihood of

their capture is much smaller, with only 0.05–0.10% being captured in

orbits similar to that proposed for Planet Nine.

An encounter with another star could also alter the orbit of a

distant planet, shifting it from a circular to an eccentric orbit. The in situ formation of a planet at this distance would require a very massive and extensive disk, or the outward drift of solids in a dissipating disk forming a narrow ring from which the planet accreted over a billion years.

If a planet formed at such a great distance while the Sun was in its

original cluster, the probability of it remaining bound to the Sun in a

highly eccentric orbit is roughly 10%.

A previous article reported that if the massive disk extended beyond 80

AU some objects scattered outward by Jupiter and Saturn would have been

left in high inclination (inc > 50°), low eccentricity orbits which

have not been observed.

An extended disk would also have been subject to gravitational

disruption by passing stars and by mass loss due to photoevaporation

while the Sun remained in the open cluster where it formed.

Evidence

The gravitational influence of Planet Nine would explain four peculiarities of the Solar System:

- The clustering of the orbits of eTNOs;

- The high perihelia of objects like 90377 Sedna that are detached from Neptune's influence;

- The high inclinations of eTNOs with orbits roughly perpendicular to the orbits of the eight known planets;

- High-inclination trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) with semi-major axis less than 100 AU.

Planet Nine was initially proposed to explain the clustering of

orbits, via a mechanism that would also explain the high perihelia of

objects like Sedna. The evolution of some of these objects into

perpendicular orbits was unexpected, but found to match objects

previously observed. The orbits of some objects with perpendicular

orbits were later found to evolve toward smaller semimajor axes when the

other planets were included in simulations. Although other mechanisms

have been offered for many of these peculiarities, the gravitational

influence of Planet Nine is the only one that explains all four. The

gravity of Planet Nine could also increase the inclinations of other

objects that cross its orbit, however, leaving the short-period comets with a broader inclination distribution than is observed.

Previously Planet Nine was hypothesized to be responsible for the 6

degree tilt of the Sun's axis relative to the orbits of the planets. Recent updates to its predicted orbit and mass limit this shift to ~1 degree.

Observations: Orbital clustering of high perihelion objects

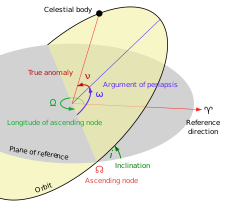

Diagram illustrating the true anomaly, argument of periapsis, longitude of ascending node, and inclination of a celestial body.

The clustering of the orbits of TNOs with large semi-major axes was

first described by Trujillo and Sheppard, who noted similarities between

the orbits of Sedna and 2012 VP113.

Without the presence of Planet Nine, these orbits should be distributed

randomly, without preference for any direction. Upon further analysis,

Trujillo and Sheppard observed that the arguments of perihelion of 12 TNOs with perihelia greater than 30 AU and semi-major axes greater than 150 AU

were clustered near zero degrees, meaning that they rise through the

ecliptic when they are closest to the sun. Trujillo and Sheppard

proposed that this alignment was caused by a massive unknown planet

beyond Neptune via the Kozai mechanism.

For objects with similar semi-major axes the Kozai mechanism would

confine their arguments of perihelion to near 0 or 180 degrees. This

confinement allows objects with eccentric and inclined orbits to avoid

close approaches to the planet because they would cross the plane of the

planet's orbit at their closest and farthest points from the Sun, and

cross the planet's orbit when they are well above or below its orbit.

Trujillo and Sheppard's hypothesis about how the objects would be

aligned by the Kozai mechanism has been supplanted by further analysis

and evidence.

Batygin and Brown, looking to refute the mechanism proposed by

Trujillo and Sheppard, also examined the orbits of the TNOs with large

semi-major axes.

After eliminating the objects in Trujillo and Sheppard's original

analysis that were unstable due to close approaches to Neptune or were

affected by Neptune's mean-motion resonances, Batygin and Brown determined that the arguments of perihelion for the remaining six objects (Sedna, 2012 VP113, 2004 VN112, 2010 GB174, 2000 CR105, and 2010 VZ98) were clustered around 318°±8°. This finding did not agree with how the Kozai mechanism would tend to align orbits with arguments of perihelion at 0° or 180°.

Orbital correlations among six distant trans-Neptunian objects led to the hypothesis.

Batygin and Brown also found that the orbits of the six eTNOs with

semi-major axes greater than 250 AU and perihelia beyond 30 AU (Sedna, 2012 VP113, 2004 VN112, 2010 GB174, 2007 TG422, and 2013 RF98) were aligned in space with their perihelia in roughly the same direction, resulting in a clustering of their longitudes of perihelion,

the location where they make their closest approaches to the Sun. The

orbits of the six objects were also tilted with respect to that of the ecliptic and approximately coplanar, producing a clustering of their longitudes of ascending nodes,

the directions where they each rise through the ecliptic. They

determined that there was only a 0.007% likelihood that this combination

of alignments was due to chance.

These six objects had been discovered by six different surveys on six

different telescopes. That made it less likely that the clumping might

be due to an observation bias such as pointing a telescope at a

particular part of the sky. The observed clustering should be smeared

out in a few hundred million years due to the locations of the perihelia

and the ascending nodes changing, or precessing, at differing rates due to their varied semi-major axes and eccentricities.

This indicates that the clustering could not be due to an event in the

distant past, such as a passing star, and is most likely maintained by

the gravitational field of an object orbiting the Sun.

Two of the six objects (2013 RF98 and 2004 VN112) also have very similar orbits and spectra. This has led to the suggestion that they were a binary object

disrupted near aphelion during an encounter with a distant object. The

disruption of a binary would require a relatively close encounter, which

becomes less likely at large distances from the Sun.

In a later article Trujillo and Sheppard noted a correlation

between the longitude of perihelion and the argument of perihelion of

the TNOs with semi-major axes greater than 150 AU. Those with a

longitude of perihelion of 0–120° have arguments of perihelion between

280–360°, and those with longitude of perihelion between 180° and 340°

have arguments of perihelion between 0° and 40°. The statistical

significance of this correlation was 99.99%. They suggested that the

correlation is due to the orbits of these objects avoiding close

approaches to a massive planet by passing above or below its orbit.

A 2017 article by Carlos and Raul de la Fuente Marcos noted that

distribution of the distances to the ascending nodes of the eTNOs, and

those of centaurs and comets with large semi-major axes, may be bimodal. They suggest it is due to the eTNOs avoiding close approaches to a planet with a semi-major axis of 300–400 AU.

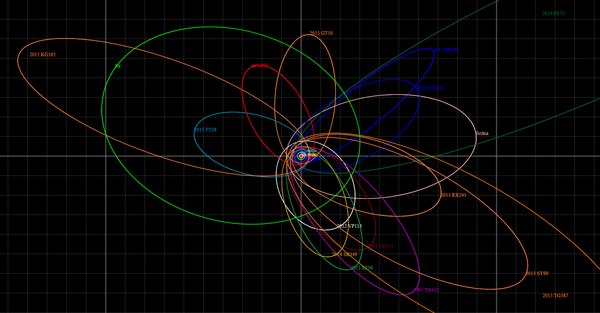

The extreme trans-Neptunian object orbits

Six original and eight additional eTNO objects orbits with current positions near their perihelion in purple, with hypothetical Planet Nine orbit in green

Simulations: Observed clustering reproduced

The clustering of the orbits of eTNOs and raising of their perihelia

is reproduced in simulations that include Planet Nine. In simulations

conducted by Batygin and Brown, swarms of objects with large semi-major

axes that began with random orientations were sculpted into roughly collinear

and coplanar groups of spatially confined orbits by a massive distant

planet in a highly eccentric orbit. The objects' perihelia tended to

point in the same direction and the objects' orbits tended to align in

the same plane. Many of these objects entered high-perihelion orbits

like Sedna and, unexpectedly, some entered perpendicular orbits that

Batygin and Brown later noticed had been previously observed.

In their original analysis Batygin and Brown found that the

distribution of the orbits of the first six eTNOs was best reproduced in

simulations using a 10 Earth mass planet in the following orbit:

- Semi-major axis a ≈ 700 AU (orbital period 7001.5=18,520 years)

- Eccentricity e ≈ 0.6, (perihelion ≈ 280 AU, aphelion ≈ 1,120 AU)

- Inclination i ≈ 30° to the ecliptic

- Longitude of the ascending node Ω ≈ 94°.

- Argument of perihelion ω ≈ 141° and longitude of perihelion ϖ = 235°±12°

These parameters for Planet Nine produce different simulated effects

on TNOs. Objects with semi-major axis greater than 250 AU are strongly

anti-aligned with Planet Nine, with perihelia opposite Planet Nine's

perihelion. Objects with semi-major axes between 150 AU and 250 AU are

weakly aligned with Planet Nine, with perihelia in the same direction as

Planet Nine's perihelion. Little effect is found on objects with

semi-major axes less than 150 AU. The simulations also revealed that objects with semimajor axis greater than 250 AU could have stable, aligned orbits if they had lower eccentricities. These objects have yet to be observed.

Other possible orbits for Planet Nine were also examined, with semi-major axes between 400 AU and 1500 AU,

eccentricites up to 0.8, and a wide range of inclinations. These orbits

yield varied results. Batygin and Brown found that orbits of the eTNOs

were more likely to have similar tilts if Planet Nine had a higher

inclination, but anti-alignment also decreased.

Simulations by Becker et al. showed that their orbits were more stable

if Planet Nine had a smaller eccentricity, but that anti-alignment was

more likely at higher eccentricities.

Lawler et al. found that the population captured in orbital resonances

with Planet Nine was smaller if it had a circular orbit, and that fewer

objects reached high inclination orbits.

Investigations by Cáceres et al. showed that the orbits of the eTNOs

were better aligned if Planet Nine had a lower perihelion orbit, but its

perihelion would need to be higher than 90 AU. Later investigations by Batygin et al. found that higher eccentricity orbits reduced the average tilts of the eTNOs orbits.

While there are many possible combinations of orbital parameters and

masses for Planet Nine, none of the alternative simulations have been

better at predicting the observed alignment of objects in the Solar

System. The discovery of additional distant Solar System objects would

allow astronomers to make more accurate predictions about the orbit of

the hypothesized planet. These may also provide further support for, or

refutation of, the Planet Nine hypothesis.

Dynamics: How Planet Nine modifies the orbits of eTNOs

Long term evolution of eTNOs induced by Planet Nine for objects with semi-major axis of 250 AU. Blue: anti-aligned, Red: aligned, Green: metastable, Orange: circulating. Crossing orbits above black line.

Planet Nine modifies the orbits of eTNOs via a combination of effects. On very long timescales Planet Nine exerts a torque on the orbits of the eTNOs that varies with the alignment of their orbits with Planet Nine's. The resulting exchanges of angular momentum

cause the perihelia to rise, placing them in Sedna-like orbits, and

later fall, returning them to their original orbits after several

hundred million years. The motion of their directions of perihelion also

reverses when their eccentricities are small, keeping the objects

anti-aligned, see blue curves on diagram, or aligned, red curves. On

shorter timescales mean-motion resonances with Planet Nine provides

phase protection, which stabilizes their orbits by slightly altering the

objects' semi-major axes, keeping their orbits synchronized with Planet

Nine's and preventing close approaches. The gravity of Neptune and the

other giant planets, and the inclination of Planet Nine's orbit, weaken

this protection. This results in a chaotic

variation of semi-major axes as objects hop between resonances,

including high order resonances such as 27:17, on million-year

timescales. The mean-motion resonances may not be necessary for the survival of eTNOs if they and Planet Nine are both on inclined orbits. The orbital poles of the objects precess around, or circle, the pole of the Solar System's Laplace plane.

At large semi-major axes the Laplace plane is warped toward the plane

of Planet Nine's orbit. This causes orbital poles of the eTNOs on

average to be tilted toward one side and their longitudes of ascending

nodes to be clustered.

Objects in perpendicular orbits with large semi-major axis

The

orbits of the five objects with high-inclination orbits (nearly

perpendicular to the ecliptic) are shown here as cyan ellipses with the

hypothetical Planet Nine in orange.

Planet Nine can deliver eTNOs into orbits roughly perpendicular to the ecliptic. Several objects with high inclinations, greater than 50°, and large semi-major axes, above 250 AU, have been observed. These orbits are produced when some low inclination eTNOs enter a secular resonance

with Planet Nine upon reaching low eccentricity orbits. The resonance

causes their eccentricities and inclinations to increase, delivering the

eTNOs into perpendicular orbits with low perihelia where they are more

readily observed. The eTNOs then evolve into retrograde

orbits with lower eccentricities, after which they pass through a

second phase of high eccentricity perpendicular orbits, before returning

to low eccentricity and inclination orbits. The secular resonance with

Planet Nine involves a linear combination

of the orbit's arguments and longitudes of perihelion: Δϖ – 2ω. Unlike

the Kozai mechanism this resonance causes objects to reach their maximum

eccentricities when in nearly perpendicular orbits. In simulations

conducted by Batygin and Morbidelli this evolution was relatively

common, with 38% of stable objects undergoing it at least once.

The arguments of perihelion of these objects are clustered near or

opposite Planet Nine's and their longitudes of ascending node are

clustered around 90° in either direction from Planet Nine's when they

reach low perihelia.

This is in rough agreement with observations with the differences

attributed to distant encounters with the known giant planets.

Orbits of high-inclination objects

A population of high-inclination TNOs with semi-major axes less than

100 AU may be generated by the combined effects of Planet Nine and the

other giant planets. The eTNOs that enter perpendicular orbits have

perihelia low enough for their orbits to intersect those of Neptune or

the other giant planets. An encounter with one of these planets can

lower an eTNO's semi-major axis to below 100 AU, where the object's

orbits is no longer controlled by Planet Nine, leaving it in an orbit

like 2008 KV42.

The predicted orbital distribution of the longest lived of these

objects is nonuniform. Most would have orbits with perihelia ranging

from 5 AU to 35 AU and inclinations below 110 degree; beyond a gap with

few objects are would be others with inclinations near 150 degrees and

perihelia near 10 AU. Previously it was proposed that these objects originated in the Oort Cloud, a theoretical cloud of icy planetesimals surrounding the Sun at distances of 2,000 to 200,000 AU.

Oort cloud and comets

Planet Nine would alter the source regions and the inclination

distribution of comets. In simulations of the migration of the giant

planets described by the Nice model fewer objects are captured in the Oort cloud

when Planet Nine is included. Other objects would be captured in a

cloud of objects dynamically controlled by Planet Nine. This Planet Nine

cloud, made up of the eTNOs and the perpendicular objects, would extend

from semimajor axes of 200 AU to 3000 AU and contain roughly 0.3–0.4

Earth masses.

When the perihelia of objects in the Planet Nine cloud drop low enough

for them to encounter the other planets some would be scattered into

orbits that enter the inner Solar System where they could be observed as

comets. If Planet Nine exists these would make up roughly one third of

the Halley-type comets. Planet Nine would also alter the orbits of the scattering disk objects,

those with semi-major axes greater than 50 AU and perihelia near

Neptune's orbit, that cross its orbit, increasing their inclinations.

This would increase the inclinations of the Jupiter-family comets derived from that population leaving them with a broader inclination distribution than is observed. Recent estimates of a smaller mass and eccentricity for Planet Nine would reduce its effect on these inclinations.

Reception

Batygin was cautious in interpreting the results of the simulation

developed for his and Brown's research article, saying, "Until Planet

Nine is caught on camera it does not count as being real. All we have

now is an echo." Brown put the odds for the existence of Planet Nine at about 90%. Greg Laughlin, one of the few researchers who knew in advance about this article, gives an estimate of 68.3%.

Other skeptical scientists demand more data in terms of additional KBOs

to be analyzed or final evidence through photographic confirmation. Brown, though conceding the skeptics' point, still thinks that there is enough data to mount a search for a new planet.

The Planet Nine hypothesis is supported by several astronomers and academics. Jim Green, director of NASA's Science Mission Directorate, said, "the evidence is stronger now than it's been before". But Green also cautioned about the possibility of other explanations for the observed motion of distant eTNOs and, quoting Carl Sagan, he said, "extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence." Massachusetts Institute of Technology Professor Tom Levenson

concluded that, for now, Planet Nine seems the only satisfactory

explanation for everything now known about the outer regions of the

Solar System. Astronomer Alessandro Morbidelli, who reviewed the research article for The Astronomical Journal, concurred, saying, "I don't see any alternative explanation to that offered by Batygin and Brown."

Astronomer Renu Malhotra

remains agnostic about Planet Nine, but noted that she and her

colleagues have found that the orbits of eTNOs seem tilted in a way that

is difficult to otherwise explain. "The amount of warp we see is just

crazy," she said. "To me, it's the most intriguing evidence for Planet

Nine I've run across so far."

Other authorities have varying degrees of skepticism. American astrophysicist Ethan Siegel,

who previously speculated that planets may have been ejected from the

Solar System during an early dynamical instability, is skeptical of the

existence of an undiscovered planet in the Solar System.

In a 2018 article discussing a survey that did not find evidence of

clustering of the eTNOs' orbits he suggests the previously observed

clustering could have been the result of observing bias and claims most

scientists think Planet Nine does not exist. Planetary scientist Hal Levison

thinks that the chance of an ejected object ending up in the inner Oort

cloud is only about 2%, and speculates that many objects must have been

thrown past the Oort cloud if one has entered a stable orbit.

Alternative hypotheses

Temporary or coincidental clustering

The results of the Outer Solar System Survey (OSSOS) suggest that the

observed clustering is the result of a combination of observing bias

and small number statistics. OSSOS, a well-characterized survey of the

outer Solar System with known biases, observed eight objects with

semi-major axis > 150 AU with orbits oriented on a wide range of

directions. After accounting for the observational biases of the survey,

no evidence for the arguments of perihelion (ω) clustering identified

by Trujillo and Sheppard was seen, and the orientation of the orbits of the objects with the largest semi-major axis was statistically consistent with random.

This result differed from an analysis of discovery biases in the

previously observed eTNOs by Mike Brown. He found that after observing

biases were accounted for the clustering of longitudes of perihelion of

10 known eTNOs would be observed only 1.2% of the time if their actual

distribution was uniform. When combined with the odds of the observed

clustering of the arguments of perihelion the probability was 0.025%.

A later analysis of the discovery biases of 14 eTNOs by Brown and

Batygin found a probability of the observed clustering of the longitudes

of perihelion and the orbital pole locations of 0.2%.

Simulations of 15 known objects evolving under the influence of

Planet Nine also revealed differences with observations. Cory Shankman

and his colleagues included Planet Nine in a simulation of many clones

(objects with similar orbits) of 15 objects with semi-major axis more than

150 AU and perihelion more than 30 AU.

While they observed alignment of the orbits opposite that of Planet

Nine's for the objects with semi-major axis greater than 250 AU,

clustering of the arguments of perihelion was not seen. Their

simulations also showed that the perihelia of the eTNOs rose and fell

smoothly, leaving many with perihelion distances between 50 AU and 70 AU

where none had been observed, and predicted that there would be many

other unobserved objects.

These included a large reservoir of high-inclination objects that would

have been missed due to most observations being at small inclinations,

and a large population of objects with perihelia so distant that they

would be too faint to observe. Many of the objects were also ejected

from the Solar System after encountering the other giant planets. The

large unobserved populations and the loss of many objects led Shankman

et al. to estimate that the mass of the original population was tens of

Earth masses, requiring that a much larger mass had been ejected during

the early Solar System.[L]

Shankman et al. concluded that the existence of Planet Nine is unlikely

and that the currently observed alignment of the existing eTNOs is a

temporary phenomenon that will disappear as more objects are detected.

Inclination instability in a massive disk

Ann-Marie Madigan and Michael McCourt postulate that an inclination instability in a distant massive belt is responsible for the alignment of the arguments of perihelion of the eTNOs.

An inclination instability could occur in a disk of particles with high

eccentricity orbits (e>0.6) around a central body, such as the Sun.

The self-gravity of this disk would cause its spontaneous organization,

increasing the inclinations of the objects and aligning the arguments of

perihelion, forming it into a cone above or below the original plane.

This process would require an extended time and significant mass of the

disk, on the order of a billion years for a 1–10 Earth-mass disk.

While an inclination instability could align the arguments of

perihelion and raise perihelia, producing detached objects, it would not

align the longitudes of perihelion.

Mike Brown considers Planet Nine a more probable explanation, noting

that current surveys have not revealed a large enough scattered-disk to

produce an "inclination instability".

In Nice model simulations of the Solar System that included the

self-gravity of the planetesimal disk an inclination instability did not

occur. Instead, the simulation produced a rapid precession of the

objects' orbits and most of the objects were ejected on too short of a

timescale for an inclination instability to occur.

Shepherding by a massive disk

Antranik Sefilian and Jihad Touma propose that a massive disk of

moderately eccentric TNOs is responsible for the clustering of the

longitudes of perihelion of the eTNOs. Their predicted 10 Earth-mass

disk would contain TNOs with aligned orbits and eccentricities that

increased with their semimajor axes ranging from zero to 0.165. The

gravitational effects of this disk would offset the forward precession

driven by the giant planets so that the orbital orientations of its

individual objects are maintained. The orbits of objects with high

eccentricities, such as the observed eTNOs, would be stable and have

roughly fixed orientations, or longitudes of perihelion, if their orbits

were anti-aligned with this disk.

Although Brown thinks the proposed disk could explain the observed

clustering of the eTNOs, he finds it implausible that the disk could

survive over the age of the Solar System.

Batygin thinks that there is insufficient mass in the Kuiper belt to

explain the formation of the disk and asks "why would the protoplanetary

disk end near 30 AU and restart beyond 100 AU?"

Planet in lower eccentricity orbit

The Planet Nine hypothesis includes a set of predictions about the

mass and orbit of the planet. An alternative theory predicts a planet

with different orbital parameters. Malhotra, Kathryn Volk, and Xianyu

Wang have proposed that the four detached objects with the longest

orbital periods, those with perihelia beyond 40 AU and semi-major axes greater than 250 AU, are in n:1 or n:2 mean-motion resonances with a hypothetical planet. Two other objects with semi-major axes greater than 150 AU

are also potentially in resonance with this planet. Their proposed

planet could be on a lower eccentricity, low inclination orbit, with

eccentricity e less than 0.18 and inclination i ≈ 11°. The eccentricity is limited in this case by the requirement that close approaches of 2010 GB174 to the planet are avoided. If the eTNOs are in periodic orbits of the third kind,

with their stability enhanced by the libration of their arguments of

perihelion, the planet could be in a higher inclination orbit, with i

≈ 48°. Unlike Batygin and Brown, Malhotra, Volk and Wang do not specify

that most of the distant detached objects would have orbits

anti-aligned with the massive planet.

Alignment due to the Kozai mechanism

Trujillo and Sheppard argued in 2014 that a massive planet in a circular orbit with an average distance between 200 AU and 300 AU

was responsible for the clustering of the arguments of perihelion of

twelve TNOs with large semi-major axes. Trujillo and Sheppard identified

a clustering near zero degrees of the arguments of perihelion of the

orbits of twelve TNOs with perihelia greater than 30 AU and semi-major axes greater than 150 AU.

After numerical simulations showed that the arguments of perihelion

should circulate at varying rates, leaving them randomized after

billions of years, they suggested that a massive planet in a circular

orbit at a few hundred astronomical units was responsible for this

clustering.

This massive planet would cause the arguments of perihelion of the TNOs

to librate about 0° or 180° via the Kozai mechanism so that their

orbits crossed the plane of the planet's orbit near perihelion and

aphelion, the closest and farthest points from the planet. In numerical simulations including a 2–15 Earth mass body in a circular low-inclination orbit between 200 AU and 300 AU the arguments of perihelia of Sedna and 2012 VP113

librated around 0° for billions of years (although the lower perihelion

objects did not) and underwent periods of libration with a Neptune mass

object in a high inclination orbit at 1,500 AU.

Another process such as a passing star would be required to account for

the absence of objects with arguments of perihelion near 180°.

These simulations showed the basic idea of how a single large

planet can shepherd the smaller TNOs into similar types of orbits. They

were basic proof of concept simulations that did not obtain a unique

orbit for the planet as they state there are many possible orbital

configurations the planet could have.

Thus they did not fully formulate a model that successfully

incorporated all the clustering of the eTNOs with an orbit for the

planet.

But they were the first to notice there was a clustering in the orbits

of TNOs and that the most likely reason was from an unknown massive

distant planet. Their work is very similar to how Alexis Bouvard

noticed Uranus' motion was peculiar and suggested that it was likely

gravitational forces from an unknown 8th planet, which led to the

discovery of Neptune.

Raúl and Carlos de la Fuente Marcos proposed a similar model but with two distant planets in resonance. An analysis by Carlos and Raúl de la Fuente Marcos with Sverre J. Aarseth

confirmed that the observed alignment of the arguments of perihelion

could not be due to observational bias. They speculated that instead it

was caused by an object with a mass between that of Mars and Saturn that

orbited at some 200 AU from the Sun. Like

Trujillo and Sheppard they theorized that the TNOs are kept bunched

together by a Kozai mechanism and compared their behavior to that of Comet 96P/Machholz under the influence of Jupiter.

They also struggled to explain the orbital alignment using a model with

only one unknown planet, and therefore suggested that this planet is

itself in resonance with a more-massive world about 250 AU from the Sun.

In their article, Brown and Batygin noted that alignment of arguments

of perihelion near 0° or 180° via the Kozai mechanism requires a ratio

of the semi-major axes nearly equal to one, indicating that multiple

planets with orbits tuned to the data set would be required, making this

explanation too unwieldy.

Detection attempts

Visibility and location

Due to its extreme distance from the Sun, Planet Nine would reflect little sunlight, potentially evading telescope sightings. It is expected to have an apparent magnitude fainter than 22, making it at least 600 times fainter than Pluto.

If Planet Nine exists and is close to perihelion, astronomers could

identify it based on existing images. At aphelion, the largest

telescopes would be required, but if the planet is currently located in

between, many observatories could spot Planet Nine. Statistically, the planet is more likely to be closer to its aphelion at a distance greater than 600 AU. This is because objects move more slowly when near their aphelion, in accordance with Kepler's second law.

Planet Nine is predicted to be brighter, magnitude 21–22, if it is near

the small end of its estimated mass range because it would need to be

closer to have the same dynamical effect.

Searches of existing data

The search of databases of stellar objects

by Batygin and Brown has already excluded much of the sky along Planet

Nine's predicted orbit. The remaining regions include the direction of

its aphelion, where it would be too faint to be spotted by these

surveys, and near the plane of the Milky Way, where it would be difficult to distinguish from the numerous stars. This search included the archival data from the Catalina Sky Survey to magnitude c. 19, Pan-STARRS to magnitude 21.5, and infrared data from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) satellite.

Other researchers have been conducting searches of existing data. David Gerdes, who helped develop the camera used in the Dark Energy Survey, claims that software designed to identify distant Solar System objects such as 2014 UZ224 could find Planet Nine if it was imaged as part of that survey, which covered a quarter of the southern sky. Michael Medford and Danny Goldstein, graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley, are also examining archived data using a technique that combines images taken at different times. Using a supercomputer

they will offset the images to account for the calculated motion of

Planet Nine, allowing many faint images of a faint moving object to be

combined to produce a brighter image.

A search combining multiple images collected by WISE and NEOWISE data

has also been conducted without detecting Planet Nine. This search

covered regions of the sky away from the galactic plane at the "W1"

wavelength (the 3.4 μm wavelength used by WISE) and is estimated to be

able to detect a 10-Earth mass object out to 800–900 AU.

Ongoing searches

Because the planet is predicted to be visible in the Northern Hemisphere, the primary search is expected to be carried out using the Subaru Telescope, which has both an aperture large enough to see faint objects and a wide field of view to shorten the search.

Two teams of astronomers—Batygin and Brown, as well as Trujillo and

Sheppard—are undertaking this search together, and both teams expect the

search to take up to five years. Brown and Batygin initially narrowed the search for Planet Nine down to roughly 2,000 square degrees of sky near Orion, a swath of space that Batygin thinks could be covered in about 20 nights by the Subaru Telescope. Subsequent refinements by Batygin and Brown have reduced the search space to 600–800 square degrees of sky. In December 2018, they spent 4 half–nights and 3 full nights observing with the Subaru Telescope.

Radiation

Although a distant planet such as Planet Nine would reflect little

light, it would still be radiating the heat from its formation as it

cools due to its large mass. At its estimated temperature of 47 K

(−226.2 °C) the peak of its emissions would be at infrared wavelengths. This radiation signature could be detected by Earth-based submillimeter telescopes, such as ALMA, and a search could be conducted by cosmic microwave background experiments operating at mm wavelengths. Jim Green of NASA's Science Mission Directorate is optimistic that it could be observed by the James Webb Space Telescope, the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, that is expected to be launched in 2021.

Citizen science

The Zooniverse Backyard Worlds

project, started in February 2017, is using archival data from the WISE

spacecraft to search for Planet Nine. The project will also search for

substellar objects like brown dwarfs in the neighborhood of the Solar System.

32,000 animations of four images each, which constitute 3 per cent of

the WISE data, have been uploaded to the Backyard Worlds website. By

looking for moving objects in the animations, citizen scientists might

find Planet Nine.

In April 2017, using data from the SkyMapper telescope at Siding Spring Observatory, citizen scientists on the Zooniverse

platform reported four candidates for Planet Nine. These candidates

will be followed up on by astronomers to determine their viability.

The project, which started on 28 March 2017, completed their goals in

less than three days with around five million classifications by more

than 60,000 individuals.

Attempts to predict location

Cassini measurements of Saturn's orbit

Precise observations of Saturn's orbit using data from Cassini

suggest that Planet Nine could not be in certain sections of its

proposed orbit because its gravity would cause a noticeable effect on

Saturn's position. This data neither proves nor disproves that Planet

Nine exists.

An initial analysis by Fienga, Laskar, Manche, and Gastineau

using Cassini data to search for Saturn's orbital residuals, small

differences with its predicted orbit due to the Sun and the known

planets, was inconsistent with Planet Nine being located with a true anomaly,

the location along its orbit relative to perihelion, of −130° to −110°

or −65° to 85°. The analysis, using Batygin and Brown's orbital

parameters for Planet Nine, suggests that the lack of perturbations to

Saturn's orbit is best explained if Planet Nine is located at a true

anomaly of 117.8°+11°

−10°. At this location, Planet Nine would be approximately 630 AU from the Sun, with right ascension close to 2h and declination close to −20°, in Cetus. In contrast, if the putative planet is near aphelion it would be located near right ascension 3.0h to 5.5h and declination −1° to 6°.

−10°. At this location, Planet Nine would be approximately 630 AU from the Sun, with right ascension close to 2h and declination close to −20°, in Cetus. In contrast, if the putative planet is near aphelion it would be located near right ascension 3.0h to 5.5h and declination −1° to 6°.

A later analysis of Cassini data by astrophysicists

Matthew Holman and Matthew Payne tightened the constraints on possible

locations of Planet Nine. Holman and Payne developed a more efficient

model that allowed them to explore a broader range of parameters than

the previous analysis. The parameters identified using this technique to

analyze the Cassini data was then intersected with Batygin and Brown's

dynamical constraints on Planet Nine's orbit. Holman and Payne concluded

that Planet Nine is most likely to be located within 20° of RA = 40°,

Dec = −15°, in an area of the sky near the constellation Cetus.

William Folkner, a planetary scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), has stated that the Cassini

spacecraft is not experiencing unexplained deviations in its orbit

around Saturn. An undiscovered planet would affect the orbit of Saturn,

not Cassini. This could produce a signature in the measurements of Cassini, but JPL has seen no unexplained signatures in Cassini data.

Analysis of Pluto's orbit

An analysis in 2016 of Pluto's orbit by Holman and Payne found

perturbations much larger than predicted by Batygin and Brown's proposed

orbit for Planet Nine. Holman and Payne suggested three possible

explanations: systematic errors in the measurements of Pluto's orbit; an

unmodeled mass in the Solar System, such as a small planet in the range

of 60–100 AU (potentially explaining the Kuiper cliff); or a planet more massive or closer to the Sun instead of the planet predicted by Batygin and Brown.

Orbits of nearly parabolic comets

An analysis of the orbits of comets with nearly parabolic orbits identifies five new comets with hyperbolic orbits

that approach the nominal orbit of Planet Nine described in Batygin and

Brown's initial article. If these orbits are hyperbolic due to close

encounters with Planet Nine the analysis estimates that Planet Nine is

currently near aphelion with a right ascension of 83–90° and a

declination of 8–10°. Scott Sheppard, who is skeptical of this analysis, notes that many different forces influence the orbits of comets.

Attempts to predict semimajor axis

An analysis by Sarah Millholland and Gregory Laughlin identified a pattern of commensurabilities

(ratios between orbital periods of pairs of objects consistent with

both being in resonance with another object) of the eTNOs. They identify

five objects that would be near resonances with Planet Nine if had a

semi-major axis of 654 AU: Sedna (3:2), 2004 VN112 (3:1), 2012 VP113 (4:1), 2000 CR105 (5:1), and 2001 FP185 (5:1). They identify this planet as Planet Nine but propose a different orbit with an eccentricity e ≈ 0.5, inclination i

≈ 30°, argument of perihelion ω ≈ 150°, and longitude of ascending node

Ω ≈ 50° (the last differs from Brown and Batygin's value of 90°).

Carlos and Raul de la Fuente Marcos also note commensurabilities

among the known eTNOs similar to that of the Kuiper belt, where

accidental commensurabilities occur due to objects in resonances with

Neptune. They find that some of these objects would be in 5:3 and 3:1

resonances with a planet that had a semi-major axis of ≈700 AU.

Three objects with smaller semi-major axes near 172 AU (2013 UH15, 2016 QV89 and 2016 QU89)

have also been proposed to be in resonance with Planet Nine. These

objects would be in resonance and anti-aligned with Planet Nine if it

had a semi-major axis of 315 AU, below the range proposed by Batygin and

Brown. Alternatively, they could be in resonance with Planet Nine, but

have orbital orientations that circulate instead of being confined by

Planet Nine if it had a semi-major axis of 505 AU.

A later analysis by Elizabeth Bailey, Michael Brown and

Konstantin Batygin found that if Planet Nine is in an eccentric and

inclined orbit the capture of many of the eTNOs in higher order

resonances and their chaotic transfer between resonances prevent the

identification of Planet Nine's semi-major axis using current

observations. They also determined that the odds of the first six

objects observed being in N/1 or N/2 period ratios with Planet Nine are

less than 5% if it has an eccentric orbit.

Naming

Planet Nine does not have an official name and will not receive one

unless its existence is confirmed via imaging. Only two planets, Uranus

and Neptune, have been discovered in recorded history. However, a great

many minor planets, including dwarf planets, asteroids, and comets have been discovered and named. Consequently, there is a well-established process for naming newly discovered solar system objects. If Planet Nine is observed, the International Astronomical Union will certify a name, with priority usually given to a name proposed by its discoverers. It is likely to be a name chosen from Roman or Greek mythology.

In their original article, Batygin and Brown simply referred to the object as "perturber", and only in later press releases did they use "Planet Nine". They have also used the names "Jehoshaphat" and "George" for Planet Nine. Brown has stated: "We actually call it Phattie when we're just talking to each other."

In 2018, planetary scientist Alan Stern objected to the name Planet Nine,

saying, "It is an effort to erase Clyde Tombaugh's legacy and it's

frankly insulting", suggesting the name Planet X until its discovery.

He signed a statement with 34 other scientists saying, "We further

believe the use of this term [Planet Nine] should be discontinued in

favor of culturally and taxonomically neutral terms for such planets, such as Planet X, Planet Next, or Giant Planet Five." According to Brown, "'Planet X'

is not a generic reference to some unknown planet, but a specific

prediction of Lowell's which led to the (accidental) discovery of Pluto.

Our prediction is not related to this prediction."