Standing Buddha statue at the Tokyo National Museum. One of the earliest known representations of the Buddha, 1st–2nd century CE.

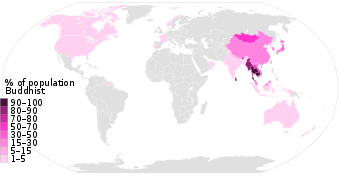

Buddhism is the world's fourth-largest religion with over 520 million followers, or over 7% of the global population, known as Buddhists.

Buddhism encompasses a variety of traditions, beliefs and spiritual practices largely based on original teachings attributed to the Buddha and resulting interpreted philosophies. Buddhism originated in ancient India as a Sramana tradition sometime between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE, spreading through much of Asia. Two major extant branches of Buddhism are generally recognized by scholars: Theravada (Pali: "The School of the Elders") and Mahayana (Sanskrit: "The Great Vehicle").

Most Buddhist traditions share the goal of overcoming suffering and the cycle of death and rebirth, either by the attainment of Nirvana or through the path of Buddhahood. Buddhist schools vary in their interpretation of the path to liberation, the relative importance and canonicity assigned to the various Buddhist texts, and their specific teachings and practices. Widely observed practices include taking refuge in the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha, observance of moral precepts, monasticism, meditation, and the cultivation of the Paramitas (virtues).

Theravada Buddhism has a widespread following in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia such as Myanmar and Thailand. Mahayana, which includes the traditions of Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren Buddhism, Shingon and Tiantai (Tendai), is found throughout East Asia.

Vajrayana, a body of teachings attributed to Indian adepts, may be viewed as a separate branch or as an aspect of Mahayana Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism, which preserves the Vajrayana teachings of eighth-century India, is practiced in the countries of the Himalayan region, Mongolia, and Kalmykia.

Life of the Buddha

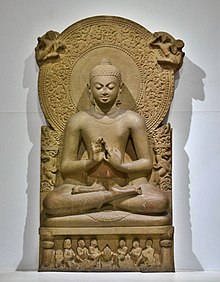

Buddha in Sarnath Museum (Dhammajak Mutra)

Buddhism is an Indian religion attributed to the teachings of the Buddha, supposedly born Siddhārtha Gautama, and also known as the Tathāgata ("thus-gone") and Sakyamuni

("sage of the Sakyas"). Early texts have his personal name as "Gautama"

or "Gotama" (Pali) without any mention of "Siddhārtha," ("Achieved the

Goal") which appears to have been a kind of honorific title when it does

appear. The details of Buddha's life are mentioned in many Early Buddhist Texts but are inconsistent, and his social background and life details are difficult to prove, the precise dates uncertain.

The evidence of the early texts suggests that he was born as Siddhārtha Gautama in Lumbini and grew up in Kapilavasthu, a town in the plains region of the modern Nepal-India border, and that he spent his life in what is now modern Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

Some hagiographic legends state that his father was a king named

Suddhodana, his mother was Queen Maya, and he was born in Lumbini

gardens.

However, scholars such as Richard Gombrich consider this a dubious

claim because a combination of evidence suggests he was born in the Shakyas community – one that later gave him the title Shakyamuni, and the Shakya

community was governed by a small oligarchy or republic-like council

where there were no ranks but where seniority mattered instead.

Some of the stories about Buddha, his life, his teachings, and claims

about the society he grew up in may have been invented and interpolated

at a later time into the Buddhist texts.

"The Great Departure", relic depicting Gautama leaving home, first or second century (Musée Guimet)

According to the Buddhist sutras, Gautama was moved by the innate suffering of humanity and its endless repetition

due to rebirth. He set out on a quest to end this repeated suffering.

Early Buddhist canonical texts and early biographies of Gautama state

that Gautama first studied under Vedic

teachers, namely Alara Kalama (Sanskrit: Arada Kalama) and Uddaka

Ramaputta (Sanskrit: Udraka Ramaputra), learning meditation and ancient

philosophies, particularly the concept of "nothingness, emptiness" from

the former, and "what is neither seen nor unseen" from the latter.

The gilded "Emaciated Buddha statue" in an Ubosoth in Bangkok representing the stage of his asceticism

Finding these teachings to be insufficient to attain his goal, he turned to the practice of asceticism. This too fell short of attaining his goal, and then he turned to the practice of dhyana, meditation. He famously sat in meditation under a Ficus religiosa tree now called the Bodhi Tree in the town of Bodh Gaya in the Gangetic plains region of South Asia. He gained insight into the workings of karma and his former lives, and attained enlightenment, certainty about the Middle Way (Skt. madhyamā-pratipad) as the right path of spiritual practice to end suffering (dukkha) from rebirths in Saṃsāra.

As a fully enlightened Buddha (Skt. samyaksaṃbuddha), he attracted followers and founded a Sangha (monastic order). Now, as the Buddha, he spent the rest of his life teaching the Dharma he had discovered, and died at the age of 80 in Kushinagar, India.

Buddha's teachings were propagated by his followers, which in the

last centuries of the 1st millennium BCE became over 18 Buddhist

sub-schools of thought, each with its own basket of texts containing different interpretations and authentic teachings of the Buddha; these over time evolved into many traditions of which the more well known and widespread in the modern era are Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism.

The problems of life: dukkha and saṃsāra

Four Noble Truths – dukkha and its ending

The Four Truths express the basic orientation of Buddhism: we crave and cling to impermanent states and things, which is dukkha, "incapable of satisfying" and painful. This keeps us caught in saṃsāra, the endless cycle of repeated rebirth, dukkha and dying again.

But there is a way to liberation from this endless cycle to the state of nirvana, namely following the Noble Eightfold Path.

The truth of dukkha is the basic insight that life in this mundane world, with its clinging and craving to impermanent states and things is dukkha, and unsatisfactory. Dukkha can be translated as "incapable of satisfying," "the unsatisfactory nature and the general insecurity of all conditioned phenomena"; or "painful." Dukkha

is most commonly translated as "suffering," but this is inaccurate,

since it refers not to episodic suffering, but to the intrinsically

unsatisfactory nature of temporary states and things, including pleasant

but temporary experiences. We expect happiness from states and things which are impermanent, and therefore cannot attain real happiness.

In Buddhism, dukkha is one of the three marks of existence, along with impermanence and anattā (non-self).

Buddhism, like other major Indian religions, asserts that everything is

impermanent (anicca), but, unlike them, also asserts that there is no

permanent self or soul in living beings (anattā). The ignorance or misperception (avijjā)

that anything is permanent or that there is self in any being is

considered a wrong understanding, and the primary source of clinging and

dukkha.

Dukkha arises when we crave (Pali: tanha) and cling to these changing phenomena. The clinging and craving produces karma, which ties us to samsara, the round of death and rebirth. Craving includes kama-tanha, craving for sense-pleasures; bhava-tanha, craving to continue the cycle of life and death, including rebirth; and vibhava-tanha, craving to not experience the world and painful feelings.

Dukkha ceases, or can be confined, when craving and clinging cease or are confined. This also means that no more karma is being produced, and rebirth ends. Cessation is nirvana, "blowing out," and peace of mind.

By following the Buddhist path to moksha, liberation,

one starts to disengage from craving and clinging to impermanent states

and things. The term "path" is usually taken to mean the Noble Eightfold Path, but other versions of "the path" can also be found in the Nikayas. The Theravada tradition regards insight into the four truths as liberating in itself.

The cycle of rebirth

Traditional Tibetan Buddhist Thangka depicting the Wheel of Life with its six realms

Saṃsāra

Saṃsāra means "wandering" or "world", with the connotation of cyclic, circuitous change.

It refers to the theory of rebirth and "cyclicality of all life,

matter, existence", a fundamental assumption of Buddhism, as with all

major Indian religions. Samsara in Buddhism is considered to be dukkha, unsatisfactory and painful, perpetuated by desire and avidya (ignorance), and the resulting karma.

The theory of rebirths, and realms in which these rebirths can

occur, is extensively developed in Buddhism, in particular Tibetan

Buddhism with its wheel of existence (Bhavacakra) doctrine. Liberation from this cycle of existence, nirvana, has been the foundation and the most important historical justification of Buddhism.

The later Buddhist texts assert that rebirth can occur in six

realms of existence, namely three good realms (heavenly, demi-god,

human) and three evil realms (animal, hungry ghosts, hellish). Samsara ends if a person attains nirvana, the "blowing out" of the desires and the gaining of true insight into impermanence and non-self reality.

Rebirth

Ramabhar Stupa in Kushinagar, Uttar Pradesh, India is regionally believed to be Buddha's cremation site.

Rebirth refers to a process whereby beings go through a succession of lifetimes as one of many possible forms of sentient life, each running from conception to death. In Buddhist thought, this rebirth does not involve any soul, because of its doctrine of anattā (Sanskrit: anātman, no-self doctrine) which rejects the concepts of a permanent self or an unchanging, eternal soul, as it is called in Hinduism and Christianity. According to Buddhism there ultimately is no such thing as a self in any being or any essence in any thing.

The Buddhist traditions have traditionally disagreed on what it

is in a person that is reborn, as well as how quickly the rebirth occurs

after each death. Some Buddhist traditions assert that "no self" doctrine means that there is no perduring self, but there is avacya (inexpressible) self which migrates from one life to another. The majority of Buddhist traditions, in contrast, assert that vijñāna

(a person's consciousness) though evolving, exists as a continuum and

is the mechanistic basis of what undergoes rebirth, rebecoming and

redeath. The rebirth depends on the merit or demerit gained by one's karma, as well as that accrued on one's behalf by a family member.

Each rebirth takes place within one of five realms according to

Theravadins, or six according to other schools – heavenly, demi-gods,

humans, animals, hungry ghosts and hellish.

In East Asian and Tibetan Buddhism, rebirth is not instantaneous, and there is an intermediate state (Tibetan "bardo") between one life and the next. The orthodox Theravada position rejects the wait, and asserts that rebirth of a being is immediate. However there are passages in the Samyutta Nikaya

of the Pali Canon that seem to lend support to the idea that the Buddha

taught about an intermediate stage between one life and the next.

Karma

In Buddhism, karma (from Sanskrit: "action, work") drives saṃsāra – the endless cycle of suffering and rebirth for each being. Good, skilful deeds (Pāli: kusala) and bad, unskilful deeds (Pāli: akusala) produce "seeds" in the unconscious receptacle (ālaya) that mature later either in this life or in a subsequent rebirth.

The existence of karma is a core belief in Buddhism, as with all major

Indian religions, it implies neither fatalism nor that everything that

happens to a person is caused by karma.

A central aspect of Buddhist theory of karma is that intent (cetanā) matters and is essential to bring about a consequence or phala "fruit" or vipāka "result".

However, good or bad karma accumulates even if there is no physical

action, and just having ill or good thoughts creates karmic seeds; thus,

actions of body, speech or mind all lead to karmic seeds.

In the Buddhist traditions, life aspects affected by the law of karma

in past and current births of a being include the form of rebirth, realm

of rebirth, social class, character and major circumstances of a

lifetime. It operates like the laws of physics, without external intervention, on every being in all six realms of existence including human beings and gods.

A notable aspect of the karma theory in Buddhism is merit transfer.

A person accumulates merit not only through intentions and ethical

living, but also is able to gain merit from others by exchanging goods

and services, such as through dāna (charity to monks or nuns). Further, a person can transfer one's own good karma to living family members and ancestors.

Liberation

Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya, India, where Gautama Buddha attained nirvana under the Bodhi Tree (left)

The cessation of the kleshas and the attainment of nirvana (nibbāna),

with which the cycle of rebirth ends, has been the primary and the

soteriological goal of the Buddhist path for monastic life since the

time of the Buddha. The term "path" is usually taken to mean the Noble Eightfold Path, but other versions of "the path" can also be found in the Nikayas. In some passages in the Pali Canon, a distinction is being made between right knowledge or insight (sammā-ñāṇa), and right liberation or release (sammā-vimutti), as the means to attain cessation and liberation.

Nirvana literally means "blowing out, quenching, becoming extinguished".

In early Buddhist texts, it is the state of restraint and self-control

that leads to the "blowing out" and the ending of the cycles of

sufferings associated with rebirths and redeaths. Many later Buddhist texts describe nirvana as identical with anatta with complete "emptiness, nothingness". In some texts, the state is described with greater detail, such as passing through the gate of emptiness (sunyata) – realizing that there is no soul or self in any living being, then passing through the gate of signlessness (animitta) – realizing that nirvana cannot be perceived, and finally passing through the gate of wishlessness (apranihita) – realizing that nirvana is the state of not even wishing for nirvana.

The nirvana state has been described in Buddhist texts partly in a

manner similar to other Indian religions, as the state of complete

liberation, enlightenment, highest happiness, bliss, fearlessness,

freedom, permanence, non-dependent origination, unfathomable, and

indescribable. It has also been described in part differently, as a state of spiritual release marked by "emptiness" and realization of non-self.

While Buddhism considers the liberation from saṃsāra

as the ultimate spiritual goal, in traditional practice, the primary

focus of a vast majority of lay Buddhists has been to seek and

accumulate merit through good deeds, donations to monks and various

Buddhist rituals in order to gain better rebirths rather than nirvana.

The path to liberation: Bhavana (practice, cultivation)

While the Noble Eightfold Path is best-known in the west, a wide

variety of practices and stages have been used and described in the

Buddhist traditions. Basic practices include sila (ethics), samadhi (meditation, dhyana) and prajna

(wisdom), as described in the Noble Eightfold Path. An important

additional practice is a kind and compassionate attitude toward every

living being and the world. Devotion

is also important in some Buddhist traditions, and in the Tibetan

traditions visualizations of deities and mandalas are important. The

value of textual study is regarded differently in the various Buddhist

traditions. It is central to Theravada and highly important to Tibetan

Buddhism, while the Zen tradition takes an ambiguous stance.

Refuge in the Three Jewels

Relic depicting a footprint of the Buddha with Dharmachakra and Triratna, first century CE, Gandhāra

Traditionally, the first step in most Buddhist schools requires taking Three Refuges, also called the Three Jewels (Sanskrit: triratna, Pali: tiratana) as the foundation of one's religious practice. Pali texts employ the Brahmanical motif of the triple refuge, found in the Rigveda 9.97.47, Rigveda 6.46.9 and Chandogya Upanishad 2.22.3–4. Tibetan Buddhism sometimes adds a fourth refuge, in the lama. The three refuges are believed by Buddhists to be protective and a form of reverence.

The Three Jewels are:

- The Gautama Buddha, the historical Buddha, the Blessed One, the Awakened with true knowledge

- The Dharma, the precepts, the practice, the Four Truths, the Eightfold Path

- The Sangha, order of monks, the community of Buddha's disciples

Reciting the three refuges is considered in Buddhism not as a place

to hide, rather a thought that purifies, uplifts and strengthens.

The Buddhist path

Theravada – Noble Eightfold Path

The Dharmachakra represents the Noble Eightfold Path.

An important guiding principle of Buddhist practice is the Middle Way (madhyamapratipad). It was a part of Buddha's first sermon, where he presented the Noble Eightfold Path that was a 'middle way' between the extremes of asceticism and hedonistic sense pleasures. In Buddhism, states Harvey, the doctrine of "dependent arising" (conditioned arising, pratītyasamutpāda)

to explain rebirth is viewed as the 'middle way' between the doctrines

that a being has a "permanent soul" involved in rebirth (eternalism) and

"death is final and there is no rebirth" (annihilationism).

In the Theravada canon, the Pali-suttas, various often

irreconcilable sequences can be found. According to Carol Anderson, the

Theravada canon lacks "an overriding and comprehensive structure of the

path to nibbana." Nevertheless, the Noble Eightfold Path,

or "Eightfold Path of the Noble Ones", has become an important

description of the Buddhist path. It consists of a set of eight

interconnected factors or conditions, that when developed together, lead

to the cessation of dukkha.

These eight factors are: Right View (or Right Understanding), Right

Intention (or Right Thought), Right Speech, Right Action, Right

Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration.

This Eightfold Path is the fourth of the Four Noble Truths, and asserts the path to the cessation of dukkha (suffering, pain, unsatisfactoriness). The path teaches that the way of the enlightened ones stopped their craving, clinging and karmic accumulations, and thus ended their endless cycles of rebirth and suffering.

The Noble Eightfold Path is grouped into three basic divisions, as follows:

| Division | Eightfold factor | Sanskrit, Pali | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wisdom (Sanskrit: prajñā, Pāli: paññā) |

1. Right view | samyag dṛṣṭi, sammā ditthi |

The belief that there is an afterlife and not everything ends with death, that Buddha taught and followed a successful path to nirvana; according to Peter Harvey, the right view is held in Buddhism as a belief in the Buddhist principles of karma and rebirth, and the importance of the Four Noble Truths and the True Realities. |

| 2. Right intention | samyag saṃkalpa, sammā saṅkappa |

Giving up home and adopting the life of a religious mendicant in order to follow the path; this concept, states Harvey, aims at peaceful renunciation, into an environment of non-sensuality, non-ill-will (to lovingkindness), away from cruelty (to compassion). | |

| Moral virtues (Sanskrit: śīla, Pāli: sīla) |

3. Right speech | samyag vāc, sammā vāca |

No lying, no rude speech, no telling one person what another says about him, speaking that which leads to salvation; |

| 4. Right action | samyag karman, sammā kammanta |

No killing or injuring, no taking what is not given; no sexual acts in monastic pursuit, for lay Buddhists no sensual misconduct such as sexual involvement with someone married, or with an unmarried woman protected by her parents or relatives. | |

| 5. Right livelihood | samyag ājīvana, sammā ājīva |

For monks, beg to feed, only possessing what is essential to sustain life. For lay Buddhists, the canonical texts state right livelihood as abstaining from wrong livelihood, explained as not becoming a source or means of suffering to sentient beings by cheating them, or harming or killing them in any way. | |

| Meditation (Sanskrit and Pāli: samādhi) |

6. Right effort | samyag vyāyāma, sammā vāyāma |

Guard against sensual thoughts; this concept, states Harvey, aims at preventing unwholesome states that disrupt meditation. |

| 7. Right mindfulness | samyag smṛti, sammā sati |

Never be absent minded, conscious of what one is doing; this, states Harvey, encourages mindfulness about impermanence of the body, feelings and mind, as well as to experience the five skandhas, the five hindrances, the four True Realities and seven factors of awakening. | |

| 8. Right concentration | samyag samādhi, sammā samādhi |

Correct meditation or concentration (dhyana), explained as the four jhānas. |

Mahayana – Bodhisattva-path and the six paramitas

Dāna or charitable giving to monks is a virtue in Buddhism, leading to merit accumulation and better rebirths.

Mahāyāna Buddhism is based principally upon the path of a Bodhisattva. A Bodhisattva refers to one who is on the path to buddhahood. The term Mahāyāna was originally a synonym for Bodhisattvayāna or "Bodhisattva Vehicle."

In the earliest texts of Mahayana Buddhism, the path of a bodhisattva was to awaken the bodhicitta. Between the 1st and 3rd century CE, this tradition introduced the Ten Bhumi doctrine, which means ten levels or stages of awakening.

This development was followed by the acceptance that it is impossible

to achieve Buddhahood in one (current) lifetime, and the best goal is

not nirvana for oneself, but Buddhahood after climbing through the ten

levels during multiple rebirths.

Mahayana scholars then outlined an elaborate path, for monks and

laypeople, and the path includes the vow to help teach Buddhist

knowledge to other beings, so as to help them cross samsara and liberate

themselves, once one reaches the Buddhahood in a future rebirth. One part of this path are the Pāramitā (perfections, to cross over), derived from the Jatakas tales of Buddha's numerous rebirths.

The Mahayana texts are inconsistent in their discussion of the Paramitas, and some texts include lists of two, others four, six, ten and fifty-two. The six paramitas have been most studied, and these are:

- Dāna pāramitā: perfection of giving; primarily to monks, nuns and the Buddhist monastic establishment dependent on the alms and gifts of the lay householders, in return for generating religious merit; some texts recommend ritually transferring the merit so accumulated for better rebirth to someone else

- Śīla pāramitā: perfection of morality; it outlines ethical behaviour for both the laity and the Mahayana monastic community; this list is similar to Śīla in the Eightfold Path (i.e. Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood)

- Kṣānti pāramitā: perfection of patience, willingness to endure hardship

- Vīrya pāramitā: perfection of vigour; this is similar to Right Effort in the Eightfold Path

- Dhyāna pāramitā: perfection of meditation; this is similar to Right Concentration in the Eightfold Path

- Prajñā pāramitā: perfection of insight (wisdom), awakening to the characteristics of existence such as karma, rebirths, impermanence, no-self, dependent origination and emptiness; this is complete acceptance of the Buddha teaching, then conviction, followed by ultimate realization that "dharmas are non-arising".

In Mahayana Sutras that include ten Paramitas, the additional four perfections are "skillful means, vow, power and knowledge". The most discussed Paramita and the highest rated perfection in Mahayana texts is the "Prajna-paramita", or the "perfection of insight".

This insight in the Mahayana tradition, states Shōhei Ichimura, has

been the "insight of non-duality or the absence of reality in all

things".

Śīla – Buddhist ethics

Statue of Gautama Buddha, first century CE, Gandhara, present-day Pakistan (Guimet Museum)

Śīla (Sanskrit) or sīla (Pāli) is the concept of "moral virtues", that is the second group and an integral part of the Noble Eightfold Path. It consists of right speech, right action and right livelihood.

Śīla appear as ethical precepts for both lay and ordained

Buddhist devotees. It includes the Five Precepts for laypeople, Eight or

Ten Precepts for monastic life, as well as rules of Dhamma (Vinaya or Patimokkha) adopted by a monastery.

Precepts

Buddhist scriptures explain the five precepts (Pali: pañcasīla; Sanskrit: pañcaśīla) as the minimal standard of Buddhist morality. It is the most important system of morality in Buddhism, together with the monastic rules. The five precepts apply to both male and female devotees, and these are:

- Abstain from killing (Ahimsa);

- Abstain from stealing;

- Abstain from sensual (including sexual) misconduct;

- Abstain from lying;

- Abstain from intoxicants.

Undertaking and upholding the five precepts is based on the principle of non-harming (Pāli and Sanskrit: ahiṃsa). The Pali Canon recommends one to compare oneself with others, and on the basis of that, not to hurt others. Compassion and a belief in karmic retribution form the foundation of the precepts. Undertaking the five precepts is part of regular lay devotional practice, both at home and at the local temple. However, the extent to which people keep them differs per region and time. They are sometimes referred to as the śrāvakayāna precepts in the Mahāyāna tradition, contrasting them with the bodhisattva precepts.

The five precepts are not commandments and transgressions do not

invite religious sanctions, but their power has been based on the

Buddhist belief in karmic consequences and their impact in the

afterlife. Killing in Buddhist belief leads to rebirth in the hell

realms, and for a longer time in more severe conditions if the murder

victim was a monk. Adultery, similarly, invites a rebirth as prostitute

or in hell, depending on whether the partner was unmarried or married.

These moral precepts have been voluntarily self-enforced in lay

Buddhist culture through the associated belief in karma and rebirth. Within the Buddhist doctrine, the precepts are meant to develop mind and character to make progress on the path to enlightenment.

The monastic life in Buddhism has additional precepts as part of patimokkha, and unlike lay people, transgressions by monks do invite sanctions. Full expulsion from sangha

follows any instance of killing, engaging in sexual intercourse, theft

or false claims about one's knowledge. Temporary expulsion follows a

lesser offence. The sanctions vary per monastic fraternity (nikaya).

Lay people and novices in many Buddhist fraternities also uphold eight (asta shila) or ten (das shila) from time to time. Four of these are same as for the lay devotee: no killing, no stealing, no lying, and no intoxicants. The other four precepts are:

- No sexual activity;

- Abstain from eating at the wrong time (e.g. only eat solid food before noon);

- Abstain from jewellery, perfume, adornment, entertainment;

- Abstain from sleeping on high bed i.e. to sleep on a mat on the ground.

All eight precepts are sometimes observed by lay people on uposatha days: full moon, new moon , the first and last quarter following the lunar calendar. The ten precepts also include to abstain from accepting money.

In addition to these precepts, Buddhist monasteries have hundreds of rules of conduct, which are a part of its patimokkha.

Vinaya

Monks performing a ceremony in Hangzhou, China

Vinaya is the specific code of conduct for a sangha of monks or nuns. It includes the Patimokkha,

a set of 227 offences including 75 rules of decorum for monks, along

with penalties for transgression, in the Theravadin tradition. The precise content of the Vinaya Pitaka

(scriptures on the Vinaya) differs in different schools and tradition,

and different monasteries set their own standards on its implementation.

The list of pattimokkha is recited every fortnight in a ritual gathering of all monks.

Buddhist text with vinaya rules for monasteries have been traced in all

Buddhist traditions, with the oldest surviving being the ancient

Chinese translations.

Monastic communities in the Buddhist tradition cut normal social

ties to family and community, and live as "islands unto themselves". Within a monastic fraternity, a sangha has its own rules.

A monk abides by these institutionalized rules, and living life as the

vinaya prescribes it is not merely a means, but very nearly the end in

itself. Transgressions by a monk on Sangha vinaya rules invites enforcement, which can include temporary or permanent expulsion.

Samadhi (dhyana) – meditation

Bhikkhus in Thailand

A wide range of meditation practices has developed in the Buddhist

traditions, but "meditation" primarily refers to the practice of dhyana c.q. jhana.

It is a practice in which the attention of the mind is first narrowed

to the focus on one specific object, such as the breath, a concrete

object, or a specific thought, mental image or mantra. After this

initial focusing of the mind, the focus is coupled to mindfulness,

maintaining a calm mind while being aware of one's surroundings. The practice of dhyana aids in maintaining a calm mind, and avoiding disturbance of this calm mind by mindfulness of disturbing thoughts and feelings.

Origins

The earliest evidence of yogis and their meditative tradition, states Karel Werner, is found in the Keśin hymn 10.136 of the Rigveda. While evidence suggests meditation was practised in the centuries preceding the Buddha,

the meditative methodologies described in the Buddhist texts are some

of the earliest among texts that have survived into the modern era. These methodologies likely incorporate what existed before the Buddha as well as those first developed within Buddhism.

According to Bronkhorst, the Four Dhyanas was a Buddhist invention.

Bronkhorst notes that the Buddhist canon has a mass of contradictory

statements, little is known about their relative chronology, and "there

can be no doubt that the canon – including the older parts, the Sutra

and Vinaya Pitaka – was composed over a long period of time". Meditative practices were incorporated from other sramanic movements;

the Buddhist texts describe how Buddha learnt the practice of the

formless dhyana from Brahmanical practices, in the Nikayas ascribed to

Alara Kalama and Uddaka Ramaputta.

The Buddhist canon also describes and criticizes alternative dhyana

practices, which likely mean the pre-existing mainstream meditation

practices of Jainism and Hinduism.

Buddha added a new focus and interpretation, particularly through the Four Dhyanas methodology, in which mindfulness is maintained. Further, the focus of meditation and the underlying theory of liberation guiding the meditation has been different in Buddhism.

For example, states Bronkhorst, the verse 4.4.23 of the Brihadaranyaka

Upanishad with its "become calm, subdued, quiet, patiently enduring,

concentrated, one sees soul in oneself" is most probably a meditative

state.

The Buddhist discussion of meditation is without the concept of soul

and the discussion criticizes both the ascetic meditation of Jainism and

the "real self, soul" meditation of Hinduism.

Four rupa-jhāna and four arupa-jhāna

Buddhist monuments in the Horyu-ji Area

For Nirvana, Buddhist texts teach various meditation methodologies, of which rupa-jhana (four meditations in the realm of form) and arupa-jhana (four meditations in the formless realm) have been the most studied. These are described in the Pali Canon as trance-like states in the world of desirelessness. The four dhyanas under rupa-jhanas are:

- First dhyana: detach from all sensory desires and sinful states that are a source of unwholesome karma. Success here is described in Buddhist texts as leading to discursive thinking, deliberation, detachment, sukha (pleasure) and priti (rapture).

- Second dhyana: cease deliberation and all discursive thoughts. Success leads to one-pointed thinking, serenity, pleasure and rapture.

- Third dhyana: lose feeling of rapture. Success leads to equanimity, mindfulness and pleasure, without rapture.

- Fourth dhyana: cease all effects, lose all happiness and sadness. Success in the fourth meditation stage leads to pure equanimity and mindfulness, without any pleasure or pain.

The arupa-jhanas (formless realm meditation) are also four, which are entered by those who have mastered the rupa-jhanas (Arhats).

The first formless dhyana gets to infinite space without form or colour

or shape, the second to infinity of perception base of the infinite

space, the third formless dhyana transcends object-subject perception

base, while the fourth is where he dwells in nothing-at-all where there

are no feelings, no ideas, nor are there non-ideas, unto total

cessation. The four rupa-dhyanas in Buddhist practice lead to rebirth in successfully better rupa Brahma heavenly realms, while arupa-dhyanas lead into arupa heavens.

Richard Gombrich notes that the sequence of the four rupa-jhanas

describes two different cognitive states. The first two describe a

narrowing of attention, while in the third and fourth jhana attention is

expanded again. Alexander Wynne further explains that the dhyana-scheme is poorly understood. According to Wynne, words expressing the inculcation of awareness, such as sati, sampajāno, and upekkhā, are mistranslated or understood as particular factors of meditative states, whereas they refer to a particular way of perceiving the sense objects.

Meditation and insight

Statue of the Buddha in meditation position, Haw Phra Kaew, Vientiane, Laos

The Buddhist tradition has incorporated two traditions regarding the use of dhyāna (meditation, Pali jhāna). There is a tradition that stresses attaining prajñā (insight, bodhi, kenshō, vipassana) as the means to awakening and liberation. But it has also incorporated the yogic tradition, as reflected in the use of jhana, which is rejected in other sutras as not resulting in the final result of liberation. Lambert Schmithausen, a professor of Buddhist Studies, discerns three possible roads to liberation as described in the suttas, to which Vetter adds the sole practice of dhyana itself.

According to Vetter and Bronkhorst, the earliest Buddhist path

consisted of a set of practices which culminate in the practice of dhyana, leading to a calm of mind which according to Vetter is the liberation which is being sought. Frauwallner notes that the Buddha regarded tanha,

"thirst," craving, to be the cause of suffering, not ignorance. But

this was in contradiction to the Indian traditions of the time, and

posed a problem, which was then also incorporated into the Buddhis

teachings. Later on, "liberating insight" came to be regarded as equally liberating. This "liberating insight" came to be exemplified by prajna, or the insight in the "four truths," but also by other elements of the Buddhist teachings.

The Brahma-vihara

Statue of Buddha in Wat Phra Si Rattana Mahathat, Phitsanulok, Thailand

The four immeasurables or four abodes, also called Brahma-viharas,

are virtues or directions for meditation in Buddhist traditions, which

helps a person be reborn in the heavenly (Brahma) realm. These are traditionally believed to be a characteristic of the deity Brahma and the heavenly abode he resides in.

The four Brahma-vihara are:

- Loving-kindness (Pāli: mettā, Sanskrit: maitrī) is active good will towards all;

- Compassion (Pāli and Sanskrit: karuṇā) results from metta; it is identifying the suffering of others as one's own;

- Empathetic joy (Pāli and Sanskrit: muditā): is the feeling of joy because others are happy, even if one did not contribute to it; it is a form of sympathetic joy;

- Equanimity (Pāli: upekkhā, Sanskrit: upekṣā): is even-mindedness and serenity, treating everyone impartially.

According to Peter Harvey, the Buddhist scriptures acknowledge that the four Brahmavihara meditation practices "did not originate within the Buddhist tradition".

The Brahmavihara (sometimes as Brahmaloka), along with the tradition of

meditation and the above four immeasurables are found in pre-Buddha and

post-Buddha Vedic and Sramanic literature.

Aspects of the Brahmavihara practice for rebirths into the heavenly

realm have been an important part of Buddhist meditation tradition.

According to Gombrich, the Buddhist usage of the brahma-vihāra

originally referred to an awakened state of mind, and a concrete

attitude toward other beings which was equal to "living with Brahman"

here and now. The later tradition took those descriptions too literally,

linking them to cosmology and understanding them as "living with

Brahman" by rebirth in the Brahma-world. According to Gombrich, "the Buddha taught that kindness – what Christians tend to call love – was a way to salvation."

Visualizations: deities, mandalas

Mandala are used in Buddhism for initiation ceremonies and visualization.

Idols of deity and icons have been a part of the historic practice, and in Buddhist texts such as the 11th-century Sadanamala, a devotee visualizes and identifies himself or herself with the imagined deity as part of meditation.

This has been particularly popular in Vajrayana meditative traditions,

but also found in Mahayana and Theravada traditions, particularly in

temples and with Buddha images.

In Tibetan Buddhism tradition, mandala are mystical maps for the visualization process with cosmic symbolism. There are numerous deities, each with a mandala, and they are used during initiation ceremonies and meditation.

The mandalas are concentric geometric shapes symbolizing layers of the

external world, gates and sacred space. The meditation deity is in the

centre, sometimes surrounded by protective gods and goddesses.

Visualizations with deities and mandalas in Buddhism is a tradition

traceable to ancient times, and likely well established by the time the

5th-century text Visuddhimagga was composed.

Practice: monks, laity

According to Peter Harvey, whenever Buddhism has been healthy, not

only ordained but also more committed lay people have practised formal

meditation.

Loud devotional chanting however, adds Harvey, has been the most

prevalent Buddhist practice and considered a form of meditation that

produces "energy, joy, lovingkindness and calm", purifies mind and

benefits the chanter.

Throughout most of Buddhist history, meditation has been

primarily practised in Buddhist monastic tradition, and historical

evidence suggests that serious meditation by lay people has been an

exception. In recent history, sustained meditation has been pursued by a minority of monks in Buddhist monasteries.

Western interest in meditation has led to a revival where ancient

Buddhist ideas and precepts are adapted to Western mores and interpreted

liberally, presenting Buddhism as a meditation-based form of

spirituality.

Prajñā – insight

Monks debating at Sera Monastery, Tibet

Prajñā (Sanskrit) or paññā (Pāli) is insight or knowledge of the true nature of existence. The Buddhist tradition regards ignorance (avidyā), a fundamental ignorance, misunderstanding or mis-perception of the nature of reality, as one of the basic causes of dukkha and samsara.

By overcoming ignorance or misunderstanding one is enlightened and

liberated. This overcoming includes awakening to impermanence and the

non-self nature of reality, and this develops dispassion for the objects of clinging, and liberates a being from dukkha and saṃsāra. Prajñā

is important in all Buddhist traditions, and is the wisdom about the

dharmas, functioning of karma and rebirths, realms of samsara,

impermanence of everything, no-self in anyone or anything, and dependent

origination.

Origins

The origins of "liberating insight" are unclear. Buddhist texts,

states Bronkhorst, do not describe it explicitly, and the content of

"liberating insight" is likely not original to Buddhism.

According to Vetter and Bronkhorst, this growing importance of

"liberating insight" was a response to other religious groups in India,

which held that a liberating insight was indispensable for moksha, liberation from rebirth.

Bronkhorst suggests that the conception of what exactly

constituted "liberating insight" for Buddhists developed over time.

Whereas originally it may not have been specified as an insight, later

on the Four Noble Truths served as such, to be superseded by pratityasamutpada, and still later, in the Hinayana schools, by the doctrine of the non-existence of a substantial self or person.

Other descriptions of this "liberating insight" exist in the Buddhist canon: that the five Skandhas are impermanent, disagreeable, and neither the Self nor belonging to oneself"; "the contemplation of the arising and disappearance (udayabbaya) of the five Skandhas"; "the realisation of the Skandhas as empty (rittaka), vain (tucchaka) and without any pith or substance (asaraka).

— Lambert Schmithausen

In the Pali Canon liberating insight is attained in the fourth dhyana.

However, states Vetter, modern scholarship on the Pali Canon has

uncovered a "whole series of inconsistencies in the transmission of the

Buddha's word", and there are many conflicting versions of what

constitutes higher knowledge and samadhi that leads to the liberation

from rebirth and suffering.

Even within the Four Dhyana methodology of meditation, Vetter notes

that "penetrating abstract truths and penetrating them successively does

not seem possible in a state of mind which is without contemplation and

reflection." According to Vetter, dhyāna itself constituted the original "liberating practice".

Carol Anderson notes that insight is often depicted in the Vinaya

as the opening of the Dhamma eye, which sets one on the Buddhist path

to liberation.

Theravada

Shwezigon Pagoda near Bagan, Myanmar

Vipassanā

In Theravada Buddhism, but also in Tibetan Buddhism, two types of meditation Buddhist practices are being followed, namely samatha (Pāli; Sanskrit: śamatha; "calm") and vipassana (insight). Samatha is also called "calming meditation", and was adopted into Buddhism from pre-Buddha Indian traditions. Vipassanā

meditation was added by Buddha, and refers to "insight meditation".

Vipassana does not aim at peace and tranquillity, states Damien Keown,

but "the generation of penetrating and critical insight (panna)".

The focus of Vipassana meditation is to continuously and thoroughly know impermanence of everything (annica), no-Self in anything (anatta) and the dukkha teachings of Buddhism.

Contemporary Theravada orthodoxy regards samatha as a preparation

for vipassanā, pacifying the mind and strengthening the concentration

in order to allow the work of insight, which leads to liberation. In

contrast, the Vipassana Movement argues that insight levels can be

discerned without the need for developing samatha further due to the

risks of going out of the course when strong samatha is developed.

Dependent arising

Pratityasamutpada, also called "dependent arising, or

dependent origination", is the Buddhist theory to explain the nature and

relations of being, becoming, existence and ultimate reality. Buddhism

asserts that there is nothing independent, except the state of nirvana.

All physical and mental states depend on and arise from other

pre-existing states, and in turn from them arise other dependent states

while they cease.

The 'dependent arisings' have a causal conditioning, and thus Pratityasamutpada is the Buddhist belief that causality is the basis of ontology, not a creator God nor the ontological Vedic concept called universal Self (Brahman) nor any other 'transcendent creative principle'.

However, the Buddhist thought does not understand causality in terms of

Newtonian mechanics, rather it understands it as conditioned arising.

In Buddhism, dependent arising is referring to conditions created by a

plurality of causes that necessarily co-originate a phenomenon within

and across lifetimes, such as karma in one life creating conditions that

lead to rebirth in one of the realms of existence for another lifetime.

Buddhism applies the dependent arising theory to explain origination of endless cycles of dukkha and rebirth, through its Twelve Nidānas or "twelve links" doctrine. It states that because Avidyā (ignorance) exists Saṃskāras (karmic formations) exists, because Saṃskāras exists therefore Vijñāna (consciousness) exists, and in a similar manner it links Nāmarūpa (sentient body), Ṣaḍāyatana (six senses), Sparśa (sensory stimulation), Vedanā (feeling), Taṇhā (craving), Upādāna (grasping), Bhava (becoming), Jāti (birth), and Jarāmaraṇa (old age, death, sorrow, pain).

By breaking the circuitous links of the Twelve Nidanas, Buddhism

asserts that liberation from these endless cycles of rebirth and dukkha

can be attained.

Mahayana

Emptiness

Śūnyatā, or "emptiness", is a central concept in Nagarjuna's Madhyamaka school, and widely attested in the Prajñāpāramitā sutras. It brings together key Buddhist doctrines, particularly anatta and dependent origination, to refute the metaphysics of Sarvastivada and Sautrāntika (extinct non-Mahayana schools). Not only sentient beings are empty of ātman; all phenomena (dharmas) are without any svabhava

(literally "own-nature" or "self-nature"), and thus without any

underlying essence, and "empty" of being independent; thus the

heterodox theories of svabhava circulating at the time were refuted on

the basis of the doctrines of early Buddhism.

Representation-ony c.q. mind-only

Sarvastivada teachings, which were criticized by Nāgārjuna, were reformulated by scholars such as Vasubandhu and Asanga and were adapted into the Yogachara school. One of the main features of Yogācāra philosophy is the concept of vijñapti-mātra. It is often used interchangeably with the term citta-mātra,

but they have different meanings. The standard translation of both

terms is "consciousness-only" or "mind-only." Several modern researchers

object to this translation, and the accompanying label of "absolute

idealism" or "idealistic monism". A better translation for vijñapti-mātra is representation-only, while an alternative translation for citta (mind, thought) mātra (only, exclusively) has not been proposed.

While the Mādhyamaka school held that asserting the existence or

non-existence of any ultimately real thing was inappropriate, some later

exponents of Yogachara asserted that the mind and only the mind is

ultimately real (a doctrine known as cittamatra). Vasubandhu and Asanga however did not assert that mind was truly existent, or the basis of all reality.

These two schools of thought, in opposition or synthesis, form

the basis of subsequent Mahayana metaphysics in the Indo-Tibetan

tradition.

Buddha-nature

Buddha-nature is a concept found in some 1st-millennium CE Buddhist texts, such as the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras. This concept has been controversial in Buddhism, but has a following in East Asian Buddhism. These Sutras suggest, states Paul Williams, that 'all sentient beings contain a Tathagata' as their 'essence, core inner nature, Self'. The Tathagatagarbha

doctrine, at its earliest probably appeared about the later part of the

3rd century CE, and it contradicts the Anatta doctrine (non-Self) in a

vast majority of Buddhist texts, leading scholars to posit that the Tathagatagarbha Sutras were written to promote Buddhism to non-Buddhists. However, the Buddhist text Ratnagotravibhāga states that the "Self" implied in Tathagatagarbha doctrine is actually "not-Self".

Devotion

Bhatti (devotion) at a Buddhist temple, Tibet. Chanting during Bhatti Puja (devotional worship) is often a part of the Theravada Buddhist tradition.

Devotion is an important part of the practice of most Buddhists. Devotional practices include ritual prayer, prostration, offerings, pilgrimage, and chanting.

In Pure Land Buddhism, devotion to the Buddha Amitabha is the main

practice. In Nichiren Buddhism, devotion to the Lotus Sutra is the main

practice. Bhakti (called Bhatti in Pali) has been a common

practice in Theravada Buddhism, where offerings and group prayers are

made to deities and particularly images of Buddha. According to Karel Werner and other scholars, devotional worship has been a significant practice in Theravada Buddhism, and deep devotion is part of Buddhist traditions starting from the earliest days.

Guru devotion is a central practice of Tibetan Buddhism.

The guru is considered essential and to the Buddhist devotee, the guru

is the "enlightened teacher and ritual master" in Vajrayana spiritual

pursuits.

For someone seeking Buddhahood, the guru is the Buddha, the

Dhamma and the Sangha, wrote the 12th-century Buddhist scholar

Sadhanamala. The veneration of and obedience to teachers is also important in Theravada and Zen Buddhism.

Buddhist texts

Buddhist monk Geshe Konchog Wangdu reads Mahayana sutras from an old woodblock copy of the Tibetan Kanjur.

Buddhism, like all Indian religions, was an oral tradition in ancient times.

The Buddha's words, the early doctrines and concepts, and the

interpretations were transmitted from one generation to the next by the

word of mouth in monasteries, and not through written texts. The first

Buddhist canonical texts were likely written down in Sri Lanka, about

400 years after the Buddha died. The texts were part of the Tripitakas,

and many versions appeared thereafter claiming to be the words of the

Buddha. Scholarly Buddhist commentary texts, with named authors,

appeared in India, around the 2nd century CE. These texts were written in Pali or Sanskrit, sometimes regional languages, as palm-leaf manuscripts, birch bark, painted scrolls, carved into temple walls, and later on paper.

Unlike what the Bible is to Christianity and the Quran is to Islam,

but like all major ancient Indian religions, there is no consensus

among the different Buddhist traditions as to what constitutes the

scriptures or a common canon in Buddhism. The general belief among Buddhists is that the canonical corpus is vast. This corpus includes the ancient Sutras organized into Nikayas, itself the part of three basket of texts called the Tripitakas.

Each Buddhist tradition has its own collection of texts, much of which

is translation of ancient Pali and Sanskrit Buddhist texts of India. The

Chinese Buddhist canon, for example, includes 2184 texts in 55 volumes,

while the Tibetan canon comprises 1108 texts—all claimed to have been

spoken by the Buddha—and another 3461 texts composed by Indian scholars

revered in the Tibetan tradition.

The Buddhist textual history is vast; over 40,000 manuscripts—mostly

Buddhist, some non-Buddhist—were discovered in 1900 in the Dunhuang

Chinese cave alone.

Pāli Tipitaka

The Pāli Tipitaka (Sanskrit: Tripiṭaka, three pitakas), which means "three baskets", refers to the Vinaya Pitaka, the Sutta Pitaka, and the Abhidhamma Pitaka. These constitute the oldest known canonical works of Buddhism. The Vinaya Pitaka contains disciplinary rules for the Buddhist monasteries. The Sutta Pitaka contains words attributed to the Buddha. The Abhidhamma Pitaka contain expositions and commentaries on the Sutta, and these vary significantly between Buddhist schools.

The Pāli Tipitaka is the only surviving early Tipitaka. According

to some sources, some early schools of Buddhism had five or seven

pitakas.

Much of the material in the Canon is not specifically "Theravadin", but

is instead the collection of teachings that this school preserved from

the early, non-sectarian body of teachings. According to Peter Harvey,

it contains material at odds with later Theravadin orthodoxy. He states:

"The Theravadins, then, may have added texts to the Canon for some time, but they do not appear to have tampered with what they already had from an earlier period."

Theravada texts

In addition to the Pali Canon, the important commentary texts of the Theravada tradition include the 5th-century Visuddhimagga by Buddhaghosa

of the Mahavihara school. It includes sections on shila (virtues),

samadhi (concentration), panna (wisdom) as well as Theravada tradition's

meditation methodology.

Mahayana sutras

The Tripiṭaka Koreana in South Korea, an edition of the Chinese Buddhist canon carved and preserved in over 81,000 wood printing blocks

The Mahayana sutras are a very broad genre of Buddhist scriptures that the Mahayana Buddhist tradition holds are original teachings of the Buddha.

Some adherents of Mahayana accept both the early teachings (including

in this the Sarvastivada Abhidharma, which was criticized by Nagarjuna

and is in fact opposed to early Buddhist thought)

and the Mahayana sutras as authentic teachings of Gautama Buddha, and

claim they were designed for different types of persons and different

levels of spiritual understanding.

The Mahayana sutras often claim to articulate the Buddha's deeper, more advanced doctrines, reserved for those who follow the bodhisattva path. That path is explained as being built upon the motivation to liberate all living beings from unhappiness. Hence the name Mahāyāna (lit., the Great Vehicle). The Theravada school does not treat the Mahayana Sutras as authoritative or authentic teachings of the Buddha.

Generally, scholars conclude that the Mahayana scriptures were

composed from the 1st century CE onwards: "Large numbers of Mahayana

sutras were being composed in the period between the beginning of the

common era and the fifth century".

Śālistamba Sutra

Many ancient Indian texts have not survived into the modern era,

creating a challenge in establishing the historic commonalities between

Theravada and Mahayana. The texts preserved in the Tibetan Buddhist

monasteries, with parallel Chinese translations, have provided a

breakthrough. Among these is the Mahayana text Śālistamba Sutra

which no longer exists in a Sanskrit version, but does in Tibetan and

Chinese versions. This Mahayana text contains numerous sections which

are remarkably the same as the Theravada Pali Canon and Nikaya Buddhism. The Śālistamba Sutra was cited by Mahayana scholars such as the 8th-century Yasomitra to be authoritative.

This suggests that Buddhist literature of different traditions shared a

common core of Buddhist texts in the early centuries of its history,

until Mahayana literature diverged about and after the 1st century CE.

History

Historical roots

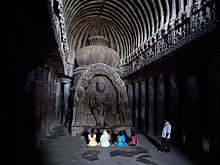

The Buddhist "Carpenter's Cave" at Ellora in Maharashtra, India

Historically, the roots of Buddhism lie in the religious thought of Iron Age India around the middle of the first millennium BCE. This was a period of great intellectual ferment and socio-cultural change known as the "Second urbanisation", marked by the composition of the Upanishads and the historical emergence of the Sramanic traditions.

New ideas developed both in the Vedic tradition in the form of the Upanishads, and outside of the Vedic tradition through the Śramaṇa movements. The term Śramaṇa refers to several Indian religious movements parallel to but separate from the historical Vedic religion, including Buddhism, Jainism and others such as Ājīvika.

Several Śramaṇa movements are known to have existed in India before the 6th century BCE (pre-Buddha, pre-Mahavira), and these influenced both the āstika and nāstika traditions of Indian philosophy. According to Martin Wilshire, the Śramaṇa tradition evolved in India over two phases, namely Paccekabuddha and Savaka phases, the former being the tradition of individual ascetic and the latter of disciples, and that Buddhism and Jainism ultimately emerged from these. Brahmanical and non-Brahmanical ascetic groups shared and used several similar ideas,

but the Śramaṇa traditions also drew upon already established

Brahmanical concepts and philosophical roots, states Wiltshire, to

formulate their own doctrines. Brahmanical motifs can be found in the oldest Buddhist texts, using them to introduce and explain Buddhist ideas. For example, prior to Buddhist developments, the Brahmanical tradition internalized and variously reinterpreted the three Vedic sacrificial fires as concepts such as Truth, Rite, Tranquility or Restraint. Buddhist texts also refer to the three Vedic sacrificial fires, reinterpreting and explaining them as ethical conduct.

The Śramaṇa religions challenged and broke with the Brahmanic tradition on core assumptions such as Atman (soul, self), Brahman, the nature of afterlife, and they rejected the authority of the Vedas and Upanishads. Buddhism was one among several Indian religions that did so.

Rock-cut Lord Buddha statue at Bojjanakonda near Anakapalle in the Visakhapatnam district of Andhra Pradesh, India

Indian Buddhism

The history of Indian Buddhism may be divided into five periods: Early Buddhism (occasionally called pre-sectarian Buddhism), Nikaya Buddhism or Sectarian Buddhism: The period of the early Buddhist schools, Early Mahayana Buddhism, later Mahayana Buddhism, and Vajrayana Buddhism.

Sanchi Stupa

Pre-sectarian Buddhism

According to Lambert Schmithausen Pre-sectarian Buddhism is "the canonical period prior to the development of different schools with their different positions."

The early Buddhist Texts include the four principal Nikāyas (and their parallel Agamas) together with the main body of monastic rules, which survive in the various versions of the patimokkha.

However, these texts were revised over time, and it is unclear what

constitutes the earliest layer of Buddhist teachings. One method to

obtain information on the oldest core of Buddhism is to compare the

oldest extant versions of the Theravadin Pāli Canon and other texts. The reliability of the early sources, and the possibility to draw out a core of oldest teachings, is a matter of dispute. According to Vetter, inconsistencies remain, and other methods must be applied to resolve those inconsistencies.

According to Schmithausen, three positions held by scholars of Buddhism can be distinguished:

- "Stress on the fundamental homogeneity and substantial authenticity of at least a considerable part of the Nikayic materials;"

- "Scepticism with regard to the possibility of retrieving the doctrine of earliest Buddhism;"

- "Cautious optimism in this respect."

Core teachings

Buddhist Chakras at ASI Museum, Amaravathi

According to Mitchell, certain basic teachings appear in many places

throughout the early texts, which has led most scholars to conclude that

Gautama Buddha must have taught something similar to the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Eightfold Path, Nirvana, the three marks of existence, the five aggregates, dependent origination, karma and rebirth. Yet critical analysis reveals discrepancies, which point to alternative possibilities.

Bruce Matthews notes that there is no cohesive presentation of karma in the Sutta Pitaka, which may mean that the doctrine was incidental to the main perspective of early Buddhist soteriology. Schmithausen has questioned whether karma already played a role in the theory of rebirth of earliest Buddhism. According to Vetter, "the Buddha at first sought "the deathless" (amata/amrta), which is concerned with the here and now. Only later did he become acquainted with the doctrine of rebirth." Bronkhorst

disagrees, and concludes that the Buddha "introduced a concept of karma

that differed considerably from the commonly held views of his time."

According to Bronkhorst, not physical and mental activities as such

were seen as responsible for rebirth, but intentions and desire.

Another core problem in the study of early Buddhism is the relation between dhyana and insight.

Schmithausen states that the four noble truths as "liberating insight",

may be a later addition to texts such as Majjhima Nikaya 36.

According to both Bronkhorst and Anderson, the Four Noble Truths became a substitution for prajna, or "liberating insight", in the suttas in those texts where "liberating insight" was preceded by the four jhānas.

The four truths may not have been formulated in earliest Buddhism, and

did not serve in earliest Buddhism as a description of "liberating

insight". Gotama's teachings may have been personal, "adjusted to the need of each person."

The three marks of existence – Dukkha, Annica, Anatta – may reflect Upanishadic or other influences. K.R. Norman supposes that these terms were already in use at the Buddha's time, and were familiar to his hearers. According to Vetter, the description of the Buddhist path may initially have been as simple as the term "the middle way". In time, this short description was elaborated, resulting in the description of the eightfold path.

Similarly nibbāna is the common term for the desired goal of this

practice, yet many other terms can be found throughout the Nikāyas,

which are not specified.

Early Buddhist schools

Buddha at Xumishan Grottoes, ca. 6th century CE

According to the scriptures, soon after the parinirvāṇa (from Sanskrit: "highest extinguishment") of Gautama Buddha, the first Buddhist council

was held. As with any ancient Indian tradition, transmission of

teaching was done orally. The primary purpose of the assembly was to

collectively recite the teachings to ensure that no errors occurred in

oral transmission. Richard Gombrich

states that the monastic assembly recitations of the Buddha's teaching

likely began during Buddha's lifetime, similar to the First Council,

that helped compose Buddhist scriptures.

The Second Buddhist council resulted in the first schism in the Sangha, probably caused by a group of reformists called Sthaviras who split from the conservative majority Mahāsāṃghikas. After unsuccessfully trying to modify the Vinaya, a small group of "elderly members", i.e. sthaviras, broke away from the majority Mahāsāṃghika during the Second Buddhist council, giving rise to the Sthavira Nikaya.

The Sthaviras gave rise to several schools, one of which was the Theravada

school. Originally, these schisms were caused by disputes over monastic

disciplinary codes of various fraternities, but eventually, by about

100 CE if not earlier, schisms were being caused by doctrinal

disagreements too.

Buddhist monks of different fraternities became distinct schools and

stopped doing official Sangha business together, but continued to study

each other's doctrines.

Following (or leading up to) the schisms, each Saṅgha started to accumulate their own version of Tripiṭaka (Pali Canons, triple basket of texts). In their Tripiṭaka, each school included the Suttas of the Buddha, a Vinaya basket (disciplinary code) and added an Abhidharma basket which were texts on detailed scholastic classification, summary and interpretation of the Suttas.

The doctrine details in the Abhidharmas of various Buddhist schools

differ significantly, and these were composed starting about the third

century BCE and through the 1st millennium CE.

Eighteen early Buddhist schools are known, each with its own Tripitaka,

but only one collection from Sri Lanka has survived, in a nearly

complete state, into the modern era.

Early Mahayana Buddhism

A Buddhist triad depicting, left to right, a Kushan, the future buddha Maitreya, Gautama Buddha, the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara, and a monk. Second–third century. Guimet Museum

Several scholars have suggested that the Mahayana Buddhist tradition started in south India (modern Andhra Pradesh), and it is there that Prajnaparamita sutras, among the earliest Mahayana sutras, developed among the Mahāsāṃghika along the Kṛṣṇa River region about the 1st century BCE.

There is no evidence that Mahayana ever referred to a separate

formal school or sect of Buddhism, but rather that it existed as a

certain set of ideals, and later doctrines, for bodhisattvas. Initially it was known as Bodhisattvayāna (the "Vehicle of the Bodhisattvas"). Paul Williams states that the Mahāyāna never had nor ever attempted to have a separate Vinaya or ordination codes from the early schools of Buddhism.

Records written by Chinese monks visiting India indicate that both

Mahāyāna and non-Mahāyāna monks could be found in the same monasteries,

with the difference that Mahayana monks worshipped figures of

Bodhisattvas, while non-Mahayana monks did not.

Much of the early extant evidence for the origins of Mahāyāna

comes from early Chinese translations of Mahāyāna texts. These Mahayana

teachings were first propagated into China by Lokakṣema, the first translator of Mahayana sutras into Chinese during the 2nd century CE. Some scholars have traditionally considered the earliest Mahāyāna sūtras to include the very first versions of the Prajnaparamita series, along with texts concerning Akṣobhya, which were probably composed in the 1st century BCE in the south of India.

Late Mahayana Buddhism

During the period of Late Mahāyāna, four major types of thought developed: Madhyamaka, Yogachara, Tathagatagarbha, and Buddhist logic as the last and most recent. In India, the two main philosophical schools of the Mahayana were the Madhyamaka and the later Yogachara. According to Dan Lusthaus, Madhyamaka and Yogachara have a great deal in common, and the commonality stems from early Buddhism. There were no great Indian teachers associated with tathagatagarbha thought.

Vajrayana (Esoteric Buddhism)

Scholarly research concerning Esoteric Buddhism is still in its early stages and has a number of problems that make research difficult:

- Vajrayana Buddhism was influenced by Hinduism, and therefore research must include exploring Hinduism as well.

- The scriptures of Vajrayana have not yet been put in any kind of order.

- Ritual must be examined as well, not just doctrine.

Spread of Buddhism

The spread of Buddhism within South Asia and beyond.

Buddhism may have spread only slowly in India until the time of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka, who was a public supporter of the religion. The support of Aśoka and his descendants led to the construction of more stūpas (Buddhist religious memorials) and to its spread throughout the Maurya empire and into neighbouring lands such as Central Asia and to the island of Sri Lanka.

These two missions, in opposite directions, would ultimately lead, in

the first case to the spread of Buddhism into China, Korea and Japan,

and in the second case, to the emergence of Sinhalese Theravāda Buddhism and its spread from Sri Lanka to much of Southeast Asia.

This period marks the first known spread of Buddhism beyond India. According to the edicts of Aśoka,

emissaries were sent to various countries west of India to spread

Buddhism (Dharma), particularly in eastern provinces of the neighbouring

Seleucid Empire, and even farther to Hellenistic

kingdoms of the Mediterranean. It is a matter of disagreement among

scholars whether or not these emissaries were accompanied by Buddhist

missionaries.

Coin depicting Indo-Greek king Menander, who, according to Buddhist tradition records in the Milinda Panha, converted to the Buddhist faith and became an arhat in the 2nd century BCE (British Museum)

In central and west Asia, Buddhist influence grew, through

Greek-speaking Buddhist monarchs and ancient Asian trade routes. An

example of this is evidenced in Chinese and Pali Buddhist records, such

as Milindapanha and the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhāra. The Milindapanha describes a conversation between a Buddhist monk and the 2nd-century BCE Greek king Menander, after which Menander abdicates and himself goes into monastic life in the pursuit of nirvana. Some scholars have questioned the Milindapanha version, expressing doubts whether Menander was Buddhist or just favourably disposed to Buddhist monks.

The Kushans

(mid 1st–3rd century CE) came to control the Silk Road trade through

Central and South Asia, which brought them to interact with ancient

Buddhist monasteries and societies involved in trade in these regions.

They patronized Buddhist institutions, and Buddhist monastery influence,

in turn, expanded into a world religion, according to Xinru Liu. Buddhism spread to Khotan and China, eventually to other parts of the far east.

Some of the earliest written documents of the Buddhist faith are the Gandharan Buddhist texts, dating from about the 1st century CE, and connected to the Dharmaguptaka school. These texts are written in the Kharosthi script, a script that was predominantly used in the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms of northern India and that played a prominent role in the coinage and inscriptions of their kings.

The Islamic conquest of the Iranian Plateau in the 7th-century, followed by the Muslim conquests of Afghanistan and the later establishment of the Ghaznavid kingdom

with Islam as the state religion in Central Asia between the 10th- and

12th-century led to the decline and disappearance of Buddhism from most

of these regions.

To East and Southeast Asia

White Horse Temple (est. 68 CE), traditionally held to be at the origin of Chinese Buddhism.

Angkor Thom build by Khmer King Jayavarman VII (c. 1120–1218).

The Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

to China is most commonly thought to have started in the late 2nd or

the 1st century CE, though the literary sources are all open to

question. The first documented translation efforts by foreign Buddhist monks in China were in the 2nd century CE, probably as a consequence of the expansion of the Kushan Empire into the Chinese territory of the Tarim Basin.

The first documented Buddhist texts translated into Chinese are those of the Parthian An Shigao (148–180 CE). The first known Mahāyāna scriptural texts are translations into Chinese by the Kushan monk Lokakṣema in Luoyang, between 178 and 189 CE. From China, Buddhism was introduced into its neighbors Korea (4th century), Japan (6th–7th centuries), and Vietnam (c. 1st–2nd centuries).

During the Chinese Tang dynasty (618–907), Chinese Esoteric Buddhism was introduced from India and Chan Buddhism (Zen) became a major religion. Chan continued to grow in the Song dynasty (960–1279) and it was during this era that it strongly influenced Korean Buddhism and Japanese Buddhism. Pure Land Buddhism also became popular during this period and was often practiced together with Chan. It was also during the Song that the entire Chinese canon was printed using over 130,000 wooden printing blocks.

During the Indian period of Esoteric Buddhism (from the 8th century onwards), Buddhism spread from India to Tibet and Mongolia.

Johannes Bronkhorst states that the esoteric form was attractive

because it allowed both a secluded monastic community as well as the

social rites and rituals important to laypersons and to kings for the

maintenance of a political state during succession and wars to resist

invasion. During the Middle Ages, Buddhism slowly declined in India, while it vanished from Persia and Central Asia as Islam became the state religion.

The Theravada school arrived in Sri Lanka sometime in the 3rd century BCE. Sri Lanka became a base for its later spread to southeast Asia after the 5th century CE (Myanmar, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia and coastal Vietnam). Theravada Buddhism was the dominant religion in Burma during the Mon Hanthawaddy Kingdom (1287–1552). It also became dominant in the Khmer Empire during the 13th and 14th centuries and in the Thai Sukhothai Kingdom during the reign of Ram Khamhaeng (1237/1247–1298).

Schools and traditions

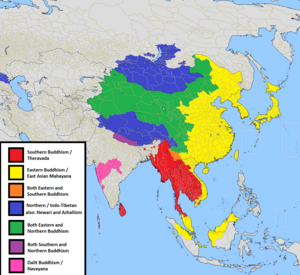

Distribution of major Buddhist traditions

Buddhists generally classify themselves as either Theravada or Mahayana. This classification is also used by some scholars and is the one ordinarily used in the English language. An alternative scheme used by some scholars divides Buddhism into the following three traditions or geographical or cultural areas: Theravada, East Asian Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism.

Young monks in Cambodia

Some scholars use other schemes. Buddhists themselves have a variety of other schemes. Hinayana

(literally "lesser or inferior vehicle") is used by Mahayana followers

to name the family of early philosophical schools and traditions from

which contemporary Theravada emerged, but as the Hinayana term is

considered derogatory, a variety of other terms are used instead,

including Śrāvakayāna, Nikaya Buddhism, early Buddhist schools, sectarian Buddhism and conservative Buddhism.

Not all traditions of Buddhism share the same philosophical

outlook, or treat the same concepts as central. Each tradition, however,

does have its own core concepts, and some comparisons can be drawn

between them:

- Both Theravada and Mahayana traditions accept the Buddha as the founder, Theravada considers him unique, but Mahayana considers him one of many Buddhas

- Both accept the Middle Way, dependent origination, the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Eightfold Path and the three marks of existence

- Nirvana is attainable by the monks in Theravada tradition, while Mahayana considers it broadly attainable; Arhat state is aimed for in the Theravada, while Buddhahood is aimed for in the Mahayana

- Religious practice consists of meditation for monks and prayer for laypersons in Theravada, while Mahayana includes prayer, chanting and meditation for both

- Theravada has been a more rationalist, historical form of Buddhism; while Mahayana has included more rituals, mysticism and worldly flexibility in its scope.

Theravada school

The Theravada tradition traces its roots to the words of the Buddha

preserved in the Pali Canon, and considers itself to be the more

orthodox form of Buddhism.

Theravada flourished in south India and Sri Lanka in ancient

times; from there it spread for the first time into mainland southeast

Asia about the 11th century into its elite urban centres. By the 13th century, Theravada had spread widely into the rural areas of mainland southeast Asia,

displacing Mahayana Buddhism and some traditions of Hinduism which had

arrived in places such as Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia and

Malaysia around the mid-1st millennium CE. The later traditions were

well established in south Thailand and Java by the 7th century, under

the sponsorship of the Srivijaya dynasty.

The political separation between Khmer and Sukhothai led the Sukhothai

king to welcome Sri Lankan emissaries, helping them establish the first

Theravada Buddhist sangha in the 13th century, in contrast to the Mahayana tradition of Khmer earlier.

Sinhalese Buddhist reformers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries portrayed the Pali Canon as the original version of scripture. They also emphasized Theravada being rational and scientific.

Theravāda is primarily practised today in Sri Lanka, Burma, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia as well as small portions of China, Vietnam, Malaysia and Bangladesh. It has a growing presence in the west.

Mahayana traditions

The ideas of the 2nd century scholar Nagarjuna helped shape the Mahayana traditions.

Mahayana schools consider the Mahayana Sutras as authoritative scriptures and accurate rendering of Buddha's words. These traditions have been the more liberal form of Buddhism allowing different and new interpretations that emerged over time.

Mahayana flourished in India from the time of Ashoka, through to the dynasty of the Guptas

(4th to 6th-century). Mahāyāna monastic foundations and centres of

learning were established by the Buddhist kings, and the Hindu kings of

the Gupta dynasty as evidenced by records left by three Chinese visitors

to India. The Gupta dynasty, for example, helped establish the famed Nālandā University in Bihar.

These monasteries and foundations helped Buddhist scholarship, as well

as studies into non-Buddhist traditions and secular subjects such as

medicine, host visitors and spread Buddhism into East and Central Asia.

Native Mahayana Buddhism is practised today in China, Japan, Korea, Singapore, parts of Russia and most of Vietnam

(also commonly referred to as "Eastern Buddhism"). The Buddhism