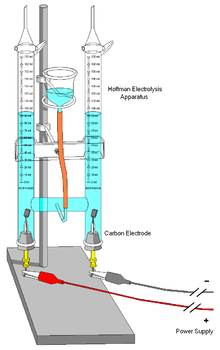

Illustration of an electrolysis apparatus used in a school laboratory

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis is a technique that uses a direct electric current (DC) to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction. Electrolysis is commercially important as a stage in the separation of elements from naturally occurring sources such as ores using an electrolytic cell. The voltage that is needed for electrolysis to occur is called the decomposition potential.

History

The word "electrolysis" was introduced by Michael Faraday in the 19th century, on the suggestion of the Rev. William Whewell, using the Greek words ἤλεκτρον [ɛ̌ːlektron] "amber", which since the 17th century was associated with electric phenomena, and λύσις [lýsis] meaning "dissolution". Nevertheless, electrolysis, as a tool to study chemical reactions and obtain pure elements, precedes the coinage of the term and formal description by Faraday.

- 1785 – Martinus van Marum's electrostatic generator was used to reduce tin, zinc, and antimony from their salts using electrolysis.

- 1800 – William Nicholson and Anthony Carlisle (view also Johann Ritter), decomposed water into hydrogen and oxygen.

- 1808 – Potassium (1807), sodium (1807), barium, calcium and magnesium were discovered by Sir Humphry Davy using electrolysis.

- 1821 – Lithium was discovered by the English chemist William Thomas Brande, who obtained it by electrolysis of lithium oxide.

- 1833 – Michael Faraday develops his two laws of electrolysis, and provides a mathematical explanation of his laws.

- 1875 – Paul Émile Lecoq de Boisbaudran discovered gallium using electrolysis.

- 1886 – Fluorine was discovered by Henri Moissan using electrolysis.

- 1886 – Hall–Héroult process developed for making aluminium

- 1890 – Castner–Kellner process developed for making sodium hydroxide

Overview

Electrolysis is the passing of a direct electric current through an ionic

substance that is either molten or dissolved in a suitable solvent,

producing chemical reactions at the electrodes and a decomposition of

the materials.

The main components required to achieve electrolysis are:

- An electrolyte: a substance, frequently an ion-conducting polymer that contains free ions, which carry electric current in the electrolyte. If the ions are not mobile, as in most solid salts, then electrolysis cannot occur.

- A direct current (DC) electrical supply: provides the energy necessary to create or discharge the ions in the electrolyte. Electric current is carried by electrons in the external circuit.

- Two electrodes: electrical conductors that provide the physical interface between the electrolyte and the electrical circuit that provides the energy.

Electrodes of metal, graphite and semiconductor

material are widely used. Choice of suitable electrode depends on

chemical reactivity between the electrode and electrolyte and

manufacturing cost.

Process of electrolysis

The

key process of electrolysis is the interchange of atoms and ions by the

removal or addition of electrons from the external circuit. The desired

products of electrolysis are often in a different physical state from

the electrolyte and can be removed by some physical processes. For

example, in the electrolysis of brine

to produce hydrogen and chlorine, the products are gaseous. These

gaseous products bubble from the electrolyte and are collected.

- 2 NaCl + 2 H2O → 2 NaOH + H2 + Cl2

A liquid containing electrolyte is produced by:

- Solvation or reaction of an ionic compound with a solvent (such as water) to produce mobile ions

- An ionic compound is melted by heating

An electrical potential is applied across a pair of electrodes immersed in the electrolyte.

Each electrode attracts ions that are of the opposite charge. Positively charged ions (cations) move towards the electron-providing (negative) cathode. Negatively charged ions (anions) move towards the electron-extracting (positive) anode.

In this process electrons

are either absorbed or released. Neutral atoms gain or lose electrons

and become charged ions that then pass into the electrolyte. The

formation of uncharged atoms from ions is called discharging. When an

ion gains or loses enough electrons to become uncharged (neutral) atoms,

the newly formed atoms separate from the electrolyte. Positive metal

ions like Cu2+deposit onto the cathode in a layer. The terms for this are electroplating, electrowinning, and electrorefining.

When an ion gains or loses electrons without becoming neutral, its

electronic charge is altered in the process. In chemistry, the loss of

electrons is called oxidation, while electron gain is called reduction.

Oxidation and reduction at the electrodes

Oxidation of ions or neutral molecules occurs at the anode. For example, it is possible to oxidize ferrous ions to ferric ions at the anode:

- Fe2+(aq) → Fe3+(aq) + e−

It is possible to reduce ferricyanide ions to ferrocyanide ions at the cathode:

- Fe(CN)3-

6 + e− → Fe(CN)4-

6

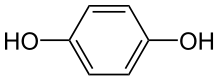

Neutral molecules can also react at either of the electrodes. For

example: p-Benzoquinone can be reduced to hydroquinone at the cathode:

In the last example, H+ ions (hydrogen ions) also take

part in the reaction, and are provided by an acid in the solution, or

by the solvent itself (water, methanol etc.). Electrolysis reactions

involving H+ ions are fairly common in acidic solutions. In aqueous alkaline solutions, reactions involving OH− (hydroxide ions) are common.

Sometimes the solvents themselves (usually water) are oxidized or

reduced at the electrodes. It is even possible to have electrolysis

involving gases. Such as when using a Gas diffusion electrode.

Energy changes during electrolysis

The amount of electrical energy that must be added equals the change in Gibbs free energy of the reaction plus the losses in the system. The losses can (in theory) be arbitrarily close to zero, so the maximum thermodynamic efficiency equals the enthalpy

change divided by the free energy change of the reaction. In most

cases, the electric input is larger than the enthalpy change of the

reaction, so some energy is released in the form of heat. In some cases,

for instance, in the electrolysis of steam

into hydrogen and oxygen at high temperature, the opposite is true and

heat energy is absorbed. This heat is absorbed from the surroundings,

and the heating value of the produced hydrogen is higher than the electric input.

Related techniques

The following techniques are related to electrolysis:

- Electrochemical cells, including the hydrogen fuel cell, use differences in Standard electrode potential to generate an electrical potential that provides useful power. Though related via the interaction of ions and electrolysis and the operation of electrochemical cells are quite distinct. However, a chemical cell should not be seen as performing electrolysis in reverse.

Faraday's laws of electrolysis

First law of electrolysis

In

1832, Michael Faraday reported that the quantity of elements separated

by passing an electric current through a molten or dissolved salt

is proportional to the quantity of electric charge passed through the

circuit. This became the basis of the first law of electrolysis. The

mass of the substance (m) deposited or liberated at any electrode is

directly proportional to the quantity of electricity or charge (Q)

passed. In this equation k is equal to the electromechanical constant.

or

where;

e is known as electrochemical equivalent of the metal deposited or of the gas liberated at the electrode.

Second law of electrolysis

Faraday

discovered that when the same amount of current is passed through

different electrolytes/elements connected in series, the mass of

substance liberated/deposited at the electrodes is directly

proportional to their equivalent weight.

Industrial uses

Hall-Heroult process for producing aluminium

- Electrometallurgy is the process of reduction of metals from metallic compounds to obtain the pure form of metal using electrolysis. Aluminium, lithium, sodium, potassium, magnesium, calcium, and in some cases copper, are produced in this way.

- Production of chlorine and sodium hydroxide

- Production of sodium chlorate and potassium chlorate

- Production of perfluorinated organic compounds such as trifluoroacetic acid by the process of electrofluorination

- Production of electrolytic copper as a cathode, from refined copper of lower purity as an anode.

Electrolysis has many other uses:

- Production of oxygen for spacecraft and nuclear submarines.

- Production of hydrogen for fuel, using a cheap source of electrical energy.

Electrolysis is also used in the cleaning and preservation of old

artifacts. Because the process separates the non-metallic particles from

the metallic ones, it is very useful for cleaning a wide variety of

metallic objects, from old coins to even larger objects including rusted cast iron cylinder blocks and heads when rebuilding automobile engines. Rust removal

from small iron or steel objects by electrolysis can be done in a home

workshop using simple materials such as a plastic bucket, tap water, lengths of rebar, washing soda, baling wire, and a battery charger.

Manufacturing processes

In manufacturing, electrolysis can be used for:

- Electroplating, where a thin film of metal is deposited over a substrate material. Electroplating is used in many industries for either functional or decorative purposes, as in vehicle bodies and nickel coins.

- Electrochemical machining (ECM), where an electrolytic cathode is used as a shaped tool for removing material by anodic oxidation from a workpiece. ECM is often used as technique for deburring or for etching metal surfaces like tools or knives with a permanent mark or logo.

Competing half-reactions in solution electrolysis

Using

a cell containing inert platinum electrodes, electrolysis of aqueous

solutions of some salts leads to reduction of the cations (e.g., metal

deposition with, e.g., zinc salts) and oxidation of the anions (e.g.

evolution of bromine with bromides). However, with salts of some metals

(e.g. sodium) hydrogen is evolved at the cathode, and for salts

containing some anions (e.g. sulfate SO42−) oxygen is evolved at the anode. In both cases this is due to water being reduced to form hydrogen or oxidized to form oxygen.

In principle the voltage required to electrolyze a salt solution can be derived from the standard electrode potential for the reactions at the anode and cathode. The standard electrode potential is directly related to the Gibbs free energy, ΔG, for the reactions at each electrode and refers to an electrode with no current flowing.

In terms of electrolysis, this should be interpreted as follows:

- Oxidized species (often a cation) with a more negative cell potential are more difficult to reduce than oxidized species with a more positive cell potential. For example, it is more difficult to reduce a sodium ion to a sodium metal than it is to reduce a zinc ion to a zinc metal.

- Reduced species (often an anion) with a more positive cell potential are more difficult to oxidize than reduced species with a more negative cell potential. For example, it is more difficult to oxidize sulfate anions than it is to oxidize bromide anions.

Using the Nernst equation the electrode potential can be calculated for a specific concentration of ions, temperature and the number of electrons involved. For pure water (pH 7):

- the electrode potential for the reduction producing hydrogen is −0.41 V

- the electrode potential for the oxidation producing oxygen is +0.82 V.

Comparable figures calculated in a similar way, for 1M zinc bromide, ZnBr2,

are −0.76 V for the reduction to Zn metal and +1.10 V for the oxidation

producing bromine.

The conclusion from these figures is that hydrogen should be produced at

the cathode and oxygen at the anode from the electrolysis of

water—which is at variance with the experimental observation that zinc

metal is deposited and bromine is produced.

The explanation is that these calculated potentials only indicate the

thermodynamically preferred reaction. In practice many other factors

have to be taken into account such as the kinetics of some of the

reaction steps involved. These factors together mean that a higher

potential is required for the reduction and oxidation of water than

predicted, and these are termed overpotentials. Experimentally it is known that overpotentials depend on the design of the cell and the nature of the electrodes.

For the electrolysis of a neutral (pH 7) sodium chloride

solution, the reduction of sodium ion is thermodynamically very

difficult and water is reduced evolving hydrogen leaving hydroxide ions

in solution. At the anode the oxidation of chlorine is observed rather

than the oxidation of water since the overpotential for the oxidation of

chloride to chlorine is lower than the overpotential for the oxidation of water to oxygen. The hydroxide ions and dissolved chlorine gas react further to form hypochlorous acid. The aqueous solutions resulting from this process is called electrolyzed water and is used as a disinfectant and cleaning agent.

Research trends

Electrolysis of carbon dioxide

The electrochemical reduction or electrocatalytic conversion of CO2 can produce value-added chemicals such methane, ethylene, ethane, etc. The electrolysis of carbon dioxide gives formate or carbon monoxide, but sometimes more elaborate organic compounds such as ethylene. This technology is under research as a carbon-neutral route to organic compounds.

Electrolysis of acidified water

Electrolysis of water produces hydrogen.

- 2 H2O(l) → 2 H2(g) + O2(g); E0 = +1.229 V

The energy efficiency

of water electrolysis varies widely. The efficiency of an electrolyser

is a measure of the enthalpy contained in the hydrogen (to undergo

combustion with oxygen, or some other later reaction), compared with the

input electrical energy. Heat/enthalpy values for hydrogen are well

published in science and engineering texts, as 144 MJ/kg. Note that

fuel cells (not electrolysers) cannot use this full amount of

heat/enthalpy, which has led to some confusion when calculating

efficiency values for both types of technology. In the reaction, some

energy is lost as heat. Some reports quote efficiencies between 50% and

70% for alkaline electrolysers; however, much higher practical

efficiencies are available with the use of PEM (Polymer Electrolyte Membrane electrolysis) and catalytic technology, such as 95% efficiency.

NREL

estimated that 1 kg of hydrogen (roughly equivalent to 3 kg, or 4 L, of

petroleum in energy terms) could be produced by wind powered

electrolysis for between $5.55 in the near term and $2.27 in the long

term.

About 4% of hydrogen gas produced worldwide is generated by

electrolysis, and normally used onsite. Hydrogen is used for the

creation of ammonia for fertilizer via the Haber process, and converting heavy petroleum sources to lighter fractions via hydrocracking.

Carbon/hydrocarbon assisted water electrolysis (CAWE)

Recently, to reduce the energy input, the utilization of carbon (coal), alcohols (hydrocarbon solution), and organic solution (glycerol, formic acid, ethylene glycol, etc.) with co-electrolysis of water has been proposed as a viable option.

The carbon/hydrocarbon assisted water electrolysis (so-called CAWE)

process for hydrogen generation would perform this operation in a single

electrochemical

reactor. This system energy balance can be required only around 40%

electric input with 60% coming from the chemical energy of carbon or

hydrocarbon.

This process utilizes solid coal/carbon particles or powder as fuels

dispersed in acid/alkaline electrolyte in the form of slurry and the

carbon contained source co-assist in the electrolysis process as

following theoretical overall reactions:

Carbon/Coal slurry (C + 2H2O) -> CO2 + 2H2 E' = 0.21 V (reversible voltage) / E' = 0.46 V (thermo-neutral voltage)

or

Carbon/Coal slurry (C + H2O) -> CO + H2 E' = 0.52 V reversible voltage) / E' = 0.91 V (thermo-neutral voltage)

Thus, this CAWE approach is that the actual cell overpotential

can be significantly reduced to below 1 V as compared to 1.5 V for

conventional water electrolysis.

Electrocrystallization

A

specialized application of electrolysis involves the growth of

conductive crystals on one of the electrodes from oxidized or reduced

species that are generated in situ. The technique has been used to

obtain single crystals of low-dimensional electrical conductors, such as

charge-transfer salts.

History

Scientific pioneers of electrolysis include:

Pioneers of batteries: