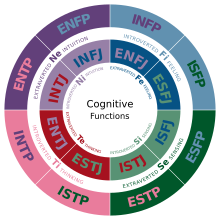

A chart with descriptions of each Myers–Briggs personality type and the four dichotomies central to the theory

The Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is an introspective self-report questionnaire with the purpose of indicating differing psychological preferences in how people perceive the world around them and make decisions.

The MBTI was constructed by Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers. It is based on the conceptual theory proposed by Carl Jung,

who had speculated that humans experience the world using four

principal psychological functions – sensation, intuition, feeling, and

thinking – and that one of these four functions is dominant for a person

most of the time.

The MBTI was constructed for normal populations and emphasizes the value of naturally occurring differences.

"The underlying assumption of the MBTI is that we all have specific

preferences in the way we construe our experiences, and these

preferences underlie our interests, needs, values, and motivation."

Although popular in the business sector, the MBTI exhibits

significant scientific (psychometric) deficiencies, notably including

poor validity

(i.e. not measuring what it purports to measure, not having predictive

power or not having items that can be generalized), poor reliability (giving different results for the same person on different occasions), measuring categories that are not independent (some dichotomous traits have been noted to correlate with each other), and not being comprehensive (due to missing neuroticism). The four scales used in the MBTI have some correlation with four of the Big Five personality traits, which are a more commonly accepted framework.

History

Katharine Cook Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myers extrapolated their MBTI theory from Carl Jung's writings in his book Psychological Types.

Katharine Cook Briggs began her research into personality

in 1917. Upon meeting her future son-in-law, she observed marked

differences between his personality and that of other family members.

Briggs embarked on a project of reading biographies, and subsequently

developed a typology wherein she proposed four temperaments: meditative

(or thoughtful), spontaneous, executive, and social.

After the English translation of Jung's book Psychological Types

was published in 1923 (first published in German in 1921), she

recognized that Jung's theory was similar to, but went far beyond, her

own. Briggs's four types were later identified as corresponding to the IXXXs, EXXPs, EXTJs and EXFJs. Her first publications were two articles describing Jung's theory, in the journal New Republic

in 1926 ("Meet Yourself Using the Personality Paint Box") and 1928 ("Up

From Barbarism"). After extensively studying the work of Jung, Briggs

and her daughter extended their interest in human behavior into efforts

to turn the theory of psychological types to practical use.

Briggs's daughter, Isabel Briggs Myers, joined her mother's

typological research and progressively took it over entirely. Myers

graduated first in her class from Swarthmore College in 1919 and wrote a mystery novel, Murder Yet to Come,

using typological ideas in 1929, which won the National Detective

Murder Mystery Contest that year. However, neither Myers nor Briggs was

formally educated in the discipline of psychology, and both were

self-taught in the field of psychometric testing. Myers therefore apprenticed herself to Edward N. Hay, who was then personnel manager for a large Philadelphia

bank and went on to start one of the first successful personnel

consulting firms in the United States. From Hay, Myers learned

rudimentary test construction, scoring, validation, and statistical

methods.

Briggs and Myers began creating the indicator during World War II

in the belief that a knowledge of personality preferences would help

women entering the industrial workforce for the first time to identify

the sort of war-time jobs that would be the "most comfortable and

effective" for them. The Briggs Myers Type Indicator Handbook was published in 1944. The indicator changed its name to "Myers–Briggs Type Indicator" in 1956. Myers' work attracted the attention of Henry Chauncey, head of the Educational Testing Service. Under these auspices, the first MBTI Manual

was published in 1962. The MBTI received further support from Donald W.

MacKinnon, head of the Institute of Personality and Social Research at

the University of California, Berkeley; W. Harold Grant, a professor at Michigan State University and Auburn University; and Mary H. McCaulley of the University of Florida.

The publication of the MBTI was transferred to Consulting Psychologists

Press in 1975, and the Center for Applications of Psychological Type

was founded as a research laboratory.

After Myers' death in May 1980, Mary McCaulley updated the MBTI Manual and the second edition was published in 1985. The third edition appeared in 1998.

Origins

Jung's theory of psychological types was not based on controlled scientific studies, but instead on clinical observation, introspection, and anecdote—methods regarded as inconclusive in the modern field of scientific psychology.

Jung's typology theories postulated a sequence of four cognitive

functions (thinking, feeling, sensation, and intuition), each having one

of two polar orientations (extraversion or introversion), giving a

total of eight dominant functions. The MBTI is based on these eight

hypothetical functions, although with some differences in expression

from Jung's model. While the Jungian model offers empirical evidence for the first

three dichotomies, whether the Briggs had evidence for the J-P

preference is unclear.

Differences from Jung

Structured vs. projective personality assessment

The

MBTI takes what is called a "structured" approach to personality

assessment. The responses to items are considered "closed" as they are

interpreted according to the theory of the test constructers in scoring.

This is contrary to the "projective" approach

to personality assessment advocated by psychodynamic theorists such as

Carl Jung. Indeed, Jung was a proponent of the "word association" test,

one of the measures with a "projective" approach. This approach uses

"open-ended" responses that need to be interpreted in the context of the

"whole" person, and not according to the preconceived theory and

concept of the test constructers. It reveals how the unconscious

dispositions, such as hidden emotions and internal conflicts, influence

behaviour. Supporters of the "projective" approach to personality

assessment are critical of the "structured" approach because defense

mechanisms may distort responses to the closed items on structured tests

and biases from the constructers may affect result interpretation.

Judging vs. perception

The

most notable addition of Myers and Briggs ideas to Jung's original

thought is their concept that a given type's fourth letter (J or P)

indicates a person's most preferred extraverted function, which is the

dominant function for extraverted types and the auxiliary function for

introverted types.

Orientation of the tertiary function

Jung

theorized that the dominant function acts alone in its preferred world:

exterior for extraverts and interior for introverts. The remaining

three functions, he suggested, operate in the opposite orientation. Some

MBTI practitioners, however, place doubt on this concept as being a

category error with next to no empirical evidence backing it relative to

other findings with correlation evidence, yet as a theory it still

remains part of Myers and Briggs' extrapolation of their original theory

despite being discounted.

Jung's theory goes as such: if the dominant cognitive function is

introverted then the other functions are extraverted and vice versa.

The MBTI Manual summarizes Jung's work of balance in

psychological type as follows: "There are several references in Jung's

writing to the three remaining functions having an opposite attitudinal

character. For example, in writing about introverts with thinking

dominant ... Jung commented that the counterbalancing functions have an

extraverted character." Using the INTP type as an example, the orientation according to Jung would be as follows:

- Dominant introverted thinking

- Auxiliary extraverted intuition

- Tertiary extraverted sensing

- Inferior extraverted feeling

Concepts

The MBTI Manual states that the indicator "is designed to implement a theory; therefore, the theory must be understood to understand the MBTI". Fundamental to the MBTI is the theory of psychological type as originally developed by Carl Jung. Jung proposed the existence of two dichotomous pairs of cognitive functions:

- The "rational" (judging) functions: thinking and feeling

- The "irrational" (perceiving) functions: sensation and intuition

Jung believed that for every person, each of the functions is expressed primarily in either an introverted or extraverted form.

Based on Jung's original concepts, Briggs and Myers developed their own

theory of psychological type, described below, on which the MBTI is

based. However, although psychologist Hans Eysenck called the MBTI a moderately successful quantification of Jung's original principles as outlined in Psychological Types,

he also said, "[The MBTI] creates 16 personality types which are said

to be similar to Jung's theoretical concepts. I have always found

difficulties with this identification, which omits one half of Jung's

theory (he had 32 types, by asserting that for every conscious

combination of traits there was an opposite unconscious one). Obviously,

the latter half of his theory does not admit of questionnaire

measurement, but to leave it out and pretend that the scales measure

Jungian concepts is hardly fair to Jung."

In any event, both models remain hypothetical, with no controlled

scientific studies supporting either Jung's original concept of type or

the Myers–Briggs variation.

Type

Jung's typological model regards psychological type as similar to left or right handedness:

people are either born with, or develop, certain preferred ways of

perceiving and deciding. The MBTI sorts some of these psychological

differences into four opposite pairs, or "dichotomies",

with a resulting 16 possible psychological types. None of these types

is "better" or "worse"; however, Briggs and Myers theorized that people

innately "prefer" one overall combination of type differences.

In the same way that writing with the left hand is difficult for a

right-hander, so people tend to find using their opposite psychological

preferences more difficult, though they can become more proficient (and

therefore behaviorally flexible) with practice and development.

The 16 types are typically referred to by an abbreviation of four

letters—the initial letters of each of their four type preferences

(except in the case of intuition, which uses the abbreviation "N" to

distinguish it from introversion). For instance:

- ESTJ: extraversion (E), sensing (S), thinking (T), judgment (J)

- INFP: introversion (I), intuition (N), feeling (F), perception (P)

These abbreviations are applied to all 16 types.

Four dichotomies

|

|

Subjective | Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Perception | Intuition/Sensing | Introversion/Extraversion 1 |

| Judging | Feeling/Thinking | Introversion/Extraversion 2 |

|

|

Subjective | Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Deductive | Intuition/Sensing | Introversion/Extraversion |

| Inductive | Feeling/Thinking | Perception/Judging |

The terms used for each dichotomy have specific technical

meanings relating to the MBTI, which differ from their everyday usage.

For example, people who prefer judgment over perception are not

necessarily more "judgmental" or less "perceptive", nor does the MBTI

instrument measure aptitude; it simply indicates for one preference over another.

Someone reporting a high score for extraversion over introversion

cannot be correctly described as more extraverted: they simply have a

clear preference.

Point scores on each of the dichotomies can vary considerably

from person to person, even among those with the same type. However,

Isabel Myers considered the direction of the preference (for example, E

vs. I) to be more important than the degree of the preference (for

example, very clear vs. slight).

The expression of a person's psychological type is more than the sum

of the four individual preferences. The preferences interact through type dynamics and type development.

Attitudes: extraversion/introversion

Myers–Briggs

literature uses the terms extraversion and introversion as Jung first

used them. Extraversion means literally outward-turning and

introversion, inward-turning.

These specific definitions differ somewhat from the popular usage of

the words. Extraversion is the spelling used in MBTI publications.

The preferences for extraversion and introversion are often called "attitudes".

Briggs and Myers recognized that each of the cognitive functions can

operate in the external world of behavior, action, people, and things

("extraverted attitude") or the internal world of ideas and reflection

("introverted attitude"). The MBTI assessment sorts for an overall

preference for one or the other.

People who prefer extraversion draw energy from action: they tend

to act, then reflect, then act further. If they are inactive, their

motivation tends to decline. To rebuild their energy, extraverts need

breaks from time spent in reflection. Conversely, those who prefer

introversion "expend" energy through action: they prefer to reflect,

then act, then reflect again. To rebuild their energy, introverts need

quiet time alone, away from activity.

An extravert's flow is directed outward toward people and

objects, whereas the introvert's is directed inward toward concepts and

ideas. Contrasting characteristics between extraverted and introverted

people include:

- Extraverted are action-oriented, while introverted are thought-oriented.

- Extraverted seek breadth of knowledge and influence, while introverted seek depth of knowledge and influence.

- Extraverted often prefer more frequent interaction, while introverted prefer more substantial interaction.

- Extraverted recharge and get their energy from spending time with people, while introverted recharge and get their energy from spending time alone; they consume their energy through the opposite process.

Functions: sensing/intuition and thinking/feeling

Jung identified two pairs of psychological functions:

- Two perceiving functions: sensation (usually called sensing in MBTI writings) and intuition

- Two judging functions: thinking and feeling

According to Jung's typology model, each person uses one of these

four functions more dominantly and proficiently than the other three;

however, all four functions are used at different times depending on the

circumstances.

Sensing and intuition are the information-gathering (perceiving)

functions. They describe how new information is understood and

interpreted. People who prefer sensing are more likely to trust

information that is in the present, tangible, and concrete: that is,

information that can be understood by the five senses. They tend to

distrust hunches, which seem to come "out of nowhere".

They prefer to look for details and facts. For them, the meaning is in

the data. On the other hand, those who prefer intuition tend to trust

information that is less dependent upon the senses, that can be

associated with other information (either remembered or discovered by

seeking a wider context or pattern). They may be more interested in

future possibilities. For them, the meaning is in the underlying theory

and principles which are manifested in the data.

Thinking and feeling are the decision-making

(judging) functions. The thinking and feeling functions are both used

to make rational decisions, based on the data received from their

information-gathering functions (sensing or intuition). Those who prefer

thinking tend to decide things from a more detached standpoint,

measuring the decision by what seems reasonable, logical, causal,

consistent, and matching a given set of rules. Those who prefer feeling

tend to come to decisions by associating or empathizing with the

situation, looking at it 'from the inside' and weighing the situation to

achieve, on balance, the greatest harmony, consensus and fit,

considering the needs of the people involved. Thinkers usually have

trouble interacting with people who are inconsistent or illogical, and

tend to give very direct feedback to others. They are concerned with the

truth and view it as more important.

As noted already, people who prefer thinking do not necessarily,

in the everyday sense, "think better" than their feeling counterparts,

in the common sense; the opposite preference is considered an equally

rational way of coming to decisions (and, in any case, the MBTI

assessment is a measure of preference, not ability). Similarly, those

who prefer feeling do not necessarily have "better" emotional reactions

than their thinking counterparts. In many cases, however, people who use

thinking functions as either dominant or auxiliary tend to have more

underdeveloped feeling functions, and often have more trouble with

regulating and making healthy and productive decisions based on their

feelings.

Dominant function

A

diagram depicting the cognitive functions of each type: A type's

background color represents its dominant function and its text color

represents its auxiliary function.

According to Jung, people use all four cognitive functions. However,

one function is generally used in a more conscious and confident way.

This dominant function is supported by the secondary (auxiliary)

function, and to a lesser degree the tertiary function. The fourth and

least conscious function is always the opposite of the dominant

function. Myers called this inferior function the "shadow".

The four functions operate in conjunction with the attitudes

(extraversion and introversion). Each function is used in either an

extraverted or introverted way. A person whose dominant function is

extraverted intuition, for example, uses intuition very differently from

someone whose dominant function is introverted intuition.

Lifestyle preferences: judging/perception

Myers

and Briggs added another dimension to Jung's typological model by

identifying that people also have a preference for using either the judging function (thinking or feeling) or their perceiving function (sensing or intuition) when relating to the outside world (extraversion).

Myers and Briggs held that types with a preference for judging

show the world their preferred judging function (thinking or feeling).

So, TJ types tend to appear to the world as logical and FJ types as empathetic. According to Myers, judging types like to "have matters settled".

Those types who prefer perception show the world their preferred

perceiving function (sensing or intuition). So, SP types tend to appear

to the world as concrete and NP types as abstract. According to Myers, perceptive types prefer to "keep decisions open".

For extraverts, the J or P indicates their dominant function; for

introverts, the J or P indicates their auxiliary function. Introverts

tend to show their dominant function outwardly only in matters

"important to their inner worlds". For example:

Because the ENTJ type is extraverted, the J indicates that the

dominant function is the preferred judging function (extraverted

thinking). The ENTJ type introverts the auxiliary perceiving function

(introverted intuition). The tertiary function is sensing and the

inferior function is introverted feeling.

Because the INTJ type is introverted, however, the J instead

indicates that the auxiliary function is the preferred judging function

(extraverted thinking). The INTJ type introverts the dominant perceiving

function (introverted intuition). The tertiary function is feeling and

the inferior function is extraverted sensing.

Format and administration

The

current North American English version of the MBTI Step I includes 93

forced-choice questions (88 are in the European English version).

"Forced-choice" means that a person has to choose only one of two

possible answers to each question. The choices are a mixture of word

pairs and short statements. Choices are not literal opposites, but

chosen to reflect opposite preferences on the same dichotomy.

Participants may skip questions if they feel they are unable to choose.

Using psychometric techniques, such as item response theory,

the MBTI will then be scored and will attempt to identify the

preference, and clarity of preference, in each dichotomy. After taking

the MBTI, participants are usually asked to complete a "Best Fit"

exercise (see below) and then given a readout of their Reported Type,

which will usually include a bar graph and number (Preference Clarity

Index) to show how clear they were about each preference when they

completed the questionnaire.

During the early development of the MBTI, thousands of items were

used. Most were eventually discarded because they did not have high

"midpoint discrimination", meaning the results of that one item did not,

on average, move an individual score away from the midpoint. Using only

items with high midpoint discrimination allows the MBTI to have fewer

items on it, but still provide as much statistical information as other

instruments with many more items with lower midpoint discrimination.

Additional formats

Isabel

Myers had noted that people of any given type shared differences, as

well as similarities. At the time of her death, she was developing a

more in-depth method of measuring how people express and experience

their individual type pattern.

In 1987, an advanced scoring system was developed for the MBTI.

From this was developed the Type Differentiation Indicator (Saunders,

1989) which is a scoring system for the longer MBTI, Form J,

which includes the 290 items written by Myers that had survived her

previous item analyses.

It yields 20 subscales (five under each of the four dichotomous

preference scales), plus seven additional subscales for a new

"Comfort-Discomfort" factor (which purportedly corresponds to the

missing factor of neuroticism).

This factor's scales indicate a sense of overall comfort and

confidence versus discomfort and anxiety. They also load onto one of the

four type dimensions:

guarded-optimistic (also T/F),

defiant-compliant (also T/F),

carefree-worried (also T/F),

decisive-ambivalent (also J/P),

intrepid-inhibited (Also E/I),

leader-follower (Also E/I), and

proactive-distractible (also J/P)

Also included is a composite of these called "strain". There are

also scales for type-scale consistency and comfort-scale consistency.

Reliability of 23 of the 27 TDI subscales is greater than 0.50, "an

acceptable result given the brevity of the subscales" (Saunders, 1989).

In 1989, a scoring system was developed for only the 20 subscales

for the original four dichotomies. This was initially known as "Form K"

or the "Expanded Analysis Report". This tool is now called the "MBTI Step II".

Form J or the TDI included the items (derived from Myers' and

McCaulley's earlier work) necessary to score what became known as "Step

III". (The 1998 MBTI Manual reported that the two instruments were one and the same.)

It was developed in a joint project involving the following

organizations: The Myers-Briggs Company, the publisher of the whole

family of MBTI works; CAPT (Center for Applications of Psychological

Type), which holds all of Myers' and McCaulley's original work; and the

MBTI Trust, headed by Katharine and Peter Myers. Step III was advertised

as addressing type development and the use of perception and judgment

by respondents.

Precepts and ethics

These precepts are generally used in the ethical administration of the MBTI:

- Type not trait

- The MBTI sorts for type; it does not indicate the strength of ability. It allows the clarity of a preference to be ascertained (Bill clearly prefers introversion), but not the strength of preference (Jane strongly prefers extraversion) or degree of aptitude (Harry is good at thinking). In this sense, it differs from trait-based tools such as 16PF. Type preferences are polar opposites: a precept of MBTI is that people fundamentally prefer one thing over the other, not a bit of both.

- Own best judge

- People are considered the best judge of their own type. While the MBTI provides a Reported Type, this is considered only an indication of their probable overall Type. A Best Fit Process is usually used to allow respondents to develop their understanding of the four dichotomies, to form their own hypothesis as to their overall Type, and to compare this against the Reported Type. In more than 20% of cases, the hypothesis and the Reported Type differ in one or more dichotomies. Using the clarity of each preference, any potential for bias in the report, and often, a comparison of two or more whole Types may then help respondents determine their own Best Fit.

- No right or wrong

- No preference or total type is considered better or worse than another. They are all 'Gifts Differing', as emphasized by the title of Isabel Briggs Myers' book on this subject.

- Voluntary

- Compelling anyone to take the MBTI is considered unethical. It should always be taken voluntarily.

- Confidentiality

- The result of the MBTI Reported and Best Fit type are confidential between the individual and administrator, and ethically, not for disclosure without permission.

- Not for selection

- The results of the assessment should not be used to "label, evaluate, or limit the respondent in any way" (emphasis original). Since all types are valuable, and the MBTI measures preferences rather than aptitude, the MBTI is not considered a proper instrument for purposes of employment selection. Many professions contain highly competent individuals of different types with complementary preferences.

- Importance of proper feedback

- People should always be given detailed feedback from a trained administrator and an opportunity to undertake a Best Fit exercise to check against their Reported Type. This feedback can be given in person, by telephone or electronically.

This is one of the most important aspects to consider for ensuring

type-match accuracy. Lacking this component, many users end up

mistyping, by at least one character. This is especially true of

assessments offered for free online by third party providers.

Failing to inform users that the MBTI is premised on a best-match

system, based on user input and decision-making, increases the

likelihood that users will obtain an inaccurate type matching. When this

happens, users are more likely to disregard the results or find the

test of little effect or usefulness.

Type dynamics and development

The interaction of two, three, or four preferences is known as "type

dynamics". Although type dynamics has received little or no empirical

support to substantiate its viability as a scientific theory, Myers and Briggs asserted that for each of the 16 four-preference types, one function is the most dominant

and is likely to be evident earliest in life. A secondary or auxiliary

function typically becomes more evident (differentiated) during teenaged

years and provides balance to the dominant. In normal development,

individuals tend to become more fluent with a third, tertiary function

during mid-life, while the fourth, inferior function remains least

consciously developed. The inferior function is often considered to be

more associated with the unconscious, being most evident in situations

such as high stress (sometimes referred to as being "in the grip" of the

inferior function).

However, the use of type dynamics is disputed: in the conclusion

of various studies on the subject of type dynamics, James H. Reynierse

writes, "Type dynamics has persistent logical problems and is

fundamentally based on a series of category mistakes; it provides, at

best, a limited and incomplete account of type related phenomena"; and

"type dynamics relies on anecdotal evidence, fails most efficacy tests,

and does not fit the empirical facts". His studies gave the clear result

that the descriptions and workings of type dynamics do not fit the real

behavior of people. He suggests getting completely rid of type

dynamics, because it does not help, but hinders understanding of

personality. The presumed order of functions 1 to 4 did only occur in

one out of 540 test results.

The sequence of differentiation of dominant, auxiliary, and tertiary functions through life is termed type development. This is an idealized sequence that may be disrupted by major life events.

The dynamic sequence of functions and their attitudes can be determined in the following way:

- The overall lifestyle preference (J-P) determines whether the judging (T-F) or perceiving (S-N) preference is most evident in the outside world; i.e., which function has an extraverted attitude

- The attitude preference (E-I) determines whether the extraverted function is dominant or auxiliary

- For those with an overall preference for extraversion, the function with the extraverted attitude will be the dominant function. For example, for an ESTJ type the dominant function is the judging function, thinking, and this is experienced with an extraverted attitude. This is notated as a dominant Te. For an ESTP, the dominant function is the perceiving function, sensing, notated as a dominant Se.

- The auxiliary function for extraverts is the secondary preference of the judging or perceiving functions, and it is experienced with an introverted attitude: for example, the auxiliary function for ESTJ is introverted sensing (Si) and the auxiliary for ESTP is introverted thinking (Ti).

- For those with an overall preference for introversion, the function with the extraverted attitude is the auxiliary; the dominant is the other function in the main four letter preference. So the dominant function for ISTJ is introverted sensing (Si) with the auxiliary (supporting) function being extraverted thinking (Te).

- The tertiary function is the opposite preference from the auxiliary. For example, if the Auxiliary is thinking then the Tertiary would be feeling. The attitude of the tertiary is the subject of some debate and therefore is not normally indicated; i.e. if the auxiliary was Te then the tertiary would be F (not Fe or Fi)

- The inferior function is the opposite preference and attitude from the Dominant, so for an ESTJ with dominant Te the inferior would be Fi.

Note that for extraverts, the dominant function is the one most

evident in the external world. For introverts, however, it is the

auxiliary function that is most evident externally, as their dominant

function relates to the interior world.

Some examples of whole types may clarify this further. Taking the ESTJ example above:

- Extraverted function is a judging function (T-F) because of the overall J preference

- Extraverted function is dominant because of overall E preference

- Dominant function is therefore extraverted thinking (Te)

- Auxiliary function is the preferred perceiving function: introverted sensing (Si)

- Tertiary function is the opposite of the Auxiliary: intuition (N)

- Inferior function is the opposite of the Dominant: introverted feeling (Fi)

The dynamics of the ESTJ are found in the primary combination of

extraverted thinking as their dominant function and introverted sensing

as their auxiliary function: the dominant tendency of ESTJs to order

their environment, to set clear boundaries, to clarify roles and

timetables, and to direct the activities around them is supported by

their facility for using past experience in an ordered and systematic

way to help organize themselves and others. For instance, ESTJs may

enjoy planning trips for groups of people to achieve some goal or to

perform some culturally uplifting function. Because of their ease in

directing others and their facility in managing their own time, they

engage all the resources at their disposal to achieve their goals.

However, under prolonged stress or sudden trauma, ESTJs may overuse

their extraverted thinking function and fall into the grip of their

inferior function, introverted feeling. Although the ESTJ can seem

insensitive to the feelings of others in their normal activities, under

tremendous stress, they can suddenly express feelings of being

unappreciated or wounded by insensitivity.

Looking at the diametrically opposite four-letter type, INFP:

- Extraverted function is a perceiving function (S-N) because of the P preference

- Introverted function is dominant because of the I preference

- Dominant function is therefore introverted feeling (Fi)

- Auxiliary function is extraverted intuition (Ne)

- Tertiary function is the opposite of the Auxiliary: sensing (S)

- Inferior function is the opposite of the Dominant: extraverted thinking (Te)

The dynamics of the INFP rest on the fundamental correspondence of

introverted feeling and extraverted intuition. The dominant tendency of

the INFP is toward building a rich internal framework of values and

toward championing human rights. They often devote themselves behind the

scenes to causes such as civil rights or saving the environment. Since

they tend to avoid the limelight, postpone decisions, and maintain a

reserved posture, they are rarely found in executive-director-type

positions of the organizations that serve those causes. Normally, the

INFP dislikes being "in charge" of things. When not under stress, the

INFP radiates a pleasant and sympathetic demeanor, but under extreme

stress, they can suddenly become rigid and directive, exerting their

extraverted thinking erratically.

Every type, and its opposite, is the expression of these interactions, which give each type its unique, recognizable signature.

Cognitive learning styles

The

test is scored by evaluating each answer in terms of what it reveals

about the taker. Each question is relevant to one of the following

cognitive learning styles. Each is not a polar opposite, but a gradual

continuum.

Extraversion/Introversion

The

extraverted types learn best by talking and interacting with others. By

interacting with the physical world, extraverts can process and make

sense of new information. The introverted types prefer quiet reflection

and privacy. Information processing occurs for introverts as they

explore ideas and concepts internally.

Sensing/Intuition

The

second continuum reflects what people focus their attentions on.

Sensing types are good at concrete and tangible things. Intuitive types

are good at abstract things and ideas. Sensing types might enjoy a

learning environment in which the material is presented in a detailed

and sequential manner. Sensing types often attend to what is occurring

in the present, and can move to the abstract after they have established

a concrete experience. Intuitive types might prefer a learning

atmosphere in which an emphasis is placed on meaning and associations.

Insight is valued higher than careful observation, and pattern

recognition occurs naturally for intuitive types.

Thinking/Feeling

The

third continuum reflects a person's decision preferences. Thinking

types desire objective truth and logical principles and are natural at

deductive reasoning. Feeling types place an emphasis on issues and

causes that can be personalized while they consider other people's

motives.

Judging/Perceiving

The

fourth continuum reflects how a person regards complexity. Judging

types tend to have a structured way or theory to approach the world.

Perceiving types tend to be unstructured and keep options open. Judging

types will always try to make accommodation between new information and

their structured world, which might only be changed with discretion.

Perceiving types will be more willing to change without having a prior

structured world.

MBTI Step II

MBTI Step II is an extended version of the Myers–Briggs Type

Indicator. Step II provides additional depth and clarification within

each of the four original MBTI preference pairs or "dichotomies".

Isabel Briggs Myers had noted that people with any given type

shared differences as well as similarities. At the time of her death she

was developing a more in-depth method to offer clues about how each

person expresses and experiences their type pattern, which is called

MBTI Step II. In the 1980s, Kathy Myers and Peter Myers developed a team of type experts, and a factor analysis was conducted.

This resulted in the identification of five subscales (with

corresponding pairs of facets each) for each of the four MBTI scales. These subscales break down the uniqueness of individuals into greater detail,

by bringing to light the subtle nuances of personality type; thus

avoiding the reduction of all of personality to just the 16 types.

Concepts

There are a number of new concepts introduced in Step II that are not part of MBTI Step I, including:-

- Each of the original four preference pairs (dichotomies) is broken down into five "facets". Whilst the facets reflect different aspects of the main dichotomy, they do not combine to the whole of the original preference. In other words, you can not say that, for example, a preference for Thinking over Feeling is simply a combination of the five Thinking facets (logical, reasonable, questioning, critical and tough).

- Whilst in MBTI Step I, each of the preference pairs is considered to be a polar opposite, some of the Step II facets are more "trait- like" - i.e. there may be degrees of strength or aptitude.

- Any individual taking Step II is likely to find some of the facets to be aligned to the overall preference (in preference, e.g. preference for the Logical facet and an overall Thinking preference); others may be more flexible or variable (mid zone, e.g. no clear preference for either the Concrete or Abstract facet despite an overall Intuition preference); and there may be some facets that are opposite to the overall preference (out of preference, also called "OOPS", e.g. a preference for the Intimate over the Gregarious facet despite an overall Extraversion preference)

Applications

MBTI

Step II can be used in the same applications areas as MBTI Step I, for

example, coaching, team dynamics and relationship counselling.

It is particularly used in one-to-one executive coaching and in

working with teams who have already had some exposure to MBTI Step I. It

is also useful in helping individuals to clarify their MBTI Step I

"best fit type".

Correlations with other instruments

Keirsey temperaments

David Keirsey

mapped four "temperaments" to the existing Myers–Briggs system

groupings: SP, SJ, NF and NT; this often results in confusion of the two

theories. However, the Keirsey Temperament Sorter is not directly associated with the official Myers–Briggs Type Indicator.

|

ISITEJ

Inspector

|

ISIFEJ

Protector

|

INIFEJ

Counselor

|

INITEJ

Mastermind

|

|

ISETIP

Crafter

|

ISEFIP

Composer

|

INEFIP

Healer

|

INETIP

Architect

|

|

ESETIP

Promoter

|

ESEFIP

Performer

|

ENEFIP

Champion

|

ENETIP

Inventor

|

|

ESITEJ

Supervisor

|

ESIFEJ

Provider

|

ENIFEJ

Teacher

|

ENITEJ

Fieldmarshal

|

Big Five

McCrae and Costa based their Five Factor Model (FFM) on Goldberg's Big Five theory. McCrae and Costa present correlations between the MBTI scales and the currently popular Big Five personality constructs measured, for example, by the NEO-PI-R.

The five purported personality constructs have been labeled:

extraversion, openness, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and

neuroticism (emotional instability), although there is not universal

agreement on the Big Five theory and the related Five-Factor Model

(FFM).

These findings led McCrae and Costa to conclude that,

"correlational analyses showed that the four MBTI indices did measure

aspects of four of the five major dimensions of normal personality. The

five-factor model provides an alternative basis for interpreting MBTI

findings within a broader, more commonly shared conceptual framework."

However, "there was no support for the view that the MBTI measures truly

dichotomous preferences or qualitatively distinct types, instead, the

instrument measures four relatively independent dimensions."

Personality disorders

One study found personality disorders as described by the DSM

overall to correlate modestly with I, N, T, and P, although the

associations varied significantly by disorder. The only two disorders

with significant correlations of all four MBTI dimensions were schizotypal (INTP) and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (ISTJ).

Criticism

The validity (statistical validity and test validity) of the MBTI as a psychometric instrument has been the subject of much criticism.

It has been estimated that between a third and a half of the

published material on the MBTI has been produced for the special

conferences of the Center for the Application of Psychological Type

(which provide the training in the MBTI, and are funded by sales of the

MBTI) or as papers in the Journal of Psychological Type (which is edited and supported by Myers–Briggs advocates and by sales of the indicator). It has been argued that this reflects a lack of critical scrutiny. Many of the studies that endorse MBTI are methodologically weak or unscientific.

A 1996 review by Gardner and Martinko concluded: "It is clear that

efforts to detect simplistic linkages between type preferences and

managerial effectiveness have been disappointing. Indeed, given the

mixed quality of research and the inconsistent findings, no definitive

conclusion regarding these relationships can be drawn."

Psychometric specialist Robert Hogan wrote: "Most personality psychologists regard the MBTI as little more than an elaborate Chinese fortune cookie ..."

No evidence for dichotomies

As described in the § Four dichotomies

section, Isabel Myers considered the direction of the preference (for

example, E vs. I) to be more important than the degree of the

preference. Statistically, this would mean that scores on each MBTI

scale would show a bimodal distribution

with most people scoring near the ends of the scales, thus dividing

people into either, e.g., an extroverted or an introverted psychological

type. However, most studies have found that scores on the individual

scales were actually distributed in a centrally peaked manner, similar

to a normal distribution,

indicating that the majority of people were actually in the middle of

the scale and were thus neither clearly introverted nor extroverted.

Most personality traits do show a normal distribution of scores from low

to high, with about 15% of people at the low end, about 15% at the high

end and the majority of people in the middle ranges. But in order for

the MBTI to be scored, a cut-off line is used at the middle of each

scale and all those scoring below the line are classified as a low type

and those scoring above the line are given the opposite type. Thus,

psychometric assessment research fails to support the concept of type, but rather shows that most people lie near the middle of a continuous curve.

"Although we do not conclude that the absence of bimodality necessarily

proves that the MBTI developers' theory-based assumption of categorical

"types" of personality is invalid, the absence of empirical bimodality

in IRT-based

research of MBTI scores does indeed remove a potentially powerful line

of evidence that was previously available to "type" advocates to cite in

defense of their position."

No evidence for "dynamic" type stack

Some

MBTI supporters argue that the application of type dynamics to MBTI

(e.g. where inferred "dominant" or "auxiliary" functions like Se /

"Extraverted Sensing" or Ni / "Introverted Intuition" are presumed to

exist) is a logical category error that has little empirical evidence

backing it.

Instead, they argue that Myers Briggs validity as a psychometric tool

is highest when each type category is viewed independently as a

dichotomy.

Validity and utility

The content of the MBTI scales is problematic. In 1991, a National Academy of Sciences

committee reviewed data from MBTI research studies and concluded that

only the I-E scale has high correlations with comparable scales of other

instruments and low correlations with instruments designed to assess

different concepts, showing strong validity. In contrast, the S-N and

T-F scales show relatively weak validity. The 1991 review committee

concluded at the time there was "not sufficient, well-designed research

to justify the use of the MBTI in career counseling programs". This study based its measurement of validity

on "criterion-related validity (i.e., does the MBTI predict specific

outcomes related to interpersonal relations or career success/job

performance?)."

The committee stressed the discrepancy between popularity of the MBTI

and research results stating, "the popularity of this instrument in the

absence of proven scientific worth is troublesome."

There is insufficient evidence to make claims about utility,

particularly of the four letter type derived from a person's responses

to the MBTI items.

Lack of objectivity

The accuracy of the MBTI depends on honest self-reporting. Unlike some personality questionnaires, such as the 16PF Questionnaire, the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, or the Personality Assessment Inventory, the MBTI does not use validity scales to assess exaggerated or socially desirable responses. As a result, individuals motivated to do so can fake their responses, and one study found that the MBTI judgment/perception dimension correlates weakly with the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire lie scale. If respondents "fear they have something to lose, they may answer as they assume they should."

However, the MBTI ethical guidelines state, "It is unethical and in

many cases illegal to require job applicants to take the Indicator if

the results will be used to screen out applicants."

The intent of the MBTI is to provide "a framework for understanding

individual differences, and ... a dynamic model of individual

development".

Terminology

The terminology of the MBTI has been criticized as being very "vague and general", so as to allow any kind of behavior to fit any personality type, which may result in the Forer effect, where people give a high rating to a positive description that supposedly applies specifically to them. Others argue that while the MBTI type descriptions are brief, they are also distinctive and precise.

Some theorists, such as David Keirsey, have expanded on the MBTI

descriptions, providing even greater detail. For instance, Keirsey's

descriptions of his four temperaments,

which he correlated with the sixteen MBTI personality types, show how

the temperaments differ in terms of language use, intellectual

orientation, educational and vocational interests, social orientation,

self-image, personal values, social roles, and characteristic hand

gestures.

Factor analysis

Researchers have reported that the JP and the SN scales correlate with one another.

One factor-analytic study based on (N=1291) college-aged students found

six different factors instead of the four purported dimensions, thereby

raising doubts as to the construct validity of the MBTI.

Correlates

According

to Hans Eysenck: "The main dimension in the MBTI is called E-I, or

extraversion-introversion; this is mostly a sociability scale,

correlating quite well with the MMPI social introversion scale

(negatively) and the Eysenck Extraversion scale (positively).

Unfortunately, the scale also has a loading on neuroticism, which

correlates with the introverted end. Thus introversion correlates

roughly (i.e. averaging values for males and females) -.44 with

dominance, -.24 with aggression, +.37 with abasement, +.46 with

counselling readiness, -.52 with self-confidence, -.36 with personal

adjustment, and -.45 with empathy. The failure of the scale to

disentangle Introversion and Neuroticism (there is no scale for neurotic

and other psychopathological attributes in the MBTI) is its worst

feature, only equalled by the failure to use factor analysis in order to

test the arrangement of items in the scale."

Reliability

The test-retest reliability

of the MBTI tends to be low. Large numbers of people (between 39% and

76% of respondents) obtain different type classifications when retaking

the indicator after only five weeks. In Fortune Magazine (May 15, 2013), an article titled "Have we all been duped by the Myers-Briggs Test" stated:

| “ | The

interesting – and somewhat alarming – fact about the MBTI is that,

despite its popularity, it has been subject to sustained criticism by

professional psychologists for over three decades. One problem is that

it displays what statisticians call low "test-retest reliability." So if

you retake the test after only a five-week gap, there's around a 50%

chance that you will fall into a different personality category compared

to the first time you took the test.

A second criticism is that the MBTI mistakenly assumes that

personality falls into mutually exclusive categories. ... The

consequence is that the scores of two people labelled "introverted" and

"extroverted" may be almost exactly the same, but they could be placed

into different categories since they fall on either side of an imaginary

dividing line.

|

” |

Within each dichotomy scale, as measured on Form G, about 83%

of categorizations remain the same when people are retested within nine

months and around 75% when retested after nine months. About 50% of

people re-administered the MBTI within nine months remain the same

overall type and 36% the same type after more than nine months. For Form M (the most current form of the MBTI instrument), the MBTI Manual reports that these scores are higher (p. 163, Table 8.6).

In one study, when people were asked to compare their preferred

type to that assigned by the MBTI assessment, only half of people chose

the same profile.

It has been argued that criticisms regarding the MBTI mostly come

down to questions regarding the validity of its origins, not questions

regarding the validity of the MBTI's usefulness.

Others argue that the MBTI can be a reliable measurement of

personality; it just so happens that "like all measures, the MBTI yields

scores that are dependent on sample characteristics and testing

conditions".

Utility

Isabel Myers claimed that the proportion of different personality types varied by choice of career or course of study.

However, researchers examining the proportions of each type within

varying professions report that the proportion of MBTI types within each

occupation is close to that within a random sample of the population.

Some researchers have expressed reservations about the relevance of

type to job satisfaction, as well as concerns about the potential misuse

of the instrument in labeling people.

CPP-The Myers-Briggs Company became the exclusive publisher of

the MBTI in 1975. They call it "the world's most widely used personality

assessment", with as many as two million assessments administered

annually.

The Myers-Briggs Company and other proponents state that the indicator

meets or exceeds the reliability of other psychological instruments and

cite reports of individual behavior.

Although meta-analysis claim support for validity and reliability, studies suggest that the MBTI "lacks convincing validity data" and that it is pseudoscience.

The MBTI has poor predictive validity of employees' job performance ratings.

As noted above under Precepts and ethics, the MBTI measures

preferences, not ability. The use of the MBTI as a predictor of job

success is expressly discouraged in the Manual.

It is argued that the MBTI continues to be popular because many people

lack psychometric sophistication, it is not difficult to understand,

and there are many supporting books, websites and other sources which

are readily available to the general public.