how pesticides are used

The impact of pesticides consists of the effects of pesticides on non-target species. Pesticides are chemical preparations used to kill fungal or animal pests. Over 98% of sprayed insecticides and 95% of herbicides reach a destination other than their target species, because they are sprayed or spread across entire agricultural fields. Runoff

can carry pesticides into aquatic environments while wind can carry

them to other fields, grazing areas, human settlements and undeveloped

areas, potentially affecting other species. Other problems emerge from

poor production, transport and storage practices.

Over time, repeated application increases pest resistance, while its

effects on other species can facilitate the pest's resurgence.

Each pesticide or pesticide class comes with a specific set of

environmental concerns. Such undesirable effects have led many

pesticides to be banned, while regulations have limited and/or reduced

the use of others. Over time, pesticides have generally become less

persistent and more species-specific, reducing their environmental

footprint. In addition the amounts of pesticides applied per hectare

have declined, in some cases by 99%. The global spread of pesticide use,

including the use of older/obsolete pesticides that have been banned in

some jurisdictions, has increased overall.

Agriculture and the environment

The

arrival of humans in an area, to live or to conduct agriculture,

necessarily has environmental impacts. These range from simple crowding

out of wild plants in favor of more desirable cultivars to larger scale

impacts such as reducing biodiversity by reducing food availability of native species, which can propagate across food chains. The use of agricultural chemicals such as fertilizer and des magnify those impacts. While advances in agrochemistry

have reduced those impacts, for example by the replacement of

long-lived chemicals with those that reliably degrade, even in the best

case they remain substantial. These effects are magnified by the use of

older chemistries and poor management practices.

History

While concern for ecotoxicology

began with acute poisoning events in the late 19th century; public

concern over the undesirable environmental effects of chemicals arose in

the early 1960s with the publication of Rachel Carson′s book, Silent Spring. Shortly thereafter, DDT, originally used to combat malaria,

and its metabolites were shown to cause population-level effects in

raptorial birds. Initial studies in industrialized countries focused on

acute mortality effects mostly involving birds or fish.

Data on pesticide usage remain scattered and/or not publicly

available (3). The common practice of incident registration is

inadequate for understanding the entirety of effects.

Since 1990, research interest has shifted from documenting

incidents and quantifying chemical exposure to studies aimed at linking

laboratory, mesocosm

and field experiments. The proportion of effect-related publications

has increased. Animal studies mostly focus on fish, insects, birds,

amphibians and arachnids.

Since 1993, the United States and the European Union have updated pesticide risk assessments, ending the use of acutely toxic organophosphate and carbamate

insecticides. Newer pesticides aim at efficiency in target and minimum

side effects in nontarget organisms. The phylogenetic proximity of

beneficial and pest species complicates the project.

One of the major challenges is to link the results from cellular

studies through many levels of increasing complexity to ecosystems.

The concept (borrowed from nuclear physics) of a half-life has been utilized for pesticides in plants,

and certain authors maintain that pesticide risk and impact assessment

models rely on and are sensitive to information describing dissipation

from plants. Half-life for pesticides is explained in two NPIC fact sheets. Known degradation pathways are through: photolysis, chemical dissociation, sorption, bioaccumulation and plant or animal metabolism. A USDA fact sheet published in 1994 lists the soil adsorption coefficient and soil half-life for then-commonly used pesticides.

Specific pesticide effects

| Pesticide/class | Effect(s) |

|---|---|

| Organochlorine DDT/DDE | Egg shell thinning in raptorial birds |

| Endocrine disruptor | |

| Thyroid disruption properties in rodents, birds, amphibians and fish | |

| Acute mortality attributed to inhibition of acetylcholine esterase activity | |

| DDT | Carcinogen |

| Endocrine disruptor | |

| DDT/Diclofol, Dieldrin and Toxaphene | Juvenile population decline and adult mortality in wildlife reptiles |

| DDT/Toxaphene/Parathion | Susceptibility to fungal infection |

| Triazine | Earthworms became infected with monocystid gregarines |

| Chlordane | Interact with vertebrate immune systems |

| Carbamates, the phenoxy herbicide 2,4-D, and atrazine | Interact with vertebrate immune systems |

| Anticholinesterase | Bird poisoning |

| Animal infections, disease outbreaks and higher mortality. | |

| Organophosphate | Thyroid disruption properties in rodents, birds, amphibians and fish |

| Acute mortality attributed to inhibition of acetylcholine esterase activity | |

| Immunotoxicity, primarily caused by the inhibition of serine hydrolases or esterases | |

| Oxidative damage | |

| Modulation of signal transduction pathways | |

| Impaired metabolic functions such as thermoregulation, water and/or food intake and behavior, impaired development, reduced reproduction and hatching success in vertebrates. | |

| Carbamate | Thyroid disruption properties in rodents, birds, amphibians and fish |

| Impaired metabolic functions such as thermoregulation, water and/or food intake and behavior, impaired development, reduced reproduction and hatching success in vertebrates. | |

| Interact with vertebrate immune systems | |

| Acute mortality attributed to inhibition of acetylcholine esterase activity | |

| Phenoxy herbicide 2,4-D | Interact with vertebrate immune systems |

| Atrazine | Interact with vertebrate immune systems |

| Reduced northern leopard frog (Rana pipiens) populations because atrazine killed phytoplankton, thus allowing light to penetrate the water column and periphyton to assimilate nutrients released from the plankton. Periphyton growth provided more food to grazers, increasing snail populations, which provide intermediate hosts for trematode. | |

| Pyrethroid | Thyroid disruption properties in rodents, birds, amphibians and fish |

| Thiocarbamate | Thyroid disruption properties in rodents, birds, amphibians and fish |

| Triazine | Thyroid disruption properties in rodents, birds, amphibians and fish |

| Triazole | Thyroid disruption properties in rodents, birds, amphibians and fish |

| Impaired metabolic functions such as thermoregulation, water and/or food intake and behavior, impaired development, reduced reproduction and hatching success in vertebrates. | |

| Neonicotinoic/Nicotinoid | respiratory, cardiovascular, neurological, and immunological toxicity in rats and humans |

| Disrupt biogenic amine signaling and cause subsequent olfactory dysfunction, as well as affecting foraging behavior, learning and memory. | |

| Imidacloprid, Imidacloprid/pyrethroid λ-cyhalothrin | Impaired foraging, brood development, and colony success in terms of growth rate and new queen production. |

| Thiamethoxam | High honey bee worker mortality due to homing failure (risks for colony collapse remain controversial) |

| Spinosyns | Affect various physiological and behavioral traits of beneficial arthropods, particularly hymenopterans |

| Bt corn/Cry | Reduced abundance of some insect taxa, predominantly susceptible Lepidopteran herbivores as well as their predators and parasitoids. |

| Herbicide | Reduced food availability and adverse secondary effects on soil invertebrates and butterflies |

| Decreased species abundance and diversity in small mammals. | |

| Benomyl | Altered the patch-level floral display and later a two-thirds reduction of the total number of bee visits and in a shift in the visitors from large-bodied bees to small-bodied bees and flies |

| Herbicide and planting cycles | Reduced survival and reproductive rates in seed-eating or carnivorous birds |

Air

Spraying a mosquito pesticide over a city

Pesticides can contribute to air pollution. Pesticide drift occurs when pesticides suspended in the air as particles are carried by wind to other areas, potentially contaminating them. Pesticides that are applied to crops can volatilize and may be blown by winds into nearby areas, potentially posing a threat to wildlife.

Weather conditions at the time of application as well as temperature

and relative humidity change the spread of the pesticide in the air. As

wind velocity increases so does the spray drift and exposure. Low

relative humidity and high temperature result in more spray evaporating.

The amount of inhalable pesticides in the outdoor environment is

therefore often dependent on the season. Also, droplets of sprayed pesticides or particles from pesticides applied as dusts may travel on the wind to other areas, or pesticides may adhere to particles that blow in the wind, such as dust particles. Ground spraying produces less pesticide drift than aerial spraying does. Farmers can employ a buffer zone around their crop, consisting of empty land or non-crop plants such as evergreen trees to serve as windbreaks and absorb the pesticides, preventing drift into other areas. Such windbreaks are legally required in the Netherlands.

Pesticides that are sprayed on to fields and used to fumigate soil can give off chemicals called volatile organic compounds, which can react with other chemicals and form a pollutant called tropospheric ozone. Pesticide use accounts for about 6 percent of total tropospheric ozone levels.

Water

Pesticide pathways

In the United States, pesticides were found to pollute every stream and over 90% of wells sampled in a study by the US Geological Survey. Pesticide residues have also been found in rain and groundwater.

Studies by the UK government showed that pesticide concentrations

exceeded those allowable for drinking water in some samples of river

water and groundwater.

Pesticide impacts on aquatic systems are often studied using a hydrology transport model to study movement and fate of chemicals in rivers and streams. As early as the 1970s

quantitative analysis of pesticide runoff was conducted in order to

predict amounts of pesticide that would reach surface waters.

There are four major routes through which pesticides reach the

water: it may drift outside of the intended area when it is sprayed, it

may percolate, or leach, through the soil, it may be carried to the water as runoff, or it may be spilled, for example accidentally or through neglect. They may also be carried to water by eroding soil. Factors that affect a pesticide's ability to contaminate water include its water solubility,

the distance from an application site to a body of water, weather, soil

type, presence of a growing crop, and the method used to apply the

chemical.

United States regulations

In the US, maximum limits of allowable concentrations for individual pesticides in drinking water are set by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for public water systems. (There are no federal standards for private wells.) Ambient water quality standards

for pesticide concentrations in water bodies are principally developed

by state environmental agencies, with EPA oversight. These standards may

be issued for individual water bodies, or may apply statewide.

United Kingdom regulations

The

United Kingdom sets Environmental Quality Standards (EQS), or maximum

allowable concentrations of some pesticides in bodies of water above

which toxicity may occur.

European Union regulations

The European Union also regulates maximum concentrations of pesticides in water.

Soil

The extensive

use of pesticides in agricultural production can degrade and damage the

community of microorganisms living in the soil, particularly when these

chemicals are overused or misused. The full impact of pesticides on

soil microorganisms is still not entirely understood; many studies have

found deleterious effects of pesticides on soil microorganisms and

biochemical processes, while others have found that the residue of some

pesticides can be degraded and assimilated by microorganisms.

The effect of pesticides on soil microorganisms is impacted by the

persistence, concentration, and toxicity of the applied pesticide, in

addition to various environmental factors.

This complex interaction of factors makes it difficult to draw

definitive conclusions about the interaction of pesticides with the soil

ecosystem. In general, long-term pesticide application can disturb the

biochemical processes of nutrient cycling.

Many of the chemicals used in pesticides are persistent soil contaminants, whose impact may endure for decades and adversely affect soil conservation.

The use of pesticides decreases the general biodiversity in the soil. Not using the chemicals results in higher soil quality, with the additional effect that more organic matter in the soil allows for higher water retention. This helps increase yields for farms in drought years, when organic farms have had yields 20-40% higher than their conventional counterparts.

A smaller content of organic matter in the soil increases the amount

of pesticide that will leave the area of application, because organic

matter binds to and helps break down pesticides.

Degradation and sorption are both factors which influence the

persistence of pesticides in soil. Depending on the chemical nature of

the pesticide, such processes control directly the transportation from

soil to water, and in turn to air and our food. Breaking down organic

substances, degradation, involves interactions among microorganisms in

the soil. Sorption affects bioaccumulation of pesticides which are

dependent on organic matter in the soil. Weak organic acids have been

shown to be weakly sorbed by soil, because of pH and mostly acidic

structure. Sorbed chemicals have been shown to be less accessible to

microorganisms. Aging mechanisms are poorly understood but as residence

times in soil increase, pesticide residues become more resistant to

degradation and extraction as they lose biological activity.

Effect on plants

Crop spraying

Nitrogen fixation, which is required for the growth of higher plants, is hindered by pesticides in soil. The insecticides DDT, methyl parathion, and especially pentachlorophenol have been shown to interfere with legume-rhizobium chemical signaling. Reduction of this symbiotic chemical signaling results in reduced nitrogen fixation and thus reduced crop yields. Root nodule formation in these plants saves the world economy $10 billion in synthetic nitrogen fertilizer every year.

Pesticides can kill bees and are strongly implicated in pollinator decline, the loss of species that pollinate plants, including through the mechanism of Colony Collapse Disorder, in which worker bees from a beehive or western honey bee colony abruptly disappear. Application of pesticides to crops that are in bloom can kill honeybees, which act as pollinators. The USDA and USFWS

estimate that US farmers lose at least $200 million a year from reduced

crop pollination because pesticides applied to fields eliminate about a

fifth of honeybee colonies in the US and harm an additional 15%.

On the other side, pesticides have some direct harmful effect on

plant including poor root hair development, shoot yellowing and reduced

plant growth.

Effect on animals

In England, the use of pesticides in gardens and farmland has seen a reduction in the number of common chaffinches

Many kinds of animals are harmed by pesticides, leading many countries to regulate pesticide usage through Biodiversity Action Plans.

Animals including humans may be poisoned by pesticide residues

that remain on food, for example when wild animals enter sprayed fields

or nearby areas shortly after spraying.

Pesticides can eliminate some animals' essential food sources,

causing the animals to relocate, change their diet or starve. Residues

can travel up the food chain; for example, birds can be harmed when they eat insects and worms that have consumed pesticides.

Earthworms digest organic matter and increase nutrient content in the

top layer of soil. They protect human health by ingesting decomposing

litter and serving as bioindicators of soil activity. Pesticides have

had harmful effects on growth and reproduction on earthworms. Some pesticides can bioaccumulate,

or build up to toxic levels in the bodies of organisms that consume

them over time, a phenomenon that impacts species high on the food chain

especially hard.

Birds

Index of number of common farmland birds in the European Union and selected European countries, base equal to 100 in 1990

Sweden

Netherlands

France

United Kingdom

European Union

Germany

Switzerland

The US Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that 72 million birds are killed by pesticides in the United States each year. Bald eagles are common examples of nontarget organisms that are impacted by pesticide use. Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring dealt with damage to bird species due to pesticide bioaccumulation. There is evidence that birds are continuing to be harmed by pesticide use. In the farmland of the United Kingdom,

populations of ten different bird species declined by 10 million

breeding individuals between 1979 and 1999, allegedly from loss of plant

and invertebrate species on which the birds feed. Throughout Europe,

116 species of birds were threatened as of 1999. Reductions in bird

populations have been found to be associated with times and areas in

which pesticides are used. DDE-induced egg shell thinning has especially affected European and North American bird populations. From 1990 to 2014 the number of common farmland birds has declined in the European Union as a whole and in France, Belgium and Sweden; in Germany, which relies more on organic farming and less on pesticides the decline has been slower; in Switzerland, which does not rely much on intensive agriculture, after a decline in the early 2000s the level has returned to the one of 1990. In another example, some types of fungicides used in peanut

farming are only slightly toxic to birds and mammals, but may kill

earthworms, which can in turn reduce populations of the birds and

mammals that feed on them.

Some pesticides come in granular form. Wildlife may eat the

granules, mistaking them for grains of food. A few granules of a

pesticide may be enough to kill a small bird.

The herbicide paraquat, when sprayed onto bird eggs, causes growth abnormalities in embryos

and reduces the number of chicks that hatch successfully, but most

herbicides do not directly cause much harm to birds. Herbicides may

endanger bird populations by reducing their habitat.

Aquatic life

Using an aquatic herbicide

Wide field margins can reduce fertilizer and pesticide pollution in streams and rivers

Fish and other aquatic biota may be harmed by pesticide-contaminated water. Pesticide surface runoff into rivers and streams can be highly lethal to aquatic life, sometimes killing all the fish in a particular stream.

Application of herbicides to bodies of water can cause fish kills when the dead plants decay and consume the water's oxygen, suffocating the fish. Herbicides such as copper sulfite that are applied to water to kill plants are toxic to fish and other water animals at concentrations

similar to those used to kill the plants. Repeated exposure to

sublethal doses of some pesticides can cause physiological and

behavioral changes that reduce fish populations, such as abandonment of

nests and broods, decreased immunity to disease and decreased predator

avoidance.

Application of herbicides to bodies of water can kill plants on which fish depend for their habitat.

Pesticides can accumulate in bodies of water to levels that kill off zooplankton, the main source of food for young fish.

Pesticides can also kill off insects on which some fish feed, causing

the fish to travel farther in search of food and exposing them to

greater risk from predators.

The faster a given pesticide breaks down in the environment, the

less threat it poses to aquatic life. Insecticides are typically more

toxic to aquatic life than herbicides and fungicides.

Amphibians

In the past several decades, amphibian populations have declined across the world, for unexplained reasons which are thought to be varied but of which pesticides may be a part.

Pesticide mixtures appear to have a cumulative toxic effect on frogs. Tadpoles from ponds containing multiple pesticides take longer to metamorphose and are smaller when they do, decreasing their ability to catch prey and avoid predators. Exposing tadpoles to the organochloride endosulfan

at levels likely to be found in habitats near fields sprayed with the

chemical kills the tadpoles and causes behavioral and growth

abnormalities.

The herbicide atrazine can turn male frogs into hermaphrodites, decreasing their ability to reproduce. Both reproductive and nonreproductive effects in aquatic reptiles and amphibians have been reported. Crocodiles, many turtle species and some lizards lack sex-distinct chromosomes until after fertilization during organogenesis, depending on temperature. Embryonic exposure in turtles to various PCBs

causes a sex reversal. Across the United States and Canada disorders

such as decreased hatching success, feminization, skin lesions, and

other developmental abnormalities have been reported.

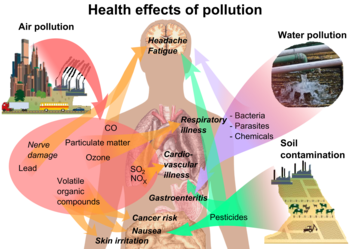

Pesticides are implicated in a range of impacts on human health due to pollution

Humans

Pesticides can enter the body through inhalation of aerosols, dust and vapor that contain pesticides; through oral exposure by consuming food/water; and through skin exposure by direct contact.

Pesticides secrete into soils and groundwater which can end up in

drinking water, and pesticide spray can drift and pollute the air.

The effects of pesticides on human health depend on the toxicity of the chemical and the length and magnitude of exposure.

Farm workers and their families experience the greatest exposure to

agricultural pesticides through direct contact. Every human contains

pesticides in their fat cells.

Children are more susceptible and sensitive to pesticides, because they are still developing and have a weaker immune system

than adults. Children may be more exposed due to their closer proximity

to the ground and tendency to put unfamiliar objects in their mouth.

Hand to mouth contact depends on the child's age, much like lead

exposure. Children under the age of six months are more apt to

experience exposure from breast milk and inhalation of small particles.

Pesticides tracked into the home from family members increase the risk

of exposure. Toxic residue in food may contribute to a child’s exposure. The chemicals can bioaccumulate in the body over time.

Exposure effects can range from mild skin irritation to birth defects, tumors, genetic changes, blood and nerve disorders, endocrine disruption, coma or death.

Developmental effects have been associated with pesticides. Recent

increases in childhood cancers in throughout North America, such as leukemia, may be a result of somatic cell mutations.

Insecticides targeted to disrupt insects can have harmful effects on

mammalian nervous systems. Both chronic and acute alterations have been

observed in exposees. DDT and its breakdown product DDE disturb

estrogenic activity and possibly lead to breast cancer. Fetal DDT exposure reduces male penis size in animals and can produce undescended testicles.

Pesticide can affect fetuses in early stages of development, in utero

and even if a parent was exposed before conception. Reproductive

disruption has the potential to occur by chemical reactivity and through

structural changes.

Persistent organic pollutants

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are compounds that resist degradation and thus remain in the environment for years. Some pesticides, including aldrin, chlordane, DDT, dieldrin, endrin, heptachlor, hexachlorobenzene, mirex and toxaphene,

are considered POPs. Some POPs have the ability to volatilize and

travel great distances through the atmosphere to become deposited in

remote regions. Such chemicals may have the ability to bioaccumulate and biomagnify and can bioconcentrate (i.e. become more concentrated) up to 70,000 times their original concentrations. POPs can affect non-target organisms in the environment and increase risk to humans by disruption in the endocrine, reproductive, and respiratory systems.

Pest resistance

Pests may evolve

to become resistant to pesticides. Many pests will initially be very

susceptible to pesticides, but following mutations in their genetic

makeup become resistant and survive to reproduce.

Resistance is commonly managed through pesticide rotation, which involves alternating among pesticide classes with different modes of action to delay the onset of or mitigate existing pest resistance.

Pest rebound and secondary pest outbreaks

Non-target organisms can also be impacted by pesticides. In some cases, a pest insect that is controlled by a beneficial predator or parasite can flourish should an insecticide application kill both pest and beneficial populations. A study comparing biological pest control and pyrethroid insecticide for diamondback moths, a major cabbage family insect pest, showed that the pest population rebounded due to loss of insect predators, whereas the biocontrol did not show the same effect. Likewise, pesticides sprayed to control mosquitoes

may temporarily depress mosquito populations, they may result in a

larger population in the long run by damaging natural controls.

This phenomenon, wherein the population of a pest species rebounds to

equal or greater numbers than it had before pesticide use, is called

pest resurgence and can be linked to elimination of its predators and

other natural enemies.

Loss of predator species can also lead to a related phenomenon

called secondary pest outbreaks, an increase in problems from species

that were not originally a problem due to loss of their predators or

parasites.

An estimated third of the 300 most damaging insects in the US were

originally secondary pests and only became a major problem after the use

of pesticides.

In both pest resurgence and secondary outbreaks, their natural enemies

were more susceptible to the pesticides than the pests themselves, in

some cases causing the pest population to be higher than it was before

the use of pesticide.

Eliminating pesticides

Many

alternatives are available to reduce the effects pesticides have on the

environment. Alternatives include manual removal, applying heat,

covering weeds with plastic, placing traps and lures, removing pest

breeding sites, maintaining healthy soils that breed healthy, more

resistant plants, cropping native species that are naturally more

resistant to native pests and supporting biocontrol agents such as birds

and other pest predators.

In the United States, conventional pesticide use peaked in 1979, and

by 2007, had been reduced by 25 percent from the 1979 peak level, while US agricultural output increased by 43 percent over the same period.

Biological controls such as resistant plant varieties and the use of pheromones, have been successful and at times permanently resolve a pest problem. Integrated Pest Management

(IPM) employs chemical use only when other alternatives are

ineffective. IPM causes less harm to humans and the environment. The

focus is broader than on a specific pest, considering a range of pest

control alternatives. Biotechnology can also be an innovative way to control pests. Strains can be genetically modified (GM) to increase their resistance to pests. The same techniques can be used to increase pesticide resistance and was employed by Monsanto to create glyphosate-resistant strains of major crops. In the United States in 2010, 70% of all the corn that was planted was resistant to glyphosate; 78% of cotton, and 93% of all soybeans.