Seawater in the Strait of Malacca

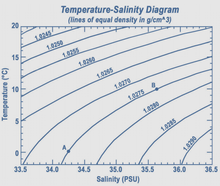

Temperature-salinity diagram of changes in density of water

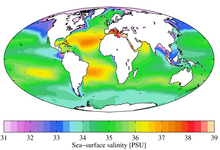

Ocean salinity at different latitudes in the Atlantic and Pacific

Seawater, or salt water, is water from a sea or ocean. On average, seawater in the world's oceans has a salinity

of about 3.5% (35 g/L, 599 mM). This means that every kilogram (roughly

one litre by volume) of seawater has approximately 35 grams (1.2 oz) of

dissolved salts (predominantly sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl−) ions). Average density at the surface is 1.025 kg/L. Seawater is denser than both fresh water

and pure water (density 1.0 kg/L at 4 °C (39 °F)) because the dissolved

salts increase the mass by a larger proportion than the volume. The freezing point of seawater decreases as salt concentration increases. At typical salinity, it freezes at about −2 °C (28 °F). The coldest seawater ever recorded (in a liquid state) was in 2010, in a stream under an Antarctic glacier, and measured −2.6 °C (27.3 °F). Seawater pH is typically limited to a range between 7.5 and 8.4.

However, there is no universally accepted reference pH-scale for

seawater and the difference between measurements based on different

reference scales may be up to 0.14 units.

Geochemistry

Salinity

Annual mean sea surface salinity expressed in the Practical Salinity Scale for the World Ocean. Data from the World Ocean Atlas

Although the vast majority of seawater has a salinity of between 31

g/kg and 38 g/kg, that is 3.1–3.8%, seawater is not uniformly saline

throughout the world. Where mixing occurs with fresh water runoff from

river mouths, near melting glaciers or vast amounts of precipitation

(e.g. Monsoon), seawater can be substantially less saline. The most saline open sea is the Red Sea, where high rates of evaporation, low precipitation

and low river run-off, and confined circulation result in unusually

salty water. The salinity in isolated bodies of water can be

considerably greater still - about ten times higher in the case of the Dead Sea.

Historically, several salinity scales were used to approximate the

absolute salinity of seawater. A popular scale was the "Practical

Salinity Scale" where salinity was measured in "practical salinity units

(psu)". The current standard for salinity is the "Reference Salinity"

scale with the salinity expressed in units of "g/kg".

Thermophysical properties of seawater

The density of surface seawater ranges from about 1020 to 1029 kg/m3,

depending on the temperature and salinity. At a temperature of 25 °C,

salinity of 35 g/kg and 1 atm pressure, the density of seawater is

1023.6 kg/m3. Deep in the ocean, under high pressure, seawater can reach a density of 1050 kg/m3

or higher. The density of seawater also changes with salinity. Brines

generated by seawater desalination plants can have salinities up to 120

g/kg. The density of typical seawater brine of 120 g/kg salinity at

25 °C and atmospheric pressure is 1088 kg/m3. Seawater pH is limited to the range 7.5 to 8.4. The speed of sound

in seawater is about 1,500 m/s (whereas speed of sound is usually

around 330 m/s in air at roughly 1000hPa pressure, 1 atmosphere), and

varies with water temperature, salinity, and pressure. The thermal conductivity of seawater is 0.6 W/mK at 25 °C and a salinity of 35 g/kg.

The thermal conductivity decreases with increasing salinity and increases with increasing temperature.

Chemical composition

Seawater contains more dissolved ions than all types of freshwater. However, the ratios of solutes differ dramatically. For instance, although seawater contains about 2.8 times more bicarbonate than river water, the percentage of bicarbonate in seawater as a ratio of all dissolved ions is far lower than in river water. Bicarbonate ions constitute 48% of river water solutes but only 0.14% for seawater. Differences like these are due to the varying residence times of seawater solutes; sodium and chloride have very long residence times, while calcium (vital for carbonate formation) tends to precipitate much more quickly. The most abundant dissolved ions in seawater are sodium, chloride, magnesium, sulfate and calcium. Its osmolarity is about 1000 mOsm/l.

Small amounts of other substances are found, including amino acids at concentrations of up to 2 micrograms of nitrogen atoms per liter, which are thought to have played a key role in the origin of life.

Diagram showing concentrations of various salt ions in seawater. The composition of the total salt component is: Cl− 55%, Na+ 30.6%, SO2−

4 7.7%, Mg2+ 3.7%, Ca2+ 1.2%, K+ 1.1%, Other 0.7%. Note that the diagram is only correct when in units of wt/wt, not wt/vol or vol/vol.

4 7.7%, Mg2+ 3.7%, Ca2+ 1.2%, K+ 1.1%, Other 0.7%. Note that the diagram is only correct when in units of wt/wt, not wt/vol or vol/vol.

| Element | Percent by mass |

|---|---|

| Oxygen | 85.84 |

| Hydrogen | 10.82 |

| Chlorine | 1.94 |

| Sodium | 1.08 |

| Magnesium | 0.1292 |

| Sulfur | 0.091 |

| Calcium | 0.04 |

| Potassium | 0.04 |

| Bromine | 0.0067 |

| Carbon | 0.0028 |

| Vanadium | 1.5 × 10−11 – 3.3 × 10−11 |

| Component | Concentration (mol/kg) |

|---|---|

| H 2O |

53.6 |

| Cl− | 0.546 |

| Na+ | 0.469 |

| Mg2+ | 0.0528 |

| SO2− 4 |

0.0282 |

| Ca2+ | 0.0103 |

| K+ | 0.0102 |

| CT | 0.00206 |

| Br− | 0.000844 |

| BT | 0.000416 |

| Sr2+ | 0.000091 |

| F− | 0.000068 |

Microbial components

Research in 1957 by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography sampled water in both pelagic and neritic

locations in the Pacific Ocean. Direct microscopic counts and cultures

were used, the direct counts in some cases showing up to 10 000 times

that obtained from cultures. These differences were attributed to the

occurrence of bacteria in aggregates, selective effects of the culture

media, and the presence of inactive cells. A marked reduction in

bacterial culture numbers was noted below the thermocline, but not by direct microscopic observation. Large numbers of spirilli-like

forms were seen by microscope but not under cultivation. The disparity

in numbers obtained by the two methods is well known in this and other

fields. In the 1990s, improved techniques of detection and identification of microbes by probing just small snippets of DNA, enabled researchers taking part in the Census of Marine Life

to identify thousands of previously unknown microbes usually present

only in small numbers. This revealed a far greater diversity than

previously suspected, so that a litre of seawater may hold more than

20,000 species. Mitchell Sogin from the Marine Biological Laboratory feels that "the number of different kinds of bacteria in the oceans could eclipse five to 10 million."

Bacteria are found at all depths in the water column, as well as in the sediments, some being aerobic, others anaerobic. Most are free-swimming, but some exist as symbionts within other organisms – examples of these being bioluminescent bacteria. Cyanobacteria played an important role in the evolution of ocean processes, enabling the development of stromatolites and oxygen in the atmosphere.

Some bacteria interact with diatoms, and form a critical link in the cycling of silicon in the ocean. One anaerobic species, Thiomargarita namibiensis, plays an important part in the breakdown of hydrogen sulfide eruptions from diatomaceous sediments off the Namibian coast, and generated by high rates of phytoplankton growth in the Benguela Current upwelling zone, eventually falling to the seafloor.

Bacteria-like Archaea surprised marine microbiologists by their survival and thriving in extreme environments, such as the hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor. Alkalotolerant marine bacteria such as Pseudomonas and Vibrio spp. survive in a pH range of 7.3 to 10.6, while some species will grow only at pH 10 to 10.6. Archaea also exist in pelagic waters and may constitute as much as half the ocean's biomass, clearly playing an important part in oceanic processes. In 2000 sediments from the ocean floor revealed a species of Archaea that breaks down methane, an important greenhouse gas and a major contributor to atmospheric warming.

Some bacteria break down the rocks of the sea floor, influencing

seawater chemistry. Oil spills, and runoff containing human sewage and

chemical pollutants have a marked effect on microbial life in the

vicinity, as well as harbouring pathogens and toxins affecting all forms

of marine life. The protist dinoflagellates may at certain times undergo population explosions called blooms or red tides, often after human-caused pollution. The process may produce metabolites known as biotoxins, which move along the ocean food chain, tainting higher-order animal consumers.

Pandoravirus salinus,

a species of very large virus, with a genome much larger than that of

any other virus species, was discovered in 2013. Like the other very

large viruses Mimivirus and Megavirus, Pandoravirus infects amoebas, but its genome, containing 1.9 to 2.5 megabases of DNA, is twice as large as that of Megavirus, and it differs greatly from the other large viruses in appearance and in genome structure.

In 2013 researchers from Aberdeen University

announced that they were starting a hunt for undiscovered chemicals in

organisms that have evolved in deep sea trenches, hoping to find "the

next generation" of antibiotics, anticipating an "antibiotic apocalypse"

with a dearth of new infection-fighting drugs. The EU-funded research

will start in the Atacama Trench and then move on to search trenches off New Zealand and Antarctica.

The ocean has a long history of human waste disposal on the

assumption that its vast size makes it capable of absorbing and diluting

all noxious material.

While this may be true on a small scale, the large amounts of sewage

routinely dumped has damaged many coastal ecosystems, and rendered them

life-threatening. Pathogenic viruses and bacteria occur in such waters,

such as Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholerae the cause of cholera, hepatitis A, hepatitis E and polio, along with protozoans causing giardiasis and cryptosporidiosis.

These pathogens are routinely present in the ballast water of large

vessels, and are widely spread when the ballast is discharged.

Origin

Scientific theories behind the origins of sea salt started with Sir Edmond Halley

in 1715, who proposed that salt and other minerals were carried into

the sea by rivers after rainfall washed it out of the ground. Upon

reaching the ocean, these salts concentrated as more salt arrived over

time. Halley noted that most lakes that don't have ocean outlets (such as the Dead Sea and the Caspian Sea, see endorheic basin), have high salt content. Halley termed this process "continental weathering".

Halley's theory was partly correct. In addition, sodium leached

out of the ocean floor when the ocean formed. The presence of salt's

other dominant ion, chloride, results from outgassing of chloride (as hydrochloric acid) with other gases from Earth's interior via volcanos and hydrothermal vents. The sodium and chloride ions subsequently became the most abundant constituents of sea salt.

Ocean salinity has been stable for billions of years, most likely as a consequence of a chemical/tectonic system which removes as much salt as is deposited; for instance, sodium and chloride sinks include evaporite deposits, pore-water burial, and reactions with seafloor basalts.

Human impacts

Climate change, rising atmospheric carbon dioxide,

excess nutrients, and pollution in many forms are altering global

oceanic geochemistry. Rates of change for some aspects greatly exceed

those in the historical and recent geological record. Major trends

include an increasing acidity, reduced subsurface oxygen in both near-shore and pelagic waters, rising coastal nitrogen levels, and widespread increases in mercury

and persistent organic pollutants. Most of these perturbations are tied

either directly or indirectly to human fossil fuel combustion,

fertilizer, and industrial activity. Concentrations are projected to

grow in coming decades, with negative impacts on ocean biota and other

marine resources.

One of the most striking features of this is ocean acidification, resulting from increased CO2 uptake of the oceans related to higher atmospheric concentration of CO2 and higher temperatures, because it severely affects coral reefs and crustaceans.

Human consumption

Accidentally consuming small quantities of clean seawater is not

harmful, especially if the seawater is taken along with a larger

quantity of fresh water. However, drinking seawater to maintain

hydration is counterproductive; more water must be excreted to eliminate

the salt (via urine) than the amount of water obtained from the seawater itself.

The renal system actively regulates sodium chloride in the blood within a very narrow range around 9 g/L (0.9% by weight).

In most open waters concentrations vary somewhat around typical

values of about 3.5%, far higher than the body can tolerate and most

beyond what the kidney can process. A point frequently overlooked in

claims that the kidney can excrete NaCl in Baltic concentrations of 2%

(in arguments to the contrary) is that the gut cannot absorb water at

such concentrations, so that there is no benefit in drinking such water.

Drinking seawater temporarily increases blood's NaCl concentration.

This signals the kidney

to excrete sodium, but seawater's sodium concentration is above the

kidney's maximum concentrating ability. Eventually the blood's sodium

concentration rises to toxic levels, removing water from cells and

interfering with nerve conduction, ultimately producing fatal seizure and cardiac arrhythmia.

Survival manuals consistently advise against drinking seawater. A summary of 163 life raft

voyages estimated the risk of death at 39% for those who drank

seawater, compared to 3% for those who did not. The effect of seawater

intake on rats confirmed the negative effects of drinking seawater when

dehydrated.

The temptation to drink seawater was greatest for sailors who had

expended their supply of fresh water, and were unable to capture enough

rainwater for drinking. This frustration was described famously by a

line from Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner:

-

-

- "Water, water, everywhere,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, everywhere,

Nor any drop to drink."

- "Water, water, everywhere,

-

Although humans cannot survive on seawater, some people claim that up

to two cups a day, mixed with fresh water in a 2:3 ratio, produces no

ill effect. The French physician Alain Bombard

survived an ocean crossing in a small Zodiak rubber boat using mainly

raw fish meat, which contains about 40 percent water (like most living

tissues), as well as small amounts of seawater and other provisions

harvested from the ocean. His findings were challenged, but an

alternative explanation was not given. In his 1948 book, Kon-Tiki, Thor Heyerdahl reported drinking seawater mixed with fresh in a 2:3 ratio during the 1947 expedition. A few years later, another adventurer, William Willis,

claimed to have drunk two cups of seawater and one cup of fresh per day

for 70 days without ill effect when he lost part of his water supply.

During the 18th century, Richard Russell advocated the practice's medical use in the UK, and René Quinton

expanded the advocation of the practice other countries, notably

France, in the 20th century. Currently, the practice is widely used in

Nicaragua and other countries, supposedly taking advantage of the latest

medical discoveries.

Most ocean-going vessels desalinate potable water from seawater using processes such as vacuum distillation or multi-stage flash distillation in an evaporator, or, more recently, reverse osmosis. These energy-intensive processes were not usually available during the Age of Sail. Larger sailing warships with large crews, such as Nelson's HMS Victory, were fitted with distilling apparatus in their galleys.

Animals such as fish, whales, sea turtles, and seabirds, such as penguins and albatrosses

have adapted to living in a high saline habitat. For example, sea

turtles and saltwater crocodiles remove excess salt from their bodies

through their tear ducts.

Standard

ASTM International has an international standard for artificial seawater:

ASTM D1141-98 (Original Standard ASTM D1141-52). It is used in many

research testing labs as a reproducible solution for seawater such as

tests on corrosion, oil contamination, and detergency evaluation.