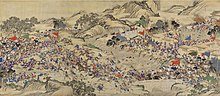

A sample scene of the Taiping Rebellion.

Saladin and Guy of Lusignan after the Battle of Hattin of 1187

A religious war or holy war (Latin: bellum sacrum) is a war primarily caused or justified by differences in religion. In the modern period, debates are common over the extent to which religious, economic, or ethnic aspects of a conflict predominate in a given war. According to the Encyclopedia of Wars, out of all 1,763 known/recorded historical conflicts, 123, or 6.98%, had religion as their primary cause. Matthew White's The Great Big Book of Horrible Things gives religion as the cause of 13 of the world's 100 deadliest atrocities. In several conflicts including the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, the Syrian civil war, and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, religious elements are overtly present but variously described as fundamentalism or religious extremism—depending

upon the observer's sympathies. However, studies on these cases often

conclude that ethnic animosities drive much of the conflicts.

Some historians argue that what is termed "religious wars" is a

largely "Western dichotomy" and a modern invention from the past few

centuries, arguing that all wars that are classed as "religious" have

secular (economic or political) ramifications. Similar opinions were expressed as early as the 1760s, during the Seven Years' War,

widely recognized to be "religious" in motivation, noting that the

warring factions were not necessarily split along confessional lines as

much as along secular interests.

According to Jeffrey Burton Russell, numerous cases of supposed acts of religious wars such as the Thirty Years' War, the French Wars of Religion, the Sri Lankan Civil War, 9/11 and other terrorist attacks, the Bosnian War, and the Rwandan Civil War were all primarily motivated by social, political, and economic issues rather than religion. For example, in the Thirty Years' War the dominant participant on the "Protestant" side for much of the conflict was France, led by Cardinal Richelieu.

History of the concept of religion

The modern word religion comes from the Latin word religio. In the ancient and medieval world, the etymological Latin root religio was understood as an individual virtue of worship, never as doctrine, practice, or actual source of knowledge.

The modern concept of "religion" as an abstraction which entails

distinct sets of beliefs or doctrines is a recent invention in the

English language since such usage began with texts from the 17th century

due to the splitting of Christendom during the Protestant Reformation

and more prevalent colonization or globalization in the age of

exploration which involved contact with numerous foreign and indigenous

cultures with non-European languages.

It was in the 17th century that the concept of "religion" received its

modern shape despite the fact that the Bible, the Quran, and other

ancient sacred texts did not have a concept of religion in the original

languages and neither did the people or the cultures in which these

sacred texts were written. For example, the Greek word threskeia,

which was used by Greek writers such as Herodotus and Josephus and is

found in texts like the New Testament, is sometimes translated as

"religion" today, however, the term was understood as "worship" well

into the medieval period.

In the Quran, the Arabic word din is often translated as "religion" in modern translations, but up to the mid-1600s translators expressed din as "law". Even in the 1st century AD, Josephus had used the Greek term ioudaismos,

which some translate as "Judaism" today, even though he used it as an

ethnic term, not one linked to modern abstract concepts of religion as a

set of beliefs. It was in the 19th century that the terms "Buddhism", "Hinduism", "Taoism", and "Confucianism" first emerged.

Throughout its long history, Japan had no concept of "religion" since

there was no corresponding Japanese word, nor anything close to its

meaning, but when American warships appeared off the coast of Japan in

1853 and forced the Japanese government to sign treaties demanding,

among other things, freedom of religion, the country had to contend with

this Western idea.

According to the philologist Max Müller in the 19th century, the root of the English word "religion", the Latin religio, was originally used to mean only "reverence for God or the gods, careful pondering of divine things, piety" (which Cicero further derived to mean "diligence"). Max Müller

characterized many other cultures around the world, including Egypt,

Persia, and India, as having a similar power structure at this point in

history. What is called ancient religion today, they would have only

called "law".

Some languages have words that can be translated as "religion",

but they may use them in a very different way, and some have no word for

religion at all. For example, the Sanskrit word dharma, sometimes translated as "religion", also means law. Throughout classical South Asia, the study of law consisted of concepts such as penance through piety and ceremonial as well as practical traditions.

Medieval Japan at first had a similar union between "imperial law" and

universal or "Buddha law", but these later became independent sources of

power.

There is no precise equivalent of "religion" in Hebrew, and Judaism does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities.

One of its central concepts is "halakha", meaning the "walk" or "path"

sometimes translated as "law", which guides religious practice and

belief and many aspects of daily life.

Criteria for classification

The Crusades against Muslim expansion in the 11th century was recognized as a "holy war" or bellum sacrum by later writers in the 17th century. The early modern wars against the Ottoman Empire were seen as a seamless continuation of this conflict by contemporaries.

The term "religious war" was used to describe, controversially at the time, what are now known as the European wars of religion, and especially the then-ongoing Seven Years' War, from at least the mid 18th century.

In their Encyclopedia of Wars, authors Charles Phillips and Alan Axelrod document 1763 notable wars in world history out of which 121 wars are in the "religious wars" category in the index.

They note that before the 17th century, much of the "reasons" for

conflicts were explained through the lens of religion and that after

that time wars were explained through the lens of wars as a way to

further sovereign interests.

Some commentators have concluded that only 123 wars (7%) out of these

1763 wars were fundamentally originated by religious motivations.

The Encyclopedia of War, edited by Gordon Martel, using

the criteria that the armed conflict must involve some overt religious

action, concludes that 6% of the wars listed in their encyclopedia can

be labelled religious wars.

William T. Cavanaugh in his Myth of Religious Violence

(2009) argues that what is termed "religious wars" is a largely

"Western dichotomy" and a modern invention, arguing that all wars that

are classed as "religious" have secular (economic or political)

ramifications. Similar opinions were expressed as early as the 1760s, during the Seven Years' War,

widely recognized to be "religious" in motivation, noting that the

warring factions were not necessarily split along confessional lines as

much as along secular interests.

It is evident that religion as one aspect of a people's cultural heritage

may serve as a cultural marker or ideological rationalisation for a

conflict that has deeper ethnic and cultural differences. This has been

specifically argued for the case of The Troubles in Northern Ireland,

often portrayed as a religious conflict of a Catholic vs. a Protestant

faction, while the more fundamental cause of the conflict was in fact

ethnic or nationalistic rather than religious in nature.

Since the native Irish were mostly Catholic and the later

British-sponsored immigrants were mainly Protestant, the terms become

shorthand for the two cultures, but it is inaccurate to describe the

conflict as a religious one.

According to Irfan Omar and Michael Duffey's review of violence

and peacemaking in world religions, they note that studies of supposed

cases of religious violence often conclude that violence is strongly

driven by ethnic animosities.

The concept of "Holy War" in individual religious traditions

While early empires could be described as henotheistic, i.e. dominated by a single god of the ruling elite (as Marduk in the Babylonian empire, Assur in the Assyrian empire, etc.), or more directly by deifing the ruler in an imperial cult, the concept of "Holy War" enters a new phase with the development of monotheism.

Ancient warfare and polytheism

Classical Antiquity had a pantheon with particular attributes and interest areas. Ares personified war. While he received occasional sacrifice from armies going to war, there was only a very limited "cult of Ares". In Sparta, however, each company of youths sacrificed to Enyalios before engaging in ritual fighting at the Phoebaeum.

Christianity

The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre of French Protestants, 1572

In early Christianity, St. Augustine's concept of just war (bellum iustum) was widely accepted, but warfare was not regarded as a virtuous activity

and expressions of concern for the salvation of those who killed

enemies in battle, regardless of the cause for which they fought, was

common. According to historian Edward Peters, before the 11th century Christians had not developed a concept of "Holy War" (bellum sacrum), whereby fighting itself might be considered a penitential and spiritually meritorious act.

During the 9th and 10th centuries, multiple invasions occurred which

lead some regions to make their own armies to defend themselves and this

slowly lead to the emergence of the Crusades, the concept of "holy

war", and terminology such as "enemies of God" in the 11th century.

During the time of the Crusades, some of those who fought in the name of God were recognized as the Milites Christi, soldiers or knights of Christ.

The Crusades were a series of military campaigns that took place during the 11th through 13th centuries against the Muslim Conquests. Originally, the goal was to recapture Jerusalem and the Holy Land from the Muslims, and support the besieged Christian Byzantine Empire against the Muslim Seljuq

expansion into Asia Minor and Europe proper. Later, Crusades were

launched against other targets, either for religious reasons, such as

the Albigensian Crusade, the Northern Crusades, or because of political conflict, such as the Aragonese Crusade. In 1095, at the Council of Clermont, Pope Urban II raised the level of war from bellum iustum ("just war"), to bellum sacrum ("holy war"). In 16th-century France there was a succession of wars between Roman Catholics and Protestants (Hugenots primarily), known as the French Wars of Religion. In the first half of the 17th century, the German states, Scandinavia (Sweden, primarily) and Poland were beset by religious warfare in the Thirty Years War. Roman Catholicism and Protestantism figured in the opposing sides of this conflict, though Catholic France did take the side of the Protestants but purely for political reasons.

The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa,

known in Arab history as the Battle of Al-Uqab (معركة العقاب), took

place on 16 July 1212 and was an important turning point in the Reconquista and in the medieval history of Spain. The forces of King Alfonso VIII of Castile were joined by the armies of his Christian rivals, Sancho VII of Navarre, Pedro II of Aragon and Afonso II of Portugal in battle against the Berber Muslim Almohad conquerors of the southern half of the Iberian Peninsula.

Islam

The Muslim conquests were a military expansion on an unprecedented scale, beginning in the lifetime of Muhammad and spanning the centuries, down to the Ottoman wars in Europe. Until the 13th century, the Muslim conquests were those of a more or less coherent empire, the Caliphate, but after the Mongol invasions, expansion continued on all fronts (other than Iberia which was lost in the Reconquista) for another half millennium until the final collapse of the Mughal Empire in the east and the Ottoman Empire in the west with the onset of the modern period.

There were also a number of periods of infighting among Muslims; these are known by the term Fitna

and mostly concern the early period of Islam, from the 7th to 11th

centuries, i.e. before the collapse of the Caliphate and the emergence

of the various later Islamic empires.

While technically, the millennium of Muslim conquests could be

classified as "religious war", the applicability of the term has been

questioned.

The reason is that the very notion of a "religious war" as opposed to a

"secular war" is the result of the Western concept of the separation of Church and State.

No such division has ever existed in the Islamic world, and

consequently there cannot be a real division between wars that are

"religious" from such that are "non-religious". Islam does not have any

normative tradition of pacifism,

and warfare has been integral part of Islamic history both for the

defense and the spread of the faith since the time of Muhammad. This was

formalised in the juristic definition of war in Islam,

which continues to hold normative power in contemporary Islam,

inextricably linking political and religious justification of war. This normative concept is known as Jihad,

an Arabic word with the meaning "to strive; to struggle" (viz. "in the

way of God"), which includes the aspect of struggle "by the sword".

The first forms of military Jihad occurred after the migration (hijra) of Muhammad and his small group of followers to Medina from Mecca

and the conversion of several inhabitants of the city to Islam. The

first revelation concerning the struggle against the Meccans was surah

22, verses 39-40:

To those against whom war is made, permission is given (to fight), because they are wronged;- and verily, Allah is most powerful for their aid. (They are) those who have been expelled from their homes in defiance of right,- (for no cause) except that they say, "our Lord is Allah". Did not Allah check one set of people by means of another, there would surely have been pulled down monasteries, churches, synagogues, and mosques, in which the name of Allah is commemorated in abundant measure. Allah will certainly aid those who aid his (cause);- for verily Allah is full of Strength, Exalted in Might, (able to enforce His Will).

— Abdullah Yusuf Ali

This happened many times throughout history, beginning with Muhammad's battles against the polytheist Arabs including the Battle of Badr (624), and battles in Uhud (625), Khandaq (627), Mecca (630) and Hunayn (630).

Judaism

In the Jewish religion, the expression Milkhemet Mitzvah (Hebrew: מלחמת מצווה, "commandment war") refers to a war that is obligatory for all Jews (men and women). Such wars were limited to territory within the borders of the land of Israel. The geographical limits of Israel and conflicts with surrounding nations are detailed in the Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible,

especially in Numbers 34:1-15 and Ezekiel 47:13-20. The concept of a

religious war was absent in Jewish thought for approximately 2000 years,

though it reemerged in some factions of the Zionist movement, particularly Revisionist Zionism.

"From the earliest days of Israel's existence as a people, holy war was

a sacred institution, undertaken as a cultic act of a religious

community.

According to Reuven Firestone, ""Holy War" is a Western concept

referring to war that is fought for religion, against adherents of other

religions, often in order to promote religion through conversion, and

with no specific geographic limitation. This concept does not occur in

the Hebrew Bible, whose wars are not fought for religion or in order to

promote it but, rather, in order to preserve religion and a religiously

unique people in relation to a specific and limited geography."

Religious conflict in the modern period

Israeli–Palestinian conflict

Demolished home in Balata, 2002, Second Intifada

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict can be viewed primarily as an ethnic conflict

between two parties where one party is most often portrayed as a

singular ethno-religious group consisting only of the Jewish majority

and ignores non-Jewish minority Israeli citizens who at varying levels

support a Zionist state, especially the Druze and Circassians who for example volunteer in higher numbers for IDF combat service and are represented in the Israeli parliament in greater percentages than Israeli Jews are as well as Israeli Arabs, Samaritans, various other Christians, and Negev Bedouin;

the other party is sometimes presented as an ethnic group which is

multi-religious (although most numerously consisting of Muslims, then

Christians, then other religious groups up to and including Samaritans

and even Jews). Yet despite the multi-religious composition of both of

the parties in the conflict, elements on both sides often view it as a

religious war between Jews and Muslims. In 1929, religious tensions

between Muslim and Jewish Palestinians over Jews praying at the Wailing Wall led to the 1929 Palestine riots including the Hebron and Safed ethnic cleansings of Jews.

In 1947, the UN decided on partitioning the Mandate of Palestine, led to the creation of the state of Israel and Jordan annexing the West Bank portion of the mandate, since then the region has been plagued with conflict. The 1948 Palestinian exodus also known as the Nakba (Arabic: النكبة), occurred when approximately 711,000 to 726,000 Palestinian Arabs fled or were expelled from their homes, during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War and the Civil War that preceded it.

The exact number of refugees is a matter of dispute, though the number

of Palestine refugees and their unsettled descendants registered with

UNRWA is more than 4.3 million.

The causes remain the subject of fundamental disagreement between

Palestinians and Israelis. Jews make a religious and historical claim to

the land, and Palestinians make historic, religious and ethnic claims

to the land.

Pakistan and India

The All India Muslim League (AIML) was formed in Dhaka in 1906 by Muslims who were suspicious of the Hindu-majority Indian National Congress.

They complained that Muslim members did not have the same rights as

Hindu members. A number of different scenarios were proposed at various

times.This was fuelled by the British policy of "Divide and Rule", which

they tried to bring upon every political situation. Among the first to

make the demand for a separate state was the writer/philosopher Allama Iqbal,

who, in his presidential address to the 1930 convention of the Muslim

League said that a separate nation for Muslims was essential in an

otherwise Hindu-dominated subcontinent.

After the dissolution of the British Raj in 1947, two new sovereign nations were formed—the Union of India and the Dominion of Pakistan. The subsequent partition of the former British India displaced up to 12.5 million people, with estimates of loss of life varying from several hundred thousand to a million. India emerged as a secular nation with a Hindu majority, while Pakistan was established as an Islamic republic with Muslim majority population.

Abyssinia – Somalia

Abyssinian–Adal war broke out in the Horn of Africa after the arrival of the Portuguese Empire in the region.

The Abyssinian–Adal war was a military conflict between the Abyssinians and the Adal Sultanate from 1529 until 1559. The Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (nicknamed Gurey in Somali and Gragn in Amharic (ግራኝ Graññ),

both meaning "the left-handed") came close to extinguishing the ancient

realm of Abyssinia, and forcibly converting all of its surviving

subjects to Islam; the intervention of the European Cristóvão da Gama, son of the famous navigator Vasco da Gama,

attempted to help to prevent this outcome but was killed by al-Ghazi.

However, both polities exhausted their resources and manpower in this

conflict, allowing the northward migration of the Oromo into their present homelands to the north and west of Addis Ababa. Many historians trace the origins of hostility between Somalia and Ethiopia to this war. Some historians also argue that this conflict proved, through their use on both sides, the value of firearms such as the matchlock musket, cannons, and the arquebus over traditional weapons.

Nigerian conflict

Inter-ethnic

conflict in Nigeria has generally had a religious element. Riots

against Igbo in 1953 and in the 1960s in the north were said to have

been sparked by religious conflict. The riots against Igbo in the north

in 1966 were said to have been inspired by radio reports of mistreatment

of Muslims in the south.

A military coup d'état led by lower and middle-ranking officers, some

of them Igbo, overthrew the NPC-NCNC dominated government. Prime

Minister Balewa along with other northern and western government

officials were assassinated during the coup. The coup was considered an

Igbo plot to overthrow the northern dominated government. A counter-coup

was launched by mostly northern troops. Between June and July there was

a mass exodus of Ibo from the north and west. Over 1.3 million Ibo fled

the neighboring regions in order to escape persecution as anti-Ibo

riots increased. The aftermath of the anti-Ibo riots led many to believe

that security could only be gained by separating from the North.

In the 1980s, serious outbreaks between Christians and Muslims occurred in Kafanchan in southern Kaduna State in a border area between the two religions.

The 2010 Jos riots saw clashes between Muslim herders against Christian farmers near the volatile city of Jos, resulting in hundreds of casualties. Officials estimated that 500 people were massacred in night-time raids by rampaging Muslim gangs.

Buddhist uprising

During the rule of the Catholic Ngo Dinh Diem in South Vietnam,

the discrimination against the majority Buddhist population generated

the growth of Buddhist institutions as they sought to participate in

national politics and gain better treatment. The Buddhist Uprising of 1966 was a period of civil and military unrest in South Vietnam, largely focused in the I Corps area in the north of the country in central Vietnam.

In a country where the Buddhist majority was estimated to be between 70 and 90 percent, Diem ruled with a strong religious bias. As a member of the Catholic Vietnamese minority, he pursued pro-Catholic policies that antagonized many Buddhists.

Chinese conflict

The Dungan revolt (1862–1877) and Panthay Rebellion (1856–1873) by the Hui

were also set off by racial antagonism and class warfare, rather than

the mistaken assumption that it was all due to Islam that the rebellions

broke out. During the Dungan revolt fighting broke out between Uyghurs and Hui.

In 1936, after Sheng Shicai expelled 20,000 Kazakhs from Xinjiang to Qinghai, the Hui led by General Ma Bufang massacred their fellow Muslims, the Kazakhs, until there were only 135 of them left.

Tensions with Uyghurs and Hui arose because Qing and Republican

Chinese authorities used Hui troops and officials to dominate the

Uyghurs and crush Uyghur revolts.

Xinjiang's Hui population increased by over 520 percent between 1940

and 1982, an average annual growth rate of 4.4 percent, while the Uyghur

population only grew by 1.7 percent. This dramatic increase in the Hui

population led inevitably to significant tensions between the Hui and

Uyghur Muslim populations. Some old Uyghurs in Kashgar remember that the Hui army at the Battle of Kashgar (1934) massacred 2,000 to 8,000 Uyghurs, which caused tension as more Hui moved into Kashgar from other parts of China. Some Hui criticize Uyghur separatism, and generally do not want to get involved in conflicts in other countries over Islam for fear of being perceived as radical. Hui and Uyghur live apart from each other, praying separately and attending different mosques.

Lebanese Civil War

War-damaged buildings in Beirut

There is no consensus among scholars on what triggered the Lebanese Civil War. However, the militarization of the Palestinian refugee population, with the arrival of the PLO guerrilla forces did spark an arms race amongst the different Lebanese political factions. However the conflict played out along three religious lines, Sunni Muslim, Christian Lebanese and Shiite Muslim, Druze are considered among Shiite Muslims.

It has been argued that the antecedents of the war can be traced

back to the conflicts and political compromises reached after the end of

Lebanon's administration by the Ottoman Empire. The Cold War had a powerful disintegrative effect on Lebanon, which was closely linked to the polarization that preceded the 1958 political crisis. During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War an exodus of Palestinian refugees who fled the fighting or were expelled from their homes,

arrived in Lebanon. Palestinians came to play a very important role in

future Lebanese civil conflicts, whilst the establishment of Israel

radically changed the local environment in which Lebanon found itself.

Lebanon was promised independence and on 22 November 1943 it was achieved. Free French troops, who had invaded Lebanon in 1941 to rid Beirut of the Vichy French

forces, left the country in 1946. The Christians assumed power over the

country and economy. A confessional parliament was created, where

Muslims and Christians were given quotas of seats in parliament. As

well, the President was to be a Christian, the Prime Minister a Sunni

Muslim and the Speaker of Parliament a Shia Muslim.

In March 1991, parliament passed an amnesty law

that pardoned all political crimes prior to its enactment. The amnesty

was not extended to crimes perpetrated against foreign diplomats or

certain crimes referred by the cabinet to the Higher Judicial Council.

In May 1991, the militias (with the important exception of Hezbollah) were dissolved, and the Lebanese Armed Forces began to slowly rebuild themselves as Lebanon's only major non-sectarian institution.

Some violence still occurred. In late December 1991 a car bomb

(estimated to carry 220 pounds of TNT) exploded in the Muslim

neighborhood of Basta. At least thirty people were killed, and 120 wounded, including former Prime Minister Shafik Wazzan, who was riding in a bulletproof car.

Yugoslav Wars

The Croatian War (1991–95) and Bosnian War (1992–95), have been viewed of as religious wars between the Orthodox, Catholic and Muslim populations of former Yugoslavia, that is, Serbs, Croats and Bosniaks. Traditional religious symbols were used during the wars. Notably, foreign Muslim volunteers came to Bosnia to wage jihad ("jihad" doesn’t mean "holy war", it means "struggle"), and were thus known as "Bosnian mujahideen".

Sudanese Civil War

The Second Sudanese Civil War from 1983 to 2005 have describe the conflict as an ethnoreligious

one where the Muslim central government's pursuits to impose sharia law

on non-Muslim southerners led to violence, and eventually to the civil

war. The war resulted in the independence of South Sudan six years after the war ended. Sudan is Muslim and South Sudan is Christian.