Sexual selection creates colourful differences between sexes (sexual dimorphism) in Goldie's bird-of-paradise. Male above; female below. Painting by John Gerrard Keulemans (d.1912)

Sexual

selection is a form of natural selection where one sex prefers a

specific characteristic in an individual of the other sex. Peafowls

exhibit sexual selection, in that, peahens look for peacocks with more

"eyes" on their tail feathers. This results in the peacocks with more

eyes reproducing more, leading to peacocks with more eyes becoming more

common in subsequent generations.

Sexual selection is a mode of natural selection where members of one biological sex choose mates of the other sex to mate

with (intersexual selection), and compete with members of the same sex

for access to members of the opposite sex (intrasexual selection). These

two forms of selection mean that some individuals have better reproductive success than others within a population, either from being more attractive or preferring more attractive partners to produce offspring. For instance, in the breeding season, sexual selection in frogs occurs with the males first gathering at the water's edge and making their mating calls:

croaking. The females then arrive and choose the males with the deepest

croaks and best territories. In general, males benefit from frequent

mating and monopolizing access to a group of fertile females. Females

can have a limited number of offspring and maximize the return on the

energy they invest in reproduction.

The concept was first articulated by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace

who described it as driving species adaptations and that many organisms

had evolved features whose function was deleterious to their individual

survival, and then developed by Ronald Fisher in the early 20th century. Sexual selection can, typically, lead males to extreme efforts to demonstrate their fitness to be chosen by females, producing sexual dimorphism in secondary sexual characteristics, such as the ornate plumage of birds such as birds of paradise and peafowl, or the antlers of deer, or the manes of lions, caused by a positive feedback mechanism known as a Fisherian runaway,

where the passing-on of the desire for a trait in one sex is as

important as having the trait in the other sex in producing the runaway

effect. Although the sexy son hypothesis indicates that females would prefer male offspring, Fisher's principle explains why the sex ratio is 1:1 almost without exception. Sexual selection is also found in plants and fungi.

The maintenance of sexual reproduction in a highly competitive world is one of the major puzzles in biology given that asexual reproduction

can reproduce much more quickly as 50% of offspring are not males,

unable to produce offspring themselves. Many non-exclusive hypotheses

have been proposed,

including the positive impact of an additional form of selection,

sexual selection, on the probability of persistence of a species.

History

Darwin

Sexual selection was first proposed by Charles Darwin in The Origin of Species (1859) and developed in The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex

(1871), as he felt that natural selection alone was unable to account

for certain types of non-survival adaptations. He once wrote to a

colleague that "The sight of a feather in a peacock's tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick!" His work divided sexual selection into male-male competition and female choice.

... depends, not on a struggle for existence, but on a struggle between the males for possession of the females; the result is not death to the unsuccessful competitor, but few or no offspring.

... when the males and females of any animal have the same general habits ... but differ in structure, colour, or ornament, such differences have been mainly caused by sexual selection.

These views were to some extent opposed by Alfred Russel Wallace,

mostly after Darwin's death. He accepted that sexual selection could

occur, but argued that it was a relatively weak form of selection. He

argued that male-male competitions were forms of natural selection, but

that the "drab" peahen's coloration is itself adaptive as camouflage. In his opinion, ascribing mate choice to females was attributing the ability to judge standards of beauty to animals (such as beetles) far too cognitively undeveloped to be capable of aesthetic feeling.

Ronald Fisher

Ronald Fisher, the English statistician and evolutionary biologist developed a number of ideas about sexual selection in his 1930 book The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection including the sexy son hypothesis and Fisher's principle. The Fisherian runaway

describes how sexual selection accelerates the preference for a

specific ornament, causing the preferred trait and female preference for

it to increase together in a positive feedback runaway cycle. In a remark that was not widely understood for another 50 years he said:

... plumage development in the male, and sexual preference for such developments in the female, must thus advance together, and so long as the process is unchecked by severe counterselection, will advance with ever-increasing speed. In the total absence of such checks, it is easy to see that the speed of development will be proportional to the development already attained, which will therefore increase with time exponentially, or in geometric progression. —Ronald Fisher, 1930

This causes a dramatic increase in both the male's conspicuous feature and in female preference for it, resulting in marked sexual dimorphism, until practical physical constraints halt further exaggeration. A positive feedback

loop is created, producing extravagant physical structures in the

non-limiting sex. A classic example of female choice and potential

runaway selection is the long-tailed widowbird.

While males have long tails that are selected for by female choice,

female tastes in tail length are still more extreme with females being

attracted to tails longer than those that naturally occur.

Fisher understood that female preference for long tails may be passed

on genetically, in conjunction with genes for the long tail itself.

Long-tailed widowbird offspring of both sexes inherit both sets of

genes, with females expressing their genetic preference for long tails, and males showing off the coveted long tail itself.

Richard Dawkins presents a non-mathematical explanation of the runaway sexual selection process in his book The Blind Watchmaker.

Females that prefer long tailed males tend to have mothers that chose

long-tailed fathers. As a result, they carry both sets of genes in their

bodies. That is, genes for long tails and for preferring long tails

become linked.

The taste for long tails and tail length itself may therefore become

correlated, tending to increase together. The more tails lengthen, the

more long tails are desired. Any slight initial imbalance between taste

and tails may set off an explosion in tail lengths. Fisher wrote that:

The exponential element, which is the kernel of the thing, arises from the rate of change in hen taste being proportional to the absolute average degree of taste. —Ronald Fisher, 1932

The peacock tail in flight, the classic example of a Fisherian runaway

The female widow bird chooses to mate with the most attractive

long-tailed male so that her progeny, if male, will themselves be

attractive to females of the next generation - thereby fathering many

offspring that carry the female's genes. Since the rate of change in

preference is proportional to the average taste amongst females, and as

females desire to secure the services of the most sexually attractive

males, an additive effect is created that, if unchecked, can yield

exponential increases in a given taste and in the corresponding desired

sexual attribute.

It is important to notice that the conditions of relative stability brought about by these or other means, will be far longer duration than the process in which the ornaments are evolved. In most existing species the runaway process must have been already checked, and we should expect that the more extraordinary developments of sexual plumage are not due like most characters to a long and even course of evolutionary progress, but to sudden spurts of change. —Ronald Fisher, 1930

Since Fisher's initial conceptual model of the 'runaway' process, Russell Lande and Peter O'Donald have provided detailed mathematical proofs that define the circumstances under which runaway sexual selection can take place.

Theory

Reproductive success

Extinct Irish elk (Megaloceros giganteus). These antlers span 2.7 metres (8.9 ft) and have a mass of 40 kg (88 lb).

The reproductive success of an organism is measured by the number of offspring left behind, and their quality or probable fitness.

Sexual preference creates a tendency towards assortative mating or homogamy.

The general conditions of sexual discrimination appear to be (1) the

acceptance of one mate precludes the effective acceptance of alternative

mates, and (2) the rejection of an offer is followed by other offers,

either certainly or at such high chance that the risk of non-occurrence

is smaller than the chance advantage to be gained by selecting a mate.

The conditions determining which sex becomes the more limited resource in intersexual selection have been hypothesized with Bateman's principle,

which states that the sex which invests the most in producing offspring

becomes a limiting resource for which the other sex competes,

illustrated by the greater nutritional investment of an egg in a zygote,

and the limited capacity of females to reproduce; for example, in

humans, a woman can only give birth every ten months, whereas a male can

become a father numerous times in the same period.

Modern interpretation

Male mountain gorilla, a tournament species

The sciences of evolutionary psychology, human behavioural ecology, and sociobiology study the influence of sexual selection in humans.

Darwin's ideas on sexual selection were met with scepticism by

his contemporaries and not considered of great importance in the early

20th century, until in the 1930s biologists decided to include sexual

selection as a mode of natural selection. Only in the 21st century have they become more important in biology. The theory however is generally applicable and analogous to natural selection.

Flour beetle

Tungara frog

Research in 2015 indicates that sexual selection, including mate choice,

"improves population health and protects against extinction, even in

the face of genetic stress from high levels of inbreeding" and

"ultimately dictates who gets to reproduce their genes into the next

generation - so it's a widespread and very powerful evolutionary force."

The study involved the flour beetle over a ten-year period where the only changes were in the intensity of sexual selection.

Another theory, the handicap principle of Amotz Zahavi, Russell Lande and W. D. Hamilton,

holds that the fact that the male is able to survive until and through

the age of reproduction with such a seemingly maladaptive trait is taken

by the female to be a testament to his overall fitness. Such handicaps

might prove he is either free of or resistant to disease,

or that he possesses more speed or a greater physical strength that is

used to combat the troubles brought on by the exaggerated trait.

Zahavi's work spurred a re-examination of the field, which has produced

an ever-accelerating number of theories. In 1984, Hamilton and Marlene Zuk

introduced the "Bright Male" hypothesis, suggesting that male

elaborations might serve as a marker of health, by exaggerating the

effects of disease and deficiency. In 1990, Michael Ryan and A.S. Rand,

working with the tungara frog,

proposed the hypothesis of "Sensory Exploitation", where exaggerated

male traits may provide a sensory stimulation that females find hard to

resist. Subsequently, the theories of the "Gravity Hypothesis" by Jordi

Moya-Larano et al. (2002), invoking a simple biomechanical model to

account for the adaptive value for smaller male spiders of speed in

clmbing vertical surfaces,

and "Chase Away" by Brett Holland and William R. Rice have been added.

In the late 1970s, Janzen and Mary Willson, noting that male flowers are

often larger than female flowers, expanded the field of sexual

selection into plants.

In the past few years, the field has exploded to include other

areas of study, not all of which fit Darwin's definition of sexual

selection. These include cuckoldry, nuptial gifts, sperm competition, infanticide (especially in primates), physical beauty,

mating by subterfuge, species isolation mechanisms, male parental care,

ambiparental care, mate location, polygamy, and homosexual rape in

certain male animals.

Focusing on the effect of sexual conflict, as hypothesized by William Rice, Locke Rowe et Göran Arnvist, Thierry Lodé argues that divergence of interest constitutes a key for evolutionary process. Sexual conflict leads to an antagonistic co-evolution in which one sex tends to control the other, resulting in a tug of war. Besides, the sexual propaganda theory

only argued that mates were opportunistically led, on the basis of

various factors determining the choice such as phenotypic

characteristics, apparent vigour of individuals, strength of mate

signals, trophic resources, territoriality, etc., but and could explain

the maintenance of genetic diversity within populations.

Several workers have brought attention to the fact that

elaborated characters that ought to be costly in one way or another for

their bearers (e.g., the tails of some species of Xiphophorus

fish) do not always appear to have a cost in terms of energetics,

performance or even survival. One possible explanation for the apparent

lack of costs is that "compensatory traits" have evolved in concert with

the sexually selected traits.

Toolkit of natural selection

Protarchaeopteryx - skull based on Incisivosaurus and wings on Caudipteryx

Sexual selection may explain how certain characteristics (such as

feathers) had distinct survival value at an early stage in their

evolution. Geoffrey Miller proposes that sexual selection might have contributed by creating evolutionary modules such as Archaeopteryx feathers as sexual ornaments, at first. The earliest proto-birds such as China's Protarchaeopteryx,

discovered in the early 1990s, had well-developed feathers but no sign

of the top/bottom asymmetry that gives wings lift. Some have suggested

that the feathers served as insulation, helping females incubate their

eggs. But perhaps the feathers served as the kinds of sexual ornaments

still common in most bird species, and especially in birds such as

peacocks and birds-of-paradise

today. If proto-bird courtship displays combined displays of forelimb

feathers with energetic jumps, then the transition from display to

aerodynamic functions could have been relatively smooth.

Sexual selection sometimes generates features that may help cause a species' extinction, as has been suggested for the giant antlers of the Irish elk (Megaloceros giganteus) that became extinct in Pleistocene Europe. However, sexual selection can also do the opposite, driving species divergence - sometimes through elaborate changes in genitalia - such that new species emerge.

Sexual dimorphism

Sex differences directly related to reproduction and serving no direct purpose in courtship are called primary sexual characteristics.

Traits amenable to sexual selection, which give an organism an

advantage over its rivals (such as in courtship) without being directly

involved in reproduction, are called secondary sex characteristics.

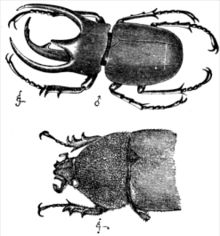

The rhinoceros beetle is a classic case of sexual dimorphism. Plate from Darwin's Descent of Man, male at top, female at bottom

In most sexual species the males and females have different equilibrium

strategies, due to a difference in relative investment in producing

offspring. As formulated in Bateman's principle, females have a greater

initial investment in producing offspring (pregnancy in mammals or the production of the egg in birds and reptiles),

and this difference in initial investment creates differences in

variance in expected reproductive success and bootstraps the sexual

selection processes. Classic examples of reversed sex-role species

include the pipefish, and Wilson's phalarope. Also, unlike a female, a male (except in monogamous

species) has some uncertainty about whether or not he is the true

parent of a child, and so is less interested in spending his energy

helping to raise offspring that may or may not be related to him. As a

result of these factors, males are typically more willing to mate than

females, and so females are typically the ones doing the choosing

(except in cases of forced copulations, which can occur in certain species of primates, ducks, and others). The effects of sexual selection are thus held to typically be more pronounced in males than in females.

Differences in secondary sexual characteristics between males and females of a species are referred to as sexual dimorphisms.

These can be as subtle as a size difference (sexual size dimorphism,

often abbreviated as SSD) or as extreme as horns and colour patterns.

Sexual dimorphisms abound in nature. Examples include the possession of

antlers by only male deer,

the brighter coloration of many male birds in comparison with females

of the same species, or even more distinct differences in basic

morphology, such as the drastically increased eye-span of the male stalk-eyed fly. The peacock, with its elaborate and colourful tail feathers, which the peahen lacks, is often referred to as perhaps the most extraordinary example of a dimorphism. Male and female black-throated blue warblers and Guianan cock-of-the-rocks

also differ radically in their plumage. Early naturalists even believed

the females to be a separate species. The largest sexual size

dimorphism in vertebrates is the shell dwelling cichlid fish Neolamprologus callipterus in which males are up to 30 times the size of females. Many other fish such as guppies also exhibit sexual dimorphism. Extreme sexual size dimorphism, with females larger than males, is quite common in spiders and birds of prey.

The Role of Male-Male Competition in Sexual Selection

Male-male competition occurs when two males of the same species compete for the opportunity to mate with a female. Sexually dimorphic traits, size, sex ratio and the social situation

may all play a role in the effects male-male competition has on the

reproductive success of a male and the mate choice of a female.

Conditions that Influence Competition

Sex Ratio

Japanese medaka, Orzyas latipes.

There are multiple types of male-male competition that may occur in a

population at different times depending on the conditions. Competition

variation occurs based on the frequency of various mating behaviours

present in the population. One factor that can influence the type of competition observed is the population density of males.

When there is a high density of males present in the population,

competition tends to be less aggressive and therefore sneak tactics and

disruptions techniques are more often employed. These techniques often indicate a type of competition referred to as scramble competition. In Japanese medaka, Oryzias latipes,

sneaking behaviours refer to when a male interrupts a mating pair

during copulation by grasping on to either the male or the female and

releasing their own sperm in the hopes of being the one to fertilize the

female.

Disruption is a technique which involves one male bumping the male that

is copulating with the female away just before his sperm is released

and the eggs are fertilized.

However, all techniques are not equally successful when in

competition for reproductive success. Disruption results in a shorter

copulation period and can therefore disrupt the fertilization of the

eggs by the sperm, which frequently results in lower rates of

fertilization and smaller clutch size.

Resource Value and Social Ranking

Another

factor that can influence male-male competition is the value of the

resource to competitors. Male-male competition can pose many risks to a

male's fitness, such as high energy expenditure, physical injury, lower

sperm quality and lost paternity.

The risk of competition must therefore be worth the value of the

resource. A male is more likely to engage in competition for a resource

that improves their reproductive success if the resource value is

higher. While male-male competition can occur in the presence or absence

of a female, competition occurs more frequently in the presence of a

female.

The presence of a female directly increases the resource value of a

territory or shelter and so the males are more likely to accept the risk

of competition when a female is present. The smaller males of a species are also more likely to engage in competition with larger males in the presence of a female.

Due to the higher level of risk for subordinate males, they tend to

engage in competition less frequently than larger, more dominant males

and therefore breed less frequently than dominant males. This is seen in many species, such as the Omei treefrog, Rhacophorus omeimontis, where larger males obtained more mating opportunities and successfully mated with larger mates.

Winner-Loser Effects

A third factor that can impact the success of a male in competition is winner-loser effects. Burrowing crickets, velarifictorous aspersus, compete for burrows to attract females using their large mandibles for fighting. Female burrowing crickets, are more likely to choose winner of a competition in the 2 hours after the fight.

The presence winning male suppresses mating behaviours of the losing

males because the winning male tends to produce more frequent and

enhanced mating calls in this period of time.

Effect of Male-Male Competition on Female Fitness

Male-male

competition can both positively and negatively affect female fitness.

When there is a high density of males in a population and a large number

of males attempting to mate with the female, she is more likely to

resist mating attempts, resulting in lower fertilization rates. High levels of male-male competition can also result in a reduction in female investment in mating. Many forms of competition can also cause significant distress for the female negatively impacting her ability to reproduce.

An increase in male-male competition can affect a females ability to

select the best mates, and therefore decrease the likelihood of

successful reproduction.

However, group mating in Japanese medaka

has been shown to positively affect the fitness of females due to an

increase in genetic variation, a higher likelihood of paternal care and a

higher likelihood of successful fertilization.

Examples

A leaf-footed cactus bug, Narnia femorata.

In Japanese medaka, females mate daily during mating season. Males compete for the opportunity to mate with the female by displaying themselves aggressively and chasing each other.

To obtain the selection of the females, they court the females prior to

copulation by performing a courting behaviour referred to as "quick

circles".

In leaf-footed cactus bugs, Narnia femorata, males compete for territories where females can lay their eggs. Males compete more intensely for cacti territories with fruit to attract females. In this species, the males possess sexually dimorphic traits, such as

their larger size and hind legs, which are used to gain the most

advantage over competitors when females are present, but are not used in

the absence of females.

Anuran (such as frogs) select habitats (pools) free of conspecifics in order to minimize male-male competition for both themselves and their offspring.

Displays are used in attempt to keep competitors out of their territory

and deter sneaking behaviours, while fighting is only used when

necessary due to the high costs and risks associated with fighting.

In different taxa

SEM image of lateral view of a love dart of the land snail Monachoides vicinus. The scale bar is 500 μm (0.5 mm).

- Sexual selection in birds - mammals - humans -scaled reptiles - amphibians - insects - spiders - major histocompatibility complex

Human spermatozoa can reach 250 million in a single ejaculation

Sexual selection has been observed to occur in plants, animals and fungi. In certain hermaphroditic snail and slug species of molluscs the throwing of love darts is a form of sexual selection. Certain male insects of the lepidoptera order of insects cement the vaginal pores of their females.

Today, biologists say that certain evolutionary traits can be explained by intraspecific competition - competition between members of the same species - distinguishing between competition before or after sexual intercourse.

Illustration from The Descent of Man showing the tufted coquette Lophornis ornatus: female on left, ornamented male on right

Before copulation, intrasexual selection - usually between males - may take the form of male-to-male combat. Also, intersexual selection, or mate choice, occurs when females choose between male mates.

Traits selected by male combat are called secondary sexual

characteristics (including horns, antlers, etc.), which Darwin described

as "weapons", while traits selected by mate (usually female) choice are

called "ornaments". Due to their sometimes greatly exaggerated nature,

secondary sexual characteristics can prove to be a hindrance to an

animal, thereby lowering its chances of survival. For example, the large

antlers of a moose are bulky and heavy and slow the creature's flight

from predators; they also can become entangled in low-hanging tree

branches and shrubs, and undoubtedly have led to the demise of many

individuals. Bright colourations and showy ornamenations, such as those

seen in many male birds, in addition to capturing the eyes of females,

also attract the attention of predators. Some of these traits also

represent energetically costly investments for the animals that bear

them. Because traits held to be due to sexual selection often conflict

with the survival fitness of the individual, the question then arises as

to why, in nature, in which survival of the fittest

is considered the rule of thumb, such apparent liabilities are allowed

to persist. However, one must also consider that intersexual selection

can occur with an emphasis on resources that one sex possesses rather

than morphological and physiological differences. For example, males of Euglossa imperialis,

a non-social bee species, form aggregations of territories considered

to be leks, to defend fragrant-rich primary territories. The purpose of

these aggregations is only facultative, since the more suitable

fragrant-rich sites there are, the more habitable territories there are

to inhabit, giving females of this species a large selection of males

with whom to potentially mate.

After copulation, male–male competition distinct from conventional aggression may take the form of sperm competition, as described by Parker in 1970. More recently, interest has arisen in cryptic female choice, a phenomenon of internally fertilised animals such as mammals and birds, where a female can get rid of a male's sperm without his knowledge.

Victorian

cartoonists quickly picked up on Darwin's ideas about display in sexual

selection. Here he is fascinated by the apparent steatopygia in the latest fashion.

Finally, sexual conflict is said to occur between breeding partners, sometimes leading to an evolutionary arms race between males and females. Sexual selection can also occur as a product of pheromone release, such as with the stingless bee, Trigona corvina.

Female mating preferences are widely recognized as being

responsible for the rapid and divergent evolution of male secondary

sexual traits.

Females of many animal species prefer to mate with males with external

ornaments - exaggerated features of morphology such as elaborate sex

organs. These preferences may arise when an arbitrary female preference

for some aspect of male morphology — initially, perhaps, a result of genetic drift — creates, in due course, selection for males with the appropriate ornament. One interpretation of this is known as the sexy son hypothesis. Alternatively, genes that enable males to develop impressive ornaments or fighting ability may simply show off greater disease resistance or a more efficient metabolism, features that also benefit females. This idea is known as the good genes hypothesis.

Bright colors that develop in animals during mating season

function to attract partners. It has been suggested that there is a

causal link between strength of display of ornaments involved in sexual

selection and free radical biology. To test this idea, experiments were performed on male painted dragon lizards.

Male lizards are brightly conspicuous in their breeding coloration,

but their color declines with aging. Experiments involving

administration of antioxidants to these males led to the conclusion that breeding coloration is a reflection of innate anti-oxidation capacity that protects against oxidative damage, including oxidative DNA damage. Thus color could act as a “health certificate” that allows females to visualize the underlying oxidative stress induced damage in potential mates.

Darwin conjectured that heritable traits such as beards and hairlessness in different human populations are results of sexual selection in humans. Geoffrey Miller

has hypothesized that many human behaviours not clearly tied to

survival benefits, such as humour, music, visual art, verbal creativity,

and some forms of altruism,

are courtship adaptations that have been favoured through sexual

selection. In that view, many human artefacts could be considered

subject to sexual selection as part of the extended phenotype, for instance clothing that enhances sexually selected traits. Some argue that the evolution of human intelligence is a sexually selected trait, as it would not confer enough fitness in itself relative to its high maintenance costs.