Wood is a porous and fibrous structural tissue found in the stems and roots of trees and other woody plants. It is an organic material, a natural composite of cellulose fibers that are strong in tension and embedded in a matrix of lignin that resists compression. Wood is sometimes defined as only the secondary xylem in the stems of trees, or it is defined more broadly to include the same type of tissue elsewhere such as in the roots of trees or shrubs.

In a living tree it performs a support function, enabling woody plants

to grow large or to stand up by themselves. It also conveys water and nutrients between the leaves,

other growing tissues, and the roots. Wood may also refer to other

plant materials with comparable properties, and to material engineered

from wood, or wood chips or fiber.

Wood has been used for thousands of years for fuel, as a construction material, for making tools and weapons, furniture and paper. More recently it emerged as a feedstock for the production of purified cellulose and its derivatives, such as cellophane and cellulose acetate.

As of 2005, the growing stock of forests worldwide was about 434 billion cubic meters, 47% of which was commercial. As an abundant, carbon-neutral renewable resource, woody materials have been of intense interest as a source of renewable energy. In 1991 approximately 3.5 billion cubic meters of wood were harvested. Dominant uses were for furniture and building construction.

Wood can be dated by carbon dating and in some species by dendrochronology to determine when a wooden object was created.

People have used wood for thousands of years for many purposes, including as a fuel or as a construction material for making houses, tools, weapons, furniture, packaging, artworks, and paper. Known constructions using wood date back ten thousand years. Buildings like the European Neolithic long house were made primarily of wood.

Recent use of wood has been enhanced by the addition of steel and bronze into construction.

The year-to-year variation in tree-ring widths and isotopic abundances gives clues to the prevailing climate at the time a tree was cut.

As of 2005, the growing stock of forests worldwide was about 434 billion cubic meters, 47% of which was commercial. As an abundant, carbon-neutral renewable resource, woody materials have been of intense interest as a source of renewable energy. In 1991 approximately 3.5 billion cubic meters of wood were harvested. Dominant uses were for furniture and building construction.

History

A 2011 discovery in the Canadian province of New Brunswick yielded the earliest known plants to have grown wood, approximately 395 to 400 million years ago.Wood can be dated by carbon dating and in some species by dendrochronology to determine when a wooden object was created.

People have used wood for thousands of years for many purposes, including as a fuel or as a construction material for making houses, tools, weapons, furniture, packaging, artworks, and paper. Known constructions using wood date back ten thousand years. Buildings like the European Neolithic long house were made primarily of wood.

Recent use of wood has been enhanced by the addition of steel and bronze into construction.

The year-to-year variation in tree-ring widths and isotopic abundances gives clues to the prevailing climate at the time a tree was cut.

Physical properties

Diagram of secondary growth in a tree

showing idealized vertical and horizontal sections. A new layer of wood

is added in each growing season, thickening the stem, existing branches

and roots, to form a growth ring.

Growth rings

Wood, in the strict sense, is yielded by trees, which increase in diameter by the formation, between the existing wood and the inner bark, of new woody layers which envelop the entire stem, living branches, and roots. This process is known as secondary growth; it is the result of cell division in the vascular cambium,

a lateral meristem, and subsequent expansion of the new cells. These

cells then go on to form thickened secondary cell walls, composed mainly

of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin.

Where the differences between the four seasons are distinct, e.g. New Zealand, growth can occur in a discrete annual or seasonal pattern, leading to growth rings;

these can usually be most clearly seen on the end of a log, but are

also visible on the other surfaces. If the distinctiveness between

seasons is annual (as is the case in equatorial regions, e.g. Singapore),

these growth rings are referred to as annual rings. Where there is

little seasonal difference growth rings are likely to be indistinct or

absent. If the bark of the tree has been removed in a particular area,

the rings will likely be deformed as the plant overgrows the scar.

If there are differences within a growth ring, then the part of a

growth ring nearest the center of the tree, and formed early in the

growing season when growth is rapid, is usually composed of wider

elements. It is usually lighter in color than that near the outer

portion of the ring, and is known as earlywood or springwood. The outer

portion formed later in the season is then known as the latewood or

summerwood. However, there are major differences, depending on the kind of wood (see below).

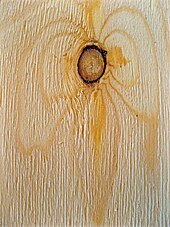

Knots

A knot on a tree trunk

As a tree grows, lower branches often die, and their bases may become

overgrown and enclosed by subsequent layers of trunk wood, forming a

type of imperfection known as a knot. The dead branch may not be

attached to the trunk wood except at its base, and can drop out after

the tree has been sawn into boards. Knots affect the technical

properties of the wood, usually reducing the local strength and

increasing the tendency for splitting along the wood grain,

but may be exploited for visual effect. In a longitudinally sawn plank,

a knot will appear as a roughly circular "solid" (usually darker) piece

of wood around which the grain

of the rest of the wood "flows" (parts and rejoins). Within a knot, the

direction of the wood (grain direction) is up to 90 degrees different

from the grain direction of the regular wood.

In the tree a knot is either the base of a side branch

or a dormant bud. A knot (when the base of a side branch) is conical in

shape (hence the roughly circular cross-section) with the inner tip at

the point in stem diameter at which the plant's vascular cambium was

located when the branch formed as a bud.

In grading lumber

and structural timber, knots are classified according to their form,

size, soundness, and the firmness with which they are held in place.

This firmness is affected by, among other factors, the length of time

for which the branch was dead while the attaching stem continued to

grow.

Wood knot in vertical section

Knots materially affect cracking and warping, ease in working, and cleavability of timber. They are defects which weaken timber and lower its value for structural purposes where strength is an important consideration. The weakening effect is much more serious when timber is subjected to forces perpendicular to the grain and/or tension than when under load along the grain and/or compression. The extent to which knots affect the strength of a beam depends upon their position, size, number, and condition. A knot on the upper side is compressed, while one on the lower side is subjected to tension. If there is a season check in the knot, as is often the case, it will offer little resistance to this tensile stress. Small knots, however, may be located along the neutral plane of a beam and increase the strength by preventing longitudinal shearing. Knots in a board or plank are least injurious when they extend through it at right angles to its broadest surface. Knots which occur near the ends of a beam do not weaken it. Sound knots which occur in the central portion one-fourth the height of the beam from either edge are not serious defects.

— Samuel J. Record, The Mechanical Properties of Wood

Knots do not necessarily influence the stiffness of structural

timber, this will depend on the size and location. Stiffness and elastic

strength are more dependent upon the sound wood than upon localized

defects. The breaking strength is very susceptible to defects. Sound

knots do not weaken wood when subject to compression parallel to the

grain.

In some decorative applications, wood with knots may be desirable to add visual interest. In applications where wood is painted,

such as skirting boards, fascia boards, door frames and furniture,

resins present in the timber may continue to 'bleed' through to the

surface of a knot for months or even years after manufacture and show as

a yellow or brownish stain. A knot primer paint or solution (knotting),

correctly applied during preparation, may do much to reduce this

problem but it is difficult to control completely, especially when using

mass-produced kiln-dried timber stocks.

Heartwood and sapwood

Heartwood (or duramen)

is wood that as a result of a naturally occurring chemical

transformation has become more resistant to decay. Heartwood formation

is a genetically programmed process that occurs spontaneously. Some

uncertainty exists as to whether the wood dies during heartwood

formation, as it can still chemically react to decay organisms, but only

once.

Heartwood is often visually distinct from the living sapwood, and

can be distinguished in a cross-section where the boundary will tend to

follow the growth rings. For example, it is sometimes much darker.

However, other processes such as decay or insect invasion can also

discolor wood, even in woody plants that do not form heartwood, which

may lead to confusion.

Sapwood (or alburnum) is the younger, outermost wood; in the growing tree it is living wood, and its principal functions are to conduct water from the roots to the leaves

and to store up and give back according to the season the reserves

prepared in the leaves. However, by the time they become competent to

conduct water, all xylem tracheids and vessels have lost their cytoplasm

and the cells are therefore functionally dead. All wood in a tree is

first formed as sapwood. The more leaves a tree bears and the more

vigorous its growth, the larger the volume of sapwood required. Hence

trees making rapid growth in the open have thicker sapwood for their

size than trees of the same species growing in dense forests. Sometimes

trees (of species that do form heartwood) grown in the open may become

of considerable size, 30 cm (12 in) or more in diameter, before any

heartwood begins to form, for example, in second-growth hickory, or open-grown pines.

The term heartwood derives solely from its position and

not from any vital importance to the tree. This is evidenced by the fact

that a tree can thrive with its heart completely decayed. Some species

begin to form heartwood very early in life, so having only a thin layer

of live sapwood, while in others the change comes slowly. Thin sapwood

is characteristic of such species as chestnut, black locust, mulberry, osage-orange, and sassafras, while in maple, ash, hickory, hackberry, beech, and pine, thick sapwood is the rule. Others never form heartwood.

No definite relation exists between the annual rings of growth

and the amount of sapwood. Within the same species the cross-sectional

area of the sapwood is very roughly proportional to the size of the

crown of the tree. If the rings are narrow, more of them are required

than where they are wide. As the tree gets larger, the sapwood must

necessarily become thinner or increase materially in volume. Sapwood is

relatively thicker in the upper portion of the trunk of a tree than near

the base, because the age and the diameter of the upper sections are

less.

When a tree is very young it is covered with limbs almost, if not

entirely, to the ground, but as it grows older some or all of them will

eventually die and are either broken off or fall off. Subsequent growth

of wood may completely conceal the stubs which will however remain as

knots. No matter how smooth and clear a log is on the outside, it is

more or less knotty near the middle. Consequently, the sapwood of an old

tree, and particularly of a forest-grown tree, will be freer from knots

than the inner heartwood. Since in most uses of wood, knots are defects

that weaken the timber and interfere with its ease of working and other

properties, it follows that a given piece of sapwood, because of its

position in the tree, may well be stronger than a piece of heartwood

from the same tree.

It is remarkable that the inner heartwood of old trees remains as

sound as it usually does, since in many cases it is hundreds, and in a

few instances thousands, of years old. Every broken limb or root, or

deep wound from fire, insects, or falling timber, may afford an entrance

for decay, which, once started, may penetrate to all parts of the

trunk. The larvae of many insects bore into the trees and their tunnels

remain indefinitely as sources of weakness. Whatever advantages,

however, that sapwood may have in this connection are due solely to its

relative age and position.

If a tree grows all its life in the open and the conditions of soil

and site remain unchanged, it will make its most rapid growth in youth,

and gradually decline. The annual rings of growth are for many years

quite wide, but later they become narrower and narrower. Since each

succeeding ring is laid down on the outside of the wood previously

formed, it follows that unless a tree materially increases its

production of wood from year to year, the rings must necessarily become

thinner as the trunk gets wider. As a tree reaches maturity its crown

becomes more open and the annual wood production is lessened, thereby

reducing still more the width of the growth rings. In the case of

forest-grown trees so much depends upon the competition of the trees in

their struggle for light and nourishment that periods of rapid and slow

growth may alternate. Some trees, such as southern oaks,

maintain the same width of ring for hundreds of years. Upon the whole,

however, as a tree gets larger in diameter the width of the growth rings

decreases.

Different pieces of wood cut from a large tree may differ

decidedly, particularly if the tree is big and mature. In some trees,

the wood laid on late in the life of a tree is softer, lighter, weaker,

and more even-textured than that produced earlier, but in other trees,

the reverse applies. This may or may not correspond to heartwood and

sapwood. In a large log the sapwood, because of the time in the life of

the tree when it was grown, may be inferior in hardness, strength, and toughness to equally sound heartwood from the same log. In a smaller tree, the reverse may be true.

Color

The wood of coast redwood is distinctively red.

In species which show a distinct difference between heartwood and

sapwood the natural color of heartwood is usually darker than that of

the sapwood, and very frequently the contrast is conspicuous (see

section of yew log above). This is produced by deposits in the heartwood

of chemical substances, so that a dramatic color variation does not

imply a significant difference in the mechanical properties of heartwood

and sapwood, although there may be a marked biochemical difference

between the two.

Some experiments on very resinous longleaf pine specimens indicate an increase in strength, due to the resin

which increases the strength when dry. Such resin-saturated heartwood

is called "fat lighter". Structures built of fat lighter are almost

impervious to rot and termites; however they are very flammable. Stumps

of old longleaf pines are often dug, split into small pieces and sold

as kindling for fires. Stumps thus dug may actually remain a century or

more since being cut. Spruce impregnated with crude resin and dried is also greatly increased in strength thereby.

Since the latewood of a growth ring is usually darker in color

than the earlywood, this fact may be used in visually judging the

density, and therefore the hardness and strength of the material. This

is particularly the case with coniferous woods. In ring-porous woods the

vessels of the early wood often appear on a finished surface as darker

than the denser latewood, though on cross sections of heartwood the

reverse is commonly true. Otherwise the color of wood is no indication

of strength.

Abnormal discoloration of wood often denotes a diseased condition, indicating unsoundness. The black check in western hemlock

is the result of insect attacks. The reddish-brown streaks so common in

hickory and certain other woods are mostly the result of injury by

birds. The discoloration is merely an indication of an injury, and in

all probability does not of itself affect the properties of the wood.

Certain rot-producing fungi impart to wood characteristic colors which thus become symptomatic of weakness; however an attractive effect known as spalting

produced by this process is often considered a desirable

characteristic. Ordinary sap-staining is due to fungal growth, but does

not necessarily produce a weakening effect.

Water content

Water occurs in living wood in three locations, namely:

- in the cell walls,

- in the protoplasmic contents of the cells

- as free water in the cell cavities and spaces, especially of the xylem

In heartwood it occurs only in the first and last forms. Wood that is

thoroughly air-dried retains 8–16% of the water in the cell walls, and

none, or practically none, in the other forms. Even oven-dried wood

retains a small percentage of moisture, but for all except chemical

purposes, may be considered absolutely dry.

The general effect of the water content upon the wood substance

is to render it softer and more pliable. A similar effect occurs in the

softening action of water on rawhide, paper, or cloth. Within certain

limits, the greater the water content, the greater its softening effect.

Drying produces a decided increase in the strength of wood,

particularly in small specimens. An extreme example is the case of a

completely dry spruce

block 5 cm in section, which will sustain a permanent load four times

as great as a green (undried) block of the same size will.

The greatest strength increase due to drying is in the ultimate crushing strength, and strength at elastic limit in endwise compression; these are followed by the modulus of rupture, and stress at elastic limit in cross-bending, while the modulus of elasticity is least affected.

Structure

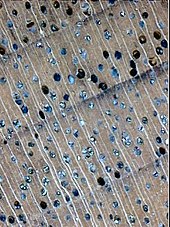

Magnified cross-section of black walnut,

showing the vessels, rays (white lines) and annual rings: this is

intermediate between diffuse-porous and ring-porous, with vessel size

declining gradually

Wood is a heterogeneous, hygroscopic, cellular and anisotropic material. It consists of cells, and the cell walls are composed of micro-fibrils of cellulose (40–50%) and hemicellulose (15–25%) impregnated with lignin (15–30%).

In coniferous or softwood species the wood cells are mostly of one kind, tracheids, and as a result the material is much more uniform in structure than that of most hardwoods. There are no vessels ("pores") in coniferous wood such as one sees so prominently in oak and ash, for example.

The structure of hardwoods is more complex. The water conducting capability is mostly taken care of by vessels: in some cases (oak, chestnut, ash) these are quite large and distinct, in others (buckeye, poplar, willow) too small to be seen without a hand lens. In discussing such woods it is customary to divide them into two large classes, ring-porous and diffuse-porous.

In ring-porous species, such as ash, black locust, catalpa, chestnut, elm, hickory, mulberry, and oak,

the larger vessels or pores (as cross sections of vessels are called)

are localized in the part of the growth ring formed in spring, thus

forming a region of more or less open and porous tissue. The rest of the

ring, produced in summer, is made up of smaller vessels and a much

greater proportion of wood fibers. These fibers are the elements which

give strength and toughness to wood, while the vessels are a source of

weakness.

In diffuse-porous woods the pores are evenly sized so that the

water conducting capability is scattered throughout the growth ring

instead of being collected in a band or row. Examples of this kind of

wood are alder, basswood, birch, buckeye, maple, willow, and the Populus species such as aspen, cottonwood and poplar. Some species, such as walnut and cherry, are on the border between the two classes, forming an intermediate group.

Earlywood and latewood

In softwood

Earlywood and latewood in a softwood; radial view, growth rings closely spaced in Rocky Mountain Douglas-fir

In temperate softwoods, there often is a marked difference between

latewood and earlywood. The latewood will be denser than that formed

early in the season. When examined under a microscope, the cells of

dense latewood are seen to be very thick-walled and with very small cell

cavities, while those formed first in the season have thin walls and

large cell cavities. The strength is in the walls, not the cavities.

Hence the greater the proportion of latewood, the greater the density

and strength. In choosing a piece of pine where strength or stiffness is

the important consideration, the principal thing to observe is the

comparative amounts of earlywood and latewood. The width of ring is not

nearly so important as the proportion and nature of the latewood in the

ring.

If a heavy piece of pine is compared with a lightweight piece it

will be seen at once that the heavier one contains a larger proportion

of latewood than the other, and is therefore showing more clearly

demarcated growth rings. In white pines

there is not much contrast between the different parts of the ring, and

as a result the wood is very uniform in texture and is easy to work. In

hard pines,

on the other hand, the latewood is very dense and is deep-colored,

presenting a very decided contrast to the soft, straw-colored earlywood.

It is not only the proportion of latewood, but also its quality,

that counts. In specimens that show a very large proportion of latewood

it may be noticeably more porous and weigh considerably less than the

latewood in pieces that contain less latewood. One can judge comparative

density, and therefore to some extent strength, by visual inspection.

No satisfactory explanation can as yet be given for the exact

mechanisms determining the formation of earlywood and latewood. Several

factors may be involved. In conifers, at least, rate of growth alone

does not determine the proportion of the two portions of the ring, for

in some cases the wood of slow growth is very hard and heavy, while in

others the opposite is true. The quality of the site where the tree

grows undoubtedly affects the character of the wood formed, though it is

not possible to formulate a rule governing it. In general, however, it

may be said that where strength or ease of working is essential, woods

of moderate to slow growth should be chosen.

In ring-porous woods

Earlywood and latewood in a ring-porous wood (ash) in a Fraxinus excelsior; tangential view, wide growth rings

In ring-porous woods, each season's growth is always well defined,

because the large pores formed early in the season abut on the denser

tissue of the year before.

In the case of the ring-porous hardwoods, there seems to exist a

pretty definite relation between the rate of growth of timber and its

properties. This may be briefly summed up in the general statement that

the more rapid the growth or the wider the rings of growth, the heavier,

harder, stronger, and stiffer the wood. This, it must be remembered,

applies only to ring-porous woods such as oak, ash, hickory, and others

of the same group, and is, of course, subject to some exceptions and

limitations.

In ring-porous woods of good growth, it is usually the latewood

in which the thick-walled, strength-giving fibers are most abundant. As

the breadth of ring diminishes, this latewood is reduced so that very

slow growth produces comparatively light, porous wood composed of

thin-walled vessels and wood parenchyma. In good oak, these large

vessels of the earlywood occupy from 6 to 10 percent of the volume of

the log, while in inferior material they may make up 25% or more. The

latewood of good oak is dark colored and firm, and consists mostly of

thick-walled fibers which form one-half or more of the wood. In inferior

oak, this latewood is much reduced both in quantity and quality. Such

variation is very largely the result of rate of growth.

Wide-ringed wood is often called "second-growth", because the

growth of the young timber in open stands after the old trees have been

removed is more rapid than in trees in a closed forest, and in the

manufacture of articles where strength is an important consideration

such "second-growth" hardwood material is preferred. This is

particularly the case in the choice of hickory for handles and spokes. Here not only strength, but toughness and resilience are important.

The results of a series of tests on hickory by the U.S. Forest Service show that:

- "The work or shock-resisting ability is greatest in wide-ringed wood that has from 5 to 14 rings per inch (rings 1.8-5 mm thick), is fairly constant from 14 to 38 rings per inch (rings 0.7–1.8 mm thick), and decreases rapidly from 38 to 47 rings per inch (rings 0.5–0.7 mm thick). The strength at maximum load is not so great with the most rapid-growing wood; it is maximum with from 14 to 20 rings per inch (rings 1.3–1.8 mm thick), and again becomes less as the wood becomes more closely ringed. The natural deduction is that wood of first-class mechanical value shows from 5 to 20 rings per inch (rings 1.3–5 mm thick) and that slower growth yields poorer stock. Thus the inspector or buyer of hickory should discriminate against timber that has more than 20 rings per inch (rings less than 1.3 mm thick). Exceptions exist, however, in the case of normal growth upon dry situations, in which the slow-growing material may be strong and tough."

The effect of rate of growth on the qualities of chestnut wood is summarized by the same authority as follows:

- "When the rings are wide, the transition from spring wood to summer wood is gradual, while in the narrow rings the spring wood passes into summer wood abruptly. The width of the spring wood changes but little with the width of the annual ring, so that the narrowing or broadening of the annual ring is always at the expense of the summer wood. The narrow vessels of the summer wood make it richer in wood substance than the spring wood composed of wide vessels. Therefore, rapid-growing specimens with wide rings have more wood substance than slow-growing trees with narrow rings. Since the more the wood substance the greater the weight, and the greater the weight the stronger the wood, chestnuts with wide rings must have stronger wood than chestnuts with narrow rings. This agrees with the accepted view that sprouts (which always have wide rings) yield better and stronger wood than seedling chestnuts, which grow more slowly in diameter."

In diffuse-porous woods

In the diffuse-porous woods, the demarcation between rings is not

always so clear and in some cases is almost (if not entirely) invisible

to the unaided eye. Conversely, when there is a clear demarcation there

may not be a noticeable difference in structure within the growth ring.

In diffuse-porous woods, as has been stated, the vessels or pores

are even-sized, so that the water conducting capability is scattered

throughout the ring instead of collected in the earlywood. The effect of

rate of growth is, therefore, not the same as in the ring-porous woods,

approaching more nearly the conditions in the conifers. In general it

may be stated that such woods of medium growth afford stronger material

than when very rapidly or very slowly grown. In many uses of wood, total

strength is not the main consideration. If ease of working is prized,

wood should be chosen with regard to its uniformity of texture and

straightness of grain, which will in most cases occur when there is

little contrast between the latewood of one season's growth and the

earlywood of the next.

Monocot wood

Structural material that resembles ordinary, "dicot" or conifer

timber in its gross handling characteristics is produced by a number of monocot plants, and these also are colloquially called wood. Of these, bamboo,

botanically a member of the grass family, has considerable economic

importance, larger culms being widely used as a building and

construction material and in the manufacture of engineered flooring,

panels and veneer. Another major plant group that produces material that often is called wood are the palms. Of much less importance are plants such as Pandanus, Dracaena and Cordyline. With all this material, the structure and composition of the processed raw material is quite different from ordinary wood.

Specific gravity

The single most revealing property of wood as an indicator of wood quality is specific gravity (Timell 1986),

as both pulp yield and lumber strength are determined by it. Specific

gravity is the ratio of the mass of a substance to the mass of an equal

volume of water; density is the ratio of a mass of a quantity of a

substance to the volume of that quantity and is expressed in mass per

unit substance, e.g., grams per milliliter (g/cm3 or g/ml).

The terms are essentially equivalent as long as the metric system is

used. Upon drying, wood shrinks and its density increases. Minimum

values are associated with green (water-saturated) wood and are referred

to as basic specific gravity (Timell 1986).

Wood density

Wood density is determined by multiple growth and physiological

factors compounded into “one fairly easily measured wood characteristic”

(Elliott 1970).

Age, diameter, height, radial (trunk) growth, geographical location, site and growing conditions, silvicultural

treatment, and seed source all to some degree influence wood density.

Variation is to be expected. Within an individual tree, the variation in

wood density is often as great as or even greater than that between

different trees (Timell 1986). Variation of specific gravity within the bole of a tree can occur in either the horizontal or vertical direction.

Hard and soft woods

It is common to classify wood as either softwood or hardwood. The wood from conifers (e.g. pine) is called softwood, and the wood from dicotyledons

(usually broad-leaved trees, (e.g. oak) is called hardwood. These names

are a bit misleading, as hardwoods are not necessarily hard, and

softwoods are not necessarily soft. The well-known balsa (a hardwood) is

actually softer than any commercial softwood. Conversely, some

softwoods (e.g. yew) are harder than many hardwoods.

There is a strong relationship between the properties of wood and

the properties of the particular tree that yielded it. The density of

wood varies with species. The density of a wood correlates with its

strength (mechanical properties). For example, mahogany is a medium-dense hardwood that is excellent for fine furniture crafting, whereas balsa is light, making it useful for model building. One of the densest woods is black ironwood.

Chemistry of wood

Chemical structure of lignin, which comprises about 25% of wood dry matter and is responsible for many of its properties.

The chemical composition of wood varies from species to species, but

is approximately 50% carbon, 42% oxygen, 6% hydrogen, 1% nitrogen, and

1% other elements (mainly calcium, potassium, sodium, magnesium, iron, and manganese) by weight. Wood also contains sulfur, chlorine, silicon, phosphorus, and other elements in small quantity.

Aside from water, wood has three main components. Cellulose, a crystalline polymer derived from glucose, constitutes about 41–43%. Next in abundance is hemicellulose, which is around 20% in deciduous trees but near 30% in conifers. It is mainly five-carbon sugars that are linked in an irregular manner, in contrast to the cellulose. Lignin

is the third component at around 27% in coniferous wood vs. 23% in

deciduous trees. Lignin confers the hydrophobic properties reflecting

the fact that it is based on aromatic rings.

These three components are interwoven, and direct covalent linkages

exist between the lignin and the hemicellulose. A major focus of the

paper industry is the separation of the lignin from the cellulose, from

which paper is made.

In chemical terms, the difference between hardwood and softwood is reflected in the composition of the constituent lignin. Hardwood lignin is primarily derived from sinapyl alcohol and coniferyl alcohol. Softwood lignin is mainly derived from coniferyl alcohol.

Extractives

Aside from the lignocellulose, wood consists of a variety of low molecular weight organic compounds, called extractives. The wood extractives are fatty acids, resin acids, waxes and terpenes. For example, rosin is exuded by conifers as protection from insects. The extraction of these organic materials from wood provides tall oil, turpentine, and rosin.

Uses

Fuel

Wood has a long history of being used as fuel,

which continues to this day, mostly in rural areas of the world.

Hardwood is preferred over softwood because it creates less smoke and

burns longer. Adding a woodstove or fireplace to a home is often felt to

add ambiance and warmth.

Construction

The Saitta House, Dyker Heights, Brooklyn, New York built in 1899 is made of and decorated in wood.

Wood has been an important construction material since humans began

building shelters, houses and boats. Nearly all boats were made out of

wood until the late 19th century, and wood remains in common use today

in boat construction. Elm

in particular was used for this purpose as it resisted decay as long as

it was kept wet (it also served for water pipe before the advent of

more modern plumbing).

Wood to be used for construction work is commonly known as lumber in North America. Elsewhere, lumber usually refers to felled trees, and the word for sawn planks ready for use is timber. In Medieval Europe oak

was the wood of choice for all wood construction, including beams,

walls, doors, and floors. Today a wider variety of woods is used: solid

wood doors are often made from poplar, small-knotted pine, and Douglas fir.

The churches of Kizhi, Russia are among a handful of World Heritage Sites built entirely of wood, without metal joints.

New domestic housing in many parts of the world today is commonly made from timber-framed construction. Engineered wood

products are becoming a bigger part of the construction industry. They

may be used in both residential and commercial buildings as structural

and aesthetic materials.

In buildings made of other materials, wood will still be found as

a supporting material, especially in roof construction, in interior

doors and their frames, and as exterior cladding.

Wood is also commonly used as shuttering material to form the mold into which concrete is poured during reinforced concrete construction.

Wood flooring

Wood can be cut into straight planks and made into a wood flooring.

A

solid wood floor is a floor laid with planks or battens created from a

single piece of timber, usually a hardwood. Since wood is hydroscopic

(it acquires and loses moisture from the ambient conditions around it)

this potential instability effectively limits the length and width of

the boards.

Solid hardwood flooring is usually cheaper than engineered

timbers and damaged areas can be sanded down and refinished repeatedly,

the number of times being limited only by the thickness of wood above

the tongue.

Solid hardwood floors were originally used for structural

purposes, being installed perpendicular to the wooden support beams of a

building (the joists or bearers) and solid construction timber is still

often used for sports floors as well as most traditional wood blocks, mosaics and parquetry.

Engineered wood

Engineered wood products, glued building products "engineered" for

application-specific performance requirements, are often used in

construction and industrial applications. Glued engineered wood products

are manufactured by bonding together wood strands, veneers, lumber or

other forms of wood fiber with glue to form a larger, more efficient

composite structural unit.

These products include glued laminated timber (glulam), wood structural panels (including plywood, oriented strand board and composite panels), laminated veneer lumber (LVL) and other structural composite lumber (SCL) products, parallel strand lumber, and I-joists. Approximately 100 million cubic meters of wood was consumed for this purpose in 1991. The trends suggest that particle board and fiber board will overtake plywood.

Wood unsuitable for construction in its native form may be broken

down mechanically (into fibers or chips) or chemically (into cellulose)

and used as a raw material for other building materials, such as

engineered wood, as well as chipboard, hardboard, and medium-density fiberboard

(MDF). Such wood derivatives are widely used: wood fibers are an

important component of most paper, and cellulose is used as a component

of some synthetic materials. Wood derivatives can be used for kinds of flooring, for example laminate flooring.

Furniture and utensils

Wood has always been used extensively for furniture, such as chairs and beds. It is also used for tool handles and cutlery, such as chopsticks, toothpicks, and other utensils, like the wooden spoon and pencil.

Next generation wood products

Further developments include new lignin

glue applications, recyclable food packaging, rubber tire replacement

applications, anti-bacterial medical agents, and high strength fabrics

or composites.

As scientists and engineers further learn and develop new techniques to

extract various components from wood, or alternatively to modify wood,

for example by adding components to wood, new more advanced products

will appear on the marketplace. Moisture content electronic monitoring

can also enhance next generation wood protection.

In the arts

Wood has long been used as an artistic medium. It has been used to make sculptures and carvings for millennia. Examples include the totem poles carved by North American indigenous people from conifer trunks, often Western Red Cedar (Thuja plicata).

Other uses of wood in the arts include:

- Woodcut printmaking and engraving

- Wood can be a surface to paint on, such as in panel painting

- Many musical instruments are made mostly or entirely of wood

Sports and recreational equipment

Many types of sports equipment are made of wood, or were constructed of wood in the past. For example, cricket bats are typically made of white willow. The baseball bats which are legal for use in Major League Baseball are frequently made of ash wood or hickory, and in recent years have been constructed from maple even though that wood is somewhat more fragile. NBA courts have been traditionally made out of parquetry.

Many other types of sports and recreation equipment, such as skis, ice hockey sticks, lacrosse sticks and archery bows, were commonly made of wood in the past, but have since been replaced with more modern materials such as aluminium, titanium or composite materials such as fiberglass and carbon fiber. One noteworthy example of this trend is the family of golf clubs commonly known as the woods, the heads of which were traditionally made of persimmon wood in the early days of the game of golf, but are now generally made of metal or (especially in the case of drivers) carbon-fiber composites.

Bacterial degradation

Little is known about the bacteria that degrade cellulose. Symbiotic bacteria in Xylophaga may play a role in the degradation of sunken wood; while bacteria such as Alphaproteobacteria, Flavobacteria, Actinobacteria, Clostridia, and Bacteroidetes have been detected in wood submerged over a year.