| Helium atom | |

|---|---|

|

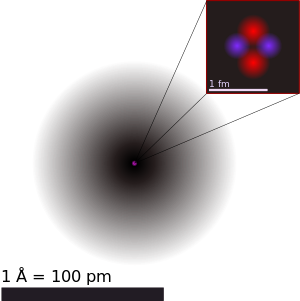

An illustration of the helium atom, depicting the nucleus (pink) and the electron cloud

distribution (black). The nucleus (upper right) in helium-4 is in

reality spherically symmetric and closely resembles the electron cloud,

although for more complicated nuclei this is not always the case. The

black bar is one angstrom (10−10 m or 100 pm).

| |

| Classification | |

| Smallest recognized division of a chemical element | |

| Properties | |

| Mass range | 1.67×10−27 to 4.52×10−25 kg |

| Electric charge | zero (neutral), or ion charge |

| Diameter range | 62 pm (He) to 520 pm (Cs) (data page) |

| Components | Electrons and a compact nucleus of protons and neutrons |

An atom is the smallest constituent unit of ordinary matter that constitutes a chemical element. Every solid, liquid, gas, and plasma is composed of neutral or ionized atoms. Atoms are extremely small; typical sizes are around 100 picometers (1×10−10 m, a ten-millionth of a millimeter, or 1/254,000,000 of an inch). They are so small that accurately predicting their behavior using classical physics – as if they were billiard balls, for example – is not possible. This is due to quantum effects. Current atomic models now use quantum principles to better explain and predict this behavior.

Every atom is composed of a nucleus and one or more electrons bound to the nucleus. The nucleus is made of one or more protons and a number of neutrons. Only the most common variety of hydrogen has no neutrons. Protons and neutrons are called nucleons. More than 99.94% of an atom's mass is in the nucleus. The protons have a positive electric charge whereas the electrons have a negative electric charge. The neutrons have no electric charge. If the number of protons and electrons are equal, then the atom is electrically neutral. If an atom has more or fewer electrons than protons, then it has an overall negative or positive charge, respectively. These atoms are called ions.

The electrons of an atom are attracted to the protons in an atomic nucleus by the electromagnetic force. The protons and neutrons in the nucleus are attracted to each other by the nuclear force. This force is usually stronger than the electromagnetic force that repels the positively charged protons from one another. Under certain circumstances, the repelling electromagnetic force becomes stronger than the nuclear force. In this case, the nucleus shatters and leaves behind different elements. This is a kind of nuclear decay. All electrons, nucleons, and nuclei alike are subatomic particles. The behavior of electrons in atoms is closer to a wave than a particle.

The number of protons in the nucleus, called the atomic number, defines to which chemical element the atom belongs. For example, each copper atom contains 29 protons. The number of neutrons defines the isotope of the element. Atoms can attach to one or more other atoms by chemical bonds to form chemical compounds such as molecules or crystals. The ability of atoms to associate and dissociate is responsible for most of the physical changes observed in nature. Chemistry is the discipline that studies these changes.

History of atomic theory

Atoms in philosophy

The idea that matter is made up of discrete units is a very old idea, appearing in many ancient cultures such as Greece and India. The word atomos, meaning "uncuttable", was coined by the ancient Greek philosophers Leucippus and his pupil Democritus (c. 460 – c. 370 BC). Democritus taught that atoms were infinite in number, uncreated, and eternal, and that the qualities of an object result from the kind of atoms that compose it. Democritus's atomism was refined and elaborated by the later philosopher Epicurus (341–270 BC). During the Early Middle Ages, atomism was mostly forgotten in western Europe, but survived among some groups of Islamic philosophers. During the twelfth century, atomism became known again in western Europe through references to it in the newly-rediscovered writings of Aristotle.In the fourteenth century, the rediscovery of major works describing atomist teachings, including Lucretius's De rerum natura and Diogenes Laërtius's Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, led to increased scholarly attention on the subject. Nonetheless, because atomism was associated with the philosophy of Epicureanism, which contradicted orthodox Christian teachings, belief in atoms was not considered acceptable. The French Catholic priest Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655) revived Epicurean atomism with modifications, arguing that atoms were created by God and, though extremely numerous, are not infinite. Gassendi's modified theory of atoms was popularized in France by the physician François Bernier (1620–1688) and in England by the natural philosopher Walter Charleton (1619–1707). The chemist Robert Boyle (1627–1691) and the physicist Isaac Newton (1642–1727) both defended atomism and, by the end of the seventeenth century, it had become accepted by portions of the scientific community.

First evidence-based theory

Various atoms and molecules as depicted in John Dalton's A New System of Chemical Philosophy (1808).

In the early 1800s, John Dalton used the concept of atoms to explain why elements always react in ratios of small whole numbers (the law of multiple proportions). For instance, there are two types of tin oxide: one is 88.1% tin and 11.9% oxygen and the other is 78.7% tin and 21.3% oxygen (tin(II) oxide and tin dioxide

respectively). This means that 100g of tin will combine either with

13.5g or 27g of oxygen. 13.5 and 27 form a ratio of 1:2, a ratio of

small whole numbers. This common pattern in chemistry suggested to

Dalton that elements react in multiples of discrete units — in other

words, atoms. In the case of tin oxides, one tin atom will combine with

either one or two oxygen atoms.

Dalton also believed atomic theory could explain why water

absorbs different gases in different proportions. For example, he found

that water absorbs carbon dioxide far better than it absorbs nitrogen.

Dalton hypothesized this was due to the differences between the masses

and configurations of the gases' respective particles, and carbon

dioxide molecules (CO2) are heavier and larger than nitrogen molecules (N2).

Brownian motion

In 1827, botanist Robert Brown

used a microscope to look at dust grains floating in water and

discovered that they moved about erratically, a phenomenon that became

known as "Brownian motion". This was thought to be caused by water molecules knocking the grains about. In 1905, Albert Einstein proved the reality of these molecules and their motions by producing the first statistical physics analysis of Brownian motion. French physicist Jean Perrin used Einstein's work to experimentally determine the mass and dimensions of atoms, thereby conclusively verifying Dalton's atomic theory.

Discovery of the electron

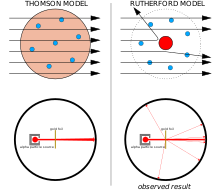

The Geiger–Marsden experiment Left: Expected results: alpha particles passing through the plum pudding model of the atom with negligible deflection. Right: Observed results: a small portion of the particles were deflected by the concentrated positive charge of the nucleus.

The physicist J.J. Thomson measured the mass of cathode rays, showing they were made of particles, but were around 1800 times lighter than the lightest atom, hydrogen. Therefore, they were not atoms, but a new particle, the first subatomic particle to be discovered, which he originally called "corpuscle" but was later named electron, after particles postulated by George Johnstone Stoney in 1874. He also showed they were identical to particles given off by photoelectric and radioactive materials. It was quickly recognized that they are the particles that carry electric currents in metal wires, and carry the negative electric charge within atoms. Thomson was given the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physics for this work. Thus he overturned the belief that atoms are the indivisible, ultimate particles of matter.

Thomson also incorrectly postulated that the low mass, negatively

charged electrons were distributed throughout the atom in a uniform sea

of positive charge. This became known as the plum pudding model.

Discovery of the nucleus

In 1909, Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, under the direction of Ernest Rutherford, bombarded a metal foil with alpha particles

to observe how they scattered. They expected all the alpha particles to

pass straight through with little deflection, because Thomson's model

said that the charges in the atom are so diffuse that their electric

fields could not affect the alpha particles much. However, Geiger and

Marsden spotted alpha particles being deflected by angles greater than

90°, which was supposed to be impossible according to Thomson's model.

To explain this, Rutherford proposed that the positive charge of the

atom is concentrated in a tiny nucleus at the center of the atom.

Discovery of isotopes

While experimenting with the products of radioactive decay, in 1913 radiochemist Frederick Soddy discovered that there appeared to be more than one type of atom at each position on the periodic table. The term isotope was coined by Margaret Todd as a suitable name for different atoms that belong to the same element. J.J. Thomson created a technique for isotope separation through his work on ionized gases, which subsequently led to the discovery of stable isotopes.

Bohr model

The

Bohr model of the atom, with an electron making instantaneous "quantum

leaps" from one orbit to another. This model is obsolete.

In 1913 the physicist Niels Bohr

proposed a model in which the electrons of an atom were assumed to

orbit the nucleus but could only do so in a finite set of orbits, and

could jump between these orbits only in discrete changes of energy

corresponding to absorption or radiation of a photon.

This quantization was used to explain why the electrons orbits are

stable (given that normally, charges in acceleration, including circular

motion, lose kinetic energy which is emitted as electromagnetic

radiation, see synchrotron radiation) and why elements absorb and emit electromagnetic radiation in discrete spectra.

Later in the same year Henry Moseley provided additional experimental evidence in favor of Niels Bohr's theory. These results refined Ernest Rutherford's and Antonius Van den Broek's model, which proposed that the atom contains in its nucleus a number of positive nuclear charges that is equal to its (atomic) number in the periodic table. Until these experiments, atomic number

was not known to be a physical and experimental quantity. That it is

equal to the atomic nuclear charge remains the accepted atomic model

today.

Chemical bonding explained

Chemical bonds between atoms were now explained, by Gilbert Newton Lewis in 1916, as the interactions between their constituent electrons. As the chemical properties of the elements were known to largely repeat themselves according to the periodic law, in 1919 the American chemist Irving Langmuir

suggested that this could be explained if the electrons in an atom were

connected or clustered in some manner. Groups of electrons were thought

to occupy a set of electron shells about the nucleus.

Further developments in quantum physics

The Stern–Gerlach experiment

of 1922 provided further evidence of the quantum nature of atomic

properties. When a beam of silver atoms was passed through a specially

shaped magnetic field, the beam was split in a way correlated with the

direction of an atom's angular momentum, or spin.

As this spin direction is initially random, the beam would be expected

to deflect in a random direction. Instead, the beam was split into two

directional components, corresponding to the atomic spin being oriented up or down with respect to the magnetic field.

In 1925 Werner Heisenberg published the first consistent mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics (Matrix Mechanics). One year earlier, in 1924, Louis de Broglie had proposed that all particles behave to an extent like waves and, in 1926, Erwin Schrödinger used this idea to develop a mathematical model of the atom (Wave Mechanics) that described the electrons as three-dimensional waveforms rather than point particles.

A consequence of using waveforms to describe particles is that it

is mathematically impossible to obtain precise values for both the position and momentum of a particle at a given point in time; this became known as the uncertainty principle, formulated by Werner Heisenberg in 1927.

In this concept, for a given accuracy in measuring a position one could

only obtain a range of probable values for momentum, and vice versa.

This model was able to explain observations of atomic behavior that previous models could not, such as certain structural and spectral patterns of atoms larger than hydrogen. Thus, the planetary model of the atom was discarded in favor of one that described atomic orbital zones around the nucleus where a given electron is most likely to be observed.

Discovery of the neutron

The development of the mass spectrometer

allowed the mass of atoms to be measured with increased accuracy. The

device uses a magnet to bend the trajectory of a beam of ions, and the

amount of deflection is determined by the ratio of an atom's mass to its

charge. The chemist Francis William Aston used this instrument to show that isotopes had different masses. The atomic mass of these isotopes varied by integer amounts, called the whole number rule. The explanation for these different isotopes awaited the discovery of the neutron, an uncharged particle with a mass similar to the proton, by the physicist James Chadwick

in 1932. Isotopes were then explained as elements with the same number

of protons, but different numbers of neutrons within the nucleus.

Fission, high-energy physics and condensed matter

In 1938, the German chemist Otto Hahn, a student of Rutherford, directed neutrons onto uranium atoms expecting to get transuranium elements. Instead, his chemical experiments showed barium as a product. A year later, Lise Meitner and her nephew Otto Frisch verified that Hahn's result were the first experimental nuclear fission. In 1944, Hahn received the Nobel prize in chemistry. Despite Hahn's efforts, the contributions of Meitner and Frisch were not recognized.

In the 1950s, the development of improved particle accelerators and particle detectors allowed scientists to study the impacts of atoms moving at high energies. Neutrons and protons were found to be hadrons, or composites of smaller particles called quarks. The standard model of particle physics

was developed that so far has successfully explained the properties of

the nucleus in terms of these sub-atomic particles and the forces that

govern their interactions.

Structure

Subatomic particles

Though the word atom originally denoted a particle that cannot

be cut into smaller particles, in modern scientific usage the atom is

composed of various subatomic particles. The constituent particles of an atom are the electron, the proton and the neutron; all three are fermions. However, the hydrogen-1 atom has no neutrons and the hydron ion has no electrons.

The electron is by far the least massive of these particles at 9.11×10−31 kg, with a negative electrical charge and a size that is too small to be measured using available techniques. It was the lightest particle with a positive rest mass measured, until the discovery of neutrino

mass. Under ordinary conditions, electrons are bound to the positively

charged nucleus by the attraction created from opposite electric

charges. If an atom has more or fewer electrons than its atomic number,

then it becomes respectively negatively or positively charged as a

whole; a charged atom is called an ion. Electrons have been known since the late 19th century, mostly thanks to J.J. Thomson.

Protons have a positive charge and a mass 1,836 times that of the electron, at 1.6726×10−27 kg. The number of protons in an atom is called its atomic number. Ernest Rutherford

(1919) observed that nitrogen under alpha-particle bombardment ejects

what appeared to be hydrogen nuclei. By 1920 he had accepted that the

hydrogen nucleus is a distinct particle within the atom and named it proton.

Neutrons have no electrical charge and have a free mass of 1,839 times the mass of the electron, or 1.6749×10−27 kg. Neutrons are the heaviest of the three constituent particles, but their mass can be reduced by the nuclear binding energy. Neutrons and protons (collectively known as nucleons) have comparable dimensions—on the order of 2.5×10−15 m—although the 'surface' of these particles is not sharply defined. The neutron was discovered in 1932 by the English physicist James Chadwick.

In the Standard Model

of physics, electrons are truly elementary particles with no internal

structure. However, both protons and neutrons are composite particles

composed of elementary particles called quarks. There are two types of quarks in atoms, each having a fractional electric charge. Protons are composed of two up quarks (each with charge +2/3) and one down quark (with a charge of −1/3).

Neutrons consist of one up quark and two down quarks. This distinction

accounts for the difference in mass and charge between the two

particles.

The quarks are held together by the strong interaction (or strong force), which is mediated by gluons. The protons and neutrons, in turn, are held to each other in the nucleus by the nuclear force,

which is a residuum of the strong force that has somewhat different

range-properties (see the article on the nuclear force for more). The

gluon is a member of the family of gauge bosons, which are elementary particles that mediate physical forces.

Nucleus

The binding energy needed for a nucleon to escape the nucleus, for various isotopes

All the bound protons and neutrons in an atom make up a tiny atomic nucleus, and are collectively called nucleons. The radius of a nucleus is approximately equal to 1.07 3√A fm, where A is the total number of nucleons. This is much smaller than the radius of the atom, which is on the order of 105 fm. The nucleons are bound together by a short-ranged attractive potential called the residual strong force. At distances smaller than 2.5 fm this force is much more powerful than the electrostatic force that causes positively charged protons to repel each other.

Atoms of the same element have the same number of protons, called the atomic number. Within a single element, the number of neutrons may vary, determining the isotope of that element. The total number of protons and neutrons determine the nuclide. The number of neutrons relative to the protons determines the stability of the nucleus, with certain isotopes undergoing radioactive decay.

The proton, the electron, and the neutron are classified as fermions. Fermions obey the Pauli exclusion principle which prohibits identical

fermions, such as multiple protons, from occupying the same quantum

state at the same time. Thus, every proton in the nucleus must occupy a

quantum state different from all other protons, and the same applies to

all neutrons of the nucleus and to all electrons of the electron cloud.

A nucleus that has a different number of protons than neutrons

can potentially drop to a lower energy state through a radioactive decay

that causes the number of protons and neutrons to more closely match.

As a result, atoms with matching numbers of protons and neutrons are

more stable against decay. However, with increasing atomic number, the

mutual repulsion of the protons requires an increasing proportion of

neutrons to maintain the stability of the nucleus, which slightly

modifies this trend of equal numbers of protons to neutrons.

Illustration

of a nuclear fusion process that forms a deuterium nucleus, consisting

of a proton and a neutron, from two protons. A positron (e+)—an antimatter electron—is emitted along with an electron neutrino.

The number of protons and neutrons in the atomic nucleus can be

modified, although this can require very high energies because of the

strong force. Nuclear fusion

occurs when multiple atomic particles join to form a heavier nucleus,

such as through the energetic collision of two nuclei. For example, at

the core of the Sun protons require energies of 3–10 keV to overcome

their mutual repulsion—the coulomb barrier—and fuse together into a single nucleus. Nuclear fission

is the opposite process, causing a nucleus to split into two smaller

nuclei—usually through radioactive decay. The nucleus can also be

modified through bombardment by high energy subatomic particles or

photons. If this modifies the number of protons in a nucleus, the atom

changes to a different chemical element.

If the mass of the nucleus following a fusion reaction is less

than the sum of the masses of the separate particles, then the

difference between these two values can be emitted as a type of usable

energy (such as a gamma ray, or the kinetic energy of a beta particle), as described by Albert Einstein's mass–energy equivalence formula, , where is the mass loss and is the speed of light. This deficit is part of the binding energy

of the new nucleus, and it is the non-recoverable loss of the energy

that causes the fused particles to remain together in a state that

requires this energy to separate.

The fusion of two nuclei that create larger nuclei with lower atomic numbers than iron and nickel—a total nucleon number of about 60—is usually an exothermic process that releases more energy than is required to bring them together. It is this energy-releasing process that makes nuclear fusion in stars a self-sustaining reaction. For heavier nuclei, the binding energy per nucleon

in the nucleus begins to decrease. That means fusion processes

producing nuclei that have atomic numbers higher than about 26, and atomic masses higher than about 60, is an endothermic process. These more massive nuclei can not undergo an energy-producing fusion reaction that can sustain the hydrostatic equilibrium of a star.

Electron cloud

A potential well, showing, according to classical mechanics, the minimum energy V(x) needed to reach each position x. Classically, a particle with energy E is constrained to a range of positions between x1 and x2.

The electrons in an atom are attracted to the protons in the nucleus by the electromagnetic force. This force binds the electrons inside an electrostatic potential well

surrounding the smaller nucleus, which means that an external source of

energy is needed for the electron to escape. The closer an electron is

to the nucleus, the greater the attractive force. Hence electrons bound

near the center of the potential well require more energy to escape than

those at greater separations.

Electrons, like other particles, have properties of both a particle and a wave. The electron cloud is a region inside the potential well where each electron forms a type of three-dimensional standing wave—a wave form that does not move relative to the nucleus. This behavior is defined by an atomic orbital,

a mathematical function that characterises the probability that an

electron appears to be at a particular location when its position is

measured. Only a discrete (or quantized) set of these orbitals exist around the nucleus, as other possible wave patterns rapidly decay into a more stable form. Orbitals can have one or more ring or node structures, and differ from each other in size, shape and orientation.

Wave functions of the first five atomic orbitals. The three 2p orbitals each display a single angular node that has an orientation and a minimum at the center.

Each atomic orbital corresponds to a particular energy level of the electron. The electron can change its state to a higher energy level by absorbing a photon with sufficient energy to boost it into the new quantum state. Likewise, through spontaneous emission,

an electron in a higher energy state can drop to a lower energy state

while radiating the excess energy as a photon. These characteristic

energy values, defined by the differences in the energies of the quantum

states, are responsible for atomic spectral lines.

The amount of energy needed to remove or add an electron—the electron binding energy—is far less than the binding energy of nucleons. For example, it requires only 13.6 eV to strip a ground-state electron from a hydrogen atom, compared to 2.23 million eV for splitting a deuterium nucleus. Atoms are electrically

neutral if they have an equal number of protons and electrons. Atoms

that have either a deficit or a surplus of electrons are called ions.

Electrons that are farthest from the nucleus may be transferred to

other nearby atoms or shared between atoms. By this mechanism, atoms are

able to bond into molecules and other types of chemical compounds like ionic and covalent network crystals.

Properties

Nuclear properties

By definition, any two atoms with an identical number of protons in their nuclei belong to the same chemical element. Atoms with equal numbers of protons but a different number of neutrons

are different isotopes of the same element. For example, all hydrogen

atoms admit exactly one proton, but isotopes exist with no neutrons (hydrogen-1, by far the most common form, also called protium), one neutron (deuterium), two neutrons (tritium) and more than two neutrons. The known elements form a set of atomic numbers, from the single proton element hydrogen up to the 118-proton element oganesson. All known isotopes of elements with atomic numbers greater than 82 are radioactive, although the radioactivity of element 83 (bismuth) is so slight as to be practically negligible.

About 339 nuclides occur naturally on Earth, of which 254 (about 75%) have not been observed to decay, and are referred to as "stable isotopes". However, only 90 of these nuclides are stable to all decay, even in theory.

Another 164 (bringing the total to 254) have not been observed to

decay, even though in theory it is energetically possible. These are

also formally classified as "stable". An additional 34 radioactive

nuclides have half-lives longer than 80 million years, and are

long-lived enough to be present from the birth of the solar system. This collection of 288 nuclides are known as primordial nuclides.

Finally, an additional 51 short-lived nuclides are known to occur

naturally, as daughter products of primordial nuclide decay (such as radium from uranium), or else as products of natural energetic processes on Earth, such as cosmic ray bombardment (for example, carbon-14).

For 80 of the chemical elements, at least one stable isotope

exists. As a rule, there is only a handful of stable isotopes for each

of these elements, the average being 3.2 stable isotopes per element.

Twenty-six elements have only a single stable isotope, while the largest

number of stable isotopes observed for any element is ten, for the

element tin. Elements 43, 61, and all elements numbered 83 or higher have no stable isotopes.

Stability of isotopes is affected by the ratio of protons to

neutrons, and also by the presence of certain "magic numbers" of

neutrons or protons that represent closed and filled quantum shells.

These quantum shells correspond to a set of energy levels within the shell model

of the nucleus; filled shells, such as the filled shell of 50 protons

for tin, confers unusual stability on the nuclide. Of the 254 known

stable nuclides, only four have both an odd number of protons and odd number of neutrons: hydrogen-2 (deuterium), lithium-6, boron-10 and nitrogen-14. Also, only four naturally occurring, radioactive odd–odd nuclides have a half-life over a billion years: potassium-40, vanadium-50, lanthanum-138 and tantalum-180m. Most odd–odd nuclei are highly unstable with respect to beta decay, because the decay products are even–even, and are therefore more strongly bound, due to nuclear pairing effects.

Mass

The large majority of an atom's mass comes from the protons and

neutrons that make it up. The total number of these particles (called

"nucleons") in a given atom is called the mass number.

It is a positive integer and dimensionless (instead of having dimension

of mass), because it expresses a count. An example of use of a mass

number is "carbon-12," which has 12 nucleons (six protons and six

neutrons).

The actual mass of an atom at rest is often expressed using the unified atomic mass unit (u), also called dalton (Da). This unit is defined as a twelfth of the mass of a free neutral atom of carbon-12, which is approximately 1.66×10−27 kg. Hydrogen-1 (the lightest isotope of hydrogen which is also the nuclide with the lowest mass) has an atomic weight of 1.007825 u. The value of this number is called the atomic mass.

A given atom has an atomic mass approximately equal (within 1%) to its

mass number times the atomic mass unit (for example the mass of a

nitrogen-14 is roughly 14 u). However, this number will not be exactly

an integer except in the case of carbon-12 (see below). The heaviest stable atom is lead-208, with a mass of 207.9766521 u.

As even the most massive atoms are far too light to work with directly, chemists instead use the unit of moles. One mole of atoms of any element always has the same number of atoms (about 6.022×1023).

This number was chosen so that if an element has an atomic mass of 1 u,

a mole of atoms of that element has a mass close to one gram. Because

of the definition of the unified atomic mass unit, each carbon-12 atom has an atomic mass of exactly 12 u, and so a mole of carbon-12 atoms weighs exactly 0.012 kg.

Shape and size

Atoms lack a well-defined outer boundary, so their dimensions are usually described in terms of an atomic radius. This is a measure of the distance out to which the electron cloud extends from the nucleus.

However, this assumes the atom to exhibit a spherical shape, which is

only obeyed for atoms in vacuum or free space. Atomic radii may be

derived from the distances between two nuclei when the two atoms are

joined in a chemical bond.

The radius varies with the location of an atom on the atomic chart, the

type of chemical bond, the number of neighboring atoms (coordination number) and a quantum mechanical property known as spin. On the periodic table of the elements, atom size tends to increase when moving down columns, but decrease when moving across rows (left to right). Consequently, the smallest atom is helium with a radius of 32 pm, while one of the largest is caesium at 225 pm.

When subjected to external forces, like electrical fields, the shape of an atom may deviate from spherical symmetry. The deformation depends on the field magnitude and the orbital type of outer shell electrons, as shown by group-theoretical considerations. Aspherical deviations might be elicited for instance in crystals, where large crystal-electrical fields may occur at low-symmetry lattice sites. Significant ellipsoidal deformations have been shown to occur for sulfur ions and chalcogen ions in pyrite-type compounds.

Atomic dimensions are thousands of times smaller than the wavelengths of light (400–700 nm) so they cannot be viewed using an optical microscope. However, individual atoms can be observed using a scanning tunneling microscope. To visualize the minuteness of the atom, consider that a typical human hair is about 1 million carbon atoms in width. A single drop of water contains about 2 sextillion (2×1021) atoms of oxygen, and twice the number of hydrogen atoms. A single carat diamond with a mass of 2×10−4 kg contains about 10 sextillion (1022) atoms of carbon.

If an apple were magnified to the size of the Earth, then the atoms in

the apple would be approximately the size of the original apple.

Radioactive decay

This diagram shows the half-life (T½) of various isotopes with Z protons and N neutrons.

Every element has one or more isotopes that have unstable nuclei that

are subject to radioactive decay, causing the nucleus to emit particles

or electromagnetic radiation. Radioactivity can occur when the radius

of a nucleus is large compared with the radius of the strong force,

which only acts over distances on the order of 1 fm.

The most common forms of radioactive decay are:

- Alpha decay: this process is caused when the nucleus emits an alpha particle, which is a helium nucleus consisting of two protons and two neutrons. The result of the emission is a new element with a lower atomic number.

- Beta decay (and electron capture): these processes are regulated by the weak force, and result from a transformation of a neutron into a proton, or a proton into a neutron. The neutron to proton transition is accompanied by the emission of an electron and an antineutrino, while proton to neutron transition (except in electron capture) causes the emission of a positron and a neutrino. The electron or positron emissions are called beta particles. Beta decay either increases or decreases the atomic number of the nucleus by one. Electron capture is more common than positron emission, because it requires less energy. In this type of decay, an electron is absorbed by the nucleus, rather than a positron emitted from the nucleus. A neutrino is still emitted in this process, and a proton changes to a neutron.

- Gamma decay: this process results from a change in the energy level of the nucleus to a lower state, resulting in the emission of electromagnetic radiation. The excited state of a nucleus which results in gamma emission usually occurs following the emission of an alpha or a beta particle. Thus, gamma decay usually follows alpha or beta decay.

Other more rare types of radioactive decay include ejection of neutrons or protons or clusters of nucleons from a nucleus, or more than one beta particle. An analog of gamma emission which allows excited nuclei to lose energy in a different way, is internal conversion—a

process that produces high-speed electrons that are not beta rays,

followed by production of high-energy photons that are not gamma rays. A

few large nuclei explode into two or more charged fragments of varying

masses plus several neutrons, in a decay called spontaneous nuclear fission.

Each radioactive isotope has a characteristic decay time period—the half-life—that is determined by the amount of time needed for half of a sample to decay. This is an exponential decay

process that steadily decreases the proportion of the remaining isotope

by 50% every half-life. Hence after two half-lives have passed only 25%

of the isotope is present, and so forth.

Magnetic moment

Elementary particles possess an intrinsic quantum mechanical property known as spin. This is analogous to the angular momentum of an object that is spinning around its center of mass,

although strictly speaking these particles are believed to be

point-like and cannot be said to be rotating. Spin is measured in units

of the reduced Planck constant (ħ), with electrons, protons and neutrons all having spin ½ ħ, or "spin-½". In an atom, electrons in motion around the nucleus possess orbital angular momentum in addition to their spin, while the nucleus itself possesses angular momentum due to its nuclear spin.

The magnetic field produced by an atom—its magnetic moment—is

determined by these various forms of angular momentum, just as a

rotating charged object classically produces a magnetic field. However,

the most dominant contribution comes from electron spin. Due to the

nature of electrons to obey the Pauli exclusion principle, in which no two electrons may be found in the same quantum state,

bound electrons pair up with each other, with one member of each pair

in a spin up state and the other in the opposite, spin down state. Thus

these spins cancel each other out, reducing the total magnetic dipole

moment to zero in some atoms with even number of electrons.

In ferromagnetic

elements such as iron, cobalt and nickel, an odd number of electrons

leads to an unpaired electron and a net overall magnetic moment. The

orbitals of neighboring atoms overlap and a lower energy state is

achieved when the spins of unpaired electrons are aligned with each

other, a spontaneous process known as an exchange interaction. When the magnetic moments of ferromagnetic atoms are lined up, the material can produce a measurable macroscopic field. Paramagnetic materials

have atoms with magnetic moments that line up in random directions when

no magnetic field is present, but the magnetic moments of the

individual atoms line up in the presence of a field.

The nucleus of an atom will have no spin when it has even numbers

of both neutrons and protons, but for other cases of odd numbers, the

nucleus may have a spin. Normally nuclei with spin are aligned in random

directions because of thermal equilibrium. However, for certain elements (such as xenon-129) it is possible to polarize a significant proportion of the nuclear spin states so that they are aligned in the same direction—a condition called hyperpolarization. This has important applications in magnetic resonance imaging.

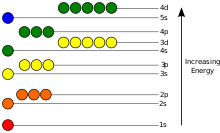

Energy levels

These electron's energy levels (not to scale) are sufficient for ground states of atoms up to cadmium (5s2 4d10) inclusively. Do not forget that even the top of the diagram is lower than an unbound electron state.

The potential energy of an electron in an atom is negative, its dependence of its position reaches the minimum (the most absolute value) inside the nucleus, and vanishes when the distance from the nucleus goes to infinity, roughly in an inverse proportion to the distance. In the quantum-mechanical model, a bound electron can only occupy a set of states centered on the nucleus, and each state corresponds to a specific energy level. An energy level can be measured by the amount of energy needed to unbind the electron from the atom, and is usually given in units of electronvolts (eV). The lowest energy state of a bound electron is called the ground state, i.e. stationary state, while an electron transition to a higher level results in an excited state. The electron's energy raises when n increases because the (average) distance to the nucleus increases. Dependence of the energy on ℓ is caused not by electrostatic potential of the nucleus, but by interaction between electrons.

For an electron to transition between two different states, e.g. ground state to first excited state, it must absorb or emit a photon at an energy matching the difference in the potential energy of those levels, according to the Niels Bohr model, what can be precisely calculated by the Schrödinger equation.

Electrons jump between orbitals in a particle-like fashion. For example,

if a single photon strikes the electrons, only a single electron

changes states in response to the photon; see Electron properties.

The energy of an emitted photon is proportional to its frequency, so these specific energy levels appear as distinct bands in the electromagnetic spectrum.

Each element has a characteristic spectrum that can depend on the

nuclear charge, subshells filled by electrons, the electromagnetic

interactions between the electrons and other factors.

An example of absorption lines in a spectrum

When a continuous spectrum of energy

is passed through a gas or plasma, some of the photons are absorbed by

atoms, causing electrons to change their energy level. Those excited

electrons that remain bound to their atom spontaneously emit this energy

as a photon, traveling in a random direction, and so drop back to lower

energy levels. Thus the atoms behave like a filter that forms a series

of dark absorption bands

in the energy output. (An observer viewing the atoms from a view that

does not include the continuous spectrum in the background, instead sees

a series of emission lines from the photons emitted by the atoms.) Spectroscopic measurements of the strength and width of atomic spectral lines allow the composition and physical properties of a substance to be determined.

Close examination of the spectral lines reveals that some display a fine structure splitting. This occurs because of spin–orbit coupling, which is an interaction between the spin and motion of the outermost electron.

When an atom is in an external magnetic field, spectral lines become

split into three or more components; a phenomenon called the Zeeman effect.

This is caused by the interaction of the magnetic field with the

magnetic moment of the atom and its electrons. Some atoms can have

multiple electron configurations

with the same energy level, which thus appear as a single spectral

line. The interaction of the magnetic field with the atom shifts these

electron configurations to slightly different energy levels, resulting

in multiple spectral lines. The presence of an external electric field

can cause a comparable splitting and shifting of spectral lines by

modifying the electron energy levels, a phenomenon called the Stark effect.

If a bound electron is in an excited state, an interacting photon with the proper energy can cause stimulated emission

of a photon with a matching energy level. For this to occur, the

electron must drop to a lower energy state that has an energy difference

matching the energy of the interacting photon. The emitted photon and

the interacting photon then move off in parallel and with matching

phases. That is, the wave patterns of the two photons are synchronized.

This physical property is used to make lasers, which can emit a coherent beam of light energy in a narrow frequency band.

Valence and bonding behavior

Valency is the combining power of an element. It is equal to number

of hydrogen atoms that atom can combine or displace in forming

compounds. The outermost electron shell of an atom in its uncombined state is known as the valence shell, and the electrons in

that shell are called valence electrons. The number of valence electrons determines the bonding

behavior with other atoms. Atoms tend to chemically react with each other in a manner that fills (or empties) their outer valence shells.

For example, a transfer of a single electron between atoms is a useful

approximation for bonds that form between atoms with one-electron more

than a filled shell, and others that are one-electron short of a full

shell, such as occurs in the compound sodium chloride

and other chemical ionic salts. However, many elements display multiple

valences, or tendencies to share differing numbers of electrons in

different compounds. Thus, chemical bonding

between these elements takes many forms of electron-sharing that are

more than simple electron transfers. Examples include the element carbon

and the organic compounds.

The chemical elements are often displayed in a periodic table

that is laid out to display recurring chemical properties, and elements

with the same number of valence electrons form a group that is aligned

in the same column of the table. (The horizontal rows correspond to the

filling of a quantum shell of electrons.) The elements at the far right

of the table have their outer shell completely filled with electrons,

which results in chemically inert elements known as the noble gases.

States

Graphic illustrating the formation of a Bose–Einstein condensate

Quantities of atoms are found in different states of matter that depend on the physical conditions, such as temperature and pressure. By varying the conditions, materials can transition between solids, liquids, gases and plasmas. Within a state, a material can also exist in different allotropes. An example of this is solid carbon, which can exist as graphite or diamond. Gaseous allotropes exist as well, such as dioxygen and ozone.

At temperatures close to absolute zero, atoms can form a Bose–Einstein condensate,

at which point quantum mechanical effects, which are normally only

observed at the atomic scale, become apparent on a macroscopic scale. This super-cooled collection of atoms

then behaves as a single super atom, which may allow fundamental checks of quantum mechanical behavior.

Identification

Scanning tunneling microscope image showing the individual atoms making up this gold (100) surface. The surface atoms deviate from the bulk crystal structure and arrange in columns several atoms wide with pits between them.

The scanning tunneling microscope is a device for viewing surfaces at the atomic level. It uses the quantum tunneling

phenomenon, which allows particles to pass through a barrier that would

normally be insurmountable. Electrons tunnel through the vacuum between

two planar metal electrodes, on each of which is an adsorbed

atom, providing a tunneling-current density that can be measured.

Scanning one atom (taken as the tip) as it moves past the other (the

sample) permits plotting of tip displacement versus lateral separation

for a constant current. The calculation shows the extent to which

scanning-tunneling-microscope images of an individual atom are visible.

It confirms that for low bias, the microscope images the space-averaged

dimensions of the electron orbitals across closely packed energy

levels—the Fermi level local density of states.

An atom can be ionized by removing one of its electrons. The electric charge causes the trajectory of an atom to bend when it passes through a magnetic field. The radius by which the trajectory of a moving ion is turned by the magnetic field is determined by the mass of the atom. The mass spectrometer uses this principle to measure the mass-to-charge ratio

of ions. If a sample contains multiple isotopes, the mass spectrometer

can determine the proportion of each isotope in the sample by measuring

the intensity of the different beams of ions. Techniques to vaporize

atoms include inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, both of which use a plasma to vaporize samples for analysis.

A more area-selective method is electron energy loss spectroscopy, which measures the energy loss of an electron beam within a transmission electron microscope when it interacts with a portion of a sample. The atom-probe tomograph has sub-nanometer resolution in 3-D and can chemically identify individual atoms using time-of-flight mass spectrometry.

Spectra of excited states can be used to analyze the atomic composition of distant stars. Specific light wavelengths

contained in the observed light from stars can be separated out and

related to the quantized transitions in free gas atoms. These colors can

be replicated using a gas-discharge lamp containing the same element. Helium was discovered in this way in the spectrum of the Sun 23 years before it was found on Earth.

Origin and current state

Baryonic matter forms about 4% of the total energy density of the observable Universe, with an average density of about 0.25 particles/m3 (mostly protons and electrons). Within a galaxy such as the Milky Way, particles have a much higher concentration, with the density of matter in the interstellar medium (ISM) ranging from 105 to 109 atoms/m3. The Sun is believed to be inside the Local Bubble, so the density in the solar neighborhood is only about 103 atoms/m3.

Stars form from dense clouds in the ISM, and the evolutionary processes

of stars result in the steady enrichment of the ISM with elements more

massive than hydrogen and helium.

Up to 95% of the Milky Way's baryonic matter are concentrated

inside stars, where conditions are unfavorable for atomic matter. The

total baryonic mass is about 10% of the mass of the galaxy; the remainder of the mass is an unknown dark matter. High temperature inside stars makes most "atoms" fully ionized, that is, separates all electrons from the nuclei. In stellar remnants—with exception of their surface layers—an immense pressure make electron shells impossible.

Formation

Electrons are thought to exist in the Universe since early stages of the Big Bang. Atomic nuclei forms in nucleosynthesis reactions. In about three minutes Big Bang nucleosynthesis produced most of the helium, lithium, and deuterium in the Universe, and perhaps some of the beryllium and boron.

Ubiquitousness and stability of atoms relies on their binding energy, which means that an atom has a lower energy than an unbound system of the nucleus and electrons. Where the temperature is much higher than ionization potential, the matter exists in the form of plasma—a

gas of positively charged ions (possibly, bare nuclei) and electrons.

When the temperature drops below the ionization potential, atoms become statistically favorable. Atoms (complete with bound electrons) became to dominate over charged particles 380,000 years after the Big Bang—an epoch called recombination, when the expanding Universe cooled enough to allow electrons to become attached to nuclei.

Since the Big Bang, which produced no carbon or heavier elements, atomic nuclei have been combined in stars through the process of nuclear fusion to produce more of the element helium, and (via the triple alpha process) the sequence of elements from carbon up to iron.

Isotopes such as lithium-6, as well as some beryllium and boron are generated in space through cosmic ray spallation. This occurs when a high-energy proton strikes an atomic nucleus, causing large numbers of nucleons to be ejected.

Elements heavier than iron were produced in supernovae through the r-process and in AGB stars through the s-process, both of which involve the capture of neutrons by atomic nuclei. Elements such as lead formed largely through the radioactive decay of heavier elements.

Earth

Most of the atoms that make up the Earth and its inhabitants were present in their current form in the nebula that collapsed out of a molecular cloud to form the Solar System. The rest are the result of radioactive decay, and their relative proportion can be used to determine the age of the Earth through radiometric dating. Most of the helium in the crust of the Earth (about 99% of the helium from gas wells, as shown by its lower abundance of helium-3) is a product of alpha decay.

There are a few trace atoms on Earth that were not present at the

beginning (i.e., not "primordial"), nor are results of radioactive

decay. Carbon-14 is continuously generated by cosmic rays in the atmosphere. Some atoms on Earth have been artificially generated either deliberately or as by-products of nuclear reactors or explosions. Of the transuranic elements—those with atomic numbers greater than 92—only plutonium and neptunium occur naturally on Earth. Transuranic elements have radioactive lifetimes shorter than the current age of the Earth and thus identifiable quantities of these elements have long since decayed, with the exception of traces of plutonium-244 possibly deposited by cosmic dust. Natural deposits of plutonium and neptunium are produced by neutron capture in uranium ore.

The Earth contains approximately 1.33×1050 atoms. Although small numbers of independent atoms of noble gases exist, such as argon, neon, and helium, 99% of the atmosphere is bound in the form of molecules, including carbon dioxide and diatomic oxygen and nitrogen. At the surface of the Earth, an overwhelming majority of atoms combine to form various compounds, including water, salt, silicates and oxides. Atoms can also combine to create materials that do not consist of discrete molecules, including crystals and liquid or solid metals.

This atomic matter forms networked arrangements that lack the

particular type of small-scale interrupted order associated with

molecular matter.

Rare and theoretical forms

Superheavy elements

While isotopes with atomic numbers higher than lead (82) are known to be radioactive, an "island of stability" has been proposed for some elements with atomic numbers above 103. These superheavy elements may have a nucleus that is relatively stable against radioactive decay. The most likely candidate for a stable superheavy atom, unbihexium, has 126 protons and 184 neutrons.

Exotic matter

Each particle of matter has a corresponding antimatter particle with the opposite electrical charge. Thus, the positron is a positively charged antielectron and the antiproton is a negatively charged equivalent of a proton.

When a matter and corresponding antimatter particle meet, they

annihilate each other. Because of this, along with an imbalance between

the number of matter and antimatter particles, the latter are rare in

the universe. The first causes of this imbalance are not yet fully

understood, although theories of baryogenesis may offer an explanation. As a result, no antimatter atoms have been discovered in nature. However, in 1996 the antimatter counterpart of the hydrogen atom (antihydrogen) was synthesized at the CERN laboratory in Geneva.

Other exotic atoms

have been created by replacing one of the protons, neutrons or

electrons with other particles that have the same charge. For example,

an electron can be replaced by a more massive muon, forming a muonic atom. These types of atoms can be used to test the fundamental predictions of physics.