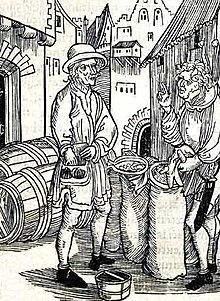

Of Usury, from Brant's Stultifera Navis (Ship of Fools), 1494; woodcut attributed to Albrecht Dürer

Usury is the practice of making unethical or immoral monetary loans

that unfairly enrich the lender. The term may be used in a moral

sense—condemning, taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal

sense, where an interest rate is charged in excess of the maximum rate

that is allowed by law. A loan may be considered usurious because of

excessive or abusive interest rates or other factors defined by a nation's laws. Someone who practices usury can be called a usurer, but in contemporary English may be called a loan shark.

Originally, usury meant the charging of interest

of any kind and, in some Christian societies and even today in many

Islamic societies, charging any interest at all was considered usury.

During the Sutra period in India (7th to 2nd centuries BC) there were

laws prohibiting the highest castes from practicing usury. Similar condemnations are found in religious texts from Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (the term is riba in Arabic and ribbit in Hebrew).

At times, many nations from ancient Greece to ancient Rome have

outlawed loans with any interest. Though the Roman Empire eventually

allowed loans with carefully restricted interest rates, the Catholic

Church in medieval Europe banned the charging of interest at any rate

(as well as charging a fee for the use of money, such as at a bureau de change). Religious prohibitions on usury are predicated upon the belief that charging interest on a loan is a sin.

History

Usury

(in the original sense of any interest) was at times denounced by a

number of religious leaders and philosophers in the ancient world,

including Moses, Plato, Aristotle, Cato, Cicero, Seneca, Aquinas, Muhammad, and Gautama Buddha.

Certain negative historical renditions of usury carry with them

social connotations of perceived "unjust" or "discriminatory" lending

practices. The historian Paul Johnson, comments:

Most early religious systems in the ancient Near East, and the secular codes arising from them, did not forbid usury. These societies regarded inanimate matter as alive, like plants, animals and people, and capable of reproducing itself. Hence if you lent 'food money', or monetary tokens of any kind, it was legitimate to charge interest. Food money in the shape of olives, dates, seeds or animals was lent out as early as c. 5000 BC, if not earlier. ...Among the Mesopotamians, Hittites, Phoenicians and Egyptians, interest was legal and often fixed by the state. But the Hebrew took a different view of the matter.

Theological historian John Noonan

argues that "the doctrine [of usury] was enunciated by popes, expressed

by three ecumenical councils, proclaimed by bishops, and taught

unanimously by theologians."

Roman Empire

Banking during the Roman Empire was different from modern banking. During the Principate, most banking activities were conducted by private individuals

who operated as large banking firms do today. Anybody that had any

available liquid assets and wished to lend it out could easily do so.

The annual rates of interest on loans varied in the range of 4–12

percent, but when the interest rate was higher, it typically was not

15–16 percent but either 24 percent or 48 percent. They quoted them on a

monthly basis, and the most common rates were multiples of twelve.

Monthly rates tended to range from simple fractions to 3–4 percent,

perhaps because lenders used Roman numerals.

Money lending during this period was largely a matter of private

loans advanced to persons persistently in debt or temporarily so until

harvest time. Mostly, it was undertaken by exceedingly rich men prepared

to take on a high risk if the profit looked good; interest rates were

fixed privately and were almost entirely unrestricted by law. Investment

was always regarded as a matter of seeking personal profit, often on a

large scale. Banking was of the small, back-street variety, run by the

urban lower-middle class of petty shopkeepers. By the 3rd century, acute

currency problems in the Empire drove such banking into decline.

The rich who were in a position to take advantage of the situation

became the moneylenders when the increasing tax demands in the last

declining days of the Empire crippled and eventually destroyed the

peasant class by reducing tenant-farmers to serfs. It was evident that usury meant exploitation of the poor.

Cicero, in the second book of his treatise De Officiis, relates the following conversation between an unnamed questioner and Cato:

...of whom, when inquiry was made, what was the best policy in the management of one's property, he answered "Good grazing." "What was next?" "Tolerable grazing." "What third?" "Bad grazing." "What fourth?" "Tilling." And when he who had interrogated him inquired, "What do you think of lending at usury?" Then Cato answered, "What do you think of murder?"

Judaism

Jews are forbidden from usury in dealing with fellow Jews, and this lending is to be considered tzedakah, or charity. However, there are permissions to charge interest on loans to non-Jews. This is outlined in the Jewish scriptures of the Torah, which Christians hold as part of the Old Testament, and other books of the Tanakh.

If thou lend money to any of My people, even to the poor with thee, thou shalt not be to him as a creditor; neither shall ye lay upon him interest.

Take thou no interest of him or increase; but fear thy God; that thy brother may live with thee. Thou shalt not give him thy money upon interest, nor give him thy victuals for increase.

Thou shalt not lend upon interest to thy brother: interest of money, interest of victuals, interest of any thing that is lent upon interest. Unto a foreigner thou mayest lend upon interest; but unto thy brother thou shalt not lend upon interest; that the LORD thy God may bless thee in all that thou puttest thy hand unto, in the land whither thou goest in to possess it.

that hath withdrawn his hand from the poor, that hath not received interest nor increase, hath executed Mine ordinances, hath walked in My statutes; he shall not die for the iniquity of his father, he shall surely live.

In thee have they taken gifts to shed blood; thou hast taken interest and increase, and thou hast greedily gained of thy neighbours by oppression, and hast forgotten Me, saith the Lord GOD.

Then I consulted with myself, and contended with the nobles and the rulers, and said unto them: 'Ye lend upon pledge, every one to his brother.' And I held a great assembly against them.

He that putteth not out his money on interest, nor taketh a bribe against the innocent. He that doeth these things shall never be moved.

Johnson contends that the Torah treats lending as philanthropy in a poor community whose aim was collective survival, but which is not obliged to be charitable towards outsiders.

A great deal of Jewish legal scholarship in the Dark and the Middle Ages was devoted to making business dealings fair, honest and efficient.

As the Jews were ostracized from most professions by local rulers during the middle ages, the Western churches and the guilds, they were pushed into marginal occupations considered socially inferior, such as tax and rent

collecting and moneylending. Natural tensions between creditors and

debtors were added to social, political, religious, and economic

strains.

...financial oppression of Jews tended to occur in areas where they were most disliked, and if Jews reacted by concentrating on moneylending to non-Jews, the unpopularity—and so, of course, the pressure—would increase. Thus the Jews became an element in a vicious circle. The Christians, on the basis of the Biblical rulings, condemned interest-taking absolutely, and from 1179 those who practiced it were excommunicated. Catholic autocrats frequently imposed the harshest financial burdens on the Jews. The Jews reacted by engaging in the one business where Christian laws actually discriminated in their favor, and became identified with the hated trade of moneylending.

Several historical rulings in Jewish law have mitigated the allowances for usury toward non-Jews. For instance, the 15th-century commentator Rabbi Isaac Abrabanel

specified that the rubric for allowing interest does not apply to

Christians or Muslims, because their faith systems have a common ethical

basis originating from Judaism. The medieval commentator Rabbi David Kimchi

extended this principle to non-Jews who show consideration for Jews,

saying they should be treated with the same consideration when they

borrow.

England

In England, the departing Crusaders were joined by crowds of debtors in the massacres of Jews at London and York in 1189–1190. In 1275, Edward I of England passed the Statute of the Jewry which made usury illegal and linked it to blasphemy,

in order to seize the assets of the violators. Scores of English Jews

were arrested, 300 were hanged and their property went to the Crown.

In 1290, all Jews were to be expelled from England, allowed to take

only what they could carry; the rest of their property became the

Crown's. Usury was cited as the official reason for the Edict of Expulsion;

however, not all Jews were expelled: it was easy to avoid expulsion by

converting to Christianity. Many other crowned heads of Europe expelled

the Jews, although again converts to Christianity were no longer

considered Jewish. Many of these forced converts still secretly practiced their faith.

The growth of the Lombard bankers and pawnbrokers, who moved from city to city, was along the pilgrim routes.

Die Wucherfrage is the title of a Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod work against usury from 1869. Usury is condemned in 19th-century Missouri Synod doctrinal statements.

In the 16th century, short-term interest rates dropped dramatically

(from around 20–30% p.a. to around 9–10% p.a.). This was caused by

refined commercial techniques, increased capital availability, the Reformation,

and other reasons. The lower rates weakened religious scruples about

lending at interest, although the debate did not cease altogether.

The 18th century papal prohibition on usury meant that it was a sin to charge interest on a money loan. As set forth by Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century, the natural essence of money was as a measure of value or intermediary in exchange. The increase of money through usury violated this essence and according to the same Thomistic

analysis, a just transaction was one characterized by an equality of

exchange, one where each side received exactly his due. Interest on a

loan, in excess of the principal, would violate the balance of an

exchange between debtor and creditor and was therefore unjust.

Charles Eisenstein has argued that pivotal change in the English-speaking world came with lawful rights to charge interest on lent money, particularly the 1545 Act, "An Act Against Usurie" (37 Hen. VIII, c. 9) of King Henry VIII of England.

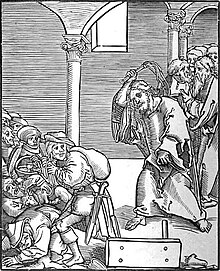

Christianity

Christ drives the Usurers out of the Temple, a woodcut by Lucas Cranach the Elder in Passionary of Christ and Antichrist.

Church councils

The First Council of Nicaea, in 325, forbade clergy from engaging in usury

Forasmuch as many enrolled among the Clergy, following covetousness and lust of gain, have forgotten the divine Scripture, which says, "He has not given his money upon usury" [Ezek. xviii, 8], and in lending money ask the hundredth of the sum [as monthly interest], the holy and great Synod thinks it just that if after this decree any one be found to receive usury, whether he accomplish it by secret transaction or otherwise, as by demanding the whole and one half, or by using any other contrivance whatever for filthy lucre's sake, he shall be deposed from the clergy and his name stricken from the list. (canon 17).

At the time, usury was interest of any kind, and the canon forbade the clergy to lend money at interest rates even as low as 1 percent per year. Later ecumenical councils applied this regulation to the laity.

Lateran III decreed that persons who accepted interest on loans could receive neither the sacraments nor Christian burial.

Nearly everywhere the crime of usury has become so firmly rooted that many, omitting other business, practise usury as if it were permitted, and in no way observe how it is forbidden in both the Old and New Testament. We therefore declare that notorious usurers should not be admitted to communion of the altar or receive christian burial if they die in this sin. Whoever receives them or gives them christian burial should be compelled to give back what he has received, and let him remain suspended from the performance of his office until he has made satisfaction according to the judgment of his own bishop. (canon 25)

The Council of Vienne made the belief in the right to usury a heresy in 1311, and condemned all secular legislation which allowed it.

Serious suggestions have been made to us that communities in certain places, to the divine displeasure and injury of the neighbour, in violation of both divine and human law, approve of usury. By their statutes, sometimes confirmed by oath, they not only grant that usury may be demanded and paid, but deliberately compel debtors to pay it. By these statutes they impose heavy burdens on those claiming the return of usurious payments, employing also various pretexts and ingenious frauds to hinder the return. We, therefore, wishing to get rid of these pernicious practices, decree with the approval of the sacred council that all the magistrates, captains, rulers, consuls, judges, counsellors or any other officials of these communities who presume in the future to make, write or dictate such statutes, or knowingly decide that usury be paid or, if paid, that it be not fully and freely restored when claimed, incur the sentence of excommunication. They shall also incur the same sentence unless within three months they delete from the books of their communities, if they have the power, statutes of this kind hitherto published, or if they presume to observe in any way these statutes or customs. Furthermore, since money-lenders for the most part enter into usurious contracts so frequently with secrecy and guile that they can be convicted only with difficulty, we decree that they be compelled by ecclesiastical censure to open their account books, when there is question of usury. If indeed someone has fallen into the error of presuming to affirm pertinaciously that the practice of usury is not sinful, we decree that he is to be punished as a heretic; and we strictly enjoin on local ordinaries and inquisitors of heresy to proceed against those they find suspect of such error as they would against those suspected of heresy. (canon 29)

Up to the 16th century, usury was condemned by the Catholic Church, but not really defined. During the Fifth Lateran Council, in the 10th session (in the year 1515), the Council for the first time gave a definition of usury:

For, that is the real meaning of usury: when, from its use, a thing which produces nothing is applied to the acquiring of gain and profit without any work, any expense or any risk.

The Fifth Lateran Concil, in the same declaration, gave explicit approval of charging interest in the case of Mounts of Piety:

(...) We declare and define, with the approval of the Sacred Council, that the above-mentioned credit organisations, established by states and hitherto approved and confirmed by the authority of the Apostolic See, do not introduce any kind of evil or provide any incentive to sin if they receive, in addition to the capital, a moderate sum for their expenses and by way of compensation, provided it is intended exclusively to defray the expenses of those employed and of other things pertaining (as mentioned) to the upkeep of the organizations, and provided that no profit is made therefrom. They ought not, indeed, to be condemned in any way. Rather, such a type of lending is meritorious and should be praised and approved. It certainly should not be considered as usurious; (...)

Pope Sixtus V

condemned the practice of charging interest as "detestable to God and

man, damned by the sacred canons, and contrary to Christian charity.

Medieval Theology

The first of the scholastic Christian theologians, Saint Anselm of Canterbury, led the shift in thought that labelled charging interest the same as theft. Previously usury had been seen as a lack of charity.

St. Thomas Aquinas, the leading scholastic theologian of the Roman Catholic Church,

argued charging of interest is wrong because it amounts to "double

charging", charging for both the thing and the use of the thing. Aquinas

said this would be morally wrong in the same way as if one sold a

bottle of wine, charged for the bottle of wine, and then charged for the

person using the wine to actually drink it.

Similarly, one cannot charge for a piece of cake and for the eating of

the piece of cake. Yet this, said Aquinas, is what usury does. Money is a

medium of exchange, and is used up when it is spent. To charge for the

money and for its use (by spending) is therefore to charge for the money

twice. It is also to sell time since the usurer charges, in effect, for

the time that the money is in the hands of the borrower. Time, however,

is not a commodity for which anyone can charge. In condemning usury

Aquinas was much influenced by the recently rediscovered philosophical

writings of Aristotle and his desire to assimilate Greek philosophy with Christian theology.

Aquinas argued that in the case of usury, as in other aspects of

Christian revelation, Christian doctrine is reinforced by Aristotelian natural law

rationalism. Aristotle's argument is that interest is unnatural, since

money, as a sterile element, cannot naturally reproduce itself. Thus,

usury conflicts with natural law just as it offends Christian

revelation: see Thought of Thomas Aquinas.

Outlawing usury did not prevent investment, but stipulated that

in order for the investor to share in the profit he must share the risk.

In short he must be a joint-venturer. Simply to invest the money and

expect it to be returned regardless of the success of the venture was to

make money simply by having money and not by taking any risk or by

doing any work or by any effort or sacrifice at all, which is usury. St

Thomas quotes Aristotle as saying that "to live by usury is exceedingly

unnatural". Islam likewise condemns usury but allowed commerce

(Al-Baqarah 2:275) - an alternative that suggests investment and sharing

of profit and loss instead of sharing only profit through interests.

Judaism condemns usury towards Jews, but allows it towards non-Jews.

(Deut 23:19-20)

St Thomas allows, however, charges for actual services provided. Thus a

banker or credit-lender could charge for such actual work or effort as

he did carry out e.g. any fair administrative charges. The Catholic

Church, in a decree of the Fifth Council of the Lateran, expressly allowed such charges in respect of credit-unions run for the benefit of the poor known as "montes pietatis".

In the 13th century Cardinal Hostiensis enumerated thirteen situations in which charging interest was not immoral. The most important of these was lucrum cessans

(profits given up) which allowed for the lender to charge interest "to

compensate him for profit foregone in investing the money himself." (Rothbard 1995,

p. 46) This idea is very similar to opportunity cost. Many scholastic

thinkers who argued for a ban on interest charges also argued for the

legitimacy of lucrum cessans profits (e.g. Pierre Jean Olivi and St. Bernardino of Siena). However, Hostiensis' exceptions, including for lucrum cessans, were never accepted as official by the Roman Catholic Church.

Pope Benedict XIV's encyclical Vix Pervenit, operating in the pre-industrial mindset, gives the reasons why usury is sinful:

The nature of the sin called usury has its proper place and origin in a loan contract… [which] demands, by its very nature, that one return to another only as much as he has received. The sin rests on the fact that sometimes the creditor desires more than he has given…, but any gain which exceeds the amount he gave is illicit and usurious.

One cannot condone the sin of usury by arguing that the gain is not great or excessive, but rather moderate or small; neither can it be condoned by arguing that the borrower is rich; nor even by arguing that the money borrowed is not left idle, but is spent usefully…

Usury controversies in 15th through 19th century Catholicism

Concerns about usury included the 19th century Rothschild loans to the Holy See and 16th century concerns over abuse of the zinskauf clause. This was problematic because the charging of interest (although not all interest - see above for Fifth Lateran Council) can be argumented to be a violation of doctrine at the time, such as that reflected in the 1745 encyclical Vix pervenit. To prevent any claims of doctrine violation, work-arounds would sometimes be employed. For example, in the 15th century, the Medici Bank

lent money to the Vatican, which was lax about repayment. Rather than

charging interest, "the Medici overcharged the pope on the silks and

brocades, the jewels and other commodities they supplied." However, the 1917 Code of Canon Law switched position and allowed church monies to be used to accrue interest.

It can be proposed that the Catholic Church has not, since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution,

changed its interpretation of practical matters of interest but that it

only fails to enforce the rules, perhaps out of the fear of a greater

evil. Yet, this view fails to take into account the very practical

consequences of an explosion of innovation and commerce, necessitating

soul-searching in all social participants.

The Roman Catholic Church has always condemned usury, but in modern times, with the rise of capitalism,

the previous assumptions about the very nature of money got challenged,

and the Catholic Church had to update its understanding of what

constitutes usury to also include the new reality. Thus, the Church refers, among other things, to the fact Mosaic Law doesn't ban all interest taking (proving interest-taking is not an inherently immoral act, same principle as with homicide),

as well as the fact that we can now do more with money then just spend

it. There are today many opportunities for investment, risk taking and

commerce in general where just 200 years ago there were very few

options. In the days of St. Aquinas,

one had the options of either spending or hoarding the money. Today,

(almost) anyone can either spend, hoard, invest, speculate or lend to

businesses or persons. Because of this, as the old Catholic Encyclopedia

put it, "Since the possession of an object is generally useful, I may

require the price of that general utility, even when the object is of no

use to me."

Jesuit philosopher Joseph Rickaby, writing at the beginning of the 20th century, put the development of economy in relation to usury this way:

In great cities commerce rapidly ripened, and was well on towards maturity five centuries ago. Then the conditions that render interest lawful, and mark if off from usury, readily came to obtain. But those centres were isolated. (...) Here you might have a great city, Hamburg or Genoa, an early type of commercial enterprise, and, fifty miles inland, society was in infancy, and the great city was as part of another world. Hence the same transaction, as described by the letter of the law, might mean lawful interest in the city, and usury out in the country - the two were so disconnected.

He further gave the following view of the development of Catholic practice:

In such a situation the legislator has to choose between forbidding interest here and allowing usury there; between restraining speculation and licensing oppression. The mediaeval legislator chose the former alternative. Church and State together enacted a number of laws to restrain the taking of interest, laws that, like the clothes of infancy, are not to be scorned as absurd restrictions, merely because they are inapplicable now, and would not fit the modern growth of nations. At this day the State has repealed those laws, and the Church has officially signified that she no longer insists on them. Still she maintains dogmatically that there is such a sin as usury, and what it is, as defined in the Fifth Council of Lateran.

Islam

Interest of any kind is forbidden in Islam. As such, specialized

codes of banking have developed to cater to investors wishing to obey Qur'anic law.

The following quotations are English translations from the Qur'an:

Those who charge usury are in the same position as those controlled by the devil's influence. This is because they claim that usury is the same as commerce. However, God permits commerce, and prohibits usury. Thus, whoever heeds this commandment from his Lord, and refrains from usury, he may keep his past earnings, and his judgment rests with God. As for those who persist in usury, they incur Hell, wherein they abide forever (Al-Baqarah 2:275)

God condemns usury, and blesses charities. God dislikes every sinning disbeliever. Those who believe and do good works and establish worship and pay the poor-due, their reward is with their Lord and there shall no fear come upon them neither shall they grieve. O you who believe, you shall observe God and refrain from all kinds of usury, if you are believers. If you do not, then expect a war from God and His messenger. But if you repent, you may keep your capitals, without inflicting injustice, or incurring injustice. If the debtor is unable to pay, wait for a better time. If you give up the loan as a charity, it would be better for you, if you only knew. (Al-Baqarah 2:276-280)

O you who believe, you shall not take usury, compounded over and over. Observe God, that you may succeed. (Al-'Imran 3:130)

And for practicing usury, which was forbidden, and for consuming the people's money illicitly. We have prepared for the disbelievers among them painful retribution. (Al-Nisa 4:161)

The usury that is practiced to increase some people's wealth, does not gain anything at God. But if people give to charity, seeking God's pleasure, these are the ones who receive their reward many fold. (Ar-Rum 30:39)

The attitude of Muhammad to usury is articulated in his Last Sermon:

O People, just as you regard this month, this day, this city as Sacred, so regard the life and property of every Muslim as a sacred trust. Return the goods entrusted to you to their rightful owners. Hurt no one so that no one may hurt you. Remember that you will indeed meet your LORD, and that HE will indeed reckon your deeds. ALLAH has forbidden you to take usury, therefore all usurious obligation shall henceforth be waived. Your capital, however, is yours to keep. You will neither inflict nor suffer any inequity. Allah has Judged that there shall be no usury and that all the usury due to Abbas ibn 'Abd'al Muttalib (Prophet's uncle) shall henceforth be waived...

In literature

In The Divine Comedy, Dante places the usurers in the inner ring of the seventh circle of hell.

Interest on loans, and the contrasting views on the morality of

that practice held by Jews and Christians, is central to the plot of

Shakespeare's play "The Merchant of Venice". Antonio is the merchant of the title, a Christian, who is forced by circumstance to borrow money from Shylock,

a Jew. Shylock customarily charges interest on loans, seeing it as good

business, while Antonio does not, viewing it as morally wrong. When

Antonio defaults on his loan, Shylock famously demands the agreed upon

penalty: a measured quantity of muscle from Antonio's chest. This is the

source of the metaphorical phrase "a pound of flesh" often used to

describe the dear price of a loan or business transaction. Shakespeare's

play is a vivid portrait of the competing views of loans and use of

interest, as well as the cultural strife between Jews and Christians

that overlaps it.

By the 18th century, usury was more often treated as a metaphor than a crime in itself, so Jeremy Bentham's Defense of Usury was not as shocking as it would have appeared two centuries earlier.

In Honoré de Balzac's 1830 novel Gobseck, the title character, who is a usurer, is described as both "petty and great—a miser and a philosopher..." The character Daniel Quilp in The Old Curiosity Shop by Charles Dickens is a usurer.

In the early 20th century Ezra Pound's anti-usury poetry was not primarily based on the moral injustice of interest payments but on the fact that excess capital was no longer devoted to artistic patronage, as it could now be used for capitalist business investment.

Usury law

Usury and the law

Magna Carta

commands, "If any one has taken anything, whether much or little, by

way of loan from Jews, and if he dies before that debt is paid, the debt

shall not carry usury so long as the heir is under age, from whomsoever

he may hold. And if that debt falls into our hands, we will take only

the principal contained in the note."

"When money is lent on a contract to receive not only the principal

sum again, but also an increase by way of compensation for the use, the

increase is called interest by those who think it lawful, and usury by those who do not." (William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England).

Canada

Canada's Criminal Code limits the interest rate to 60% per year.

The law is broadly written and Canada's courts have often intervened to remove ambiguity.

Japan

Japan has

various laws restricting interest rates. Under civil law, the maximum

interest rate is between 15% and 20% per year depending upon the

principal amount (larger amounts having a lower maximum rate). Interest

in excess of 20% is subject to criminal penalties (the criminal law

maximum was 29.2% until it was lowered by legislation in 2010). Default interest on late payments may be charged at up to 1.46 times the ordinary maximum (i.e., 21.9% to 29.2%), while pawn shops

may charge interest of up to 9% per month (i.e., 108% per year,

however, if the loan extends more than the normal short-term pawn shop

loan, the 9% per month rate compounded can make the annual rate in

excess of 180%, before then most of these transaction would result in

any goods pawned being forfeited).

United States

Usury laws are state laws that specify the maximum legal interest rate at which loans can be made. In the United States, the primary legal power to regulate usury rests primarily with the states. Each U.S. state has its own statute that dictates how much interest can be charged before it is considered usurious or unlawful.

If a lender charges above the lawful interest rate, a court will

not allow the lender to sue to recover the unlawfully high interest, and

some states will apply all payments made on the debt to the principal

balance. In some states, such as New York, usurious loans are voided ab initio.

The making of usurious loans is often called loan sharking.

That term is sometimes also applied to the practice of making consumer

loans without a license in jurisdictions that requires lenders to be

licensed.

Federal regulation

On

a federal level, Congress has never attempted to federally regulate

interest rates on purely private transactions, but on the basis of past

U.S. Supreme Court decisions, arguably the U.S. Congress might have the

power to do so under the interstate commerce clause of Article I of the Constitution.

Congress imposed a federal criminal penalty for unlawful interest rates through the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act

(RICO Statute), and its definition of "unlawful debt", which makes it a

potential federal felony to lend money at an interest rate more than

twice the local state usury rate and then try to collect that debt.

It is a federal offense to use violence or threats to collect usurious interest (or any other sort).

Separate federal rules apply to most banks. The U.S. Supreme Court held unanimously in the 1978 case, Marquette Nat. Bank of Minneapolis v. First of Omaha Service Corp., that the National Banking Act of 1863 allowed nationally chartered banks to charge the legal rate of interest in their state regardless of the borrower's state of residence.

In 1980, Congress passed the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act.

Among the Act's provisions, it exempted federally chartered savings

banks, installment plan sellers and chartered loan companies from state

usury limits. Combined with the Marquette decision that applied to National Banks, this effectively overrode all state and local usury laws. The 1968 Truth in Lending Act does not regulate rates, except for some mortgages, but requires uniform or standardized disclosure of costs and charges.

In the 1996 Smiley v. Citibank case, the Supreme Court further limited states' power to regulate credit card fees and extended the reach of the Marquette

decision. The court held that the word "interest" used in the 1863

banking law included fees and, therefore, states could not regulate

fees.

Some members of Congress have tried to create a federal usury

statute that would limit the maximum allowable interest rate, but the

measures have not progressed. In July 2010, the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, was signed into law by President Obama. The act provides for a Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to regulate some credit practices but has no interest rate limit.

Texas

State law

in Texas also includes a provision for contracting for, charging, or

receiving charges exceeding twice the amount authorized (A/K/A "double

usury"). A person who violates this provision is liable to the obligor

as an additional penalty for all principal or principal balance, as well

as interest or time price differential. A person who is liable is also

liable for reasonable attorney's fees incurred by the obligor.

Avoidance mechanisms and interest-free lending

Islamic banking

In a partnership or joint venture where money is lent, the creditor

only provides the capital yet is guaranteed a fixed amount of profit.

The debtor, however, puts in time and effort, but is made to bear the

risk of loss. Muslim scholars argue that such practice is unjust.

As an alternative to usury, Islam strongly encourages charity and

direct investment in which the creditor shares whatever profit or loss

the business may incur (in modern terms, this amounts to an equity stake

in the business).

Interest-free banks

The JAK members bank is a usury-free saving and loaning system.

Interest-free micro-lending

Growth of the Internet internationally has enabled both business micro-lending through sites such as Kickstarter as well as through global micro-lending

charities where lenders make small sums of money available on

zero-interest terms. Persons lending money to on-line micro-lending

charity Kiva for example do not get paid any interest,

although the end users to whom the loans are made may be charged

interest by Kiva's partners in the country where the loan is used.

Non-recourse mortgages

A non-recourse loan

is secured by the value of property (usually real estate) owned by the

debtor. However, unlike other loans, which oblige the debtor to repay

the amount borrowed, a non-recourse loan is fully satisfied merely by

the transfer of the property to the creditor, even if the property has

declined in value and is worth less than the amount borrowed. When such

a loan is created, the creditor bears the risk that the property will

decline sharply in value (in which case the creditor is repaid with

property worth less than the amount borrowed), and the debtor does not

bear the risk of decrease in property value (because the debtor is

guaranteed the right to use the property, regardless of value, to

satisfy the debt.)

Zinskauf

Zinskauf was used as an avoidance mechanism in the Middle Ages.