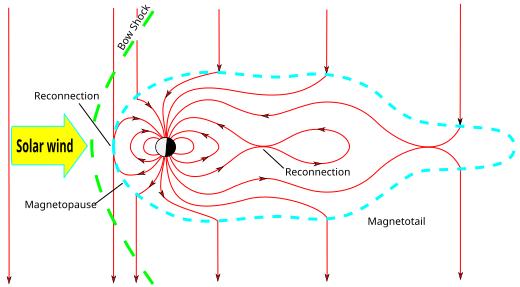

Artist's depiction of solar wind particles interacting with Earth's magnetosphere. Sizes are not to scale.

A geomagnetic storm (commonly referred to as a solar storm) is a temporary disturbance of the Earth's magnetosphere caused by a solar wind shock wave and/or cloud of magnetic field that interacts with the Earth's magnetic field.

The disturbance that drives the magnetic storm may be a solar coronal mass ejection (CME) or a co-rotating interaction region (CIR), a high-speed stream of solar wind originating from a coronal hole. The frequency of geomagnetic storms increases and decreases with the sunspot cycle. During solar maximum,

geomagnetic storms occur more often, with the majority driven by CMEs.

During solar minimum, storms are mainly driven by CIRs (though CIR

storms are more frequent at solar maximum than at minimum).

The increase in the solar wind pressure initially compresses the

magnetosphere. The solar wind's magnetic field interacts with the

Earth's magnetic field and transfers an increased energy into the

magnetosphere. Both interactions cause an increase in plasma movement

through the magnetosphere (driven by increased electric fields inside

the magnetosphere) and an increase in electric current in the

magnetosphere and ionosphere.

During the main phase of a geomagnetic storm, electric current in the

magnetosphere creates a magnetic force that pushes out the boundary

between the magnetosphere and the solar wind.

Several space weather phenomena tend to be associated with or are caused by a geomagnetic storm. These include solar energetic particle (SEP) events, geomagnetically induced currents

(GIC), ionospheric disturbances that cause radio and radar

scintillation, disruption of navigation by magnetic compass and auroral

displays at much lower latitudes than normal.

The largest recorded geomagnetic storm, the Carrington Event

in September 1859, took down parts of the recently created US telegraph

network, starting fires and shocking some telegraph operators. In 1989, a geomagnetic storm energized ground induced currents that disrupted electric power distribution throughout most of Quebec and caused aurorae as far south as Texas.

| Heliophysics |

|---|

| Phenomena |

Definition

A geomagnetic storm is defined by changes in the Dst

(disturbance – storm time) index. The Dst index estimates the globally

averaged change of the horizontal component of the Earth's magnetic

field at the magnetic equator based on measurements from a few

magnetometer stations. Dst is computed once per hour and reported in

near-real-time. During quiet times, Dst is between +20 and −20 nano-Tesla (nT).

A geomagnetic storm has three phases:

initial, main and recovery. The initial phase is characterized by Dst

(or its one-minute component SYM-H) increasing by 20 to 50 nT in tens of

minutes. The initial phase is also referred to as a storm sudden

commencement (SSC). However, not all geomagnetic storms have an initial

phase and not all sudden increases in Dst or SYM-H are followed by a

geomagnetic storm. The main phase of a geomagnetic storm is defined by

Dst decreasing to less than −50 nT. The selection of −50 nT to define a

storm is somewhat arbitrary. The minimum value during a storm will be

between −50 and approximately −600 nT. The duration of the main phase is

typically 2–8 hours. The recovery phase is when Dst changes from its

minimum value to its quiet time value. The recovery phase may last as

short as 8 hours or as long as 7 days.

The size of a geomagnetic storm is classified as moderate (−50 nT

> minimum of Dst > −100 nT), intense (−100 nT > minimum Dst

> −250 nT) or super-storm (minimum of Dst < −250 nT).[7]

History of Theory

In 1931, Sydney Chapman and Vincenzo C. A. Ferraro wrote an article, A New Theory of Magnetic Storms, that sought to explain the phenomenon.[8] They argued that whenever the Sun emits a solar flare it also emits a plasma cloud, now known as a coronal mass ejection. They postulated that this plasma

travels at a velocity such that it reaches Earth within 113 days,

though we now know this journey takes 1 to 5 days. They wrote that the

cloud then compresses the Earth's magnetic field and thus increases this field at the Earth's surface.[9]

Chapman and Ferraro's work drew on that of, among others, Kristian Birkeland, who had used recently discovered cathode ray tubes

to show that the rays were deflected towards the poles of a magnetic

sphere. He theorised that a similar phenomenon was responsible for

auroras, explaining why they are more frequent in polar regions.

Occurrences

The

first scientific observation of the effects of a geomagnetic storm

occurred early in the 19th century: From May 1806 until June 1807, Alexander von Humboldt recorded the bearing of a magnetic compass in Berlin. On 21 December 1806, he noticed that his compass had become erratic during a bright auroral event.[10]

On September 1–2, 1859, the largest recorded geomagnetic storm

occurred. From August 28 until September 2, 1859, numerous sunspots and

solar flares were observed on the Sun, with the largest flare on

September 1. This is referred to as the Solar storm of 1859 or the Carrington Event. It can be assumed that a massive coronal mass ejection

(CME) was launched from the Sun and reached the Earth within eighteen

hours—a trip that normally takes three to four days. The horizontal

field was reduced by 1600 nT as recorded by the Colaba Observatory. It is estimated that Dst would have been approximately −1760 nT.[11] Telegraph wires in both the United States and Europe experienced induced voltage increases (emf),

in some cases even delivering shocks to telegraph operators and

igniting fires. Aurorae were seen as far south as Hawaii, Mexico, Cuba

and Italy—phenomena that are usually only visible in polar regions. Ice cores show evidence that events of similar intensity recur at an average rate of approximately once per 500 years.

Since 1859, less severe storms have occurred, notably the aurora of November 17, 1882 and the May 1921 geomagnetic storm, both with disruption of telegraph service and initiation of fires, and 1960, when widespread radio disruption was reported.[12]

GOES-7

monitors the space weather conditions during the Great Geomagnetic

storm of March 1989, the Moscow neutron monitor recorded the passage of a

CME as a drop in levels known as a Forbush decrease.[13]

In early August 1972,

a series of flares and solar storms peaks with a flare estimated around

X20 producing the fastest CME transit ever recorded and a severe

geomagnetic and proton storm that disrupted terrestrial electrical and

communications networks, as well as satellites (at least one made

permanently inoperative), and unintentionally detonated numerous U.S.

Navy magnetic-influence sea mines in North Vietnam.[14]

The March 1989 geomagnetic storm caused the collapse of the Hydro-Québec power grid in seconds as equipment protection relays tripped in a cascading sequence.[2][15] Six million people were left without power for nine hours. The storm caused auroras as far south as Texas.[3] The storm causing this event was the result of a coronal mass ejected from the Sun on March 9, 1989.[16] The minimum of Dst was −589 nT.

On July 14, 2000, an X5 class flare erupted (known as the Bastille Day event)

and a coronal mass was launched directly at the Earth. A geomagnetic

super storm occurred on July 15–17; the minimum of the Dst index was

−301 nT. Despite the storm's strength, no power distribution failures

were reported.[17] The Bastille Day event was observed by Voyager 1 and Voyager 2,[18] thus it is the farthest out in the Solar System that a solar storm has been observed.

Seventeen major flares erupted on the Sun between 19 October and 5

November 2003, including perhaps the most intense flare ever measured

on the GOES XRS sensor—a huge X28 flare,[19]

resulting in an extreme radio blackout, on 4 November. These flares

were associated with CME events that caused three geomagnetic storms

between 29 October and 2 November, during which the second and third

storms were initiated before the previous storm period had fully

recovered. The minimum Dst values were −151, −353 and −383 nT. Another

storm in this sequence occurred on 4–5 November with a minimum Dst of

−69 nT. The last geomagnetic storm was weaker than the preceding storms,

because the active region on the Sun had rotated beyond the meridian

where the central portion CME created during the flare event passed to

the side of the Earth. The whole sequence became known as the Halloween Solar Storm.[20] The Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS) operated by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) was offline for approximately 30 hours due to the storm.[21]

The Japanese ADEOS-2 satellite was severely damaged and the operation

of many other satellites were interrupted due to the storm.[22]

Interactions with planetary processes

The solar wind also carries with it the Sun's magnetic field. This

field will have either a North or South orientation. If the solar wind

has energetic bursts, contracting and expanding the magnetosphere, or if

the solar wind takes a southward polarization, geomagnetic storms can be expected. The southward field causes magnetic reconnection of the dayside magnetopause, rapidly injecting magnetic and particle energy into the Earth's magnetosphere.

During a geomagnetic storm, the ionosphere's F2 layer becomes unstable, fragments, and may even disappear. In the northern and southern pole regions of the Earth, auroras are observable.

Instruments

Magnetometers monitor the auroral zone as well as the equatorial region. Two types of radar,

coherent scatter and incoherent scatter, are used to probe the auroral

ionosphere. By bouncing signals off ionospheric irregularities, which

move with the field lines, one can trace their motion and infer

magnetospheric convection.

Spacecraft instruments include:

- Magnetometers, usually of the flux gate type. Usually these are at the end of booms, to keep them away from magnetic interference by the spacecraft and its electric circuits.[23]

- Electric sensors at the ends of opposing booms are used to measure potential differences between separated points, to derive electric fields associated with convection. The method works best at high plasma densities in low Earth orbit; far from Earth long booms are needed, to avoid shielding-out of electric forces.

- Radio sounders from the ground can bounce radio waves of varying frequency off the ionosphere, and by timing their return determine the electron density profile—up to its peak, past which radio waves no longer return. Radio sounders in low Earth orbit aboard the Canadian Alouette 1 (1962) and Alouette 2 (1965), beamed radio waves earthward and observed the electron density profile of the "topside ionosphere". Other radio sounding methods were also tried in the ionosphere (e.g. on IMAGE).

- Particle detectors include a Geiger counter, as was used for the original observations of the Van Allen radiation belt. Scintillator detectors came later, and still later "channeltron" electron multipliers found particularly wide use. To derive charge and mass composition, as well as energies, a variety of mass spectrograph designs were used. For energies up to about 50 keV (which constitute most of the magnetospheric plasma) time-of-flight spectrometers (e.g. "top-hat" design) are widely used.[citation needed]

Computers have made it possible to bring together decades of isolated

magnetic observations and extract average patterns of electrical

currents and average responses to interplanetary variations. They also

run simulations of the global magnetosphere and its responses, by

solving the equations of magnetohydrodynamics

(MHD) on a numerical grid. Appropriate extensions must be added to

cover the inner magnetosphere, where magnetic drifts and ionospheric

conduction need to be taken into account. So far the results are

difficult to interpret, and certain assumptions are needed to cover

small-scale phenomena.[citation needed]

Geomagnetic storm effects

Disruption of electrical systems

It has been suggested that a geomagnetic storm on the scale of the solar storm of 1859

today would cause billions or even trillions of dollars of damage to

satellites, power grids and radio communications, and could cause

electrical blackouts on a massive scale that might not be repaired for

weeks, months, or even years.[21] Such sudden electrical blackouts may threaten food production.[24]

Mains electricity grid

When magnetic fields move about in the vicinity of a conductor such as a wire, a geomagnetically induced current

is produced in the conductor. This happens on a grand scale during

geomagnetic storms (the same mechanism also influenced telephone and

telegraph lines before fiber optics, see above) on all long transmission

lines. Long transmission lines (many kilometers in length) are thus

subject to damage by this effect. Notably, this chiefly includes

operators in China, North America, and Australia, especially in modern

high-voltage, low-resistance lines. The European grid consists mainly of

shorter transmission circuits, which are less vulnerable to damage.[25][26]

The (nearly direct) currents induced in these lines from

geomagnetic storms are harmful to electrical transmission equipment,

especially transformers—inducing core saturation,

constraining their performance (as well as tripping various safety

devices), and causing coils and cores to heat up. In extreme cases, this

heat can disable or destroy them, even inducing a chain reaction that

can overload transformers.[27][28]

Most generators are connected to the grid via transformers, isolating

them from the induced currents on the grid, making them much less

susceptible to damage due to geomagnetically induced current.

However, a transformer that is subjected to this will act as an

unbalanced load to the generator, causing negative sequence current in

the stator and consequently rotor heating.

According to a study by Metatech corporation, a storm with a

strength comparable to that of 1921 would destroy more than 300

transformers and leave over 130 million people without power in the

United States, costing several trillion dollars.[29] The British Daily Mail even claimed that a massive solar flare could knock out electric power for months, but[30] these predictions are contradicted by a North American Electric Reliability Corporation

report that concludes that a geomagnetic storm would cause temporary

grid instability but no widespread destruction of high-voltage

transformers. The report points out that the widely quoted Quebec grid

collapse was not caused by overheating transformers but by the

near-simultaneous tripping of seven relays.[31]

Besides the transformers being vulnerable to the effects of a

geomagnetic storm, electricity companies can also be affected indirectly

by the geomagnetic storm. For instance, internet service providers may

go down during geomagnetic storms (and/or remain non-operational long

after). Electricity companies may have equipment requiring a working

internet connection to function, so during the period the internet

service provider is down, the electricity too may not be distributed.[32]

By receiving geomagnetic storm alerts and warnings (e.g. by the Space Weather Prediction Center;

via Space Weather satellites as SOHO or ACE), power companies can

minimize damage to power transmission equipment, by momentarily

disconnecting transformers or by inducing temporary blackouts.

Preventative measures also exist, including preventing the inflow of

GICs into the grid through the neutral-to-ground connection.[25]

Communications

High frequency

(3–30 MHz) communication systems use the ionosphere to reflect radio

signals over long distances. Ionospheric storms can affect radio

communication at all latitudes. Some frequencies are absorbed and others

are reflected, leading to rapidly fluctuating signals and unexpected propagation paths. TV and commercial radio stations are little affected by solar activity, but ground-to-air, ship-to-shore, shortwave broadcast and amateur radio

(mostly the bands below 30 MHz) are frequently disrupted. Radio

operators using HF bands rely upon solar and geomagnetic alerts to keep

their communication circuits up and running.

Military detection or early warning systems operating in the high frequency range are also affected by solar activity. The over-the-horizon radar

bounces signals off the ionosphere to monitor the launch of aircraft

and missiles from long distances. During geomagnetic storms, this system

can be severely hampered by radio clutter. Also some submarine

detection systems use the magnetic signatures of submarines as one input

to their locating schemes. Geomagnetic storms can mask and distort

these signals.

The Federal Aviation Administration

routinely receives alerts of solar radio bursts so that they can

recognize communication problems and avoid unnecessary maintenance. When

an aircraft and a ground station are aligned with the Sun, high levels

of noise can occur on air-control radio frequencies.[citation needed] This can also happen on UHF and SHF satellite communications, when an Earth station, a satellite and the Sun are in alignment.

In order to prevent unnecessary maintenance on satellite communications

systems aboard aircraft AirSatOne provides a live feed for geophysical

events from NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center. AirSatOne's live feed[33]

allows users to view observed and predicted space storms. Geophysical

Alerts are important to flight crews and maintenance personnel to

determine if any upcoming activity or history has or will have an effect

on satellite communications, GPS navigation and HF Communications.

Telegraph

lines in the past were affected by geomagnetic storms. Telegraphs used a

single long wire for the data line, stretching for many miles, using

the ground as the return wire and fed with DC

power from a battery; this made them (together with the power lines

mentioned below) susceptible to being influenced by the fluctuations

caused by the ring current.

The voltage/current induced by the geomagnetic storm could have

diminished the signal, when subtracted from the battery polarity, or to

overly strong and spurious signals when added to it; some operators

learned to disconnect the battery and rely on the induced current as

their power source. In extreme cases the induced current was so high the

coils at the receiving side burst in flames, or the operators received

electric shocks. Geomagnetic storms affect also long-haul telephone

lines, including undersea cables unless they are fiber optic.[34]

Damage to communications satellites can disrupt non-terrestrial telephone, television, radio and Internet links.[35] The National Academy of Sciences reported in 2008 on possible scenarios of widespread disruption in the 2012–2013 solar peak.[36]

The Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), and other navigation systems such as LORAN and the now-defunct OMEGA

are adversely affected when solar activity disrupts their signal

propagation. The OMEGA system consisted of eight transmitters located

throughout the world. Airplanes and ships used the very low frequency

signals from these transmitters to determine their positions. During

solar events and geomagnetic storms, the system gave navigators

information that was inaccurate by as much as several miles. If

navigators had been alerted that a proton event or geomagnetic storm was

in progress, they could have switched to a backup system.

GNSS signals are affected when solar activity causes sudden

variations in the density of the ionosphere, causing the satellite

signals to scintillate (like a twinkling star). The scintillation of satellite signals during ionospheric disturbances is studied at HAARP during ionospheric modification experiments. It has also been studied at the Jicamarca Radio Observatory.

One technology used to allow GPS receivers to continue to operate in the presence of some confusing signals is Receiver Autonomous Integrity Monitoring

(RAIM). However, RAIM is predicated on the assumption that a majority

of the GPS constellation is operating properly, and so it is much less

useful when the entire constellation is perturbed by global influences

such as geomagnetic storms. Even if RAIM detects a loss of integrity in

these cases, it may not be able to provide a useful, reliable signal.

Satellite hardware damage

Geomagnetic storms and increased solar ultraviolet emission heat Earth's upper atmosphere, causing it to expand. The heated air rises, and the density at the orbit of satellites up to about 1,000 km (621 mi) increases significantly. This results in increased drag, causing satellites to slow and change orbit slightly. Low Earth Orbit satellites that are not repeatedly boosted to higher orbits slowly fall and eventually burn up.

Skylab's 1979 destruction is an example of a spacecraft reentering

Earth's atmosphere prematurely as a result of higher-than-expected

solar activity. During the great geomagnetic storm of March 1989, four

of the Navy's navigational satellites had to be taken out of service for

up to a week, the U.S. Space Command had to post new orbital elements for over 1000 objects affected and the Solar Maximum Mission satellite fell out of orbit in December the same year.[citation needed]

The vulnerability of the satellites depends on their position as well. The South Atlantic Anomaly is a perilous place for a satellite to pass through.

As technology has allowed spacecraft components to become

smaller, their miniaturized systems have become increasingly vulnerable

to the more energetic solar particles. These particles can physically damage microchips and can change software commands in satellite-borne computers.[citation needed]

Another problem for satellite operators is differential charging. During geomagnetic storms, the number and energy of electrons and ions increase. When a satellite travels through this energized environment, the charged particles striking the spacecraft differentially charge portions of the spacecraft. Discharges can arc across spacecraft components, harming and possibly disabling them.[citation needed]

Bulk charging (also called deep charging) occurs when energetic

particles, primarily electrons, penetrate the outer covering of a

satellite and deposit their charge in its internal parts. If sufficient

charge accumulates in any one component, it may attempt to neutralize by

discharging to other components. This discharge is potentially

hazardous to the satellite's electronic systems.[citation needed]

Geologic exploration

Earth's

magnetic field is used by geologists to determine subterranean rock

structures. For the most part, these geodetic surveyors are searching

for oil, gas or mineral deposits. They can accomplish this only when

Earth's field is quiet, so that true magnetic signatures can be

detected. Other geophysicists prefer to work during geomagnetic storms,

when strong variations in the Earth's normal subsurface electric

currents allow them to sense subsurface oil or mineral structures. This

technique is called magnetotellurics. For these reasons, many surveyors use geomagnetic alerts and predictions to schedule their mapping activities.[citation needed]

Pipelines

Rapidly fluctuating geomagnetic fields can produce geomagnetically induced currents in pipelines. This can cause multiple problems for pipeline engineers. Pipeline flow meters can transmit erroneous flow information and the corrosion rate of the pipeline can be dramatically increased.[37][38]

Radiation hazards to humans

Intense solar flares release very-high-energy particles that can cause radiation poisoning.[citation needed]

Earth's atmosphere and magnetosphere allow adequate protection at ground level, but astronauts are subject to potentially lethal doses of radiation. The penetration of high-energy particles into living cells can cause chromosome damage, cancer and other health problems. Large doses can be immediately fatal.

Solar proton events can also produce elevated radiation aboard aircraft

flying at high altitudes. Although these risks are small, monitoring of

solar proton events by satellite instrumentation allows the occasional

exposure to be monitored and evaluated and eventually flight paths and

altitudes adjusted in order to lower the absorbed dose of the flight crews.[40][41][42]

Effect on animals

Scientists are still studying whether or not animals are affected by this, some suggesting this is why whales beach themselves.[43][44]

Some have stated the possibility that other migrating animals including

birds and honey bees, might be affected since they also use magnetoreception to navigate, and geomagnetic storms alter the Earth's magnetic fields temporarily.[45]