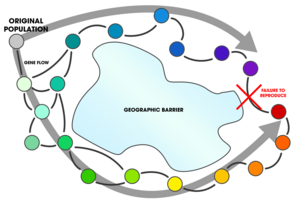

In

a ring species, gene flow occurs between neighbouring populations of a

species, but at the ends of the "ring" , the populations cannot

interbreed.

The coloured bars show natural populations (colours), varying along a cline. Such variation may occur in a line (e.g. up a mountain slope) as in A, or may wrap around as in B.

Where the cline bends around, populations next to each other on the

cline can interbreed, but at the point that the beginning meets the end

again, as at C, the differences along the cline prevent interbreeding (gap between pink and green). The interbreeding populations are then called a ring species.

In biology, a ring species

is a connected series of neighbouring populations, each of which can

interbreed with closely sited related populations, but for which there

exist at least two "end" populations in the series, which are too

distantly related to interbreed, though there is a potential gene flow between each "linked" population. Such non-breeding, though genetically connected, "end" populations may co-exist in the same region (sympatry) thus closing a "ring". The German term Rassenkreis, meaning a ring of populations, is also used.

Ring species represent speciation and have been cited as evidence of evolution.

They illustrate what happens over time as populations genetically

diverge, specifically because they represent, in living populations,

what normally happens over time between long-deceased ancestor

populations and living populations, in which the intermediates have

become extinct. The evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins

remarks that ring species "are only showing us in the spatial dimension

something that must always happen in the time dimension".

Formally, the issue is that interfertility (ability to interbreed) is not a transitive relation; if A can breed with B, and B can breed with C, it does not mean that A can breed with C, and therefore does not define an equivalence relation. A ring species is a species with a counterexample to the transitivity of interbreeding.

However, it is unclear whether any of the examples of ring species

cited by scientists actually permit gene flow from end to end, with many

being debated and contested.

History

- The Larus gulls interbreed in a ring around the arctic. 1: L. fuscus, 2: Siberian population of L. fuscus, 3: L. heuglini, 4: L. vegae birulai, 5: L. vegae, 6: L. smithsonianus, 7: L. argentatus

- Herring gull (Larus argentatus) (front) and lesser black-backed gull (Larus fuscus) (behind) in Norway: two phenotypes with clear differences

The classic ring species is the Larus gull. In 1925 Jonathan Dwight

found the genus to form a chain of varieties around the Arctic Circle.

However, doubts have arisen as to whether this represents an actual ring

species. In 1938, Claud Buchanan Ticehurst argued that the greenish warbler

had spread from Nepal around the Tibetan Plateau, while adapting to

each new environment, meeting again in Siberia where the ends no longer

interbreed. These and other discoveries led Mayr to first formulate a theory on ring species in his 1942 study Systematics and the Origin of Species. Also in the 1940s, Robert C. Stebbins described the Ensatina salamanders around the Californian Central Valley as a ring species; but again, some authors such as Jerry Coyne consider this classification incorrect. Finally in 2012, the first example of a ring species in plants was found in a spurge, forming a ring around the Caribbean Sea.

Speciation

The biologist Ernst Mayr championed the concept of ring species, claiming that it unequivocally demonstrated the process of speciation. A ring species is an alternative model to allopatric speciation,

"illustrating how new species can arise through 'circular overlap',

without interruption of gene flow through intervening populations…" However, Jerry Coyne and H. Allen Orr point out that rings species more closely model parapatric speciation.

Ring species often attract the interests of evolutionary

biologists, systematists, and researchers of speciation leading to both

thought provoking ideas and confusion concerning their definition.

Contemporary scholars recognize that examples in nature have proved

rare due to various factors such as limitations in taxonomic delineation or, "taxonomic zeal"—explained by the fact that taxonomists classify organisms into "species", while ring species often cannot fit this definition.

Other reasons such as gene flow interruption from "vicariate

divergence" and fragmented populations due to climate instability have

also been cited.

Ring species also present an interesting case of the species problem for those seeking to divide the living world into discrete species.

All that distinguishes a ring species from two separate species is the

existence of the connecting populations; if enough of the connecting

populations within the ring perish to sever the breeding connection then

the ring species' distal populations will be recognized as two distinct

species. The problem is whether to quantify the whole ring as a single

species (despite the fact that not all individuals can interbreed) or to

classify each population as a distinct species (despite the fact that

it can interbreed with its near neighbours). Ring species illustrate

that species boundaries arise gradually and often exist on a continuum.

Examples

Ensatina salamanders example of ring species

Speculated evolution and spread of the greenish warbler.

P. t. trochiloides

P. t. obscuratus

P. t. plumbeitarsus

P. t. "ludlowi"

P. t. viridanus

Note: The P. t. nitidus in the Caucasus Mountains is not shown

Many examples have been documented in nature. Debate exists

concerning much of the research, with some authors citing evidence

against their existence entirely.

The following examples provide evidence that—despite the limited number

of concrete, idealized examples in nature—continuums of species do

exist and can be found in biological systems. This is often characterized by sub-species level classifications such as clines, ecotypes, complexes, and varieties.

Many examples have been disputed by researchers, and equally "many of

the [proposed] cases have received very little attention from

researchers, making it difficult to assess whether they display the

characteristics of ideal ring species."

The following list gives examples of ring species found in nature. Some of the examples such as the Larus gull complex, the greenish warbler of Asia, and the Ensatina salamanders of America, have been disputed.

- Acanthiza pusilla and A. ewingii

- Acacia karroo

- Alauda skylarks (Alauda arvensis, A. japonica and A. gulgula)

- Alophoixus

- Aulostomus (Trumpetfish)

- Camarhynchus psittacula and C. pauper

- Chaerephon pumilus species complex

- Ensatina salamanders

- Euphorbia tithymaloides is a group within the spurge family that has reproduced and evolved in a ring through Central America and the Caribbean, meeting in the Virgin Islands where they appear to be morphologically and ecologically distinct.

- Great tit (however, some studies dispute this example)

- The greenish warbler (Phylloscopus trochiloides) forms a species ring, around the Himalayas. It is thought to have spread from Nepal around the inhospitable Tibetan Plateau, to rejoin in Siberia, where the plumbeitarsus and the viridanus appeared to no longer mutually reproduce.

- Hoplitis producta

- House mouse

- Junonia coenia and J. genoveva/J. evarete

- Lalage leucopygialis, L. nigra, and L. sueurii

- Larus gulls form a circumpolar "ring" around the North Pole. The European herring gull (L. argentatus argenteus), which lives primarily in Great Britain and Ireland, can hybridize with the American herring gull (L. smithsonianus), (living in North America), which can also hybridize with the Vega or East Siberian herring gull (L. vegae), the western subspecies of which, Birula's gull (L. vegae birulai), can hybridize with Heuglin's gull (L. heuglini), which in turn can hybridize with the Siberian lesser black-backed gull (L. fuscus). All four of these live across the north of Siberia. The last is the eastern representative of the lesser black-backed gulls back in north-western Europe, including Great Britain. The lesser black-backed gulls and herring gulls are sufficiently different that they do not normally hybridize; thus the group of gulls forms a continuum except where the two lineages meet in Europe. However, a 2004 genetic study entitled "The herring gull complex is not a ring species" has shown that this example is far more complicated than presented here (Liebers et al., 2004): this example only speaks to the complex of species from the classical herring gull through lesser black-backed gull. There are several other taxonomically unclear examples that belong in the same species complex, such as yellow-legged gull (L. michahellis), glaucous gull (L. hyperboreus), and Caspian gull (L. cachinnans).

- Pelophylax nigromaculatus and P. porosus/P. porosus brevipodus (the names and classification of these species have changed since the publication suggesting a ring species)

- Pernis ptilorhynchus and P. celebensis

- Perognathus amplus and P. longimembris

- Peromyscus maniculatus

- Phellinus

- Platycercus elegans (Crimson rosella) complex

- Drosophila paulistorum

- Phylloscopus collybita and P. sindianus

- Phylloscopus (Willow warblers)

- Powelliphanta

- Rhymogona silvatica and R. cervina (the names and classification of these species have changed since the publication suggesting a ring species)

- Melospiza melodia, a song sparrow, forms a ring around the Sierra Nevada of California with the subspecies heermanni and fallax meeting in the vicinity of the San Gorgonio Pass.

- Todiramphus chloris and T. cinnamominus