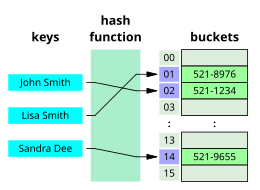

Visual representation of a hash table, a data structure that allows for fast retrieval of information.

In computer science, a search algorithm is any algorithm which solves the search problem, namely, to retrieve information stored within some data structure, or calculated in the search space of a problem domain, either with discrete or continuous values. Specific applications of search algorithms include:

- Problems in combinatorial optimization, such as:

- The vehicle routing problem, a form of shortest path problem

- The knapsack problem: Given a set of items, each with a weight and a value, determine the number of each item to include in a collection so that the total weight is less than or equal to a given limit and the total value is as large as possible.

- The nurse scheduling problem

- Problems in constraint satisfaction, such as:

- The map coloring problem

- Filling in a sudoku or crossword puzzle

- In game theory and especially combinatorial game theory, choosing the best move to make next (such as with the minmax algorithm)

- Finding a combination or password from the whole set of possibilities

- Factoring an integer (an important problem in cryptography)

- Optimizing an industrial process, such as a chemical reaction, by changing the parameters of the process (like temperature, pressure, and pH)

- Retrieving a record from a database

- Finding the maximum or minimum value in a list or array

- Checking to see if a given value is present in a set of values

The classic search problems described above and web search are both problems in information retrieval,

but are generally studied as separate subfields and are solved and

evaluated differently.

are generally focused on filtering and

that find documents most relevant to human queries. Classic search

algorithms are typically evaluated on how fast they can find a solution,

and whether that solution is guaranteed to be optimal. Though

information retrieval algorithms must be fast, the quality of ranking is

more important, as is whether good results have been left out and bad

results included.

The appropriate search algorithm often depends on the data

structure being searched, and may also include prior knowledge about the

data. Some database structures are specially constructed to make search

algorithms faster or more efficient, such as a search tree, hash map, or a database index.

Search algorithms can be classified based on their mechanism of searching. Linear search algorithms check every record for the one associated with a target key in a linear fashion. Binary, or half interval searches,

repeatedly target the center of the search structure and divide the

search space in half. Comparison search algorithms improve on linear

searching by successively eliminating records based on comparisons of

the keys until the target record is found, and can be applied on data

structures with a defined order. Digital search algorithms work based on the properties of digits in data structures that use numerical keys. Finally, hashing directly maps keys to records based on a hash function. Searches outside a linear search require that the data be sorted in some way.

Algorithms are often evaluated by their computational complexity, or maximum theoretical run time. Binary search functions, for example, have a maximum complexity of O(log n),

or logarithmic time. This means that the maximum number of operations

needed to find the search target is a logarithmic function of the size

of the search space.

Classes

For virtual search spaces

Algorithms for searching virtual spaces are used in the constraint satisfaction problem, where the goal is to find a set of value assignments to certain variables that will satisfy specific mathematical equations and inequations / equalities. They are also used when the goal is to find a variable assignment that will maximize or minimize a certain function of those variables. Algorithms for these problems include the basic brute-force search (also called "naïve" or "uninformed" search), and a variety of heuristics that try to exploit partial knowledge about the structure of this space, such as linear relaxation, constraint generation, and constraint propagation.

An important subclass are the local search methods, that view the elements of the search space as the vertices

of a graph, with edges defined by a set of heuristics applicable to the

case; and scan the space by moving from item to item along the edges,

for example according to the steepest descent or best-first criterion, or in a stochastic search. This category includes a great variety of general metaheuristic methods, such as simulated annealing, tabu search, A-teams, and genetic programming, that combine arbitrary heuristics in specific ways.

This class also includes various tree search algorithms, that view the elements as vertices of a tree, and traverse that tree in some special order. Examples of the latter include the exhaustive methods such as depth-first search and breadth-first search, as well as various heuristic-based search tree pruning methods such as backtracking and branch and bound.

Unlike general metaheuristics, which at best work only in a

probabilistic sense, many of these tree-search methods are guaranteed to

find the exact or optimal solution, if given enough time. This is

called "completeness".

Another important sub-class consists of algorithms for exploring the game tree of multiple-player games, such as chess or backgammon,

whose nodes consist of all possible game situations that could result

from the current situation. The goal in these problems is to find the

move that provides the best chance of a win, taking into account all

possible moves of the opponent(s). Similar problems occur when humans

or machines have to make successive decisions whose outcomes are not

entirely under one's control, such as in robot guidance or in marketing, financial, or military strategy planning. This kind of problem — combinatorial search — has been extensively studied in the context of artificial intelligence. Examples of algorithms for this class are the minimax algorithm, alpha–beta pruning, * Informational search and the A* algorithm.

For sub-structures of a given structure

The name "combinatorial search" is generally used for algorithms that look for a specific sub-structure of a given discrete structure, such as a graph, a string, a finite group, and so on. The term combinatorial optimization

is typically used when the goal is to find a sub-structure with a

maximum (or minimum) value of some parameter. (Since the sub-structure

is usually represented in the computer by a set of integer variables

with constraints, these problems can be viewed as special cases of

constraint satisfaction or discrete optimization; but they are usually

formulated and solved in a more abstract setting where the internal

representation is not explicitly mentioned.)

An important and extensively studied subclass are the graph algorithms, in particular graph traversal algorithms, for finding specific sub-structures in a given graph — such as subgraphs, paths, circuits, and so on. Examples include Dijkstra's algorithm, Kruskal's algorithm, the nearest neighbour algorithm, and Prim's algorithm.

Another important subclass of this category are the string searching algorithms, that search for patterns within strings. Two famous examples are the Boyer–Moore and Knuth–Morris–Pratt algorithms, and several algorithms based on the suffix tree data structure.

Search for the maximum of a function

In 1953, American statistician Jack Kiefer devised Fibonacci search which can be used to find the maximum of a unimodal function and has many other applications in computer science.

For quantum computers

There are also search methods designed for quantum computers, like Grover's algorithm, that are theoretically faster than linear or brute-force search even without the help of data structures or heuristics.