An Amish family riding in a traditional Amish buggy in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 342,000 (2019, Old Order Amish) | |

| Founder | |

| Jakob Ammann | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (notably Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin, and New York) Canada (Ontario, and Prince Edward Island) | |

| Religions | |

| Anabaptist | |

| Scriptures | |

| The Bible | |

| Languages | |

| Pennsylvania German, Bernese German, Low Alemannic Alsatian German, Amish High German, English |

The Amish (/ˈɑːmɪʃ/; Pennsylvania German: Amisch; German: Amische) are a group of traditionalist Christian church fellowships with Swiss German Anabaptist origins. They are closely related to, but distinct from, Mennonite churches. The Amish are known for simple living, plain dress, and reluctance to adopt many conveniences of modern technology.

The history of the Amish church began with a schism in Switzerland within a group of Swiss and Alsatian Anabaptists in 1693 led by Jakob Ammann. Those who followed Ammann became known as Amish. In the second half of the 19th century, the Amish divided into Old Order Amish and Amish Mennonites. The latter do not eschew motor cars, whereas the Old Order Amish retained much of their traditional culture. When people refer to the Amish today, they normally refer to the Old Order Amish.

In the early 18th century, many Amish and Mennonites immigrated to Pennsylvania for a variety of reasons. Today, the Old Order Amish, the New Order Amish, and the Old Beachy Amish continue to speak Pennsylvania German, also known as "Pennsylvania Dutch", although two different Alemannic dialects are used by Old Order Amish in Adams and Allen counties in Indiana.

As of 2000, over 165,000 Old Order Amish lived in the United States and about 1,500 lived in Canada. A 2008 study suggested their numbers had increased to 227,000, and in 2010, a study suggested their population had grown by 10 percent in the past two years to 249,000, with increasing movement to the West. Most of the Amish continue to have six or seven children, while benefiting from the major decrease in infant and maternal mortality in the 20th century. Between 1992 and 2017, the Amish population increased by 149 percent, while the U.S. population increased by 23 percent.

Amish church membership begins with baptism, usually between the ages of 16 and 23. It is a requirement for marriage within the Amish church. Once a person is baptized within the church, he or she may marry only within the faith. Church districts have between 20 and 40 families and worship services are held every other Sunday in a member's home. The district is led by a bishop and several ministers and deacons. The rules of the church, the Ordnung, must be observed by every member and cover many aspects of day-to-day living, including prohibitions or limitations on the use of power-line electricity, telephones, and automobiles, as well as regulations on clothing. Most Amish do not buy commercial insurance or participate in Social Security. As present-day Anabaptists, Amish church members practice nonresistance and will not perform any type of military service. The Amish value rural life, manual labor, and humility, all under the auspices of living what they interpret to be God's word.

Members who do not conform to these community expectations and who cannot be convinced to repent are excommunicated. In addition to excommunication, members may be shunned, a practice that limits social contacts to shame the wayward member into returning to the church. Almost 90 percent of Amish teenagers choose to be baptized and join the church. During an adolescent period of rumspringa ("running around") in some communities, nonconforming behavior that would result in the shunning of an adult who had made the permanent commitment of baptism, may be met with a degree of forbearance. Amish church groups seek to maintain a degree of separation from the non-Amish world, i.e. American and Canadian society. Non-Amish people are generally referred to as "English". Generally, a heavy emphasis is placed on church and family relationships. The Amish typically operate their own one-room schools and discontinue formal education after grade eight, at age 13 or 14. Until the children turn 16, they have vocational training under the tutelage of their parents, community, and the school teacher. Higher education is generally discouraged, as it can lead to social segregation and the unraveling of the community. However, some Amish women have used higher education to obtain a nursing certificate so that they may provide midwifery services to the community.

History

Anabaptist beginnings

Cover of The Amish and the Mennonites, 1938

An old Amish cemetery in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1941

The Anabaptist movement, from which the Amish later emerged, started in circles around Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531) who led the early Reformation in Switzerland. In Zürich on January 21, 1525, Conrad Grebel and George Blaurock practiced adult baptism to each other and then to others. This Swiss movement, part of the Radical Reformation, later became known as Swiss Brethren.

Emergence of the Amish

The term Amish was first used as a Schandename (a term of disgrace) in 1710 by opponents of Jakob Amman. The first informal division between Swiss Brethren was recorded in the 17th century between Oberländers (those living in the hills) and Emmentaler (those living in the Emmental valley). The Oberländers were a more extreme congregation; their zeal pushed them into more remote areas and their solitude made them more zealous.

Swiss Anabaptism developed, from this point, in two parallel

streams, most clearly marked by disagreement over the preferred

treatment of "fallen" believers. The Emmentalers (sometimes referred to

as Reistians, after bishop Hans Reist, a leader among the Emmentalers) argued that fallen believers should only be withheld from communion,

and not regular meals. The Amish argued that those who had been banned

should be avoided even in common meals. The Reistian side eventually

formed the basis of the Swiss Mennonite Conference.

Because of this common heritage, Amish and Mennonites from southern

Germany and Switzerland retain many similarities. Those who leave the

Amish fold tend to join various congregations of Conservative Mennonites.

Migration to North America

Amish began migrating to Pennsylvania, then known for its religious toleration, in 1727 as part of a larger migration from the Palatinate and neighboring areas. This migration was a reaction to religious wars, poverty, and religious persecution in Europe. The first Amish immigrants went to the region that became Berks County, Pennsylvania, but later moved, motivated by land issues and by security concerns tied to the French and Indian War. Many eventually settled in Lancaster County. Other groups later settled elsewhere in North America.

1850–1878 Division into Old Orders and Amish Mennonites

Most Amish communities that were established in North America did not

ultimately retain their Amish identity. The major division that

resulted in the loss of identity of many Amish congregations occurred in

the third quarter of the 19th century. The forming of factions worked

its way out at different times at different places. The process was

rather a "sorting out" than a split. Amish people are free to join

another Amish congregation at another place that fits them best.

In the years after 1850, tensions rose within individual Amish

congregations and between different Amish congregations. Between 1862

and 1878, yearly Dienerversammlungen

(ministerial conferences) were held at different places, concerning how

the Amish should deal with the tensions caused by the pressures of

modern society.

The meetings themselves were a progressive idea; for bishops to

assemble to discuss uniformity was an unprecedented notion in the Amish

church. By the first several meetings, the more traditionally minded bishops agreed to boycott the conferences.

The more progressive members, comprising roughly two-thirds of

the group, became known by the name Amish Mennonite, and eventually

united with the Mennonite Church,

and other Mennonite denominations, mostly in the early 20th century.

The more traditionally minded groups became known as the Old Order

Amish. The Egli Amish

had already started to withdraw from the Amish church in 1858. They

soon drifted away from the old ways and changed their name to

"Defenseless Mennonite" in 1908. Congregations who took no side in the division after 1862 formed the Conservative Amish Mennonite Conference in 1910, but dropped the word "Amish" from their name in 1957.

Because no division occurred in Europe, the Amish congregations

remaining there took the same way as the change-minded Amish Mennonites

in North America and slowly merged with the Mennonites. The last Amish congregation in Germany to merge was the Ixheim

Amish congregation, which merged with the neighboring Mennonite Church

in 1937. Some Mennonite congregations, including most in Alsace, are descended directly from former Amish congregations.

20th century

Though

splits happened among the Old Order in the 19th century in Mifflin

County, Pennsylvania, a major split among the Old Orders took until World War I. At that time, two very conservative affiliations emerged – the Swartzentruber Amish in Holmes County, Ohio, and the Buchanan Amish in Iowa. The Buchanan Amish soon were joined by like-minded congregations all over the country.

With World War I came the massive suppression of the German language in the US that eventually led to language shift of most Pennsylvania German speakers, leaving the Amish and other Old Orders as almost the only speakers by the end of the 20th century. This created a language barrier around the Amish that did not exist before in that form.

In the late 1920s, the more change minded faction of the Old

Order Amish, that wanted to adopt the car, broke away from the

mainstream and organized under the name Beachy Amish.

During the Second World War, the old question of military service for the Amish came up again. Because Amish young men in general refused military service, they ended up in the Civilian Public Service

(CPS), where they worked mainly in forestry and hospitals. The fact

that many young men worked in hospitals, where they had a lot of contact

with more progressive Mennonites and the outside world, had the result

that many of these men never joined the Amish church.

In the 1950s, the Beachy Amish transformed into an evangelical

church. The ones who wanted to preserve the old way of the Beachy became

the Old Beachy Amish.

Until about 1950, almost all Amish children attended small,

local, non-Amish schools, but then school consolidation and mandatory

schooling beyond eighth grade caused Amish opposition. Amish communities

opened their own Amish schools. In 1972, the United States Supreme Court exempted Amish pupils from compulsory education past eighth grade. By the end of the 20th century, almost all Amish children attended Amish schools.

In the last quarter of the 20th century, a growing number of

Amish men left farm work and started small businesses because of

increasing pressure on small-scale farming. Though a wide variety of

small businesses exists among the Amish, construction work and

woodworking are quite widespread. In many Amish settlements, especially the larger ones, farmers are now a minority. Approximately 12,000 of the 40,000 dairy farms in the United States are Amish-owned as of 2018.

Until the early 20th century, Old Order Amish identity was not

linked to the use of technologies, as the Old Order Amish and their

rural neighbors used the same farm and household technologies. Questions

about the use of technologies also did not play a role in the Old Order

division of the second half of the 19th century. Telephones were the

first important technology that was rejected, soon followed by the

rejection of cars, tractors, radios, and many other technological

inventions of the 20th century.

Religious practices

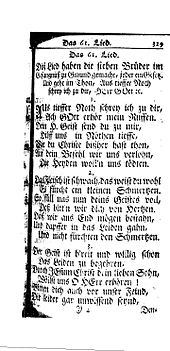

A scan of the historical document Diß Lied haben die sieben Brüder im Gefängnüß zu Gmünd gemacht

Two key concepts for understanding Amish practices are their rejection of Hochmut (pride, arrogance, haughtiness) and the high value they place on Demut (humility) and Gelassenheit (calmness, composure, placidity), often translated as "submission" or "letting-be". Gelassenheit

is perhaps better understood as a reluctance to be forward, to be

self-promoting, or to assert oneself. The Amish's willingness to submit

to the "Will of Jesus",

expressed through group norms, is at odds with the individualism so

central to the wider American culture. The Amish anti-individualist

orientation is the motive for rejecting labor-saving technologies that

might make one less dependent on the community. Modern innovations such

as electricity might spark a competition for status goods, or

photographs might cultivate personal vanity. Electric power lines would

be going against the Bible, which says that you shall not be "conformed

to the world" (Romans 12:2).

Way of life

Amish couple in horse-driven buggy in rural Holmes County, Ohio, September 2004

Amish lifestyle is regulated by the Ordnung ('order'),

which differs slightly from community to community, and within a

community, from district to district. What is acceptable in one

community may not be acceptable in another. The Ordnung

is agreed upon – or changed – within the whole community of baptized

members prior to Communion which takes place two times a year. The

meeting where the Ordnung is discussed is called Ordnungsgemeine in Standard German and Ordningsgmee in Pennsylvania Dutch. The Ordnung

include matters such as dress, permissible uses of technology,

religious duties, and rules regarding interaction with outsiders. In

these meetings, women also vote in questions concerning the Ordnung.

Bearing children, raising them, and socializing with neighbors

and relatives are the greatest functions of the Amish family. Amish

typically believe that large families are a blessing from God. Farm

families tend to have larger families, because sons are needed to

perform farm labor. Community is central to the Amish way of life.

Working hard is considered godly, and some technological

advancements have been considered undesirable because they reduce the

need for hard work. Machines such as automatic floor cleaners in barns

have historically been rejected as this provides young farmhands with

too much free time.

Clothing

The

Amish are known for their plain attire. Men wear solid colored shirts,

broad-brimmed hats, and suits that signify similarity amongst one

another. Amish men grow beards to symbolize manhood and marital status,

as well as to promote humility. They are forbidden to grow mustaches

because mustaches are seen by the Amish as being affiliated with the

military, which they are strongly opposed to, due to their pacifist

beliefs. Women have similar guidelines on how to dress, which are also

expressed in the Ordnung,

the Amish version of legislation. They are to wear calf-length dresses,

muted colors along with bonnets and aprons. Prayer caps or bonnets are

worn by the women because they are a visual representation of their

religious beliefs and promote unity through the tradition of every women

wearing one. The color of the bonnet signifies whether a woman is

single or married. Single women wear black bonnets and married women

wear white. The color coding of bonnets is important because women are

not allowed to wear jewelry, such as wedding rings, as it is seen as

drawing attention to the body which can induce pride in the individual.

All clothing is sewn by hand, but the way to fasten the garment widely

depends on whether the Amish person is a part of the New Order or Old

Order Amish. The Old Order Amish seldom, if ever, use buttons because they are seen as too flashy; instead, they use the hook and eye

approach to fashion clothing or metal snaps. The New Order Amish are

slightly more progressive and allow the usage of buttons to help attire

clothing.

Cuisine

Amish cuisine is noted for its simplicity and traditional qualities.

Food plays an important part in Amish social life and is served at potlucks, weddings, fundraisers, farewells, and other events.

Many Amish foods are sold at markets including pies, preserves, bread

mixes, pickled produce, desserts, and canned goods. Many Amish

communities have also established restaurants for visitors. Amish meat

consumption is similar to the American average though they tend to eat

more preserved meat.

Subgroups of Amish

Over the years, the Amish churches have divided many times mostly

over questions concerning the Ordnung, but also over doctrinal disputes,

mainly about shunning. The largest group, the "Old Order" Amish, a

conservative faction that separated from other Amish in the 1860s, are

those who have most emphasized traditional practices and beliefs. The New Order Amish are a group of Amish whom some scholars see best described as a subgroup of Old Order Amish, despite the name.

Affiliations

About

40 different Old Order Amish affiliations are known; the eight major

affiliations are below, with Lancaster as the largest one in number of

districts and population:

| Affiliation | Date established | Origin | States | Settlements | Church districts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lancaster | 1760 | Pennsylvania | 8 | 37 | 291 |

| Elkhart-LaGrange | 1841 | Indiana | 3 | 9 | 176 |

| Holmes Old Order | 1808 | Ohio | 1 | 2 | 147 |

| Buchanan/Medford | 1914 | Indiana | 19 | 67 | 140 |

| Geauga I | 1886 | Ohio | 6 | 11 | 113 |

| Swartzentruber | 1913 | Ohio | 15 | 43 | 119 |

| Geauga II | 1962 | Ohio | 4 | 27 | 99 |

| Swiss (Adams) | 1850 | Indiana | 5 | 15 | 86 |

Use of technology by different Amish affiliations

The

table below indicates the use of certain technologies by different

Amish affiliations. The use of cars is not allowed by any Old and New

Order Amish, nor are radio, television, or in most cases the use of the

Internet. The three affiliations: "Lancaster", "Holmes Old Order", and

"Elkhart-LaGrange" are not only the three largest affiliations, but they

also represent the mainstream among the Old Order Amish. The most

conservative affiliations are above, the most modern ones below.

Technologies used by very few are on the left; the ones used by most are

on the right. The percentage of all Amish who use a technology is also

indicated approximately.

The Old Order Amish culture involves lower greenhouse gas emissions in

all sectors and activities with the exception of diet, and their

per-person emissions has been estimated to be less than one quarter that

of the wider society.

Language

Most Old Order Amish speak Pennsylvania Dutch, and refer to non-Amish people as "English", regardless of ethnicity. Some Amish who migrated to the United States in the 1850s speak a form of Bernese German or a Low Alemannic Alsatian dialect.

Contrary to popular belief, the word "Dutch" in "Pennsylvania

Dutch" is not a mistranslation, but rather a corruption of the

Pennsylvania German endonym Deitsch, which means "Pennsylvania Dutch / German" or "German". Ultimately, the terms Deitsch, Dutch, Diets and Deutsch are all cognates of the Proto-Germanic word *þiudiskaz meaning "popular" or "of the people". The continued use of "Pennsylvania Dutch" was strengthened by the Pennsylvania Dutch in the 19th century as a way of distinguishing themselves from later (post 1830) waves of German immigrants to the United States, with the Pennsylvania Dutch referring to themselves as Deitsche and to Germans as Deitschlenner (literally "Germany-ers", compare Deutschland-er) whom they saw as a related but distinct group.

According to one scholar, "today, almost all Amish are

functionally bilingual in Pennsylvania Dutch and English; however,

domains of usage are sharply separated. Pennsylvania Dutch dominates in

most in-group settings, such as the dinner table and preaching in church

services. In contrast, English is used for most reading and writing.

English is also the medium of instruction in schools and is used in

business transactions and often, out of politeness, in situations

involving interactions with non-Amish. Finally, the Amish read prayers

and sing in Standard German (which, in Pennsylvania Dutch, is called Hochdeitsch) at church services. The distinctive use of three different languages serves as a powerful conveyor of Amish identity.

"Although 'the English language is being used in more and more

situations,' Pennsylvania Dutch is 'one of a handful of minority

languages in the United States that is neither endangered nor supported

by continual arrivals of immigrants.'"

Ethnicity

The Amish largely share a German or Swiss-German ancestry. They generally use the term "Amish" only for members of their faith community and not as an ethnic designation. However some Amish descendants

recognize their cultural background knowing that their genetic and

cultural traits are uniquely different from other ethnicities.

Those who choose to affiliate with the church, or young children raised

in Amish homes, but too young to yet be church members, are considered

to be Amish. Certain Mennonite churches have a high number of people who

were formerly from Amish congregations. Although more Amish immigrated

to North America in the 19th century than during the 18th century, most

of today's Amish descend from 18th-century immigrants. The latter tended

to emphasize tradition to a greater extent, and were perhaps more

likely to maintain a separate Amish identity.

There are a number of Amish Mennonite church groups that had never in

their history been associated with the Old Order Amish because they

split from the Amish mainstream in the time when the Old Orders formed

in the 1860s and 1870s. The former Western Ontario Mennonite Conference

(WOMC) was made up almost entirely of former Amish Mennonites who

reunited with the Mennonite Church in Canada. Orland Gingerich's book The Amish of Canada devotes the vast majority of its pages not to the Beachy or Old Order Amish, but to congregations in the former WOMC.

Para-Amish groups

Several other groups, called "para-Amish" by G. C. Waldrep and others, share many characteristics with the Amish, such as horse and buggy transportation, plain dress, and the preservation of the German language.

The members of these groups are largely of Amish origin, but they are

not in fellowship with other Amish groups because they adhere to

theological doctrines (e.g., assurance of salvation) or practices (community of goods) that are normally not accepted among mainstream Amish. The Bergholz Community is a different case, it is not seen as Amish anymore because the community has shifted away from many core Amish principles.

Population

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1920 | 5,000 | — |

| 1928 | 7,000 | +4.30% |

| 1936 | 9,000 | +3.19% |

| 1944 | 13,000 | +4.70% |

| 1952 | 19,000 | +4.86% |

| 1960 | 28,000 | +4.97% |

| 1968 | 39,000 | +4.23% |

| 1976 | 57,000 | +4.86% |

| 1984 | 84,000 | +4.97% |

| 1992 | 128,150 | +5.42% |

| 2000 | 166,000 | +3.29% |

| 2010 | 249,500 | +4.16% |

| 2019 | 341,900 | +3.56% |

| Source: 1992, 2000, 2010, 2019 | ||

Because the Amish are usually baptized no earlier than 18 and

children are not counted in local congregation numbers, estimating their

numbers is difficult. Rough estimates from various studies placed their

numbers at 125,000 in 1992, 166,000 in 2000, and 221,000 in 2008.

Thus, from 1992 to 2008, population growth among the Amish in North

America was 84 percent (3.6 percent per year). During that time, they

established 184 new settlements and moved into six new states. In 2000, about 165,620 Old Order Amish resided in the United States, of whom 73,609 were church members. The Amish are among the fastest-growing populations in the world, with an average of seven children per family in the 1970s and a total fertility rate of 5.3 in the 2010s.

In 2010, a few religious bodies, including the Amish, changed the

way their adherents were reported to better match the standards of the

Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies. When looking

at all Amish adherents and not solely Old Order Amish, about 241,000

Amish adherents were in 28 U.S. states in 2010.

Distribution

United States

| U.S. state | Amish pop. in 1992 | Amish pop. in 2000 | Amish pop. in 2010 | Amish pop. in 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pennsylvania | 32,710 | 40,100 | 59,350 | 79,200 |

| Ohio | 34,830 | 49,750 | 58,590 | 76,195 |

| Indiana | 23,400 | 32,650 | 43,710 | 57,430 |

| Wisconsin | 6,785 | 10,250 | 15,360 | 22,020 |

| New York | 4,050 | 5,000 | 12,015 | 20,595 |

| Michigan | 5,150 | 9,300 | 11,350 | 16,410 |

| Missouri | 3,745 | 6,100 | 9,475 | 13,990 |

| Kentucky | 2,625 | 5,150 | 7,750 | 13,345 |

United States is the home to the overwhelming majority (98.35%) of

the Amish people. In 2019, Old Order communities were present in 31 U.S.

states. The total Amish population in United States as of June 2019 has stood at 336,235,

up 11,335 or 3.5%, compared to the previous year. Pennsylvania has the

largest population (79,200), followed by Ohio (76,200) and Indiana

(57,400), as of June 2019. The largest Amish settlements are in Lancaster County in southeastern Pennsylvania (39,255), Holmes County and adjacent counties in northeastern Ohio (36,755), and Elkhart and LaGrange counties in northeastern Indiana (25,660), as of June 2019. Nearly 50% of the population in Holmes County is Amish.

The largest concentration of Amish west of the Mississippi River is in Missouri, with other settlements in eastern Iowa and southeast Minnesota. The largest Amish settlements in Iowa are located near Kalona and Bloomfield. The largest settlement in Wisconsin is near Cashton with 13 congregations, i.e. about 2,000 people in 2009.

Because of rapid population growth in Amish communities, new

settlements are formed to obtain enough affordable farmland. Other

reasons for new settlements include locating in isolated areas that

support their lifestyle, moving to areas with cultures conducive to

their way of life, maintaining proximity to family or other Amish

groups, and sometimes to resolve church or leadership conflicts.

The adjacent table shows the eight states with the largest Amish population in the years 1992, 2000, 2010, and 2019.

Canada

Amish settlements are in four Canadian provinces: Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Manitoba, and New Brunswick. The majority of Old Order settlements is located in the province of Ontario, namely Oxford (Norwich Township) and Norfolk Counties. A small community is also established in Bruce County (Huron-Kinloss Township) near Lucknow.

| Area outside the U.S. | Amish pop. in 1992 | Amish pop. in 2010 | Amish pop. in 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada: | 2,295 | 4,725 | 5,665 |

| > Ontario | 2,295 | 4,725 | 5,340 |

| > Prince Edward Island | 0 | 0 | 205 |

| > Manitoba | 0 | 0 | 65 |

| > New Brunswick | 0 | 0 | 55 |

| Bolivia | 0 | 0 | 150 |

| Argentina | 0 | 0 | 50 |

In 2016, several dozen Old Order Amish families founded two new settlements in Kings County

in the province of Prince Edward Island. Increasing land prices in

Ontario had reportedly limited the ability of members in those

communities to purchase new farms. At about the same time a new settlement was founded near Perth-Andover in New Brunswick, only about 12 km from Amish settlements in Maine. In 2017, an Amish settlement was founded in Manitoba near Stuartburn.

Latin America

The first attempt by Old Order Amish to settle in Latin America was in Paradise Valley, near Galeana, Nuevo León, Mexico, but the settlement only lasted from 1923 to 1929. An Amish settlement was tried in Honduras from about 1968 to 1978, but this settlement failed too. In 2015, new settlements of New Order Amish were founded east of Catamarca, Argentina, and Colonia Naranjita, Bolivia, about 75 miles (121 km) southwest of Santa Cruz. Most of the members of these new communities come from Old Colony Mennonite background and have been living in the area for several decades.

Europe

In

Europe, no split occurred between Old Order Amish and Amish Mennonites;

like the Amish Mennonites in North America, the European Amish

assimilated into the Mennonite mainstream during the second half of the

19th century through the first decades of the 20th century. Eventually,

they dropped the word "Amish" from the names of their congregations and

lost their Amish identity and culture. The last European Amish

congregation joined the Mennonites in 1937 in Ixheim, today part of Zweibrücken in the Palatinate region.

Seekers and joiners

Only a few outsiders, so-called seekers, have ever joined the Amish. Since 1950, only some 75 people have joined and remained members of the Amish. Since 1990, some twenty people of Russian Mennonite background have joined the Amish in Aylmer, Ontario.

Two whole Christian communities have joined the Amish: The church at Smyrna, Maine, one of the five Christian Communities of Elmo Stoll after Stoll's death and the church at Manton, Michigan, which belonged to a community that was founded by Harry Wanner (1935–2012), a minister of Stauffer Old Order Mennonite background. The "Michigan Churches",

with which Smyrna and Manton affiliated, are said to be more open to

seekers and converts than other Amish churches. Most of the members of

these two para-Amish communities originally came from Plain churches, i.e. Old Order Amish, Old Order Mennonite, or Old German Baptist Brethren.

More people have tested Amish life for weeks, months, or even

years, but in the end decided not to join. Others remain close to the

Amish, but never think of joining.

Stephen Scott, himself a convert to the Old Order River Brethren, distinguishes four types of seekers:

- Checklist seekers are looking for a few certain specifications.

- Cultural seekers are more enchanted with the lifestyle of the Amish than with their religion.

- Spiritual utopian seekers are looking for true New Testament Christianity.

- Stability seekers come with emotional issues, often from dysfunctional families.

Health

Amish farm near Morristown, New York

Amish populations have higher incidences of particular conditions, including dwarfism, Angelman syndrome, and various metabolic disorders, as well as an unusual distribution of blood types. The Amish represent a collection of different demes or genetically closed communities. Although the Amish do not have higher rates of genetic disorders than the general population,

since almost all Amish descend from about 200 18th-century founders,

genetic disorders resulting from inbreeding exist in more isolated

districts (an example of the founder effect).

Some of these disorders are rare or unique, and are serious enough to

increase the mortality rate among Amish children. The Amish are aware of

the advantages of exogamy, but for religious reasons, marry only within their communities. The majority of Amish accepts these as Gottes Wille

(God's will); they reject the use of preventive genetic tests prior to

marriage and genetic testing of unborn children to discover genetic

disorders. When a child is born with a disorder, it is accepted into the

community and tasked with chores within their ability.

However, Amish are willing to participate in studies of genetic

diseases. Their extensive family histories are useful to researchers

investigating diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and macular degeneration.

While the Amish are at an increased risk for some genetic

disorders, researchers have found their tendency for clean living can

lead to better health. Overall cancer rates in the Amish are reduced and

tobacco-related cancers in Amish adults are 37% and non-tobacco-related

cancers are 72% of the rate for Ohio adults. The Amish are protected

against many types of cancer both through their lifestyle and through

genes that may reduce their susceptibility to cancer.

Even skin cancer rates are lower for Amish, even though many Amish make

their living working outdoors where they are exposed to sunlight. They

are typically covered and dressed by wearing wide-brimmed hats and long

sleeves which protect their skin.

Treating genetic problems is the mission of Clinic for Special Children in Strasburg, Pennsylvania, which has developed effective treatments for such problems as maple syrup urine disease,

a previously fatal disease. The clinic is embraced by most Amish,

ending the need for parents to leave the community to receive proper

care for their children, an action that might result in shunning.

Another clinic is DDC Clinic for Special Needs Children, located in Middlefield, Ohio, for special-needs children with inherited or metabolic disorders. The DDC Clinic provides treatment, research, and educational services to Amish and non-Amish children and their families.

People's Helpers is an Amish-organized network of mental health

caregivers who help families dealing with mental illness and recommend

professional counselors. Suicide rates for the Amish are about half that of the general population.

The Old Order Amish do not typically carry private commercial health insurance.

A handful of American hospitals, starting in the mid-1990s, created

special outreach programs to assist the Amish. In some Amish

communities, the church will collect money from its members to help pay

for medical bills of other members.

Although not forbidden, most Amish do not practice any form of birth control. They are against abortion and also find "artificial insemination, genetics, eugenics, and stem cell research" to be "inconsistent with Amish values and beliefs". However, some communities allow access to birth control to women whose health would be compromised by childbirth.

Amish life in the modern world

Traditional, Lancaster style Amish buggy

Amish school near Rebersburg, Pennsylvania

As time has passed, the Amish have felt pressures from the modern

world. Issues such as taxation, education, law and its enforcement, and

occasional discrimination and hostility are areas of difficulty.

The Amish way of life in general has increasingly diverged from

that of modern society. On occasion, this has resulted in sporadic

discrimination and hostility from their neighbors, such as throwing of

stones or other objects at Amish horse-drawn carriages on the roads.

The Amish do not usually educate their children past the eighth

grade, believing that the basic knowledge offered up to that point is

sufficient to prepare one for the Amish lifestyle. Almost no Amish go to

high school and college. In many communities, the Amish operate their

own schools, which are typically one-room schoolhouses with teachers

(usually young, unmarried women) from the Amish community. On May 19,

1972, Jonas Yoder and Wallace Miller of the Old Order Amish, and Adin

Yutzy of the Conservative Amish Mennonite Church were each fined $5 for

refusing to send their children, aged 14 and 15, to high school. In Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972), the Wisconsin Supreme Court overturned the conviction, and the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed this, finding the benefits of universal education were not sufficient justification to overcome scrutiny under the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment.

The Amish are subject to sales and property taxes. As they

seldom own motor vehicles, they rarely have occasion to pay motor

vehicle registration fees or spend money in the purchase of fuel for

vehicles.

Under their beliefs and traditions, generally the Amish do not agree

with the idea of Social Security benefits and have a religious objection

to insurance. On this basis, the United States Internal Revenue Service agreed in 1961 that they did not need to pay Social Security-related taxes. In 1965, this policy was codified into law.

Self-employed individuals in certain sects do not pay into or receive

benefits from the United States Social Security system. This exemption

applies to a religious group that is conscientiously opposed to

accepting benefits of any private or public insurance, provides a

reasonable level of living for its dependent members, and has existed

continuously since December 31, 1950.

The U.S. Supreme Court clarified in 1982 that Amish employers are not

exempt, but only those Amish individuals who are self-employed.

Publishing

In 1964, Pathway Publishers was founded by two Amish farmers to print more material about the Amish and Anabaptists in general. It is located in Lagrange, Indiana, and Aylmer, Ontario.

Pathway has become the major publisher of Amish school textbooks,

general-reading books, and periodicals. Also, a number of private

enterprises publish everything from general reading to reprints of

older literature that has been considered of great value to Amish

families. Some Amish read the Pennsylvania German newspaper Hiwwe wie Driwwe, and some of them even contribute dialect texts.

Similar groups

Groups that sprang from the same late 19th century Old Order Movement as the Amish share their Pennsylvania German heritage and often still retain similar features in dress. These Old Order groups include different subgroups of Old Order Mennonites, traditional Schwarzenau Brethren and Old Order River Brethren. The Noah Hoover Old Order Mennonites

are so similar in outward aspects to the Old Order Amish (dress,

beards, horse and buggy, extreme restrictions on modern technology,

Pennsylvania German language), that they are often perceived as Amish

and even called Amish.

Conservative "Russian" Mennonites and Hutterites

who also dress plain and speak German dialects emigrated from other

European regions at a different time with different German dialects,

separate cultures, and related but different religious traditions. Particularly, the Hutterites live communally and are generally accepting of modern technology.

The few remaining Plain Quakers are similar in manner and lifestyle, including their attitudes toward war, but are unrelated to the Amish. Early Quakers were influenced, to some degree, by the Anabaptists,

and in turn influenced the Amish in colonial Pennsylvania. Almost all

modern Quakers have since abandoned their traditional dress.

The Amish and the Native Americans

The Northkill Amish Settlement, established in 1740 in Berks County, Pennsylvania, was the first identifiable Amish community in the new world. During the French and Indian War, the so-called Hochstetler Massacre occurred: Local tribes attacked the Jacob Hochstetler homestead

in the Northkill settlement on September 19, 1757. The sons of the

family took their weapons but father Jacob did not allow them to shoot.

Jacob Sr.'s wife, Anna (Lorentz) Hochstetler, a daughter (name unknown)

and Jacob Jr. were killed by the Native Americans. Jacob Sr. and sons

Joseph and Christian were taken captive. Jacob escaped after about eight

months, but the boys were held for several years.

As early as 1809 Amish were farming side by side with Native American farmers in Pennsylvania. According to Cones Kupwah Snowflower, a Shawnee genealogist, the Amish

and Quakers were known to incorporate Native Americans into their

families to protect them from ill-treatment, especially after the Removal Act of 1832.

The Amish, as pacifists, did not engage in warfare with Native

Americans, nor displace them directly, but were among the European

immigrants whose arrival resulted in their displacement.

In 2012, the Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society collaborated

with the Native American community to construct a replica Iroquois

Longhouse.