Microscope

| |

| Uses | Small sample observation |

|---|---|

| Notable experiments | Discovery of cells |

| Related items | Optical microscope Electron microscope |

A microscope (from the Ancient Greek: μικρός, mikrós, "small" and σκοπεῖν, skopeîn, "to look" or "see") is an instrument used to see objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using such an instrument. Microscopic means invisible to the eye unless aided by a microscope.

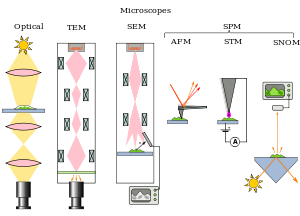

There are many types of microscopes, and they may be grouped in different ways. One way is to describe the way the instruments interact with a sample to create images, either by sending a beam of light or electrons to a sample in its optical path, or by scanning across, and a short distance from the surface of a sample using a probe. The most common microscope (and the first to be invented) is the optical microscope, which uses light to pass through a sample to produce an image. Other major types of microscopes are the fluorescence microscope, the electron microscope (both the transmission electron microscope and the scanning electron microscope) and the various types of scanning probe microscopes.

History

18th-century microscopes from the Musée des Arts et Métiers, Paris

Although objects resembling lenses date back 4000 years and there are Greek

accounts of the optical properties of water-filled spheres (5th century

BC) followed by many centuries of writings on optics, the earliest

known use of simple microscopes (magnifying glasses) dates back to the widespread use of lenses in eyeglasses in the 13th century. The earliest known examples of compound microscopes, which combine an objective lens near the specimen with an eyepiece to view a real image, appeared in Europe around 1620.

The inventor is unknown although many claims have been made over the

years. Several revolve around the spectacle-making centers in the Netherlands including claims it was invented in 1590 by Zacharias Janssen (claim made by his son) and/or Zacharias' father, Hans Martens, claims it was invented by their neighbor and rival spectacle maker, Hans Lippershey (who applied for the first telescope patent in 1608), and claims it was invented by expatriate Cornelis Drebbel who was noted to have a version in London in 1619. Galileo Galilei

(also sometimes cited as compound microscope inventor) seems to have

found after 1610 that he could close focus his telescope to view small

objects and, after seeing a compound microscope built by Drebbel

exhibited in Rome in 1624, built his own improved version. Giovanni Faber coined the name microscope for the compound microscope Galileo submitted to the Accademia dei Lincei in 1625 (Galileo had called it the "occhiolino" or "little eye").

Rise of modern light microscopes

Carl Zeiss binocular compound microscope, 1914

The first detailed account of the microscopic anatomy of organic tissue based on the use of a microscope did not appear until 1644, in Giambattista Odierna's L'occhio della mosca, or The Fly's Eye.

The microscope was still largely a novelty until the 1660s and

1670s when naturalists in Italy, the Netherlands and England began using

them to study biology. Italian scientist Marcello Malpighi, called the father of histology by some historians of biology, began his analysis of biological structures with the lungs. Robert Hooke's Micrographia had a huge impact, largely because of its impressive illustrations. A significant contribution came from Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

who achieved up to 300 times magnification using a simple single lens

microscope. He sandwiched a very small glass ball lens between the

holes in two metal plates riveted together, and with an

adjustable-by-screws needle attached to mount the specimen. Then, Van Leeuwenhoek re-discovered red blood cells (after Jan Swammerdam) and spermatozoa,

and helped popularise the use of microscopes to view biological

ultrastructure. On 9 October 1676, van Leeuwenhoek reported the

discovery of micro-organisms.

The performance of a light microscope depends on the quality and correct use of the condensor lens system to focus light on the specimen and the objective lens to capture the light from the specimen and form an image.

Early instruments were limited until this principle was fully

appreciated and developed from the late 19th to very early 20th century,

and until electric lamps were available as light sources. In 1893 August Köhler developed a key principle of sample illumination, Köhler illumination,

which is central to achieving the theoretical limits of resolution for

the light microscope. This method of sample illumination produces even

lighting and overcomes the limited contrast and resolution imposed by

early techniques of sample illumination. Further developments in sample

illumination came from the discovery of phase contrast by Frits Zernike in 1953, and differential interference contrast illumination by Georges Nomarski in 1955; both of which allow imaging of unstained, transparent samples.

Electron microscopes

Electron microscope constructed by Ernst Ruska in 1933

In the early 20th century a significant alternative to the light microscope was developed, an instrument that uses a beam of electrons rather than light to generate an image. The German physicist, Ernst Ruska, working with electrical engineer Max Knoll, developed the first prototype electron microscope in 1931, a transmission electron microscope

(TEM). The transmission electron microscope works on similar principles

to an optical microscope but uses electrons in the place of light and

electromagnets in the place of glass lenses. Use of electrons, instead

of light, allows for much higher resolution.

Development of the transmission electron microscope was quickly followed in 1935 by the development of the scanning electron microscope by Max Knoll.

Although TEMs were being used for research before WWII, and became

popular afterwards, the SEM was not commercially available until 1965.

Transmission electron microscopes became popular following the Second World War. Ernst Ruska, working at Siemens,

developed the first commercial transmission electron microscope and, in

the 1950s, major scientific conferences on electron microscopy started

being held. In 1965, the first commercial scanning electron microscope

was developed by Professor Sir Charles Oatley and his postgraduate student Gary Stewart, and marketed by the Cambridge Instrument Company as the "Stereoscan".

One of the latest discoveries made about using an electron microscope is the ability to identify a virus.

Since this microscope produces a visible, clear image of small

organelles, in an electron microscope there is no need for reagents to

see the virus or harmful cells, resulting in a more efficient way to

detect pathogens.

Scanning probe microscopes

From 1981 to 1983 Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer worked at IBM in Zurich, Switzerland to study the quantum tunnelling phenomenon. They created a practical instrument, a scanning probe microscope

from quantum tunnelling theory, that read very small forces exchanged

between a probe and the surface of a sample. The probe approaches the

surface so closely that electrons can flow continuously between probe

and sample, making a current from surface to probe. The microscope was

not initially well received due to the complex nature of the underlying

theoretical explanations. In 1984 Jerry Tersoff and D.R. Hamann, while at AT&T's Bell Laboratories in Murray Hill, New Jersey

began publishing articles that tied theory to the experimental results

obtained by the instrument. This was closely followed in 1985 with

functioning commercial instruments, and in 1986 with Gerd Binnig, Quate,

and Gerber's invention of the atomic force microscope, then Binnig's and Rohrer's Nobel Prize in Physics for the SPM.

New types of scanning probe microscope have continued to be

developed as the ability to machine ultra-fine probes and tips has

advanced.

Fluorescence microscopes

Fluorescence microscope with the filter cube turret above the objective lenses, coupled with a camera.

The most recent developments in light microscope largely centre on the rise of fluorescence microscopy in biology. During the last decades of the 20th century, particularly in the post-genomic era, many techniques for fluorescent staining of cellular structures were developed.

The main groups of techniques involve targeted chemical staining of

particular cell structures, for example, the chemical compound DAPI to label DNA, use of antibodies conjugated to fluorescent reporters, see

immunofluorescence, and fluorescent proteins, such as green fluorescent protein.

These techniques use these different fluorophores for analysis of cell

structure at a molecular level in both live and fixed samples.

The rise of fluorescence microscopy drove the development of a major modern microscope design, the confocal microscope. The principle was patented in 1957 by Marvin Minsky, although laser technology limited practical application of the technique. It was not until 1978 when Thomas and Christoph Cremer developed the first practical confocal laser scanning microscope and the technique rapidly gained popularity through the 1980s.

Super resolution microscopes

Much current research (in the early 21st century) on optical microscope techniques is focused on development of superresolution analysis of fluorescently labelled samples. Structured illumination can improve resolution by around two to four times and techniques like stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy are approaching the resolution of electron microscopes.

This occurs because the diffraction limit is occurred from light or

excitation, which makes the resolution must be doubled to become super

saturated. Stefan Hell was awarded the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for

the development of the STED technique, along with Eric Betzig and

William Moerner who adapted fluorescence microscopy for single-molecule

visualization.

X-ray microscopes

X-ray microscopes are instruments that use electromagnetic radiation

usually in the soft X-ray band to image objects. Technological advances

in X-ray lens optics in the early 1970s made the instrument a viable

imaging choice. They are often used in tomography

to produce three dimensional images of objects, including biological

materials that have not been chemically fixed. Currently research is

being done to improve optics for hard X-rays which have greater

penetrating power.

Types

Types of microscopes illustrated by the principles of their beam paths

Evolution of spatial resolution achieved with optical, transmission (TEM) and aberration-corrected electron microscopes (ACTEM).

Microscopes can be separated into several different classes. One

grouping is based on what interacts with the sample to generate the

image, i.e., light or photons (optical microscopes), electrons

(electron microscopes) or a probe (scanning probe microscopes).

Alternatively, microscopes can be classified based on whether they

analyze the sample via a scanning point (confocal optical microscopes,

scanning electron microscopes and scanning probe microscopes) or analyze

the sample all at once (wide field optical microscopes and transmission

electron microscopes).

Wide field optical microscopes and transmission electron microscopes both use the theory of lenses (optics for light microscopes and electromagnet lenses for electron microscopes) in order to magnify the image generated by the passage of a wave transmitted through the sample, or reflected by the sample. The waves used are electromagnetic (in optical microscopes) or electron beams (in electron microscopes). Resolution

in these microscopes is limited by the wavelength of the radiation used

to image the sample, where shorter wavelengths allow for a higher

resolution.

Scanning optical and electron microscopes, like the confocal

microscope and scanning electron microscope, use lenses to focus a spot

of light or electrons onto the sample then analyze the signals generated

by the beam interacting with the sample. The point is then scanned over

the sample to analyze a rectangular region. Magnification of the image

is achieved by displaying the data from scanning a physically small

sample area on a relatively large screen. These microscopes have the

same resolution limit as wide field optical, probe, and electron

microscopes.

Scanning probe microscopes also analyze a single point in the

sample and then scan the probe over a rectangular sample region to build

up an image. As these microscopes do not use electromagnetic or

electron radiation for imaging they are not subject to the same

resolution limit as the optical and electron microscopes described

above.

Optical

The most common type of microscope (and the first invented) is the optical microscope. This is an optical instrument containing one or more lenses producing an enlarged image of a sample placed in the focal plane. Optical microscopes have refractive glass (occasionally plastic or quartz),

to focus light on the eye or on to another light detector. Mirror-based

optical microscopes operate in the same manner. Typical magnification

of a light microscope, assuming visible range light, is up to 1250x with

a theoretical resolution limit of around 0.250 micrometres or 250 nanometres. This limits practical magnification to ~1500x. Specialized techniques (e.g., scanning confocal microscopy, Vertico SMI) may exceed this magnification but the resolution is diffraction

limited. The use of shorter wavelengths of light, such as ultraviolet,

is one way to improve the spatial resolution of the optical microscope,

as are devices such as the near-field scanning optical microscope.

Sarfus

is a recent optical technique that increases the sensitivity of a

standard optical microscope to a point where it is possible to directly

visualize nanometric films (down to 0.3 nanometre) and isolated

nano-objects (down to 2 nm-diameter). The technique is based on the use

of non-reflecting substrates for cross-polarized reflected light

microscopy.

Ultraviolet light enables the resolution of microscopic features as well as the imaging of samples that are transparent to the eye. Near infrared

light can be used to visualize circuitry embedded in bonded silicon

devices, since silicon is transparent in this region of wavelengths.

In fluorescence microscopy many wavelengths of light ranging from the ultraviolet to the visible can be used to cause samples to fluoresce, which allows viewing by eye or with specifically sensitive cameras.

Unstained cells viewed by typical brightfield (left) compared to phase-contrast microscopy (right).

Phase-contrast microscopy is an optical microscopy illumination technique in which small phase shifts in the light passing through a transparent specimen are converted into amplitude or contrast changes in the image. The use of phase contrast does not require staining to view the slide. This microscope technique made it possible to study the cell cycle in live cells.

The traditional optical microscope has more recently evolved into the digital microscope. In addition to, or instead of, directly viewing the object through the eyepieces, a type of sensor similar to those used in a digital camera is used to obtain an image, which is then displayed on a computer monitor. These sensors may use CMOS or charge-coupled device (CCD) technology, depending on the application.

Digital microscopy with very low light levels to avoid damage to vulnerable biological samples is available using sensitive photon-counting digital cameras. It has been demonstrated that a light source providing pairs of entangled photons may minimize the risk of damage to the most light-sensitive samples. In this application of ghost imaging

to photon-sparse microscopy, the sample is illuminated with infrared

photons, each of which is spatially correlated with an entangled partner

in the visible band for efficient imaging by a photon-counting camera.

Modern transmission electron microscope

Electron

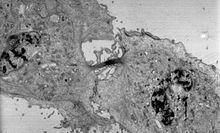

Transmission electron micrograph of a dividing cell undergoing cytokinesis

The two major types of electron microscopes are transmission electron microscopes (TEMs) and scanning electron microscopes (SEMs).

They both have series of electromagnetic and electrostatic lenses to

focus a high energy beam of electrons on a sample. In a TEM the

electrons pass through the sample, analogous to basic optical microscopy. This requires careful sample preparation, since electrons are scattered strongly by most materials. The samples must also be very thin (50 – 100 nm) in order for the electrons to pass through it. Cross-sections of cells stained with osmium and heavy metals reveal clear organelle membranes and proteins such as ribosomes. With a 0.1 nm level of resolution, detailed views of viruses (20 – 300 nm) and a strand of DNA (2 nm in width) can be obtained.

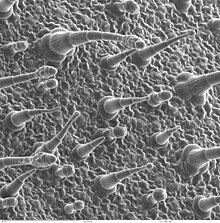

In contrast, the SEM has raster coils to scan the surface of bulk

objects with a fine electron beam. Therefore, the specimen do not

necessarily need to be sectioned, but require coating with a substance

such as a heavy metal. This allows three-dimensional views of the surface of samples.

Scanning probe

The different types of scanning probe microscopes arise from the many

different types of interactions that occur when a small probe is

scanned over and interacts with a specimen. These interactions or modes

can be recorded or mapped as function of location on the surface to form

a characterization map. The three most common types of scanning probe

microscopes are atomic force microscopes (AFM), near-field scanning optical microscopes (MSOM or SNOM, scanning near-field optical microscopy), and scanning tunneling microscopes (STM).

An atomic force microscope has a fine probe, usually of silicon or

silicon nitride, attached to a cantilever; the probe is scanned over the

surface of the sample, and the forces that cause an interaction between

the probe and the surface of the sample are measured and mapped. A

near-field scanning optical microscope is similar to an AFM but its

probe consists of a light source in an optical fiber covered with a tip

that has usually an aperture for the light to pass through. The

microscope can capture either transmitted or reflected light to measure

very localized optical properties of the surface, commonly of a

biological specimen. Scanning tunneling microscopes have a metal tip

with a single apical atom; the tip is attached to a tube through which a

current flows.

The tip is scanned over the surface of a conductive sample until a

tunneling current flows; the current is kept constant by computer

movement of the tip and an image is formed by the recorded movements of

the tip.

Leaf surface viewed by a scanning electron microscope.

Other types

Scanning acoustic microscopes use sound waves to measure variations in acoustic impedance. Similar to Sonar

in principle, they are used for such jobs as detecting defects in the

subsurfaces of materials including those found in integrated circuits.

On February 4, 2013, Australian engineers built a "quantum microscope"

which provides unparalleled precision.