| Bruxism | |

|---|---|

| |

| Attrition (tooth wear caused by tooth-to-tooth contact) can be a manifestation of bruxism. | |

| Specialty | Dentistry |

Bruxism is excessive teeth grinding or jaw clenching. It is an oral parafunctional activity; i.e., it is unrelated to normal function such as eating or talking. Bruxism is a common behavior; reports of prevalence range from 8% to 31% in the general population. Several symptoms are commonly associated with bruxism, including hypersensitive teeth, aching jaw muscles, headaches, tooth wear, and damage to dental restorations (e.g. crowns and fillings). Symptoms may be minimal, without patient awareness of the condition.

There are two main types of bruxism: one occurs during sleep (nocturnal bruxism) and one during wakefulness (awake bruxism). Dental damage may be similar in both types, but the symptoms of sleep bruxism tend to be worse on waking and improve during the course of the day, and the symptoms of awake bruxism may not be present at all on waking, and then worsen over the day. The causes of bruxism are not completely understood, but probably involve multiple factors. Awake bruxism is more common in females, whereas males and females are affected in equal proportions by sleep bruxism. Awake bruxism is thought to have different causes from sleep bruxism. Several treatments are in use, although there is little evidence of robust efficacy for any particular treatment.

Signs and symptoms

Most

people who brux are unaware of the problem, either because there are no

symptoms, or because the symptoms are not understood to be associated

with a clenching and grinding problem. The symptoms of sleep bruxism are

usually most intense immediately after waking, and then slowly abate,

and the symptoms of a grinding habit which occurs mainly while awake

tend to worsen through the day, and may not be present on waking. Bruxism may cause a variety of signs and symptoms, including:

View

from above of an anterior (front) tooth showing severe tooth wear which

has exposed the dentin layer (normally covered by enamel). The pulp

chamber is visible through the overlying dentin. Tertiary dentin will

have been laid down by the pulp in response to the loss of tooth

substance. Multiple fracture lines are also visible.

- Excessive tooth wear, particularly attrition, which flattens the occlusal (biting) surface, but also possibly other types of tooth wear such as abfraction, where notches form around the neck of the teeth at the gumline.

- Tooth fractures, and repeated failure of dental restorations (fillings, crowns, etc.).

- Hypersensitive teeth, (e.g. dental pain when drinking a cold liquid) caused by wearing away of the thickness of insulating layers of dentin and enamel around the dental pulp.

- Inflammation of the periodontal ligament of teeth, which may make them sore to bite on, and possibly also a degree of loosening of the teeth.

- A grinding or tapping noise during sleep, sometimes detected by a partner or a parent. This noise can be surprisingly loud and unpleasant, and can wake a sleeping partner. Noises are rarely associated with awake bruxism.

- Other parafunctional activity which may occur together with bruxism: cheek biting (which may manifest as morsicatio buccarum and/or linea alba), and/or lip biting.

- A burning sensation on the tongue, possibly related to a coexistent "tongue thrusting" parafunctional activity.

- Indentations of the teeth in the tongue ("crenated tongue" or "scalloped tongue").

- Hypertrophy of the muscles of mastication (increase in the size of the muscles that move the jaw), particularly the masseter muscle.

- Tenderness, pain or fatigue of the muscles of mastication, which may get worse during chewing or other jaw movement.

- Trismus (restricted mouth opening).

- Pain or tenderness of the temporomandibular joints, which may manifest as preauricular pain (in front of the ear), or pain referred to the ear (otalgia).

- Clicking of the temporomandibular joints.

- Headaches, particularly pain in the temples, caused by muscle pain associated with the temporalis muscle.

Bruxism is usually detected because of the effects of the process

(most commonly tooth wear and pain), rather than the process itself. The

large forces that can be generated during bruxism can have detrimental

effects on the components of masticatory system, namely the teeth, the periodontium and the articulation of the mandible

with the skull (the temporomandibular joints). The muscles of

mastication that act to move the jaw can also be affected since they are

being utilized over and above of normal function.

Tooth wear

Many

publications list tooth wear as a consequence of bruxism, but some

report a lack of a positive relationship between tooth wear and bruxism. Tooth wear caused by tooth-to-tooth contact is termed attrition.

This is the most usual type of tooth wear that occurs in bruxism, and

affects the occlusal surface (the biting surface) of the teeth. The

exact location and pattern of attrition depends on how the bruxism

occurs, e.g., when the canines and incisors

of the opposing arches are moved against each other laterally, by the

action of the medial pterygoid muscles, this can lead to the wearing

down of the incisal

edges of the teeth. To grind the front teeth, most people need to

posture their mandible forwards, unless there is an existing edge to

edge, class III incisal relationship. People with bruxism may also grind

their posterior teeth (back teeth), which wears down the cusps of the occlusal surface. Once tooth wear progresses through the enamel layer, the exposed dentin layer is softer and more vulnerable to wear and tooth decay.

If enough of the tooth is worn away or decayed, the tooth will

effectively be weakened, and may fracture under the increased forces

that occur in bruxism.

Abfraction

is another type of tooth wear that is postulated to occur with bruxism,

although some still argue whether this type of tooth wear is a reality.

Abfraction cavities are said to occur usually on the facial aspect of

teeth, in the cervical region as V-shaped defects caused by flexing of

the tooth under occlusal forces. It is argued that similar lesions can

be caused by long-term forceful toothbrushing. However, the fact that

the cavities are V-shaped does not suggest that the damage is caused by

toothbrush abrasion,

and that some abfraction cavities occur below the level of the gumline,

i.e., in an area shielded from toothbrush abrasion, supports the

validity of this mechanism of tooth wear. In addition to attrition, erosion is said to synergistically contribute to tooth wear in some bruxists, according to some sources.

Tooth mobility

The view that occlusal trauma (as may occur during bruxism) is a causative factor in gingivitis and periodontitis is not widely accepted.

It is thought that the periodontal ligament may respond to increased

occlusal (biting) forces by resorbing some of the bone of the alveolar

crest, which may result in increased tooth mobility, however these

changes are reversible if the occlusal force is reduced. Tooth movement that occurs during occlusal loading is sometimes termed fremitus. It is generally accepted that increased occlusal forces are able to increase the rate of progression of pre-existing periodontal disease (gum disease), however the main stay treatment is plaque control rather than elaborate occlusal adjustments.

It is also generally accepted that periodontal disease is a far more

common cause of tooth mobility and pathological tooth migration than any

influence of bruxism, although bruxism may much less commonly be

involved in both.

Pain

Most people with bruxism will experience no pain. The presence or degree of pain does not necessarily correlate with the severity of grinding or clenching. The pain in the muscles of mastication caused by bruxism can be likened to muscle pain after exercise.

The pain may be felt over the angle of the jaw (masseter) or in the

temple (temporalis), and may be described as a headache or an aching

jaw. Most (but not all) bruxism includes clenching force provided by

masseter and temporalis muscle groups; but some bruxers clench and grind

front teeth only, which involves minimal action of the masseter and

temporalis muscles. The temporomandibular joints themselves may also

become painful, which is usually felt just in front of the ear, or

inside the ear itself. Clicking of the jaw joint may also develop. The

forces exerted on the teeth are more than the periodontal ligament is

biologically designed to handle, and so inflammation may result. A tooth

may become sore to bite on, and further, tooth wear may reduce the

insulating width of enamel and dentin that protects the pulp of the

tooth and result in hypersensitivity, e.g. to cold stimuli.

The relationship of bruxism with temporomandibular joint dysfunction

(TMD, or temporomandibular pain dysfunction syndrome) is debated. Many

suggest that sleep bruxism can be a causative or contributory factor to

pain symptoms in TMD. Indeed, the symptoms of TMD overlap with those of bruxism. Others suggest that there is no strong association between TMD and bruxism.

A systematic review investigating the possible relationship concluded

that when self-reported bruxism is used to diagnose bruxism, there is a

positive association with TMD pain, and when stricter diagnostic

criteria for bruxism are used, the association with TMD symptoms is much

lower. In severe, chronic cases, bruxism can lead to myofascial pain and arthritis of the temporomandibular joints.

Causes

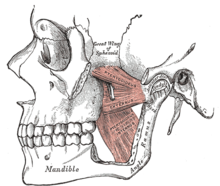

The left temporalis muscle

The

left medial pterygoid muscle, and the left lateral pterygoid muscle

above it, shown on the medial surface of the mandbilar ramus, which has

been partially removed along with a section of the zygomatic arch

The left masseter muscle (red highlight), shown partially covered by superficial muscles

The muscles of mastication (the temporalis, masseter, medial and

lateral pterygoid muscles) are paired on either side and work together

to move the mandible, which hinges and slides around its dual

articulation with the skull at the temporomandibular joints. Some of the

muscles work to elevate the mandible (close the mouth), and others also

are involved in lateral (side to side), protrusive or retractive

movements. Mastication

(chewing) is a complex neuromuscular activity that can be controlled

either by subconscious processes or by conscious processes. In

individuals without bruxism or other parafunctional activities, during

wakefulness the jaw is generally at rest and the teeth are not in

contact, except while speaking, swallowing or chewing. It is estimated

that the teeth are in contact for less than 20 minutes per day, mostly

during chewing and swallowing. Normally during sleep, the voluntary

muscles are inactive due to physiologic motor paralysis, and the jaw is

usually open.

Some bruxism activity is rhythmic with bite force pulses of

tenths of a second (like chewing), and some have longer bite force

pulses of 1 to 30 seconds (clenching). Some individuals clench without

significant lateral movements. Bruxism can also be regarded as a

disorder of repetitive, unconscious contraction of muscles. This

typically involves the masseter muscle and the anterior portion of the

temporalis (the large outer muscles that clench), and the lateral

pterygoids, relatively small bilateral muscles that act together to

perform sideways grinding.

The cause of bruxism is largely unknown, but it is generally accepted to have multiple possible causes. Bruxism is a parafunctional activity, but it is debated whether this represents a subconscious habit or is entirely involuntary. The relative importance of the various identified possible causative factors is also debated.

Awake bruxism is thought to be usually semivoluntary, and often

associated with stress caused by family responsibilities or work

pressures. Some suggest that in children, bruxism may occasionally represent a response to earache or teething. Awake bruxism usually involves clenching (sometimes the term "awake clenching" is used instead of awake bruxism), but also possibly grinding, and is often associated with other semivoluntary oral habits such as cheek biting, nail biting,

chewing on a pen or pencil absent mindedly, or tongue thrusting (where

the tongue is pushed against the front teeth forcefully).

There is evidence that sleep bruxism is caused by mechanisms related to the central nervous system, involving sleep arousal and neurotransmitter abnormalities. Underlying these factors may be psychosocial factors including daytime stress which is disrupting peaceful sleep.

Sleep bruxism is mainly characterized by "rhythmic masticatory muscle

activity" (RMMA) at a frequency of about once per second, and also with

occasional tooth grinding. It has been shown that the majority (86%) of sleep bruxism episodes occur during periods of sleep arousal.

One study reported that sleep arousals which were experimentally

induced with sensory stimulation in sleeping bruxists triggered episodes

of sleep bruxism.

Sleep arousals are a sudden change in the depth of the sleep stage, and

may also be accompanied by increased heart rate, respiratory changes

and muscular activity, such as leg movements.

Initial reports have suggested that episodes of sleep bruxism may be

accompanied by gastroesophageal reflux, decreased esophageal pH (acidity), swallowing, and decreased salivary flow. Another report suggested a link between episodes of sleep bruxism and a supine sleeping position (lying face up).

Disturbance of the dopaminergic system in the central nervous

system has also been suggested to be involved in the etiology of

bruxism.

Evidence for this comes from observations of the modifying effect of

medications which alter dopamine release on bruxing activity, such as

levodopa, amphetamines or nicotine. Nicotine

stimulates release of dopamine, which is postulated to explain why

bruxism is twice as common in smokers compared to non-smokers.

Psychosocial factors

Many

studies have reported significant psychosocial risk factors for

bruxism, particularly a stressful lifestyle, and this evidence is

growing, but still not conclusive. Some consider emotional stress to be the main triggering factor.

It has been reported that persons with bruxism respond differently to

depression, hostility and stress compared to people without bruxism.

Stress has a stronger relationship to awake bruxism, but the role of

stress in sleep bruxism is less clear, with some stating that there is

no evidence for a relationship with sleep bruxism. However, children with sleep bruxism have been shown to have greater levels of anxiety than other children. People aged 50 with bruxism are more likely to be single and have a high level of education. Work-related stress and irregular work shifts may also be involved. Personality traits are also commonly discussed in publications concerning the causes of bruxism, e.g. aggressive, competitive or hyperactive personality types. Some suggest that suppressed anger or frustration can contribute to bruxism.

Stressful periods such as examinations, family bereavement, marriage,

divorce, or relocation have been suggested to intensify bruxism. Awake

bruxism often occurs during periods of concentration such as while

working at a computer, driving or reading. Animal studies have also

suggested a link between bruxism and psychosocial factors. Rosales et

al. electrically shocked lab rats,

and then observed high levels of bruxism-like muscular activity in rats

that were allowed to watch this treatment compared to rats that did not

see it. They proposed that the rats who witnessed the electrical

shocking of other rats were under emotional stress which may have caused

the bruxism-like behavior.

Genetic factors

Some research suggests that there may be a degree of inherited susceptibility to develop sleep bruxism.

21–50% of people with sleep bruxism have a direct family member who had

sleep bruxism during childhood, suggesting that there are genetic

factors involved, although no genetic markers have yet been identified.

Offspring of people who have sleep bruxism are more likely to also have

sleep bruxism than children of people who do not have bruxism, or

people with awake bruxism rather than sleep bruxism.

Medications

Certain

stimulant drugs, including both prescribed and recreational drugs are

thought by some to cause the development of bruxism, however others argue that there is insufficient evidence to draw such a conclusion. Examples may include dopamine agonists, dopamine antagonists, tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, alcohol, cocaine, and amphetamines (including those taken for medical reasons).

In some reported cases where bruxism is thought to have been initiated

by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, decreasing the dose resolved

the side effect.

Other sources state that reports of selective serotonin reuptake

inhibitors causing bruxism are rare, or only occur with long-term use.

Specific examples include levodopa (when used in the long term, as in Parkinson's disease), fluoxetine, metoclopramide, lithium, cocaine, venlafaxine, citalopram, fluvoxamine, methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), methylphenidate (used in attention deficit hyperactive disorder), and gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) and similar gamma-aminobutyric acid-inducing analogues such as phenibut. Bruxism can also be exacerbated by excessive consumption of caffeine, as in coffee, tea or chocolate. Bruxism has also been reported to occur commonly comorbid with drug addiction. Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ecstasy) has been reported to be associated with bruxism,

which occurs immediately after taking the drug and for several days

afterwards. Tooth wear in people who take ecstasy is also frequently

much more severe than in people with bruxism not associated with

ecstasy.

Occlusal factors

Occlusion is defined most simply as "contacts between teeth", and is the meeting of teeth during biting and chewing. The term does not imply any disease. Malocclusion

is a medical term referring to less than ideal positioning of the upper

teeth relative to the lower teeth, which can occur both when the upper

jaw is ideally proportioned to the lower jaw, or where there is a

discrepancy between the size of the upper jaw relative to the lower jaw.

Malocclusion of some sort is so common that the concept of an "ideal

occlusion" is called into question, and it can be considered "normal to

be abnormal".

An occlusal interference may refer to a problem which interferes with

the normal path of the bite, and is usually used to describe a localized

problem with the position or shape of a single tooth or group of teeth.

A premature contact is one part of the bite meeting sooner than

other parts, meaning that the rest of the teeth meet later or are held

open, e.g., a new dental restoration on a tooth (e.g., a crown) which

has a slightly different shape or position to the original tooth may

contact too soon in the bite. A deflective contact/interference

is an interference with the bite that changes the normal path of the

bite. A common example of a deflective interference is an over-erupted

upper wisdom tooth, often because the lower wisdom tooth has been removed or is impacted.

In this example, when the jaws are brought together, the lower back

teeth contact the prominent upper wisdom tooth before the other teeth,

and the lower jaw has to move forward to allow the rest of the teeth to

meet. The difference between a premature contact and a deflective

interference is that the latter implies a dynamic abnormality in the

bite.

Historically, many believed that problems with the bite were the sole cause for bruxism.

It was often claimed that a person would grind at the interfering area

in a subconscious, instinctive attempt to wear this down and "self

equiliberate" their occlusion. However, occlusal interferences are

extremely common and usually do not cause any problems. It is unclear

whether people with bruxism tend to notice problems with the bite

because of their clenching and grinding habit, or whether these act as a

causative factor in the development of the condition. In sleep bruxism

especially, there is no evidence that removal of occlusal interferences

has any impact on the condition. People with no teeth at all who wear dentures can still suffer from bruxism,

although dentures also often change the original bite. Most modern

sources state that there is no relationship, or at most a minimal

relationship, between bruxism and occlusal factors.

The findings of one study, which used self-reported tooth grinding

rather than clinical examination to detect bruxism, suggested that there

may be more of a relationship between occlusal factors and bruxism in

children.

However, the role of occlusal factors in bruxism cannot be completely

discounted due to insufficient evidence and problems with the design of

studies.

A minority of researchers continue to claim that various adjustments to

the mechanics of the bite are capable of curing bruxism.

Possible associations

Several

associations between bruxism and other conditions, usually neurological

or psychiatric disorders, have rarely been reported, with varying

degrees of evidence (often in the form of case reports). Examples include:

- Acrodynia

- Atypical facial pain

- Autism

- Cerebral palsy

- Disturbed sleep patterns and other sleep disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnea, snoring, moderate daytime sleepiness, and insomnia

- Down syndrome

- Dyskinesias

- Epilepsy

- Eustachian tube dysfunction

- Infarction in the basal ganglia

- Intellectual disability, particularly in children

- Leigh disease

- Meningococcal septicaemia

- Multiple system atrophy

- Oromandibular dystonia

- Parkinson's diseases, (possibly due to long-term therapy with levodopa causing dopaminergic dysfunction)

- Rett syndrome

- Torus mandibularis and buccal exostosis

- Trauma, e.g. brain injury or coma

Diagnosis

Early

diagnosis of bruxism is advantageous, but difficult. Early diagnosis

can prevent damage that may be incurred and the detrimental effect on quality of life. A diagnosis of bruxism is usually made clinically,[11] and is mainly based on the person's history

(e.g. reports of grinding noises) and the presence of typical signs and

symptoms, including tooth mobility, tooth wear, masseteric hypertrophy,

indentations on the tongue, hypersensitive teeth (which may be

misdiagnosed as reversible pulpitis), pain in the muscles of mastication, and clicking or locking of the temporomandibular joints. Questionnaires can be used to screen for bruxism in both the clinical and research settings.

For tooth grinders who live in same household with other people,

diagnosis of grinding is straightforward: Housemates or family members

would advise a bruxer of recurrent grinding. Grinders who live alone

can likewise resort to a sound-activated tape recorder. To confirm the

condition of clenching, on the other hand, bruxers may rely on such

devices as the Bruxchecker,[32] Bruxcore, or a beeswax-bearing biteplate.

The Individual (personal) Tooth-Wear Index was developed to

objectively quantify the degree of tooth wear in an individual, without

being affected by the number of missing teeth.

Bruxism is not the only cause of tooth wear. Another possible cause of

tooth wear is acid erosion, which may occur in people who drink a lot of

acidic liquids such as concentrated fruit juice, or in people who

frequently vomit or regurgitate stomach acid, which itself can occur for

various reasons. People also demonstrate a normal level of tooth wear,

associated with normal function. The presence of tooth wear only

indicates that it had occurred at some point in the past, and does not

necessarily indicate that the loss of tooth substance is ongoing. People

who clench and perform minimal grinding will also not show much tooth

wear. Occlusal splints are usually employed as a treatment for bruxism,

but they can also be of diagnostic use, e.g. to observe the presence or

absence of wear on the splint after a certain period of wearing it at

night.

The most usual trigger in sleep bruxism that leads a person to

seek medical or dental advice is being informed by sleeping partner of

unpleasant grinding noises during sleep.

The diagnosis of sleep bruxism is usually straightforward, and involves

the exclusion of dental diseases, temporomandibular disorders, and the

rhythmic jaw movements that occur with seizure disorders (e.g.

epilepsy). This usually involves a dental examination, and possibly electroencephalography if a seizure disorder is suspected. Polysomnography shows increased masseter and temporalis muscular activity during sleep. Polysomnography may involve electroencephalography, electromyography, electrocardiography,

air flow monitoring and audio–video recording. It may be useful to help

exclude other sleep disorders; however, due to the expense of the use

of a sleep lab, polysomnography is mostly of relevance to research

rather than routine clinical diagnosis of bruxism.

Tooth wear may be brought to the person's attention during

routine dental examination. With awake bruxism, most people will often

initially deny clenching and grinding because they are unaware of the

habit. Often, the person may re-attend soon after the first visit and

report that they have now become aware of such a habit.

Several devices have been developed that aim to objectively

measure bruxism activity, either in terms of muscular activity or bite

forces. They have been criticized for introducing a possible change in

the bruxing habit, whether increasing or decreasing it, and are

therefore poorly representative to the native bruxing activity.

These are mostly of relevance to research, and are rarely used in the

routine clinical diagnosis of bruxism. Examples include the "Bruxcore

Bruxism-Monitoring Device" (BBMD, "Bruxcore Plate"), the "intra-splint

force detector" (ISFD), and electromyographic devices to measure masseter or temporalis muscle activity (e.g. the "BiteStrip", and the "Grindcare").

ICSD-R diagnostic criteria

The ICSD-R listed diagnostic criteria for sleep bruxism. The minimal criteria include both of the following:

- A. symptom of tooth-grinding or tooth-clenching during sleep, and

- B. One or more of the following:

- Abnormal tooth wear

- Grinding sounds

- Discomfort of the jaw muscles

With the following criteria supporting the diagnosis:

- C. polysomnography shows both:

- Activity of jaw muscles during sleep

- No associated epileptic activity

- D. No other medical or mental disorders (e.g., sleep-related epilepsy, which may cause abnormal movement during sleep).

- E. The presence of other sleep disorders (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea syndrome).

Definition examples

Bruxism is derived from the Greek word βρύκειν (brykein) "to bite, or to gnash, grind the teeth". People who suffer from bruxism are called bruxists or bruxers and the verb itself is "to brux". There is no widely accepted definition of bruxism. Examples of definitions include:

"Bruxism is a repetitive jaw-muscle activity characterized by clenching or grinding of the teeth and/or by bracing or thrusting of the mandible. Bruxism has two distinct circadian manifestations: it can occur during sleep (indicated as sleep bruxism) or during wakefulness (indicated as awake bruxism)."

All forms of bruxism entail forceful contact between the biting surfaces of the upper and lower teeth. In grinding and tapping this contact involves movement of the mandible and unpleasant sounds which can often awaken sleeping partners and even people asleep in adjacent rooms. Clenching (or clamping), on the other hand, involves inaudible, sustained, forceful tooth contact unaccompanied by mandibular movements.

"A movement disorder of the masticatory system characterized by teeth-grinding and clenching during sleep as well as wakefulness."

"Non-functional contact of the mandibular and maxillary teeth resulting in clenching or tooth grinding due to repetitive, unconscious contraction of the masseter and temporalis muscles."

"Parafunctional grinding of teeth or an oral habit consisting of involuntary rhythmic or spasmodic non-functional gnashing, grinding or clenching of teeth in other than chewing movements of the mandible which may lead to occlusal trauma."

"Periodic repetitive clenching or rhythmic forceful grinding of the teeth."

Classification by temporal pattern

| Sleep bruxism | Awake bruxism | |

| Occurrence | While asleep, mostly during periods of sleep arousal | While awake |

| Time–intensity relationship | Pain worst on waking, then slowly gets better | Pain worsens throughout the day, may not be present on waking |

| Noises | Commonly associated | Rarely associated |

| Activity | Clenching and grinding | Usually clenching, occasionally clenching and grinding |

| Relationship with stress | Unclear, little evidence of a relationship | Stronger evidence for a relationship, but not conclusive |

| Prevalence (general population) | 9.7–15.9% | 22.1–31% |

| Gender distribution | Equal gender distribution | Mostly females |

| Heritability | Some evidence | Unclear |

Bruxism can be subdivided into two types based upon when the

parafunctional activity occurs – during sleep ("sleep bruxism"), or

while awake ("awake bruxism").

This is the most widely used classification since sleep bruxism

generally has different causes to awake bruxism, although the effects on

the condition on the teeth may be the same.

The treatment is also often dependent upon whether the bruxism happens

during sleep or while awake, e.g., an occlusal splint worn during sleep

in a person who only bruxes when awake will probably have no benefit. Some have even suggested that sleep bruxism is an entirely different disorder and is not associated with awake bruxism. Awake bruxism is sometimes abbreviated to AB, and is also termed "diurnal bruxism", DB, or "daytime bruxing". Sleep bruxism is sometimes abbreviated to SB, and is also termed "sleep-related bruxism", "nocturnal bruxism", or "nocturnal tooth grinding". According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders

revised edition (ICSD-R), the term "sleep bruxism" is the most

appropriate since this type occurs during sleep specifically rather than

being associated with a particular time of day, i.e., if a person with

sleep bruxism were to sleep during the day and stay awake at night then

the condition would not occur during the night but during the day.

The ICDS-R defined sleep bruxism as "a stereotyped movement disorder

characterized by grinding or clenching of the teeth during sleep", classifying it as a parasomnia. The second edition (ICSD-2) however reclassified bruxism to a "sleep related movement disorder" rather than a parasomnia.

Classification by cause

Alternatively, bruxism can be divided into primary bruxism (also termed "idiopathic bruxism"), where the disorder is not related to any other medical condition, or secondary bruxism, where the disorder is associated with other medical conditions. Secondary bruxism includes iatrogenic

causes, such as the side effect of prescribed medications. Another

source divides the causes of bruxism into three groups, namely central

or pathophysiological factors, psychosocial factors and peripheral

factors. The World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases 10th revision does not have an entry called bruxism, instead listing "tooth grinding" under somatoform disorders. To describe bruxism as a purely somatoform disorder does not reflect the mainstream, modern view of this condition.

Classification by severity

The

ICSD-R described three different severities of sleep bruxism, defining

mild as occurring less than nightly, with no damage to teeth or

psychosocial impairment; moderate as occurring nightly, with mild

impairment of psychosocial functioning; and severe as occurring nightly,

and with damage to the teeth, tempormandibular disorders and other

physical injuries, and severe psychosocial impairment.

Classification by duration

The

ICSD-R also described three different types of sleep bruxism according

to the duration the condition is present, namely acute, which lasts for

less than one week; subacute, which lasts for more than a week and less

than one month; and chronic which lasts for over a month.

Management

Treatment

for bruxism revolves around repairing the damage to teeth that has

already occurred, and also often, via one or more of several available

methods, attempting to prevent further damage and manage symptoms, but

there is no widely accepted, best treatment. Since bruxism is not

life-threatening, and there is little evidence of the efficacy of any treatment,

it has been recommended that only conservative treatment which is

reversible and that carries low risk of morbidity should be used. The main treatments that have been described in awake and sleep bruxism are described below.

Dental treatment

Bruxism

can cause significant tooth wear if it is severe, and sometimes dental

restorations (crowns, fillings etc.) are damaged or lost, sometimes

repeatedly.

Most dentists therefore prefer to keep dental treatment in people with

bruxism very simple and only carry it out when essential, since any

dental work is likely to fail in the long term. Dental implants, dental ceramics such as Emax crowns and complex bridgework for example are relatively contraindicated in bruxists.

In the case of crowns, the strength of the restoration becomes more

important, sometimes at the cost of aesthetic considerations. E.g. a

full coverage gold crown, which has a degree of flexibility and also

involves less removal (and therefore less weakening) of the underlying

natural tooth may be more appropriate than other types of crown which

are primarily designed for esthetics rather than durability. Porcelain veneers on the incisors are particularly vulnerable to damage, and sometimes a crown can be perforated by occlusal wear.

Dental guards and occlusal splints

Occlusal splints (also termed dental guards)

are commonly prescribed, mainly by dentists and dental specialists, as a

treatment for bruxism. Proponents of their use claim many benefits,

however when the evidence is critically examined in systematic reviews

of the topic, it is reported that there is insufficient evidence to show

that occlusal splints are effective for sleep bruxism.

Furthermore, occlusal splints are probably ineffective for awake bruxism,

since they tend to be worn only during sleep. However, occlusal splints

may be of some benefit in reducing the tooth wear that may accompany

bruxism,

but by mechanically protecting the teeth rather than reducing the

bruxing activity itself. In a minority of cases, sleep bruxism may be

made worse by an occlusal splint. Some patients will periodically return

with splints with holes worn through them, either because the bruxism

is aggravated, or unaffected by the presence of the splint. When

tooth-to-tooth contact is possible through the holes in a splint, it is

offering no protection against tooth wear and needs to be replaced.

Occlusal splints are divided into partial or full-coverage

splints according to whether they fit over some or all of the teeth.

They are typically made of plastic (e.g. acrylic)

and can be hard or soft. A lower appliance can be worn alone, or in

combination with an upper appliance. Usually lower splints are better

tolerated in people with a sensitive gag reflex. Another problem with

wearing a splint can be stimulation of salivary flow, and for this

reason some advise to start wearing the splint about 30 mins before

going to bed so this does not lead to difficulty falling asleep. As an

added measure for hypersensitive teeth in bruxism, desensitizing

toothpastes (e.g. containing strontium chloride)

can be applied initially inside the splint so the material is in

contact with the teeth all night. This can be continued until there is

only a normal level of sensitivity from the teeth, although it should be

remembered that sensitivity to thermal stimuli is also a symptom of pulpitis, and may indicate the presence of tooth decay rather than merely hypersensitive teeth.

Splints may also reduce muscle strain by allowing the upper and

lower jaw to move easily with respect to each other. Treatment goals

include: constraining the bruxing pattern to avoid damage to the temporomandibular joints;

stabilizing the occlusion by minimizing gradual changes to the

positions of the teeth, preventing tooth damage and revealing the extent

and patterns of bruxism through examination of the markings on the

splint's surface. A dental guard is typically worn during every night's

sleep on a long-term basis. However, a meta-analysis of occlusal splints

(dental guards) used for this purpose concluded "There is not enough

evidence to state that the occlusal splint is effective for treating

sleep bruxism."

A repositioning splint is designed to change the patient's occlusion, or bite.

The efficacy of such devices is debated. Some writers propose that

irreversible complications can result from the long-term use of

mouthguards and repositioning splints. Random controlled trials with

these type devices generally show no benefit over other therapies.

Another partial splint is the nociceptive trigeminal inhibition tension suppression system

(NTI-TSS) dental guard. This splint snaps onto the front teeth only. It

is theorized to prevent tissue damages primarily by reducing the bite

force from attempts to close the jaw normally into a forward twisting of

the lower front teeth. The intent is for the brain to interpret the

nerve sensations as undesirable, automatically and subconsciously

reducing clenching force. However, there may be potential for the

NTI-TSS device to act as a Dahl appliance,

holding the posterior teeth out of occlusion and leading to their

over-eruption, deranging the occlusion (i.e. it may cause the teeth to

move position). This is far more likely if the appliance is worn for

excessive periods of time, which is why NTI type appliances are designed

for night time use only, and ongoing follow-ups are recommended.

A mandibular advancement device (normally used for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea) may reduce sleep bruxism, although its use may be associated with discomfort.

Psychosocial interventions

Given

the strong association between awake bruxism and psychosocial factors

(the relationship between sleep bruxism and psychosocial factors being

unclear), the role of psychosocial interventions could be argued to be

central to the management. The most simple form of treatment is

therefore reassurance that the condition does not represent a serious

disease, which may act to alleviate contributing stress.

Sleep hygiene education should be provided by the clinician, as

well as a clear and short explanation of bruxism (definition, causes and

treatment options). Relaxation and tension-reduction have not been found to reduce bruxism symptoms, but have given patients a sense of well-being. One study has reported less grinding and reduction of EMG activity after hypnotherapy.

Other interventions include relaxation techniques, stress

management, behavioural modification, habit reversal and hypnosis (self

hypnosis or with a hypnotherapist). Cognitive behavioral therapy has been recommended by some for treatment of bruxism.

In many cases awake bruxism can be reduced by using reminder

techniques. Combined with a protocol sheet this can also help to

evaluate in which situations bruxism is most prevalent.

Medication

Many different medications have been used to treat bruxism, including benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, beta blockers, dopamine agents, antidepressants, muscle relaxants,

and others. However, there is little, if any, evidence for their

respective and comparative efficacies with each other and when compared

to a placebo. A multiyear systematic review to investigate the evidence for drug treatments in sleep bruxism published in 2014 (Pharmacotherapy for Sleep Bruxism. Macedo, et al.) found "insufficient evidence on the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy for the treatment of sleep bruxism."

Specific drugs that have been studied in sleep bruxism are clonazepam, levodopa, amitriptyline, bromocriptine, pergolide, clonidine, propranolol, and l-tryptophan,

with some showing no effect and others appear to have promising initial

results; however, it has been suggested that further safety testing is

required before any evidence-based clinical recommendations can be made. When bruxism is related to the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in depression, adding buspirone has been reported to resolve the side effect.

Tricyclic antidepressants have also been suggested to be preferable to

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in people with bruxism, and may

help with the pain.

Botulinum toxin

Botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) is used as a treatment for bruxism, however there is only one randomized control trial which has reported that BoNT reduces the myofascial pain symptoms.

This scientific study was based on thirty people with bruxism who

received BoNT injections into the muscles of mastication and a control

group of people with bruxism who received placebo injections.

Normally multiple trials with larger cohorts are required to make any

firm statement about the efficacy of a treatment. In 2013, a further

randomized control trial investigating BoNT in bruxism started. There is also little information available about the safety and long term followup of this treatment for bruxism.

Botulinum toxin causes muscle paralysis/atrophy by inhibition of acetylcholine release at neuromuscular junctions.

BoNT injections are used in bruxism on the theory that a dilute

solution of the toxin will partially paralyze the muscles and lessen

their ability to forcefully clench and grind the jaw, while aiming to

retain enough muscular function to enable normal activities such as

talking and eating. This treatment typically involves five or six

injections into the masseter and temporalis muscles, and less often into

the lateral pterygoids (given the possible risk of decreasing the

ability to swallow) taking a few minutes per side. The effects may be

noticeable by the next day, and they may last for about three months.

Occasionally, adverse effects may occur, such as bruising, but this is

quite rare. The dose of toxin used depends upon the person, and a higher

dose may be needed in people with stronger muscles of mastication. With

the temporary and partial muscle paralysis, atrophy of disuse may

occur, meaning that the future required dose may be smaller or the

length of time the effects last may be increased.

Biofeedback

Biofeedback

is a process or device that allows an individual to become aware of,

and alter physiological activity with the aim of improving health.

Although the evidence of biofeedback has not been tested for awake

bruxism, there is recent evidence for the efficacy of biofeedback in the

management of nocturnal bruxism in small control groups.

Electromyographic monitoring devices of the associated muscle groups

tied with automatic alerting during periods of clenching and grinding

have been prescribed for awake bruxism. Dental appliances with capsules

that break and release a taste stimulus when enough force is applied

have also been described in sleep bruxism, which would wake the person

from sleep in an attempt to prevent bruxism episodes. "Large scale, double-blind, experiment confirming the effectiveness of this approach have yet to be carried out."

Occlusal adjustment/reorganization

As

an alternative to simply reactively repairing the damage to teeth and

conforming to the existing occlusal scheme, occasionally some dentists

will attempt to reorganize the occlusion in the belief that this may

redistribute the forces and reduce the amount of damage inflicted on the

dentition. Sometimes termed "occlusal rehabilitation" or "occlusal

equilibration",

this can be a complex procedure, and there is much disagreement between

proponents of these techniques on most of the aspects involved,

including the indications and the goals. It may involve orthodontics, restorative dentistry or even orthognathic surgery.

Some have criticized these occlusal reorganizations as having no

evidence base, and irreversibly damaging the dentition on top of the

damage already caused by bruxism.

Epidemiology

There

is a wide variation in reported epidemiologic data for bruxism, and

this is largely due to differences in the definition, diagnosis and

research methodologies of these studies. E.g. several studies use

self-reported bruxism as a measure of bruxism, and since many people

with bruxism are not aware of their habit, self-reported tooth grinding

and clenching habits may be a poor measure of the true prevalence.

The ICSD-R states that 85–90% of the general population grind

their teeth to a degree at some point during their life, although only

5% will develop a clinical condition. Some studies have reported that awake bruxism affects females more commonly than males, while in sleep bruxism, males and females are affected equally.[

Children are reported to brux as commonly as adults. It is

possible for sleep bruxism to occur as early as the first year of life –

after the first teeth (deciduous incisors) erupt into the mouth, and

the overall prevalence in children is about 14–20%. The ICSD-R states that sleep bruxism may occur in over 50% of normal infants. Often sleep bruxism develops during adolescence, and the prevalence in 18- to 29-year-olds is about 13%.

The overall prevalence in adults is reported to be 8%, and people over

the age of 60 are less likely to be affected, with the prevalence

dropping to about 3% in this group.

A 2013 systematic review of the epidemiologic reports of bruxism

concluded a prevalence of about 22.1–31% for awake bruxism, 9.7–15.9%

for sleep bruxism, and an overall prevalence of about 8–31.4% of bruxism

generally. The review also concluded that overall, bruxism affects

males and females equally, and affects elderly people less commonly.

History

"La bruxomanie" (a French term, translates to bruxomania) was suggested by Marie Pietkiewics in 1907. In 1931, Frohman first coined the term bruxism.

Occasionally recent medical publications will use the word bruxomania

with bruxism, to denote specifically bruxism that occurs while awake;

however, this term can be considered historical and the modern

equivalent would be awake bruxism or diurnal bruxism. It has been shown

that the type of research into bruxism has changed over time. Overall

between 1966 and 2007, most of the research published was focused on

occlusal adjustments and oral splints. Behavioral approaches in research

declined from over 60% of publications in the period 1966–86 to about

10% in the period 1997–2007.

In the 1960s, a periodontist named Sigurd Peder Ramfjord championed the

theory that occlusal factors were responsible for bruxism.

Generations of dentists were educated by this ideology in the prominent

textbook on occlusion of the time, however therapy centered around

removal of occlusal interference remained unsatisfactory. The belief

among dentists that occlusion and bruxism are strongly related is still

widespread, however the majority of researchers now disfavor

malocclusion as the main etiologic factor in favor of a more

multifactorial, biopsychosocial model of bruxism.

Society and culture

Clenching

the teeth is generally displayed by humans and other animals as a

display of anger, hostility or frustration. It is thought that in

humans, clenching the teeth may be an evolutionary instinct to display

teeth as weapons, thereby threatening a rival or a predator. The phrase

"to grit one's teeth" is the grinding or clenching of the teeth in

anger, or to accept a difficult or unpleasant situation and deal with it

in a determined way.

In the Bible there are several references to "gnashing of teeth" in both the Old Testament,

and the New Testament, where the phrase "wailing and gnashing of teeth"

describes what an imaginary king believes is occurring in the darkness

outside of his son's wedding venue.(Matthew 22:13)

In David Lynch's 1977 film Eraserhead,

Henry Spencer's partner ("Mary X") is shown tossing and turning in her

sleep, and snapping her jaws together violently and noisily, depicting

sleep bruxism. In Stephen King's 1988 novel "The Tommyknockers", the sister of central character Bobbi Anderson also had bruxism. In the 2000 film Requiem for a Dream, the character of Sara Goldfarb (Ellen Burstyn) begins taking an amphetamine-based diet pill and develops bruxism. In the 2005 film Beowulf & Grendel, a modern reworking of the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf,

Selma the witch tells Beowulf that the troll's name Grendel means

"grinder of teeth", stating that "he has bad dreams", a possible

allusion to Grendel traumatically witnessing the death of his father as a

child, at the hands of King Hrothgar. The Geats (the warriors who hunt

the troll) alternatively translate the name as "grinder of men's bones"

to demonize their prey. In George R. R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire series, King Stannis Baratheon grinds his teeth regularly, so loudly it can be heard "half a castle away".

In rave culture, recreational use of ecstasy

is often reported to cause bruxism. Among people who have taken

ecstasy, while dancing it is common to use pacifiers, lollipops or

chewing gum in an attempt to reduce the damage to the teeth and to

prevent jaw pain. Bruxism is thought to be one of the contributing factors in "meth mouth", a condition potentially associated with long term methamphetamine use.