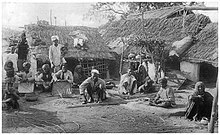

The Basor weaving bamboo baskets in a 1916 book. The Basor are a Scheduled Caste found in the state of Uttar Pradesh in India.

Caste is a form of social stratification characterized by endogamy,

hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an

occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social

interaction and exclusion based on cultural notions of purity and

pollution. Its paradigmatic ethnographic example is the division of India's Hindu society into rigid social groups, with roots in India's ancient history and persisting to the present time. However, the economic significance of the caste system in India

has been declining as a result of urbanization and affirmative action

programs. A subject of much scholarship by sociologists and

anthropologists, the Hindu caste system is sometimes used as an

analogical basis for the study of caste-like social divisions existing

outside Hinduism and India. The term "caste" is also applied to

morphological groupings in female populations of ants and bees.

Etymology

The English word "caste" derives from the Spanish and Portuguese casta, which, according to the John Minsheu's Spanish dictionary (1569), means "race, lineage, tribe or breed". When the Spanish colonized the New World, they used the word to mean a "clan or lineage". It was, however, the Portuguese who first employed casta

in the primary modern sense of the English word 'caste' when they

applied it to the thousands of endogamous, hereditary Indian social

groups they encountered upon their arrival in India in 1498. The use of the spelling "caste", with this latter meaning, is first attested in English in 1613.

Caste system in India

Modern India's caste system is based on the colonial superimposition

of the Portuguese word “casta” on the four-fold theoretical

classification called Varna and on natural social groupings called Jāti. From 1901 onwards, for the purposes of the Decennial Census, the British classified all Jātis into one or the other of the Varna

categories as described in ancient texts. Herbert Hope Risley, the

Census Commissioner, noted that "The principle suggested as a basis was

that of classification by social precedence as recognized by native

public opinion at the present day, and manifesting itself in the facts

that particular castes are supposed to be the modern representatives of

one or other of the castes of the theoretical Indian system."

Varna, as mentioned in ancient Hindu texts, describes society as divided into four categories: Brahmins (scholars and yajna priests), Kshatriyas (rulers and warriors), Vaishyas (farmers, merchants and artisans) and Shudras (workmen/service providers). The texts do not mention any hierarchy or a separate, untouchable category in Varna classification. Scholars believe that the Varnas

system was never truly operational in society and there is no evidence

of it ever being a reality in Indian history. The practical division of

the society had always been in terms of Jātis (birth groups),

which are not based on any specific religious principle, but could vary

from ethnic origins to occupations to geographic areas. The Jātis

have been endogamous social groups without any fixed hierarchy but

subject to vague notions of rank articulated over time based on

lifestyle and social, political or economic status. Many of India's

major empires and dynasties like the Mauryas, Shalivahanas, Chalukyas, Kakatiyas among many others, were founded by people who would have been classified as Shudras, under the Varnas

system. It is well established that by the 9th century, kings from all

the four Varnas, including Brahmins and Vaishyas, had occupied the

highest seat in the monarchical system in Hindu India, contrary to the

Varna theory.

In many instances, as in Bengal, historically the kings and rulers had

been called upon, when required, to mediate on the ranks of Jātis, which might number in thousands all over the subcontinent and vary by region. In practice, the jātis may or may not fit into the Varna classes and many prominent Jatis, for example the Jats and Yadavs, straddled two Varnas i.e. Kshatriyas and Vaishyas, and the Varna status of Jātis itself was subject to articulation over time.

Starting with the British colonial Census of 1901 led by Herbert Hope Risley, all the jātis were grouped under the theoretical varnas categories. According to political scientist Lloyd Rudolph, Risley believed that varna,

however ancient, could be applied to all the modern castes found in

India, and "[he] meant to identify and place several hundred million

Indians within it."

In an effort to arrange various castes in order of precedence

functional grouping was based less on the occupation that prevailed in

each case in the present day than on that which was traditional with it,

or which gave rise to its differentiation from the rest of the

community. "This action virtually removed Indians from the progress of

history and condemned them to an unchanging position and place in time.

In one sense, it is rather ironic that the British, who continually

accused the Indian people of having a static society, should then impose

a construct that denied progress" The terms varna (conceptual classification based on occupation) and jāti (groups) are two distinct concepts: while varna is a theoretical four-part division, jāti

(community) refers to the thousands of actual endogamous social groups

prevalent across the subcontinent. The classical authors scarcely speak

of anything other than the varnas, as it provided a convenient shorthand; but a problem arises when colonial Indologists sometimes confuse the two.

Thus, starting with the 1901 Census, caste officially became India's

essential institution, with an imprimatur from the British

administrators, augmenting a discourse that had already dominated

Indology. “Despite India's acquisition of formal political independence,

it has still not regained the power to know its own past and present

apart from that discourse”.

An image of a man and woman from the toddy-tapping community in Malabar from the manuscript Seventy-two Specimens of Castes in India,

which consists of 72 full-color hand-painted images of men and women of

various religions, occupations and ethnic groups found in Madura, India

in 1837, which confirms the popular perception and nature of caste as

Jati, before the British made it applicable only to Hindus grouped under

the varna categories from the 1901 census onwards.

Upon independence from Britain, the Indian Constitution listed 1,108

castes across the country as Scheduled Castes in 1950, for positive

discrimination. The Untouchable communities are sometimes called Scheduled Castes, Dalit or Harijan in contemporary literature. In 2001, Dalits were 16.2% of India's population. Most of the 15 million bonded child workers are from the lowest castes. Independent India has witnessed caste-related violence. In 2005, government recorded approximately 110,000 cases of reported violent acts, including rape and murder, against Dalits. For 2012, the government recorded 651 murders, 3,855 injuries, 1,576 rapes, 490 kidnappings, and 214 cases of arson.

The socio-economic limitations of the caste system are reduced due to urbanization and affirmative action. Nevertheless, the caste system still exists in endogamy and patrimony,

and thrives in the politics of democracy, where caste provides ready

made constituencies to politicians. The globalization and economic

opportunities from foreign businesses has influenced the growth of

India's middle-class population. Some members of the Chhattisgarh Potter

Caste Community (CPCC) are middle-class urban professionals and no

longer potters unlike the remaining majority of traditional rural potter

members. There is persistence of caste in Indian politics. Caste

associations have evolved into caste-based political parties. Political

parties and the state perceive caste as an important factor for

mobilization of people and policy development.

Studies by Bhatt and Beteille have shown changes in status,

openness, mobility in the social aspects of Indian society. As a result

of modern socio-economic changes in the country, India is experiencing

significant changes in the dynamics And the economics of its social

sphere.

While arranged marriages are still the most common practice in India,

the internet has provided a network for younger Indians to take control

of their relationships through the use of dating apps. This remains

isolated to informal terms, as marriage is not often achieved through

the use of these apps.

Hypergamy is still a common practice in India and Hindu culture. Men

are expected to marry within their caste, or one below, with no social

repercussions. If a woman marries into a higher caste, then her children

will take the status of their father. If she marries down, her family

is reduced to the social status of their son in law. In this case, the

women are bearers of the egalitarian principle of the marriage. There

would be no benefit in marrying a higher caste if the terms of the

marriage did not imply equality. However, men are systematically shielded from the negative implications of the agreement.

Geographical factors also determine adherence to the caste

system. Many Northern villages are more likely to participate in

exogamous marriage, due to a lack of eligible suitors within the same

caste. Women in North India have been found to be less likely to leave

or divorce their husbands since they are of a relatively lower caste

system, and have higher restrictions on their freedoms. On the other

hand, Pahari women, of the northern mountains, have much more freedom to

leave their husbands without stigma. This often leads to better

husbandry as his actions are not protected by social expectations.

Chiefly among the factors influencing the rise of exogamy is the rapid urbanisation in India

experienced over the last century. It is well known that urban centers

tend to be less reliant on agriculture and are more progressive as a

whole. As India’s cities boomed in population, the job market grew to

keep pace. Prosperity and stability were now more easily attained by an

individual, and the anxiety to marry quickly and effectively was

reduced. Thus, younger, more progressive generations of urban Indians

are less likely than ever to participate in the antiquated system of

arranged endogamy.

India has also implemented a form of Affirmative Action, locally

known as “reservation groups”. Quota system jobs, as well as placements

in publicly funded colleges, hold spots for the 8% of India’s minority,

and underprivileged groups. As a result, in states such as Tamil Nadu or

those in the north-east, where underprivileged populations predominate,

over 80% of government jobs are set aside in quotas. In education,

colleges lower the marks necessary for the Dalits to enter.