| Pogrom | |

|---|---|

| |

| Target | Predominantly Jews |

A pogrom is a violent riot aimed at the massacre or expulsion of an ethnic or religious group, particularly one aimed at Jews. The Slavic-languages term originally entered the English language to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian Empire (mostly within the Pale of Settlement). Similar attacks against Jews at other times and places also became retrospectively known as pogroms. The word is now also sometimes used to describe publicly sanctioned purgative attacks against non-Jewish ethnic or religious groups. The characteristics of a pogrom vary widely, depending on the specific incidents, at times leading to, or culminating in, massacres.

Significant pogroms in the Russian Empire included the Odessa pogroms, Warsaw pogrom (1881), Kishinev pogrom (1903), Kiev Pogrom (1905), and Białystok pogrom (1906). After the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917, several pogroms occurred amid the power struggles in Eastern Europe, including the Lwów pogrom (1918) and Kiev Pogroms (1919).

The most significant pogrom in Nazi Germany was the Kristallnacht of 1938. At least 91 Jews were killed, a further thirty thousand arrested and subsequently incarcerated in concentration camps, a thousand synagogues burned, and over seven thousand Jewish businesses destroyed or damaged. Notorious pogroms of World War II included the 1941 Farhud in Iraq, the July 1941 Iaşi pogrom in Romania – in which over 13,200 Jews were killed – as well as the Jedwabne pogrom in German-occupied Poland. Post-World War II pogroms included the 1945 Tripoli pogrom, the 1946 Kielce pogrom and the 1947 Aleppo pogrom.

Etymology

First recorded in 1882, the Russian word pogrom (погро́м, pronounced [pɐˈgrom]) is derived from the common prefix po- (по-) and the verb gromit' (громи́ть, [grɐˈmʲitʲ]) meaning "to destroy, to wreak havoc, to demolish violently". The noun pogrom, which has a relatively short history, is used in English and many other languages as a loanword, possibly borrowed from Yiddish (where the word takes the form פאָגראָם). Its widespread circulation in today's world began with the antisemitic violence in the Russian Empire in 1881–1883.

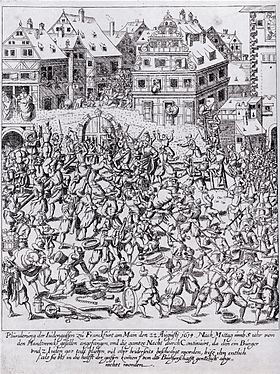

The Hep-Hep riots

in Frankfurt, 1819. On the left, two peasant women are assaulting a

Jewish man with pitchfork and broom. On the right, a man wearing

spectacles, tails and a six-button waistcoat, "perhaps a pharmacist or a

schoolteacher,"

holds a Jewish man by the throat and is about to club him with a

truncheon. The houses are being looted. A contemporary engraving by Johann Michael Voltz.

Historical background

The first recorded anti-Jewish riots took place in Alexandria in the year 38 CE, followed by the more known riot of 66 CE. Other notable events took place in Europe during the Middle Ages. Jewish communities were targeted in the Black Death Jewish persecutions of 1348–1350, in Toulon in 1348, the Massacre of 1391 in Barcelona as well as in other Catalan cities, during the Erfurt massacre (1349), the Basel massacre, massacres in Aragon and in Flanders, as well as the "Valentine's Day" Strasbourg pogrom of 1349. Some 510 Jewish communities were destroyed during this period, extending further to the Brussels massacre of 1370. On Holy Saturday of 1389, a pogrom began in Prague

that led to the burning of the Jewish quarter, the killing of many

Jews, and the suicide of many Jews trapped in the main synagogue; the

number of dead was estimated at 400–500 men, women and children.

The brutal murders of Jews and Poles occurred during the Khmelnytsky Uprising of 1648–1657 in present-day Ukraine. Modern historians give estimates of the scale of the murders by Khmelnytsky's Cossacks ranging between 40,000 and 100,000 men, women and children, or perhaps many more.

The outbreak of violence against Jews (Hep-Hep riots) occurred at the beginning of the 19th century as a reaction to Jewish emancipation in the German Confederation.

Russian Empire

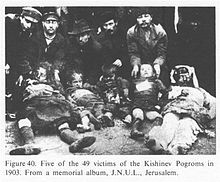

Victims of a pogrom in Kishinev, Bessarabia, 1903

The Russian Empire, which previously had very few Jews, acquired territories in the Russian Partition that contained a large Jewish populations, during the military partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793 and 1795. In conquered territories, a new political entity called the Pale of Settlement was formed in 1791 by Catherine the Great.

Most Jews from the former Commonwealth were allowed to reside only

within the Pale, including families expelled by royal decree from St.

Petersburg, Moscow and other large Russian cities. The 1821 Odessa pogroms marked the beginning of the 19th century pogroms in Tsarist Russia; there were four more such pogroms in Odessa before the end of the century. Following the assassination of Alexander II in 1881 by Narodnaya Volya

– blamed on the Jews by the Russian government, anti-Jewish events

turned into a wave of over 200 pogroms by their modern definition, which

lasted for several years. Jewish self-governing Kehillah were abolished by Tsar Nicholas I in 1844.

The first in 20th-century Russia was the Kishinev pogrom of 1903 in which 49 Jews were killed, hundreds wounded, 700 homes destroyed and 600 businesses pillaged. In the same year, pogroms took place in Gomel (Belarus), Smela, Feodosiya and Melitopol (Ukraine). Extreme savagery was typified by mutilations of the wounded. They were followed by the Zhitomir pogrom (with 29 killed), and the Kiev pogrom of October 1905 resulting in a massacre of approximately 100 Jews.

In three years between 1903 and 1906, about 660 pogroms were recorded

in Ukraine and Bessarabia; half a dozen more in Belorussia, carried out

with the Russian government's complicity, but no anti-Jewish pogroms

were recorded in Poland. At about that time, the Jewish Labor Bund began organizing armed self-defense units ready to shoot back, and the pogroms subsided for a number of years. According to professor Colin Tatz, between 1881 and 1920 there were 1,326 pogroms in Ukraine which took the lives of 70,000 to 250,000 civilian Jews, leaving half a million homeless.

Eastern Europe after World War I

Map of pogroms in Ukraine between 1918 and 1920 per casualties

Large-scale pogroms, which began in the Russian Empire several decades earlier, intensified during the period of the Russian Civil War in the aftermath of World War I. Professor Zvi Gitelman (A Century of Ambivalence)

estimated that only in 1918–1919 over 1,200 pogroms took place in

Ukraine, thus amounting to the greatest slaughter of Jews in Eastern

Europe since 1648.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in his book Two Hundred Years Together provided additional statistics from research conducted by Nahum Gergel

(1887–1931). Gergel counted 1,236 incidents of anti-Jewish violence and

estimated that 887 mass pogroms occurred, the remainder being

classified as "excesses" not assuming mass proportions. The Kiev pogroms of 1919,

according to Gitelman, were the first of a subsequent wave of pogroms

in which between 30,000 and 70,000 Jews were massacred across Ukraine. Of all the pogroms accounted for in Gergel's research:

- About 40 percent were perpetrated by the Ukrainian People's Republic forces led by Symon Petliura,

- The Republic issued orders condemning pogroms, but lacked authority to intervene. After May 1919 the Directory lost its role as a credible governing body; almost 75 percent of pogroms occurred between May and September of that year. Thousands of Jews were killed only for being Jewish, without any political affiliations.

- 25 percent by the Ukrainian Green Army and various Ukrainian nationalist gangs,

- 17 percent by the White Army, especially the forces of Anton Denikin,

- 8.5 percent of Gergel's total was attributed to pogroms carried out by men of the Red Army (more specifically Semyon Budenny's First Cavalry, most of whose soldiers had previously served under Denikin).

- These pogroms were not, however, sanctioned by the Bolshevik leadership; the high command "vigorously condemned these pogroms and disarmed the guilty regiments", and the pogroms would soon be condemned by Mikhail Kalinin in a speech made at a military parade in the Ukraine.

Gergel's overall figures, which are generally considered

conservative, are based on the testimony of witnesses and newspaper

reports collected by the Mizrakh-Yidish Historiche Arkhiv which

was first based in Kiev, then Berlin and later New York. The English

version of Gergel's article was published in 1951 in the YIVO Annual of Jewish Social Science titled "The Pogroms in the Ukraine in 1918–1921."

On 8 August 1919, during the Polish–Soviet War, Polish troops took over Minsk in Operation Minsk.

They killed 31 Jews merely suspected of supporting the Bolshevist

movement, beat and attacked many more, looted 377 Jewish-owned shops

(aided by the local civilians) and ransacked many private homes.

The "Morgenthau's report of October 1919 stated that there is no

question that some of the Jewish leaders exaggerated these evils."

According to Elissa Bemporad, the "violence endured by the Jewish

population under the Poles encouraged popular support for the Red Army,

as Jewish public opinion welcomed the establishment of the Belorussian SSR."

After the First World War, during the localized armed conflicts of independence, 72 Jews were killed and 443 injured in the 1918 Lwów pogrom. The following year, pogroms were reported by the New York Tribune in several cities in the newly established Second Polish Republic.

Rest of the world

In the early 20th century, pogroms broke out elsewhere in the world as well. In 1904 in Ireland, the Limerick boycott caused several Jewish families to leave the town. During the 1911 Tredegar riot in Wales, Jewish homes and businesses were looted and burned over the period of a week, before the British Army was called in by then-Home Secretary Winston Churchill, who described the riot as a "pogrom". In 1919 there was a pogrom in Argentina, during the Tragic Week.

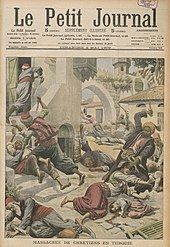

In the Mandatory Palestine under British administration, the Jews were targeted in the 1929 Hebron massacre and the 1929 Safed pogrom. In 1934 there were pogroms against Jews in Turkey and Algeria.

Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe

Iași pogrom in Romania, June 1941

The first pogrom in Nazi Germany was the Kristallnacht, often called Pogromnacht, in which at least 91 Jews were killed, a further 30,000 arrested and incarcerated in Nazi concentration camps, over 1,000 synagogues burned, and over 7,000 Jewish businesses destroyed or damaged.

During World War II, Nazi German death squads encouraged local populations in German-occupied Europe to commit pogroms against Jews. Brand new battalions of Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz (trained by SD agents) were mobilized from among the German minorities.

A large number of pogroms occurred during the Holocaust at the hands of non-Germans. Perhaps the deadliest of these Holocaust-era pogroms was the Iași pogrom in Romania, perpetrated by Ion Antonescu, in which as many as 13,266 Jews were killed by Romanian citizens, police and military officials.

On 1–2 June 1941, in the two-day Farhud pogrom in Iraq, perpetrated by Rashid Ali, Yunis al-Sabawi, and the al-Futuwa

youth, "rioters murdered between 150 and 180 Jews, injured 600 others,

and raped an undetermined number of women. They also looted some 1,500

stores and homes". Also 300-400 non-Jewish rioters were killed in the attempt to quell the violence.

Jewish woman chased by men and youth armed with clubs during the Lviv pogroms, July 1941

In June–July 1941, encouraged by the Einsatzgruppen in the city of Lviv the Ukrainian People's Militia perpetrated two citywide pogroms in which around 6,000 Polish Jews were murdered, in retribution for alleged collaboration with the Soviet NKVD. In Lithuania, some local police led by Algirdas Klimaitis and Lithuanian partisans – consisting of LAF units reinforced by 3,600 deserters from the 29th Lithuanian Territorial Corps of the Red Army promulgated anti-Jewish pogroms in Kaunas along with occupying Nazis. On 25–26 June 1941, about 3,800 Jews were killed and synagogues and Jewish settlements burned.

During the Jedwabne pogrom of July 1941, ethnic Poles burned at least 340 Jews in a barn (Institute of National Remembrance) in the presence of Nazi German Ordnungspolizei. The role of the German Einsatzgruppe B remains the subject of debate.

After World War II

After the end of World War II, a series of violent antisemitic incidents occurred against returning Jews throughout Europe, particularly in the Soviet-occupied East where Nazi propagandists had extensively promoted the notion of a Jewish-Communist conspiracy (see Anti-Jewish violence in Poland, 1944–1946 and Anti-Jewish violence in Eastern Europe, 1944–1946). Anti-Jewish riots also took place in Britain in 1947.

In the Arab world, anti-Jewish rioters killed over 140 Jews in the 1945 Anti-Jewish Riots in Tripolitania. Following the start of the 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine,

a number of anti-Jewish events occurred throughout the Arab world, some

of which have been described as pogroms. In 1947, half of Aleppo's

10,000 Jews left the city in the wake of the Aleppo riots, while other anti-Jewish riots took place in British Aden and the French Moroccan cities of Oujda and Jerada.

In 2020, a series of riots in North East Delhi in which Hindu nationalist mobs attacked Muslims and vandalized Muslim properties and mosques was widely described as a pogrom. During the riots, 53 people were killed and more than 350 were injured.

Usage

According to Encyclopædia Britannica, "the term is usually applied to attacks on Jews in the Russian Empire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, [and] the first extensive pogroms followed the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881", and the Wiley-Blackwell Dictionary of Modern European History Since 1789 states that pogroms "were antisemitic disturbances that periodically occurred within the tsarist empire." However, the term is widely used to refer to many events which occurred prior to the Anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire. Historian of Russian Jewry John Klier writes in Russians, Jews, and the Pogroms of 1881–1882

that "By the twentieth century, the word 'pogrom' had become a generic

term in English for all forms of collective violence directed against

Jews." Abramson wrote that "in mainstream usage the word has come to imply an act of antisemitism",

since while "Jews have not been the only group to suffer under this

phenomenon ... historically Jews have been frequent victims of such

violence".

The 1921 Tulsa race massacre, which destroyed the wealthiest black community in the United States, has been described as a pogrom.

The term is also used in reference to attacks on non-Jewish ethnic minorities, and accordingly some scholars do not include antisemitism as the defining characteristic of pogroms. Reviewing its uses in scholarly literature, historian Werner Bergmann proposes that pogroms should be "defined as a unilateral, nongovernmental form of collective violence that is initiated by the majority population against a largely defenseless ethnic group, and he also states that pogroms occur when the majority expects the state to provide it with no assistance in overcoming a (perceived) threat from the minority," but he adds that in Western usage, the word's "anti-Semitic overtones" have been retained. Historian David Engel

supports this, writing that "there can be no logically or empirically

compelling grounds for declaring that some particular episode does or

does not merit the label [pogrom]," but states that the majority of the

incidents "habitually" described as pogroms took place in societies that

were significantly divided by ethnicity and/or religion

where the violence was committed by members of the higher-ranking group

against members of a stereotyped lower-ranking group with which they

expressed some complaint, and the members of the higher-ranking group

justified their acts of violence by claiming that the law of the land

would not be used to stop them.

There is no universally accepted set of characteristics which define the term pogrom. Klier writes that "when applied indiscriminately to events in Eastern Europe,

the term can be misleading, the more so when it implies that 'pogroms'

were regular events in the region and that they always shared common

features." Use of the term pogrom to refer to events in 1918–19 in Polish cities including Kielce pogrom, Pinsk massacre and Lwów pogrom, was specifically avoided in the 1919 Morgenthau Report

and the word "excesses" was used instead because the authors argued

that the use of the term "pogrom" required a situation to be antisemitic rather than political in nature, which meant that it was inapplicable to the conditions existing in a war zone, and media use of the term pogrom to refer to the 1991 Crown Heights riot caused public controversy. In 2008, two separate attacks in the West Bank by Israeli Jewish settlers on Palestinian Arabs were characterized as pogroms by then Prime Minister of Israel Ehud Olmert.

Werner Bergmann suggests that all such incidents have a particularly unifying characteristic: "[b]y the collective attribution of a threat, the pogrom differs from other forms of violence, such as lynchings, which are directed at individual members of a minority group, while the imbalance of power in favor of the rioters distinguishes pogroms from other forms of riots (food riots, race riots or 'communal riots' between evenly matched groups); and again, the low level of organization separates them from vigilantism, terrorism, massacre and genocide".