A satellite or an artificial satellite is an object, typically a spacecraft, placed into orbit around a celestial body. They have a variety of uses, including communication relay, weather forecasting, navigation (GPS), broadcasting, scientific research, and Earth observation. Additional military uses are reconnaissance, early warning, signals intelligence and, potentially, weapon delivery. Other satellites include the final rocket stages that place satellites in orbit and formerly useful satellites that later become defunct.

Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs). Most satellites also have a method of communication to ground stations, called transponders. Many satellites use a standardized bus to save cost and work, the most popular of which are small CubeSats. Similar satellites can work together as groups, forming constellations. Because of the high launch cost to space, most satellites are designed to be as lightweight and robust as possible. Most communication satellites are radio relay stations in orbit and carry dozens of transponders, each with a bandwidth of tens of megahertz.

Spaceships become satellites by accelerating or decelerating to reach orbital velocities, occupying an orbit high enough to avoid orbital decay due to drag in the presence of an atmosphere and above their Roche limit. Satellites are spacecraft launched from the surface into space by launch systems. Satellites can then change or maintain their orbit by propulsion, usually by chemical or ion thrusters. As of 2018, about 90% of the satellites orbiting the Earth are in low Earth orbit or geostationary orbit; geostationary means the satellites stay still in the sky (relative to a fixed point on the ground). Some imaging satellites choose a Sun-synchronous orbit because they can scan the entire globe with similar lighting. As the number of satellites and amount of space debris around Earth increases, the threat of collision has become more severe. An orbiter is a spacecraft that is designed to perform an orbital insertion, entering orbit around an astronomical body from another, and as such becoming an artificial satellite. A small number of satellites orbit other bodies (such as the Moon, Mars, and the Sun) or many bodies at once (two for a halo orbit, three for a Lissajous orbit).

Earth observation satellites gather information for reconnaissance, mapping, monitoring the weather, ocean, forest, etc. Space telescopes take advantage of outer space's near perfect vacuum to observe objects with the entire electromagnetic spectrum. Because satellites can see a large portion of the Earth at once, communications satellites can relay information to remote places. The signal delay from satellites and their orbit's predictability are used in satellite navigation systems, such as GPS. Crewed spacecrafts which are in orbit or remain in orbit, like Space stations, are artificial satellites as well.

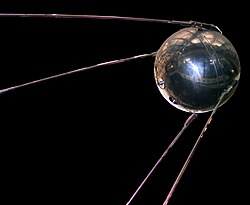

The first artificial satellite launched into the Earth's orbit was the Soviet Union's Sputnik 1, on October 4, 1957. As of December 31, 2022, there are 6,718 operational satellites in the Earth's orbit, of which 4,529 belong to the United States (3,996 commercial), 590 belong to China, 174 belong to Russia, and 1,425 belong to other nations.[2]

History

Early proposals

The first published mathematical study of the possibility of an artificial satellite was Newton's cannonball, a thought experiment by Isaac Newton to explain the motion of natural satellites, in his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687). The first fictional depiction of a satellite being launched into orbit was a short story by Edward Everett Hale, "The Brick Moon" (1869). The idea surfaced again in Jules Verne's The Begum's Fortune (1879).

In 1903, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857–1935) published Exploring Space Using Jet Propulsion Devices, which was the first academic treatise on the use of rocketry to launch spacecraft. He calculated the orbital speed required for a minimal orbit, and inferred that a multi-stage rocket fueled by liquid propellants could achieve this.

Herman Potočnik explored the idea of using orbiting spacecraft for detailed peaceful and military observation of the ground in his 1928 book, The Problem of Space Travel. He described how the special conditions of space could be useful for scientific experiments. The book described geostationary satellites (first put forward by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky) and discussed the communication between them and the ground using radio, but fell short with the idea of using satellites for mass broadcasting and as telecommunications relays.

In a 1945 Wireless World article, English science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke described in detail the possible use of communications satellites for mass communications. He suggested that three geostationary satellites would provide coverage over the entire planet.

In May 1946, the United States Air Force's Project RAND released the Preliminary Design of an Experimental World-Circling Spaceship, which stated "A satellite vehicle with appropriate instrumentation can be expected to be one of the most potent scientific tools of the Twentieth Century." The United States had been considering launching orbital satellites since 1945 under the Bureau of Aeronautics of the United States Navy. Project RAND eventually released the report, but considered the satellite to be a tool for science, politics, and propaganda, rather than a potential military weapon.

In 1946, American theoretical astrophysicist Lyman Spitzer proposed an orbiting space telescope.

In February 1954, Project RAND released "Scientific Uses for a Satellite Vehicle", by R. R. Carhart. This expanded on potential scientific uses for satellite vehicles and was followed in June 1955 with "The Scientific Use of an Artificial Satellite", by H. K. Kallmann and W. W. Kellogg.

First satellites

The first artificial satellite was Sputnik 1, launched by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 under the Sputnik program, with Sergei Korolev as chief designer. Sputnik 1 helped to identify the density of high atmospheric layers through measurement of its orbital change and provided data on radio-signal distribution in the ionosphere. The unanticipated announcement of Sputnik 1's success precipitated the Sputnik crisis in the United States and ignited the so-called Space Race within the Cold War.

In the context of activities planned for the International Geophysical Year (1957–1958), the White House announced on 29 July 1955 that the U.S. intended to launch satellites by the spring of 1958. This became known as Project Vanguard. On 31 July, the Soviet Union announced its intention to launch a satellite by the fall of 1957.

Sputnik 2 was launched on 3 November 1957 and carried the first living passenger into orbit, a dog named Laika. The dog was sent without possibility of return.

In early 1955, after being pressured by the American Rocket Society, the National Science Foundation, and the International Geophysical Year, the Army and Navy worked on Project Orbiter with two competing programs. The army used the Jupiter C rocket, while the civilian–Navy program used the Vanguard rocket to launch a satellite. Explorer 1 became the United States' first artificial satellite, on 31 January 1958. The information sent back from its radiation detector led to the discovery of the Earth's Van Allen radiation belts. The TIROS-1 spacecraft, launched on April 1, 1960, as part of NASA's Television Infrared Observation Satellite (TIROS) program, sent back the first television footage of weather patterns to be taken from space.

In June 1961, three and a half years after the launch of Sputnik 1, the United States Space Surveillance Network cataloged 115 Earth-orbiting satellites.

While Canada was the third country to build a satellite which was launched into space, it was launched aboard an American rocket from an American spaceport. The same goes for Australia, whose launch of the first satellite involved a donated U.S. Redstone rocket and American support staff as well as a joint launch facility with the United Kingdom. The first Italian satellite San Marco 1 was launched on 15 December 1964 on a U.S. Scout rocket from Wallops Island (Virginia, United States) with an Italian launch team trained by NASA. In similar occasions, almost all further first national satellites were launched by foreign rockets.

France was the third country to launch a satellite on its own rocket. On 26 November 1965, the Astérix or A-1 (initially conceptualized as FR.2 or FR-2), was put into orbit by a Diamant A rocket launched from the CIEES site at Hammaguir, Algeria. With Astérix, France became the sixth country to have an artificial satellite.

Later Satellite Development

Early satellites were built to unique designs. With advancements in technology, multiple satellites began to be built on single model platforms called satellite buses. The first standardized satellite bus design was the HS-333 geosynchronous (GEO) communication satellite launched in 1972. Beginning in 1997, FreeFlyer is a commercial off-the-shelf software application for satellite mission analysis, design, and operations.

After the late 2010s, and especially after the advent and operational fielding of large satellite internet constellations—where on-orbit active satellites more than doubled over a period of five years—the companies building the constellations began to propose regular planned deorbiting of the older satellites that reached the end of life, as a part of the regulatory process of obtaining a launch license. The largest artificial satellite ever is the International Space Station.

By the early 2000s, and particularly after the advent of CubeSats and increased launches of microsats—frequently launched to the lower altitudes of low Earth orbit (LEO)—satellites began to more frequently be designed to get destroyed, or breakup and burnup entirely in the atmosphere. For example, SpaceX Starlink satellites, the first large satellite internet constellation to exceed 1000 active satellites on orbit in 2020, are designed to be 100% demisable and burn up completely on their atmospheric reentry at the end of their life, or in the event of an early satellite failure.

In different periods, many countries, such as Algeria, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Denmark, Egypt, Finland, France, Germany, India, Iran, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, South Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, Pakistan, Poland, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, the United Kingdom and the United States, had some satellites in orbit.

Japan's space agency (JAXA) and NASA plan to send a wooden satellite prototype called LingoSat into orbit in the summer of 2024. They have been working on this project for few years and sent first wood samples to the space in 2021 to test the material's resilience to space conditions.

Components

Orbit and altitude control

Most satellites use chemical or ion propulsion to adjust or maintain their orbit, coupled with reaction wheels to control their three axis of rotation or attitude. Satellites close to Earth are affected the most by variations in the Earth's magnetic, gravitational field and the Sun's radiation pressure; satellites that are further away are affected more by other bodies' gravitational field by the Moon and the Sun. Satellites utilize ultra-white reflective coatings to prevent damage from UV radiation. Without orbit and orientation control, satellites in orbit will not be able to communicate with ground stations on the Earth.

Chemical thrusters on satellites usually use monopropellant (one-part) or bipropellant (two-parts) that are hypergolic. Hypergolic means able to combust spontaneously when in contact with each other or to a catalyst. The most commonly used propellant mixtures on satellites are hydrazine-based monopropellants or monomethylhydrazine–dinitrogen tetroxide bipropellants. Ion thrusters on satellites usually are Hall-effect thrusters, which generate thrust by accelerating positive ions through a negatively-charged grid. Ion propulsion is more efficient propellant-wise than chemical propulsion but its thrust is very small (around 0.5 N or 0.1 lbf), and thus requires a longer burn time. The thrusters usually use xenon because it is inert, can be easily ionized, has a high atomic mass and storable as a high-pressure liquid.

Power

Most satellites use solar panels to generate power, and a few in deep space with limited sunlight use radioisotope thermoelectric generators. Slip rings attach solar panels to the satellite; the slip rings can rotate to be perpendicular with the sunlight and generate the most power. All satellites with a solar panel must also have batteries, because sunlight is blocked inside the launch vehicle and at night. The most common types of batteries for satellites are lithium-ion, and in the past nickel–hydrogen.

Applications

Earth observation

Earth observation satellites are designed to monitor and survey the Earth, called remote sensing. Most Earth observation satellites are placed in low Earth orbit for a high data resolution, though some are placed in a geostationary orbit for an uninterrupted coverage. Some satellites are placed in a Sun-synchronous orbit to have consistent lighting and obtain a total view of the Earth. Depending on the satellites' functions, they might have a normal camera, radar, lidar, photometer, or atmospheric instruments. Earth observation satellite's data is most used in archaeology, cartography, environmental monitoring, meteorology, and reconnaissance applications. As of 2021, there are over 950 Earth observation satellites, with the largest number of satellites operated with Planet Labs.

Weather satellites monitor clouds, city lights, fires, effects of pollution, auroras, sand and dust storms, snow cover, ice mapping, boundaries of ocean currents, energy flows, etc. Environmental monitoring satellites can detect changes in the Earth's vegetation, atmospheric trace gas content, sea state, ocean color, and ice fields. By monitoring vegetation changes over time, droughts can be monitored by comparing the current vegetation state to its long term average. Anthropogenic emissions can be monitored by evaluating data of tropospheric NO2 and SO2.

Communication

A communications satellite is an artificial satellite that relays and amplifies radio telecommunication signals via a transponder; it creates a communication channel between a source transmitter and a receiver at different locations on Earth. Communications satellites are used for television, telephone, radio, internet, and military applications. Some communications satellites are in geostationary orbit 22,236 miles (35,785 km) above the equator, so that the satellite appears stationary at the same point in the sky; therefore the satellite dish antennas of ground stations can be aimed permanently at that spot and do not have to move to track the satellite. But most form satellite constellations in low Earth orbit, where antennas on the ground have to follow the position of the satellites and switch between satellites frequently.

The radio waves used for telecommunications links travel by line of sight and so are obstructed by the curve of the Earth. The purpose of communications satellites is to relay the signal around the curve of the Earth allowing communication between widely separated geographical points. Communications satellites use a wide range of radio and microwave frequencies. To avoid signal interference, international organizations have regulations for which frequency ranges or "bands" certain organizations are allowed to use. This allocation of bands minimizes the risk of signal interference.Spy satellites

When an Earth observation satellite or a communications satellite is deployed for military or intelligence purposes, it is known as a spy satellite or reconnaissance satellite.

Their uses include early missile warning, nuclear explosion detection, electronic reconnaissance, and optical or radar imaging surveillance.

Navigation

Navigational satellites are satellites that use radio time signals transmitted to enable mobile receivers on the ground to determine their exact location. The relatively clear line of sight between the satellites and receivers on the ground, combined with ever-improving electronics, allows satellite navigation systems to measure location to accuracies on the order of a few meters in real time.

Telescope

Astronomical satellites are satellites used for observation of distant planets, galaxies, and other outer space objects.

Experimental

Tether satellites are satellites that are connected to another satellite by a thin cable called a tether. Recovery satellites are satellites that provide a recovery of reconnaissance, biological, space-production and other payloads from orbit to Earth. Biosatellites are satellites designed to carry living organisms, generally for scientific experimentation. Space-based solar power satellites are proposed satellites that would collect energy from sunlight and transmit it for use on Earth or other places.

Weapon

Since the mid-2000s, satellites have been hacked by militant organizations to broadcast propaganda and to pilfer classified information from military communication networks. For testing purposes, satellites in low earth orbit have been destroyed by ballistic missiles launched from the Earth. Russia, United States, China and India have demonstrated the ability to eliminate satellites. In 2007, the Chinese military shot down an aging weather satellite, followed by the US Navy shooting down a defunct spy satellite in February 2008. On 18 November 2015, after two failed attempts, Russia successfully carried out a flight test of an anti-satellite missile known as Nudol. On 27 March 2019, India shot down a live test satellite at 300 km altitude in 3 minutes, becoming the fourth country to have the capability to destroy live satellites.

Environmental impact

The environmental impact of satellites is not currently well understood as they were previously assumed to be benign due to the rarity of satellite launches. However, the exponential increase and projected growth of satellite launches are bringing the issue into consideration. The main issues are resource use and the release of pollutants into the atmosphere which can happen at different stages of a satellite's lifetime.

Resource use

Resource use is difficult to monitor and quantify for satellites and launch vehicles due to their commercially sensitive nature. However, aluminium is a preferred metal in satellite construction due to its lightweight and relative cheapness and typically constitutes around 40% of a satellite's mass. Through mining and refining, aluminium has numerous negative environmental impacts and is one of the most carbon-intensive metals. Satellite manufacturing also requires rare elements such as lithium, gold, and gallium, some of which have significant environmental consequences linked to their mining and processing and/or are in limited supply. Launch vehicles require larger amounts of raw materials to manufacture and the booster stages are usually dropped into the ocean after fuel exhaustion. They are not normally recovered. Two empty boosters used for Ariane 5, which were composed mainly of steel, weighed around 38 tons each, to give an idea of the quantity of materials that are often left in the ocean.

Launches

Rocket launches release numerous pollutants into every layer of the atmosphere, especially affecting the atmosphere above the tropopause where the byproducts of combustion can reside for extended periods. These pollutants can include black carbon, CO2, nitrogen oxides (NOx), aluminium and water vapour, but the mix of pollutants is dependent on rocket design and fuel type. The amount of green house gases emitted by rockets is considered trivial as it contributes significantly less, around 0.01%, than the aviation industry yearly which itself accounts for 2-3% of the total global greenhouse gas emissions.

Rocket emissions in the stratosphere and their effects are only beginning to be studied and it is likely that the impacts will be more critical than emissions in the troposphere. The stratosphere includes the ozone layer and pollutants emitted from rockets can contribute to ozone depletion in a number of ways. Radicals such as NOx, HOx, and ClOx deplete stratospheric O3 through intermolecular reactions and can have huge impacts in trace amounts. However, it is currently understood that launch rates would need to increase by ten times to match the impact of regulated ozone-depleting substances. Whilst emissions of water vapour are largely deemed as inert, H2O is the source gas for HOx and can also contribute to ozone loss through the formation of ice particles. Black carbon particles emitted by rockets can absorb solar radiation in the stratosphere and cause warming in the surrounding air which can then impact the circulatory dynamics of the stratosphere. Both warming and changes in circulation can then cause depletion of the ozone layer.

Operational

Low earth orbit satellites

Several pollutants are released in the upper atmospheric layers during the orbital lifetime of LEO satellites. Orbital decay is caused by atmospheric drag and to keep the satellite in the correct orbit the platform occasionally needs repositioning. To do this nozzle-based systems use a chemical propellant to create thrust. In most cases hydrazine is the chemical propellant used which then releases ammonia, hydrogen and nitrogen as gas into the upper atmosphere. Also, the environment of the outer atmosphere causes the degradation of exterior materials. The atomic oxygen in the upper atmosphere oxidises hydrocarbon-based polymers like Kapton, Teflon and Mylar that are used to insulate and protect the satellite which then emits gasses like CO2 and CO into the atmosphere.

Night sky

Given the current surge in satellites in the sky, soon hundreds of satellites may be clearly visible to the human eye at dark sites. It is estimated that the overall levels of diffuse brightness of the night skies has increased by up to 10% above natural levels. This has the potential to confuse organisms, like insects and night-migrating birds, that use celestial patterns for migration and orientation. The impact this might have is currently unclear. The visibility of man-made objects in the night sky may also impact people's linkages with the world, nature, and culture.

Ground-based infrastructure

At all points of a satellite's lifetime, its movement and processes are monitored on the ground through a network of facilities. The environmental cost of the infrastructure as well as day-to-day operations is likely to be quite high, but quantification requires further investigation.

Degeneration

Particular threats arise from uncontrolled de-orbit.

Some notable satellite failures that polluted and dispersed radioactive materials are Kosmos 954, Kosmos 1402 and the Transit 5-BN-3.

When in a controlled manner satellites reach the end of life they are intentionally deorbited or moved to a graveyard orbit further away from Earth in order to reduce space debris. Physical collection or removal is not economical or even currently possible. Moving satellites out to a graveyard orbit is also unsustainable because they remain there for hundreds of years. It will lead to the further pollution of space and future issues with space debris. When satellites deorbit much of it is destroyed during re-entry into the atmosphere due to the heat. This introduces more material and pollutants into the atmosphere. There have been concerns expressed about the potential damage to the ozone layer and the possibility of increasing the earth's albedo, reducing warming but also resulting in accidental geoengineering of the earth's climate. After deorbiting 70% of satellites end up in the ocean and are rarely recovered.

Mitigation

Using wood as an alternative material has been posited in order to reduce pollution and debris from satellites that reenter the atmosphere.

Interference

Collision threat

Space debris pose dangers to the spacecraft (including satellites) in or crossing geocentric orbits and have the potential to drive a Kessler syndrome which could potentially curtail humanity from conducting space endeavors in the future.

With increase in the number of satellite constellations, like SpaceX Starlink, the astronomical community, such as the IAU, report that orbital pollution is getting increased significantly. A report from the SATCON1 workshop in 2020 concluded that the effects of large satellite constellations can severely affect some astronomical research efforts and lists six ways to mitigate harm to astronomy. The IAU is establishing a center (CPS) to coordinate or aggregate measures to mitigate such detrimental effects.

Radio interference

Due to the low received signal strength of satellite transmissions, they are prone to jamming by land-based transmitters. Such jamming is limited to the geographical area within the transmitter's range. GPS satellites are potential targets for jamming, but satellite phone and television signals have also been subjected to jamming.

Also, it is very easy to transmit a carrier radio signal to a geostationary satellite and thus interfere with the legitimate uses of the satellite's transponder. It is common for Earth stations to transmit at the wrong time or on the wrong frequency in commercial satellite space, and dual-illuminate the transponder, rendering the frequency unusable. Satellite operators now have sophisticated monitoring tools and methods that enable them to pinpoint the source of any carrier and manage the transponder space effectively.

Regulation

Issues like space debris, radio and light pollution are increasing in magnitude and at the same time lack progress in national or international regulation.

Liability

Generally liability has been covered by the Liability Convention.

Operation

The operation capabilities and use have very much diversified and is broadening increasingly.

Satellite operation needs not only access to financial, manufacturing and launch capabilities, but also a ground segment infrastructure.