The article describes cases in which scholars, politicians and journalists have described present or past denial of atrocity crimes against Indigenous nations. This denial may be the result of minority status, cultural distance, small scale or visibility, marginalization, the lack of political, economic and social status of Indigenous nations within a modern nation-state. This article will describe denial positions and related views on the subject.

The term atrocity crimes refers to three legally defined international crimes. According to the United Nations, these are genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. Some international organizations include ethnic cleansing as the fourth atrocity crime.

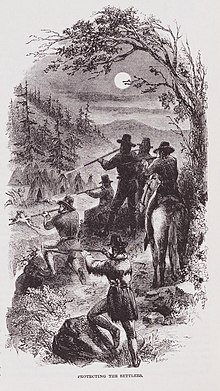

During the age of colonization, several states colonized territories which were inhabited by Indigenous peoples, and in some cases, they created new states that included the surviving Indigenous peoples within their new borders. In such processes of expanding their frontier, there were a number of cases of alleged atrocity crimes against Indigenous nations. Given that the dominant or majority group have held political and economic power, they have not addressed these issues on some occasions. In recent years, research by scholars and historians have increasingly examined the impact of settler colonialism and internal colonialism in general from the perspective of Indigenous peoples. The forced population and territorial controls of Indigenous peoples may include internal displacement, forced containment in reservations, forced assimilation and criminalization.

Background

In comparison with the legal definition of genocide in the Genocide Convention, other scholarly definitions have been used. For example, genocide scholar Israel Charny has proposed a definition of genocide: “Genocide in the generic sense is the mass killing of substantial numbers of human beings, when not in the course of military action against the military forces of an avowed enemy, under conditions of the essential defenselessness and helplessness of the victims.”

According to Gregory Stanton, founder of Genocide Watch, who wrote about the ten stages of genocide, the final stage of a genocide process is denial. In this stage, the perpetrators minimize, negate, lie and/or conceal information about events. Victims are blamed and deaths are attributed to side factors such as disease or starvation. Ward Churchill explains denial of genocide in terms of the politics of genocide recognition. Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky have argued that the attention given to issues is the product of mass media, as they mention in Manufacturing Consent: “A propaganda system will consistently portray people abused in enemy states as worthy victims, whereas those treated with equal or greater severity by its own government or clients will be unworthy!"[22] Thus, Chomsky views the term genocide as one that is used by those in positions of political power and media prominence against their rivals, but the avoidance of using the term to describe their own actions, past and present.[23]

Human rights and genocide are issues of international concern as the alleged perpetrators can be state agents themselves, while some states argue that internal matters are an issue of sovereignty. Unfortunately, many states do not respect the rights or even the lives of Indigenous peoples which exist within their political borders. These border themselves do not predate the territories of Indigenous peoples and may be the result of a settler or exploitation colonization process. For example, Britain and France traced close to 40% of the entire length of today's international boundaries. In the latter part of the twentieth century the genocide of Indigenous peoples attracted more attention from the international community including scholars and human rights organizations.

Indigenous peoples (also known as First peoples, First nations, Aboriginal peoples, Native peoples, Indigenous Natives, or Autochthonous peoples) are the earliest known inhabitants of a territory, especially a territory that has been colonized by a now-dominant group.

Significant governments and organizations

Often times, as evidence is presented of alleged past atrocity crimes, the governments have apologized or expressed regret, sometimes on behalf of the state for policies of previous governments. This has been the case for example in Australia, Belgium, Britain, Canada, California, Chile, El Salvador, Germany, Guatemala, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, and United States. In their apologies, state officials sometimes seem to disagree with the characterization or name of the crimes as described my human rights organizations and scholars.

Pope Francis apologized for the role of the Catholic Church during the colonization process "...for crimes committed against the native peoples during the so-called conquest of America". He has also apologized for the Catholic Church's role in the operation of residential schools in Canada, qualifying it as genocide.

In 2022 Justin Welby, the Primate of the Church of England, apologized to the Indigenous peoples of Canada, adding to similar apologies by other churches in Canada such as the Anglican Church of Canada.

Blaming the victims

As per Gregory Stanton, in the last stage of genocide, victims may be blamed for what happened to them. In the fourth phase, they can be dehumanized with hate speech.

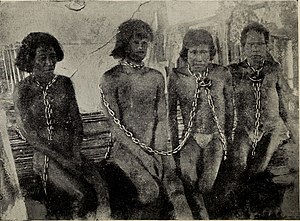

Often times, Indigenous peoples have been described with accounts of generalized practices like cannibalism. Historian David Stannard writes: "...the conquering Europeans were purposefully and systematically dehumanizing the people they were exterminating". Indigenous peoples have been dehumanized in accounts of Western scholars such as Juan Gines de Sepulveda to justify their slavery, oppression and even extermination. Controversial accounts of these peoples circulated in Europe in translations of letters by Christopher Columbus. Sepulveda used references to the Bible and Aristotle to depict Native Americans as natural slaves.

Australian professor Henry Reynolds says that many genocide scholars have named Tasmania in their lists of legitimate case studies:

This is equally true of genocide-in two ways. For all individual German to kill a Jew or a Gypsy, just because of the race of the victim, is an act of genocide. But to accuse the machinery of State under which such killings took place as an act of policy requires proof that this is their aim. There is ample proof that this was the aim of the "Final Solution". Jews were to be killed because they were not human, just as the Tasmanian Aborigines were hunted to death for the same reason.

Denial examples

In Canada, Justice Beverly McLachlin, of the Supreme Court, said that Canada's historical treatment of Indigenous peoples was cultural genocide. Professor David Bruce MacDonald argued that the Canadian government should recognize various atrocities committed against the Indigenous peoples in Canada. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau apologized in the context of the 2021 Canadian Indian residential schools gravesite discoveries. Tricia E. Logan writes that Canada has been in denial:

Canada, a country with oft-recounted histories of Indigenous origins and colonial legacies, still maintains a memory block in terms of the atrocities it committed to build the Canadian state. There is nothing more comforting in a colonial history of nation building than an erasure or denial of the true costs of colonial gains. The comforting narrative becomes the dominant and publicly consumed narrative.

David Stannard wrote on the 500 anniversary (1492) of the beginning of colonization of the Americas about denial of atrocities: "Expressions of horror and condemnation over ethnic cleansing in Bosnia and Herzegovina routinely appear on the same newspaper page or television news show as reports of the latest festivities surrounding the Columbian quincentennial. Bosnians and Croatians are worthy victims. The native peoples of the Americas never have been. But of late, American and European denials of culpability for the most thoroughgoing genocide in the history of the world have assumed a new guise." Stannard also interpreted an essay by author Christopher Hitchens, saying that Hitchens was supporting Social Darwinism:

To Hitchens, anyone who refused to join him in celebrating with "great vim and gusto" the annihilation of the native peoples of the Americas was (in his words) self-hating, ridiculous, ignorant, and sinister. People who regard critically the genocide that was carried out in America's past, Hitchens continued, are simply reactionary, since such grossly inhuman atrocities "happen to be the way history is made." And thus "to complain about them is as empty as complaint about climatic, geological or tectonic shift." Moreover, he added, such violence is worth glorifying since it more often than not has been for the long-term betterment of humankind, as in the United States today, where the extermination of the [Native Americans] has brought about "a nearly boundless epoch of opportunity and innovation."

Stannard offers the hypothetical scenario of 1940s Germans making similar statements if they had talked in such a way about Jews after World War II (as Hitchens and others talk about Native Americans) to compare the preponderance of the Holocaust vis-a-vis Native American genocide. Stannard in his essay concludes that the Holocaust has gained a prominent position in the public eye, gathering the attention of the international community, but even though he recognizes the scale and tragedy of the atrocity, he warns the West to not ignore the atrocities in the Western hemisphere:

...and so all people of conscience must be on guard against Holocaust deniers who, in many cases, would like nothing better than to see mass violence against Jews start again. By that same token, however, as we consider the terrible history and the ongoing campaigns of genocide against the indigenous inhabitants of the Western Hemisphere...

According to the New York Times, Lynne V. Cheney, former chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities, and a group of scholars had a dispute over Mrs. Cheney's rejection of a television project celebrating the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's discovery of the New World. Mrs. Cheney said the proposal's use of the word "genocide" in connection with Columbus was a problem: "We might be interested in funding a film that debated that issue," she said, "but we are not about to fund a film that asserts it. Columbus was guilty of many sins, but he was not Hitler."

In Australia, the Bringing Them Home report highlighted the abuse committed against Australian Indigenous peoples by forceful removal of children from Indigenous families. Nonetheless, former Prime Minister John Howard refused to apologize in the Motion of Reconciliation. The near-destruction of Tasmania's Aboriginal population has been described as an act of genocide by historians including, Mohamed Adhikari, Benjamin Madley, and Ashley Riley Sousa. In Australia there are ongoing debates about the interpretation of history, for example, the calling of Australia's national myth as an invasion or settlement.

In Britain, the Foreign Office concealed historical records that should been part of the public domain, related to the Mau Mau rebellion.

In Belgium, the atrocities in the Congo Free State are not recognized in the mainstream public discourse.

Some scholars describe Russia as a settler colonial state, particularly in its expansion into Siberia and the Russian Far East, during which it displaced and resettled Indigenous peoples, while practicing settler colonialism. The annexation of Siberia and the Far East to Russia was resisted by the indigenous peoples, while the Cossacks often committed atrocities against the indigenous peoples. During the Cold War, new forms of Indigenous repression were practiced.

In Paraguay and Brazil, there have been allegations of genocide denial of guilt as per genocide scholar Leo Kuper:

In contemporary extra-judicial discussions of allegations of genocide, the question of intent has become a controversial issue, providing a ready basis for denial of guilt.

Leo Kuper has described denial as a routine defense: "One of the consequences of the adoption of the Genocide Convention is that denial has become a routine defense. This is intimately related to its present recognition as an international crime with potentially significant sanctions by way of punishment, claims for reparation, and restitution of territorial rights....Denial by the oblivion of indifference has also been the fate of many hunting and gathering groups and other indigenous peoples."

Reactions to denial

Many countries in Europe have laws against Holocaust denial but currently, there are no known laws against Indigenous genocide denial. In Canada, some lawmakers want to criminalize the denial of genocide in residential schools: "They say they're being flooded with emails, letters and phone calls from people pushing back against the reports of suspected graves and skewing the history of the government-funded, church-run institutions that worked to assimilate more than 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children for more than a century."

Scholars

According to historian Howard Zinn, in American history textbooks, America's history of abuse against Indigenous peoples is mostly ignored, or presented from the point of view of the state. Academic Susan Cameron writes "Today, textbooks throughout the country continue to ignore or minimize the brutal treatment of Native peoples, the mass killings and persecutions, the displacement, and the continued struggles in tribal communities". Author Clifford Trafzer says that in public schools in California textbooks do not cover the California genocide.

David Moshman, a Professor at University of Nebraska–Lincoln, highlighted the fact that Indigenous nations are not a monolithic entity, and many have disappeared:

The nations of the Americas remain virtually oblivious to their emergence from a series of genocides that were deliberately aimed at, and succeeded in eliminating, hundreds of indigenous cultures.

Gregory D. Smithers, a lecturer in the Department of History at the University of Aberdeen, has weighed in as well.

Ward Churchill refers to settler colonialism in North America as ‘the American holocaust’, and David Stannard similarly portrays the European colonization of the Americas as an example of ‘human incineration and carnage’.

According to Mahmood Mamdani, in general, Indigenous societies did not necessarily consider land private property. Australian anthropologist Patrick Wolfe says that physical removal from their land resulted in the loss of means of subsistence, as the land was privatized and off limits to Indigenous peoples. Some Western thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes rationalized the appropriation of land saying that the land belonged to those that developed it.

Historian Samuel Totten and professor Robert K. Hitchcock stated the following in their historiography work:

...It was only in the latter part of the twentieth century that the genocide of Indigenous peoples started to become a significant issue for human rights activists, non-governmental organizations, international development and finance institutions, such as the United Nations and the World Bank, and indigenous and other community-based organizations...

Robert K. Hitchcock and Tara M. Twedt have stated that even though many countries have stated commitments to the rights of minorities, numerous countries have repressed their own citizens:

Most states, along with the United Nations, have been reluctant to criticize individual nations for their actions on the pretense that this would constitute a violation of sovereignty. They have also tended to accept government denials of genocides at face value. As a result, genocidal actions continue.

According to South African scholar Leo Kuper, explained why the genocide of Indigenous peoples has been dismissed in academic studies:

Much colonization proceeded without genocidal conflict … But the effects of colonial settlement were quite variable, dependent on a variety of factors, such as the number of settlers, the forms of the colonizing economy and competition for productive resources, policies of the colonizing power, and attitudes to intermarriage or concubinage … Some of the annihilations of indigenous peoples arose not so much by deliberate act, but in the course of what may be described as a genocidal process: massacres, appropriation of land, introduction of diseases, and arduous conditions of labor.

Dr. Rita Dhamoon layed a number criticisms of the Canadian Museum of Human Rights (CMHR) including the centrality of the Holocaust in the museum, framing residential schools as assimilationism and not genocide, and denialism of the genocidal nature of settler colonialism:

I contend that the curatorial decision of the CMHR to not use the label of genocide in the title of the core gallery on Indigenous perspectives was specifically a form of interpretive denial.

In Australia, according to Hannah Baldry there is ongoing denial: "The Australian Government appears to have long suffered a form of ‘denialism’ that has consistently deprived the country’s Aboriginal population of acknowledgment of the crimes perpetrated against their ancestors." According to Australian historian Colin Tatz, this denialism has taken several forms:

Denialism takes several forms. First, the denial of any past genocidal behavior, whether physical killing or child removal. Second, the somewhat bizarre counterview that whites have been the victims. Third, the hypothesis that concentration on unmitigated gloom, or on the black armband view of history, overwhelms the reality that there has been more good than bad in Australian race relations.

Mark Levene is a historian at University of Southampton, linked colonialism and genocide:

In this, of course, we come back to the fatal nexus between the Anglo-American drive to rapid state-building and genocide.

The Spanish colonial process was criticized in Spanish Black Legend works of rival European powers. Historians have noted that the abused of Indigenous peoples was practiced by most European powers which colonized the Americas. The historiographical evaluation of the Impact of Western European colonialism and colonisation continues to evolve. According to scholar William B. Maltby: "At least three generations of scholarship have produced a more balanced appreciation of Spanish conduct in both the Old World and the New, while the dismal records of other imperial powers have received a more objective appraisal."

David Stannard historian and Professor of American Studies at the University of Hawaii compares the genocidal process in two cases, and indicts both of them:

And therein lies the central difference between the genocide committed by the Spanish and that of the Anglo-Americans: in British America extermination was the primary goal.

Ann Curthoys is an Australian historian and academic writes about the view of Leo Kuper:

Nevertheless, the course of colonization of North and South America, the West Indies, and Australia and Tasmania, [Leo] Kuper observes, has certainly been marked all too often by genocide.

Roxxane Dunbar-Ortiz, an American historian, Professor at California State University, describes settler colonialism:

Settler colonialism is inherently genocidal in terms of the genocide convention. In the case of the British North American colonies and the United States, not only extermination and removal were practiced but also the disappearing of the prior existence of Indigenous peoples, and this continues to be perpetuated in local histories.

Benjamin Madley has described the atrocities against Indigenous peoples in California as genocide, as does Mohamed Adhikari, and historian Brendan Lindsay. Benjamin Madley claims that there is denial of atrocities:

Justice demands that even long after the perpetrators have vanished, we document the crimes that they and their advocates have too often concealed, denied, or suppressed.

Madley also highlights that the Genocide Convention designates genocide a crime whether committed in time of peace or war. He has argued that the violent resistance to genocide has been described as a war, instead of a genocide or a war of resistance. For example, for every white man killed, a hundred [California] Indians paid the penalty with their lives. He proposed a case study of the Modoc War, comparing details of both sides in the conflict, to support this point:

Like Armenians, Jews, Cambodians, and Tutsis, Modocs violently resisted genocide. Variations of the Modoc ordeal occurred elsewhere during the conquest and colonization of Africa, Asia, Australia, and North and South America. Indigenous civilizations repeatedly resisted invaders seeking to physically annihilate them in whole or in part. Many of these catastrophes are known as wars. Yet by carefully examining the intentions and actions of colonizers and their advocates it is possible to reinterpret some of these cataclysms as both genocides and wars of resistance. The Modoc case is one of them.

Madley studied two cases of genocide (Pequot and Yuki) analyzing four elements: statements of genocidal intent, presence of massacres, state-sponsored body-part bounties (rewards officially paid for corpses, heads and scalps) and mass death in government custody. He lists other cases and suggests that detailed breakdown of genocide studies by individual tribe or nation is a new direction in genocide studies to combat its denial: "...offering a powerful tool with which to understand genocide and combat its denial around the world."

Stanford professor Richard White says that Madley believes that Native American genocides need a name, and observes:

In defining genocide, Madley relies on the criteria of the United Nations Genocide Convention, which has served as the basis for the genocide trials of defendants from Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia and has been employed at the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

Stephen Howe, Professor in the History and Cultures of Colonialism at the University of Bristol, UK, relates colonialism with genocide:

The crucial relevance of this to debates over colonial violence lies in the argument, made in recent years in many different contexts and with unprecedented force, that settler colonialism is inherently bound up with extreme, pervasive, structural and even genocidal violence....And quite simply, since Britain (and, before a United Kingdom or a compound British identity were formed, England) founded more and more successful, ‘explosive’ settler colonies than anyone else, so probably more alleged or potential cases of pre-twentieth century genocide occurred in the British world than anywhere outside it…For British North America and for Australasia, however, the case for numerous genocidal episodes –by even restricted definitions, since large-scale deliberate killing was repeatedly involved– seems to me very strong.

In 1999, Adam Hochschild published King Leopold's Ghost, a book about the atrocities committed in the Congo Free State. The book became the basis for a 2006 eponymous documentary.

Academic Ward Churchill argues that the Indigenous populations of the Americas were subjected to a systematic campaign of extermination by settler colonialism in what is now known as the United States. He discusses American policies such as the Indian Removal Act and the forced assimilation of Indigenous children in American Indian boarding schools operating in the mid-1800s to early 1900s. The United States ratified the Genocide Convention forty years later until 1986, and did so with conditions. He has called manifest destiny an ideology used to justify dispossession and genocide against Native Americans, and compared it to Lebensraum ideology of Nazi Germany.

Professor Elazar Barkan claims that Indigenous genocide has not been given a place in the dominant version of history, particularly in the history of the United States: "Only wide recognition of indigenous destruction as genocide will acknowledge such opinion as denial. At present, these are more likely uninformed opinions."

Noam Chomsky has considered settler colonialism to be related to imperialism, and describes the lack of self-awareness of parts of American history:

Settler colonialism, commonly the most vicious form of imperial conquest, provides striking illustrations. The English colonists in North America had no doubts about what they were doing. Revolutionary War hero General Henry Knox, the first Secretary of War in the newly liberated American colonies, described "the utter extirpation of all the Indians in most populous parts of the Union" by means "more destructive to the Indian natives than the conduct of the conquerors of Mexico and Peru", which would have been no small achievement. In his later years, President John Quincy Adams recognized the fate of "that hapless race of native Americans, which we are exterminating with such merciless and perfidious cruelty, [to be] among the heinous sins of this nation, for which I believe God will one day bring [it] to judgement".

Chomsky postulates genocide within a context of colonialism, and concludes:

Take just north of the Rio Grande, where once there were maybe 10 or 12 million native Americans. By 1900 there were about 200,000. In the Andean region and Mexico there were very extensive Indian societies, and they’re mostly gone. Many of them were just totally murdered or wiped out, others succumbed to European-brought diseases. This is massive genocide, long before the emergence of the twentieth century nation-state. It may be one of the most, if not the most extreme example from history, but far from the only one. These are facts that we don't recognize.

Other personalities

Phil Fontaine, former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, wrote:

The Government of Canada currently recognizes five genocides: the Holocaust, the Holodomor, the Armenian genocide, the Rwandan genocide and Srebrenica. The time has come for Canada to formally recognize a sixth genocide, the genocide of its own aboriginal communities;

Members of the Penobscot Nation in Maine made an educational film about how settlers killed Indigenous people during the colonial era:

The filmmakers say they simply want to ensure this history isn't whitewashed by promoting a fuller understanding of the nation's past.

Indigenous actor Russell Means wrote about denial in 1992, inspiring the title of a book by Ward Churchill:

...there's a little matter of genocide that's got to be taken into account right here at home. I’m talking about the genocide which has been perpetrated against American Indians...

American actor Marlon Brando declined an Academy Award in protest for the representation of Native Americans in Hollywood cinema.

Prevention

Atrocity crimes denial may be reduced by works of history, knowledge gathering, preservation of archives, documentation of records, investigation panels, international tribunals, application of international law, search for missing persons, commemorations, public apologies, development of truth commissions, educational programs, memorials, museums, documentaries, films and other mass media. According to Johnathan Sisson, the society has the right to know the truth about historical events and facts, and the circumstances that led to massive or systematic human rights violations. He says that the State has the obligation to secure records and other evidence to prevent historical revisionism. The goal is to prevent recurrence in the future.