The genetic history of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas is divided into two distinct periods: the initial peopling of the Americas during about 20,000 to 14,000 years ago (20–14 kya), and European contact, after about 500 years ago. The first period of Indigenous American genetic history is the determinant factor for the number of genetic lineages, zygosity mutations and founding haplotypes present in today's Indigenous American populations.

Most Indigenous American groups are derived from two ancestral lineages, which formed in Siberia prior to the Last Glacial Maximum, between about 36,000 and 25,000 years ago, East Eurasian and Ancient North Eurasian. They later dispersed throughout the Americas after about 16,000 years ago (exceptions being the Na-Dene and Eskimo–Aleut speaking groups, which are derived partially from Siberian populations which entered the Americas at a later time).

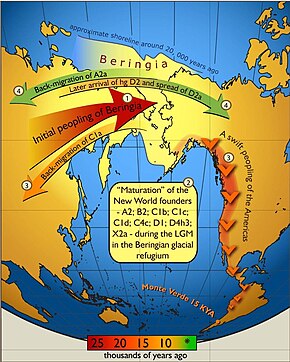

Analyses of genetics among Indigenous American and Siberian populations have been used to argue for early isolation of founding populations on Beringia and for later, more rapid migration from Siberia through Beringia into the New World. The microsatellite diversity and distributions of the Y lineage specific to South America indicates that certain Indigenous American populations have been isolated since the initial peopling of the region. The Na-Dene, Inuit and Native Alaskan populations exhibit Haplogroup Q-M242; however, they are distinct from other Indigenous Americans with various mtDNA and atDNA mutations. This suggests that the peoples who first settled in the northern extremes of North America and Greenland derived from later migrant populations than those who penetrated farther south in the Americas. Linguists and biologists have reached a similar conclusion based on analysis of Indigenous American language groups and ABO blood group system distributions.

Autosomal DNA

Genetic diversity and population structure in the American landmass is also measured using autosomal (atDNA) micro-satellite markers genotyped; sampled from North, Central, and South America and analyzed against similar data available from other Indigenous populations worldwide. The Indigenous American populations show a lesser genetic diversity than populations from other continental regions. Observed is a decreasing genetic diversity as geographic distance from the Bering Strait occurs, as well as a decreasing genetic similarity to Siberian populations from Alaska (the genetic entry point). Also observed is evidence of a greater level of diversity and lesser level of population structure in western South America compared to eastern South America. There is a relative lack of differentiation between Mesoamerican and Andean populations, a scenario that implies that coastal routes (in this case along the coast of the Pacific Ocean) were easier for migrating peoples (more genetic contributors) to traverse in comparison with inland routes.

The over-all pattern that is emerging suggests that the Americas were colonized by a small number of individuals (effective size of about 70), which grew by many orders of magnitude over 800 – 1000 years. The data also shows that there have been genetic exchanges between Asia, the Arctic, and Greenland since the initial peopling of the Americas.

According to an autosomal genetic study from 2012, Indigenous Americans descend from at least three main migrant waves from East Asia. Most of it is traced back to a single ancestral population, called 'First Americans'. However, those who speak Inuit languages from the Arctic inherited almost half of their ancestry from a second East Asian migrant wave. And those who speak Na-Dene, on the other hand, inherited a tenth of their ancestry from a third migrant wave. The initial settling of the Americas was followed by a rapid expansion southwards along the west coast, with little gene flow later, especially in South America. One exception to this are the Chibcha speakers of Colombia, whose ancestry comes from both North and South America.

In 2014, the autosomal DNA of a 12,500+ year old infant from Montana was sequenced. The DNA was taken from a skeleton referred to as Anzick-1, found in close association with several Clovis artifacts. Comparisons showed strong affinities with DNA from Siberian sites, and virtually ruled out that particular individual had any close affinity with European sources (the "Solutrean hypothesis"). The DNA also showed strong affinities with all existing Indigenous American populations, which indicated that all of them derive from an ancient population that lived in or near Siberia.

Linguistic studies have reinforced genetic studies, with relationships between languages found among those spoken in Siberia and those spoken in the Americas.

Two 2015 autosomal DNA genetic studies confirmed the Siberian origins of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. However an ancient signal of shared ancestry with Australasians (Indigenous peoples of Australia, Melanesia and the Andaman Islands) was detected among the Indigenous peoples of the Amazon region. The migration coming out of Siberia would have happened 23,000 years ago.

A 2018 study analysed 11,500 BCE old Indigenous samples. The genetic evidence suggests that all Indigenous Americans ultimately descended from a single founding population that initially split from a Basal-East Asian source population in Mainland Southeast Asia around 36,000 years ago, the same time at which the proper Jōmon people divided from Basal-East Asians, either together with Ancestral Indigenous Americans or during a separate expansion wave. The authors also provided evidence that the basal northern and southern Indigenous American branches, to which all other Indigenous peoples belong, diverged around 16,000 years ago. An Indigenous American sample from 16,000 BCE in Idaho, which is craniometrically similar to modern Indigenous Americans as well as Paleosiberians, was found to have been largely East-Eurasian genetically, and showed high affinity with contemporary East Asians, as well as Jōmon period samples of Japan, confirming that Ancestral Indigenous Americans split from an East-Eurasian source population somewhere in eastern Siberia.

A study published in the Nature journal in 2018 concluded that Indigenous Americans descended from a single founding population which initially divided from East Asians about ~36,000 BCE, with gene flow between Ancestral Indigenous Americans and Siberians persisting until ~25,000 BCE, before becoming isolated in the Americas at ~22,000 BCE. Northern and Southern American Indigenous sub-populations split from each other at ~17,500 BCE. There is also some evidence for a back-migration from the Americas into Siberia after ~11,500 BCE.

A study published in the Cell journal in 2019, analysed 49 ancient Indigenous American samples from all over North and South America, and concluded that all Indigenous American populations descended from a single ancestral source population which divided from Siberians and East Asians, and gave rise to the Ancestral Indigenous Americans, which later diverged into the various Indigenous groups. The authors further dismissed previous claims for the possibility of two distinct population groups among the peopling of the Americas. Both, Northern and Southern Indigenous Americans are closest to each other, and do not show evidence of admixture with hypothetical previous populations.

A review article published in the Nature journal in 2021, which summarized the results of previous genomic studies, similarly concluded that all Indigenous Americans descended from the movement of people from Northeast Asia into the Americas. These Ancestral Americans, once south of the continental ice sheets, spread and expanded rapidly, and branched into multiple groups, which later gave rise to the major subgroups of Indigenous American populations. The study also dismissed the existence, inferred from craniometric data, of a hypothetical distinct non-Indigenous American population (suggested to have been related to Indigenous Australians and Papuans), sometimes called "Paleoamerican".

Overall, the 'Ancestral Native Americans' formed from an 'Ancestral Native American' lineage which diverged from East Asian people around 36,000 years ago, and subsequently migrated northwards into Siberia and encountered/interacted with a distinct Paleolithic Siberian population known as Ancient North Eurasians, closer related to modern Europeans, giving rise to both Indigenous peoples of Siberia and Native Americans.

Y-chromosome DNA

A "Central Siberian" origin has been postulated for the paternal lineage of the source populations of the original migration into the Americas.

Membership in haplogroups Q and C3b implies Indigenous American patrilineal descent.

The micro-satellite diversity and distribution of a Y lineage specific to South America suggest that certain Indigenous American populations became isolated after the initial colonization of their regions. The Na-Dene, Inuit, and Native Alaskan populations exhibit haplogroup Q (Y-DNA) mutations, but are distinct from other Indigenous Americans with various mtDNA and autosomal DNA (atDNA) mutations. This suggests that the earliest migrants into the northern extremes of North America and Greenland derived from later migrant populations.

Haplogroup Q

Q-M242 (mutational name) is the defining (SNP) of Haplogroup Q (Y-DNA) (phylogenetic name). In Eurasia, haplogroup Q is found among Indigenous Siberian populations, such as the modern Chukchi and Koryak peoples, as well as some Southeast Asians, such as the Dayak people. In particular, two groups exhibit large concentrations of the Q-M242 mutation, the Ket (93.8%) and the Selkup (66.4%) peoples. The Ket are thought to be the only survivors of ancient wanderers living in Siberia. Their population size is very small; there are fewer than 1,500 Ket in Russia. The Selkup have a slightly larger population size than the Ket, with approximately 4,250 individuals.

Starting the Paleo-Indigenous American period, a migration to the Americas across the Bering Strait (Beringia) by a small population carrying the Q-M242 mutation occurred. A member of this initial population underwent a mutation, which defines its descendant population, known by the Q-M3 (SNP) mutation. These descendants migrated all over the Americas.

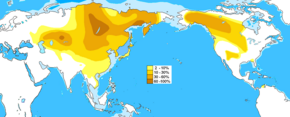

Haplogroup Q-M3 is defined by the presence of the rs3894 (M3) (SNP). The Q-M3 mutation is roughly 15,000 years old as that is when the initial migration of Paleo-Indigenous Americans into the Americas occurred. Q-M3 is the predominant haplotype in the Americas, at a rate of 83% in South American populations, 50% in the Na-Dene populations, and in North American Eskimo-Aleut populations at about 46%. With minimal back-migration of Q-M3 in Eurasia, the mutation likely evolved in east-Beringia, or more specifically the Seward Peninsula or western Alaskan interior. The Beringia land mass began submerging, cutting off land routes.

Since the discovery of Q-M3, several subclades of M3-bearing populations have been discovered. An example is in South America, where some populations have a high prevalence of (SNP) M19, which defines subclade Q-M19. M19 has been detected in (59%) of Amazonian Ticuna men and in (10%) of Wayuu men. Subclade M19 appears to be unique to South American Indigenous peoples, arising 5,000 to 10,000 years ago. This suggests that population isolation, and perhaps even the establishment of tribal groups, began soon after migration into the South American areas. Other American subclades include Q-L54, Q-Z780, Q-MEH2, Q-SA01, and Q-M346 lineages. In Canada, two other lineages have been found. These are Q-P89.1 and Q-NWT01.

Haplogroup R1

Haplogroup R1 is the second most common Y-DNA haplogroup found among Indigenous Americans after Y-DNA haplogroup Q. It is believed that R1 was introduced through admixture during the post-1492 European settlement of the Americas.

R1 (M173) is found predominantly in North American groups like the Ojibwe (50-79%), Seminole (50%), Sioux (50%), Cherokee (47%), Dogrib (40%) and Tohono O'odham (Papago) (38%). Its highest frequency is found in northeastern North America, and declines in frequency from east to west.

Haplogroup C-P39

Haplogroup C-M217 is found mainly in Indigenous Siberians, Mongolians, and Kazakhs. Haplogroup C-M217 is the most widespread and frequently occurring branch of the greater (Y-DNA) haplogroup C-M130. Haplogroup C-M217 descendant C-P39 is most commonly found in today's Na-Dene speakers, with the greatest frequency found among the Athabaskans at 42%, and at lesser frequencies in some other Indigenous American groups. This distinct and isolated branch C-P39 includes almost all the Haplogroup C-M217 Y-chromosomes found among all Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Some researchers feel that this may indicate that the Na-Dene migration occurred from the Russian Far East after the initial Paleo-Indigenous American colonization, but prior to modern Inuit, Inupiat and Yupik expansions.

In addition to in Na-Dene peoples, haplogroup C-P39 (C2b1a1a) is also found among other Indigenous Americans such as Algonquian- and Siouan-speaking populations. C-M217 is found among the Wayuu people of Colombia and Venezuela.

Data

Mitochondrial DNA

The common occurrence of the mtDNA Haplogroups A, B, C, and D among eastern Asian and Indigenous American populations has long been recognized, along with the presence of Haplogroup X. As a whole, the greatest frequency of the four Indigenous American associated haplogroups occurs in the Altai-Baikal region of southern Siberia. Some subclades of C and D closer to the Indigenous American subclades occur among Mongolian, Amur, Japanese, Korean, and Ainu populations.

When studying human mitochondrial DNA haplogroup, the results indicated that Indigenous American haplogroups, including haplogroup X, are part of a single founding East Asian population. It also indicates that the distribution of mtDNA haplogroups and the levels of sequence divergence among linguistically similar groups were the result of multiple preceding migrations from Bering Straits populations. All Indigenous American mtDNA can be traced back to five haplogroups, A, B, C, D and X. More specifically, Indigenous American mtDNA belongs to sub-haplogroups A2, B2, C1b, C1c, C1d, D1, and X2a (with minor groups C4c, D2a, and D4h3a). This suggests that 95% of Indigenous American mtDNA is descended from a minimal genetic founding female population, comprising sub-haplogroups A2, B2, C1b, C1c, C1d, and D1. The remaining 5% is composed of the X2a, D2a, C4c, and D4h3a sub-haplogroups.

X is one of the five mtDNA haplogroups found in Indigenous Americans. Native Americans mostly belong to the X2a clade, which has never been found in the Old World. According to Jennifer Raff, X2a probably originated in the same Siberian population as the other four founding maternal lineages.

Haplogroup X genetic sequences diverged about 20,000 to 30,000 years ago to give two sub-groups, X1 and X2. X2's subclade X2a occurs only at a frequency of about 3% for the total current Indigenous population of the Americas. However, X2a is a major mtDNA subclade in North America; among the Algonquian peoples, it comprises up to 25% of mtDNA types. It is also present in lower percentages to the west and south of this area — among the Sioux (15%), the Nuu-chah-nulth (11%–13%), the Navajo (7%), and the Yakama (5%). The predominant theory for sub-haplogroup X2a's appearance in North America is migration along with A, B, C, and D mtDNA groups, from a source in the Altai Mountains of central Asia. Haplotype X6 was present in the Tarahumara 1.8% (1/53) and Huichol 20% (3/15)

Sequencing of the mitochondrial genome from Paleo-Eskimo

remains (3,500 years old) are distinct from modern Indigenous

Americans, falling within sub-haplogroup D2a1, a group observed among

today's Aleutian Islanders, the Aleut and Siberian Yupik populations. This suggests that the colonizers of the far north, and subsequently Greenland, originated from later coastal populations. Then a genetic exchange in the northern extremes introduced by the Thule people (proto-Inuit) approximately 800–1,000 years ago began.

These final Pre-Columbian migrants introduced haplogroups A2a and A2b

to the existing Paleo-Eskimo populations of Canada and Greenland,

culminating in the modern Inuit.

A route through Beringia is seen as more likely than the Solutrean hypothesis. An abstract in a 2012 issue of the "American Journal of Physical Anthropology" states that "The similarities in ages and geographical distributions for C4c and the previously analyzed X2a lineage provide support to the scenario of a dual origin for Paleo-Indigenous Americans. Taking into account that C4c is deeply rooted in the Asian portion of the mtDNA phylogeny and is indubitably of Asian origin, the finding that C4c and X2a are characterized by parallel genetic histories definitively dismisses the controversial hypothesis of an Atlantic glacial entry route into North America."

Another study, also focused on the mtDNA (that which is inherited through only the maternal line), revealed that the Indigenous people of the Americas have their maternal ancestry traced back to a few founding lineages from East Asia, which would have arrived via the Bering strait. According to this study, it is probable that the ancestors of the Indigenous Americans would have remained for a time in the region of the Bering Strait, after which there would have been a rapid movement of settling of the Americas, taking the founding lineages to South America.

According to a 2016 study, focused on mtDNA lineages, "a small population entered the Americas via a coastal route around 16.0 ka, following previous isolation in eastern Beringia for ~2.4 to 9 thousand years after separation from eastern Siberian populations. Following a rapid movement throughout the Americas, limited gene flow in South America resulted in a marked phylogeographic structure of populations, which persisted through time. All of the ancient mitochondrial lineages detected in this study were absent from modern data sets, suggesting a high extinction rate. To investigate this further, we applied a novel principal components multiple logistic regression test to Bayesian serial coalescent simulations. The analysis supported a scenario in which European colonization caused a substantial loss of pre-Columbian lineages".

Genetic admixture

Ancient Beringians

Recent archaeological findings in Alaska have shed light on the existence of a previously unknown Indigenous American population that has been academically named "Ancient Beringians." Although it is popularly agreed among archeologists that early settlers had crossed into Alaska from Russia through the Bering Strait land bridge, the issue of whether or not there was one founding group or several waves of migration is a controversial and prevalent debate among academics in the field today. In 2018, the sequenced DNA of a Indigenous girl, whose remains were found at the Sun River archaeological site in Alaska in 2013, proved not to match the two recognized branches of Indigenous Americans and instead belonged to the early population of Ancient Beringians. This breakthrough is said to be the first direct genomic evidence that there was potentially only one wave of migration in the Americas that occurred, with genetic branching and division transpiring after the fact. The migration wave is estimated to have emerged about 20,000 years ago. The Ancient Beringians are said to be a common ancestral group among contemporary Indigenous American populations today, which differs in results collected from previous research that suggests that modern populations are descendants of either Northern and Southern branches. Experts were also able to use wider genetic evidence to establish that the split between the Northern and Southern American branches of civilization from the Ancient Beringians in Alaska only occurred about 17,000 and 14,000 years, further challenging the concept of multiple migration waves occurring during the very first stages of settlement.

Genetic evidence for Paleo-Indigenous Americans consists of the presence of apparent admixture of archaic Sundadont lineages to the remote populations in the South American rain forest, and in the genetics of Patagonians-Fuegians.

Nomatto et al. (2009) proposed migration into Beringia occurred between 40k and 30k cal years BP, with a pre-LGM migration into the Americas followed by isolation of the northern population following closure of the ice-free corridor.

A 2016 genetic study of Indigenous peoples of the Amazonian region of Brazil (by Skoglund and Reich) showed evidence of admixture from a separate lineage of an otherwise unknown ancient people. This ancient group appears to be related to modern day "Australasian" peoples (i.e. Aboriginal Australians and Melanesians). This "Ghost population" was found in speakers of Tupian languages. They provisionally named this ancient group; "Population Y", after Ypykuéra, "which means 'ancestor' in the Tupi language family". A 2021 genetic study dismissed the existence of an hypothetical Australasian component among Indigenous Americans. The signal of the hypothetical Australasian component, can also be reproduced using the Basal-East Asian Tianyuan man sample, and thus does not represent "real Australasian affinity". The authors explained that the previous claims of possibly Australasian ancestry were based on a misinterpreted genetic echo, which was revealed to represent early East-Eurasian gene flow (represented by the 40,000 BCE old Tianyuan sample) into Aboriginal Australians and Papuans, which was lost in modern East Asians.

Archaeological evidence for pre-LGM human presence in the Americas was first presented in the 1970s. notably the "Luzia Woman" skull found in Brazil.

Old world

Substantial racial admixture has taken place during and since the European colonization of the Americas.

South and Central America

In Latin America in particular, significant racial admixture took place between the Indigenous American population, the European-descended colonial population, and the Sub-Saharan African populations imported as slaves. From about 1700, a Latin American terminology developed to refer to the various combinations of mixed racial descent produced by this.

Many individuals who self-identify as one race exhibit genetic evidence of a multiracial ancestry. The European conquest of South and Central America, beginning in the late 15th century, was initially executed by male soldiers and sailors from the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal). The new soldier-settlers fathered children with Indigenous American women and later with African slaves. These mixed-race children were generally identified by the Spanish colonist and Portuguese colonist as "Castas".

North America

The North American fur trade during the 16th century brought many more European men, from France, Ireland, and Great Britain, who took Indigenous North American women as wives. Their children became known as "Métis" or "Bois-Brûlés" by the French colonists and "mixed-bloods", "half-breeds" or "country-born" by the English colonists and Scottish colonists.

Indigenous Americans in the United States are more likely than any other racial group to practice racial exogamy, resulting in an ever-declining proportion of Indigenous ancestry among those who claim an Indigenous American identity. In the United States 2010 census, nearly 3 million people indicated that their race was Indigenous American (including Alaskan Native). This is based on self-identification, and there are no formal defining criteria for this designation. Especially numerous was the self-identification of Cherokee ethnic origin, a phenomenon dubbed the "Cherokee Syndrome", where some Americans believe they have a "long-lost Cherokee ancestor" without being able to identify that person in their family tree. The context is the cultivation of an opportunistic ethnic identity related to the perceived prestige associated with Indigenous American ancestry. Indigenous American identity in the Eastern United States is mostly detached from genetic descent, and especially embraced by people of predominantly European ancestry. Some tribes have adopted criteria of racial preservation, usually through a Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood, and practice disenrollment of tribal members unable to provide proof of Native American ancestry. This topic has become a contentious issue in Native American reservation politics.

European diseases and genetic modification

A team led by Ripan Malhi, an anthropologist at the University of Illinois in Urbana, conducted a study where they used a scientific technique known as whole exome sequencing to test immune-related gene variants within Indigenous Americans. Through analyzing ancient and modern Indigenous DNA, it was found that HLA-DQA1, a variant gene that codes for protein in charge of differentiating between healthy cells from invading viruses and bacteria were present in nearly 100% of ancient remains but only 36% in modern Indigenous Americans. These finding suggest that European-borne epidemics such as smallpox altered the disease landscape of the Americas, leaving survivors of these outbreaks less likely to carry variants like HLA-DQA1. This made them less able to cope with new diseases. The change in genetic makeup is measured by scientists to have occurred around 175 years ago, during a time when the smallpox epidemic was ranging through the Americas.

Blood groups

Prior to the 1952 confirmation of DNA as the hereditary material by Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase, scientists used blood proteins to study human genetic variation. The ABO blood group system is widely credited to have been discovered by the Austrian Karl Landsteiner, who found three different blood types in 1900. Blood groups are inherited from both parents. The ABO blood type is controlled by a single gene (the ABO gene) with three alleles: i, IA, and IB.

Research by Ludwik and Hanka Herschfeld during World War I found that the frequencies of blood groups A, B and O differed greatly from region to region. The "O" blood type (usually resulting from the absence of both A and B alleles) is very common around the world, with a rate of 63% in all human populations. Type "O" is the primary blood type among the Indigenous populations of the Americas, particularly within Central and South American populations, with a frequency of nearly 100%. In Indigenous North American populations the frequency of type "A" ranges from 16% to 82%. This suggests again that the initial Indigenous Americans evolved from an isolated population with a minimal number of individuals.

The standard explanation for such a high population of Indigenous Americans with blood type O is genetic drift. Because the ancestral population of Indigenous Americans was numerically small, blood type diversity could have been reduced from generation to generation by the founder effect. Other related explanations include the Bottleneck explanation which states that there were high frequencies of blood type A and B among Indigenous Americans but severe population decline during the 1500s and 1600s caused by the introduction of disease from Europe resulted in the massive death toll of those with blood types A and B. Coincidentally, a large amount of the survivors were type O.

| PEOPLE GROUP | O (%) | A (%) | B (%) | AB (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blackfoot Confederacy (Indigenous North American) | 17 | 82 | 0 | 1 |

| Bororo (Brazil) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Eskimos (Alaska) | 38 | 44 | 13 | 5 |

| Inuit (Eastern Canada & Greenland) | 54 | 36 | 23 | 8 |

| Hawaiians (Polynesians, non-Indigenous American) | 37 | 61 | 2 | 1 |

| Indigenous North Americans (as a whole Native Nations/First Nations) | 79 | 16 | 4 | 1 |

| Maya (modern) | 98 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Navajo | 73 | 27 | 0 | 0 |

| Peru | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The Dia antigen of the Diego antigen system has been found only in Indigenous peoples of the Americas and East Asians, and in people with some ancestry from those groups. The frequency of the Dia antigen in various groups of Indigenous peoples of the Americas ranges from almost 50% to 0%. Differences in the frequency of the antigen in populations of Indigenous people in the Americas correlate with major language families, modified by environmental conditions.