Tumor necrosis factor (TNF, cachexin, or cachectin; formerly known as tumor necrosis factor alpha or TNF-α) is an adipokine and a cytokine. TNF is a member of the TNF superfamily, which consists of various transmembrane proteins with a homologous TNF domain.

As an adipokine, TNF promotes insulin resistance, and is associated with obesity-induced type 2 diabetes. As a cytokine, TNF is used by the immune system for cell signaling. If macrophages (certain white blood cells) detect an infection, they release TNF to alert other immune system cells as part of an inflammatory response.

TNF signaling occurs through two receptors: TNFR1 and TNFR2. TNFR1 is constituitively expressed on most cell types, whereas TNFR2 is restricted primarily to endothelial, epithelial, and subsets of immune cells. TNFR1 signaling tends to be pro-inflammatory and apoptotic, whereas TNFR2 signaling is anti-inflammatory and promotes cell proliferation. Suppression of TNFR1 signaling has been important for treatment of autoimmune disease, whereas TNFR2 signaling promotes wound healing.

TNF-α exists as a transmembrane form (mTNF-α) and as a soluble form (sTNF-α). sTNF-α results from enzymatic cleavage of mTNF-α, by a process called substrate presentation. mTNF-α is mainly found on monocytes/macrophages where it interacts with tissue receptors by cell-to-cell contact. sTNF-α selectively binds to TNFR1, whereas mTNF-α binds to both TNFR1 and TNFR2. TNF-α binding to TNFR1 is irreversible, whereas binding to TNFR2 is reversible.

The primary role of TNF is in the regulation of immune cells. TNF, as an endogenous pyrogen, is able to induce fever, apoptotic cell death, cachexia, and inflammation, inhibit tumorigenesis and viral replication, and respond to sepsis via IL-1 and IL-6-producing cells. Dysregulation of TNF production has been implicated in a variety of human diseases including Alzheimer's disease, cancer, major depression, psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Though controversial, some studies have linked depression and IBD to increased levels of TNF.

Under the name tasonermin, TNF is used as an immunostimulant drug in the treatment of certain cancers. Drugs that counter the action of TNF are used in the treatment of various inflammatory diseases, for instance rheumatoid arthritis.

Certain cancers can cause overproduction of TNF. TNF parallels parathyroid hormone both in causing secondary hypercalcemia and in the cancers with which excessive production is associated.

Discovery

The theory of an anti-tumoral response of the immune system in vivo was recognized by the physician William B. Coley. In 1968, Gale A Granger from the University of California, Irvine, reported a cytotoxic factor produced by lymphocytes and named it lymphotoxin (LT). Credit for this discovery is shared by Nancy H. Ruddle from Yale University, who reported the same activity in a series of back-to-back articles published in the same month. Subsequently, in 1975 Lloyd J. Old from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, reported another cytotoxic factor produced by macrophages and named it tumor necrosis factor (TNF). Both factors were described based on their ability to kill mouse fibrosarcoma L-929 cells. These concepts were extended to systemic disease in 1981, when Ian A. Clark, from the Australian National University, in collaboration with Elizabeth Carswell in Old's group, working with pre-sequencing era data, reasoned that excessive production of TNF causes malaria disease and endotoxin poisoning.

The cDNAs encoding LT and TNF were cloned in 1984 and were revealed to be similar. The binding of TNF to its receptor and its displacement by LT confirmed the functional homology between the two factors. The sequential and functional homology of TNF and LT led to the renaming of TNF as TNFα and LT as TNFβ. In 1985, Bruce A. Beutler and Anthony Cerami discovered that cachectin (a hormone which induces cachexia) was actually TNF. They then identified TNF as a mediator of lethal endotoxin poisoning. Kevin J. Tracey and Cerami discovered the key mediator role of TNF in lethal septic shock, and identified the therapeutic effects of monoclonal anti-TNF antibodies.

Research in the Laboratory of Mark Mattson has shown that TNF can prevent the death/apoptosis of neurons by a mechanism involving activation of the transcription factor NF-κB which induces the expression of antioxidant enzymes and Bcl-2.

Gene

The human TNF gene was cloned in 1985. It maps to chromosome 6p21.3, spans about 3 kilobases and contains 4 exons. The last exon shares similarity with lymphotoxin alpha (LTA, once named as TNF-β). The three prime untranslated region (3'-UTR) of TNF contains an AU-rich element (ARE).

Structure

TNF is primarily produced as a 233-amino acid-long type II transmembrane protein arranged in stable homotrimers. From this membrane-integrated form the soluble homotrimeric cytokine (sTNF) is released via proteolytic cleavage by the metalloprotease TNF alpha converting enzyme (TACE, also called ADAM17). The soluble 51 kDa trimeric sTNF tends to dissociate at concentrations below the nanomolar range, thereby losing its bioactivity. The secreted form of human TNF takes on a triangular pyramid shape, and weighs around 17-kDa. Both the secreted and the membrane bound forms are biologically active, although the specific functions of each is controversial. But, both forms do have overlapping and distinct biological activities.

The common house mouse TNF and human TNF are structurally different. The 17-kilodalton (kDa) TNF protomers (185-amino acid-long) are composed of two antiparallel β-pleated sheets with antiparallel β-strands, forming a 'jelly roll' β-structure, typical for the TNF family, but also found in viral capsid proteins.

Cell signaling

TNF can bind two receptors, TNFR1 (TNF receptor type 1; CD120a; p55/60) and TNFR2 (TNF receptor type 2; CD120b; p75/80). TNFR1 is 55-kDa and TNFR2 is 75-kDa. TNFR1 is expressed in most tissues, and can be fully activated by both the membrane-bound and soluble trimeric forms of TNF, whereas TNFR2 is found typically in cells of the immune system, and responds to the membrane-bound form of the TNF homotrimer. As most information regarding TNF signaling is derived from TNFR1, the role of TNFR2 is likely underestimated. At least partly because TNFR2 has no intracellular death domain, it shows neuroprotective properties.

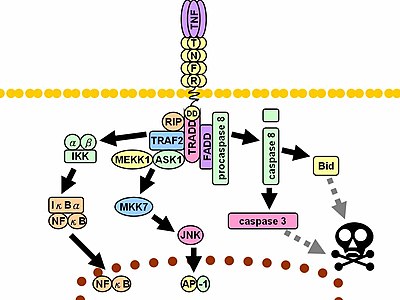

Upon contact with their ligand, TNF receptors also form trimers, their tips fitting into the grooves formed between TNF monomers. This binding causes a conformational change to occur in the receptor, leading to the dissociation of the inhibitory protein SODD from the intracellular death domain. This dissociation enables the adaptor protein TRADD to bind to the death domain, serving as a platform for subsequent protein binding. Following TRADD binding, three pathways can be initiated.

- Activation of NF-κB: TRADD recruits TRAF2 and RIP. TRAF2 in turn recruits the multicomponent protein kinase IKK, enabling the serine-threonine kinase RIP to activate it. An inhibitory protein, IκBα, that normally binds to NF-κB and inhibits its translocation, is phosphorylated by IKK and subsequently degraded, releasing NF-κB. NF-κB is a heterodimeric transcription factor that translocates to the nucleus and mediates the transcription of a vast array of proteins involved in cell survival and proliferation, inflammatory response, and anti-apoptotic factors.

- Activation of the MAPK pathways: Of the three major MAPK cascades, TNF induces a strong activation of the stress-related JNK group, evokes moderate response of the p38-MAPK, and is responsible for minimal activation of the classical ERKs. TRAF2/Rac activates the JNK-inducing upstream kinases of MLK2/MLK3, TAK1, MEKK1 and ASK1 (either directly or through GCKs and Trx, respectively). SRC- Vav- Rac axis activates MLK2/MLK3 and these kinases phosphorylate MKK7, which then activates JNK. JNK translocates to the nucleus and activates transcription factors such as c-Jun and ATF2. The JNK pathway is involved in cell differentiation, proliferation, and is generally pro-apoptotic.

- Induction of death signaling: Like all death-domain-containing members of the TNFR superfamily, TNFR1 is involved in death signaling. However, TNF-induced cell death plays only a minor role compared to its overwhelming functions in the inflammatory process. Its death-inducing capability is weak compared to other family members (such as Fas), and often masked by the anti-apoptotic effects of NF-κB. Nevertheless, TRADD binds FADD, which then recruits the cysteine protease caspase-8. A high concentration of caspase-8 induces its autoproteolytic activation and subsequent cleaving of effector caspases, leading to cell apoptosis.

The myriad and often-conflicting effects mediated by the above pathways indicate the existence of extensive cross-talk. For instance, NF-κB enhances the transcription of C-FLIP, Bcl-2, and cIAP1 / cIAP2, inhibitory proteins that interfere with death signaling. On the other hand, activated caspases cleave several components of the NF-κB pathway, including RIP, IKK, and the subunits of NF-κB itself. Other factors, such as cell type, concurrent stimulation of other cytokines, or the amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can shift the balance in favor of one pathway or another. Such complicated signaling ensures that, whenever TNF is released, various cells with vastly diverse functions and conditions can all respond appropriately to inflammation. Both protein molecules tumor necrosis factor alpha and keratin 17 appear to be related in case of oral submucous fibrosis

In animal models TNF selectively kills autoreactive T cells.

There is also evidence that TNF-α signaling triggers downstream epigenetic modifications that result in lasting enhancement of pro-inflammatory responses in cells.

Enzyme regulation

This protein may use the morpheein model of allosteric regulation.

Clinical significance

TNF was thought to be produced primarily by macrophages, but it is produced also by a broad variety of cell types including lymphoid cells, mast cells, endothelial cells, cardiac myocytes, adipose tissue, fibroblasts, and neurons. Large amounts of TNF are released in response to lipopolysaccharide, other bacterial products, and interleukin-1 (IL-1). In the skin, mast cells appear to be the predominant source of pre-formed TNF, which can be released upon inflammatory stimulus (e.g., LPS).

It has a number of actions on various organ systems, generally together with IL-1 and interleukin-6 (IL-6):

- On the hypothalamus:

- Stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis by stimulating the release of corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH)

- Suppressing appetite

- Fever

- On the liver: stimulating the acute phase response, leading to an increase in C-reactive protein and a number of other mediators. It also induces insulin resistance by promoting serine-phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), which impairs insulin signaling

- It is a potent chemoattractant for neutrophils, and promotes the expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells, helping neutrophils migrate.

- On macrophages: stimulates phagocytosis, and production of IL-1 oxidants and the inflammatory lipid prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)

- On other tissues: increasing insulin resistance. TNF phosphorylates insulin receptor serine residues, blocking signal transduction.

- On metabolism and food intake: regulates bitter taste perception.

A local increase in concentration of TNF will cause the cardinal signs of Inflammation to occur: heat, swelling, redness, pain and loss of function.

Whereas high concentrations of TNF induce shock-like symptoms, the prolonged exposure to low concentrations of TNF can result in cachexia, a wasting syndrome. This can be found, for example, in cancer patients.

Said et al. showed that TNF causes an IL-10-dependent inhibition of CD4 T-cell expansion and function by up-regulating PD-1 levels on monocytes which leads to IL-10 production by monocytes after binding of PD-1 by PD-L.

The research of Pedersen et al. indicates that TNF increase in response to sepsis is inhibited by the exercise-induced production of myokines. To study whether acute exercise induces a true anti-inflammatory response, a model of 'low grade inflammation' was established in which a low dose of E. coli endotoxin was administered to healthy volunteers, who had been randomised to either rest or exercise prior to endotoxin administration. In resting subjects, endotoxin induced a 2- to 3-fold increase in circulating levels of TNF. In contrast, when the subjects performed 3 hours of ergometer cycling and received the endotoxin bolus at 2.5 h, the TNF response was totally blunted. This study provides some evidence that acute exercise may inhibit TNF production.

In the brain TNF can protect against excitotoxicity. TNF strengthens synapses. TNF in neurons promotes their survival, whereas TNF in macrophages and microglia results in neurotoxins that induce apoptosis.

TNF-α and IL-6 concentrations are elevated in obesity. Monoclonal antibody against TNF-α is associated with increases rather than decreases in obesity, indicating that inflammation is the result, rather than the cause, of obesity. TNF and IL-6 are the most prominent cytokines predicting COVID-19 severity and death.

Pharmacology

TNF promotes the inflammatory response, which, in turn, causes many of the clinical problems associated with autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa and refractory asthma. These disorders are sometimes treated by using a TNF inhibitor. This inhibition can be achieved with a monoclonal antibody such as infliximab (Remicade) binding directly to TNF, adalimumab (Humira), certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) or with a decoy circulating receptor fusion protein such as etanercept (Enbrel) which binds to TNF with greater affinity than the TNFR.

On the other hand, some patients treated with TNF inhibitors develop an aggravation of their disease or new onset of autoimmunity. TNF seems to have an immunosuppressive facet as well. One explanation for a possible mechanism is this observation that TNF has a positive effect on regulatory T cells (Tregs), due to its binding to the tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2).

Anti-TNF therapy has shown only modest effects in cancer therapy. Treatment of renal cell carcinoma with infliximab resulted in prolonged disease stabilization in certain patients. Etanercept was tested for treating patients with breast cancer and ovarian cancer showing prolonged disease stabilization in certain patients via downregulation of IL-6 and CCL2. On the other hand, adding infliximab or etanercept to gemcitabine for treating patients with advanced pancreatic cancer was not associated with differences in efficacy when compared with placebo.

Interactions

TNF has been shown to interact with TNFRSF1A.