The Scientific Revolution was a series of events in which that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transformed the views of society about nature.[1][2][3][4][5][6] The Scientific Revolution took place in Europe towards the end of the Renaissance period and continued through the late 18th century, influencing the intellectual social movement known as the Enlightenment. While its dates are debated, the publication in 1543 of Nicolaus Copernicus's De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) is often cited as marking the beginning of the Scientific Revolution.

The concept of a scientific revolution taking place over an extended period emerged in the eighteenth century in the work of Jean Sylvain Bailly, who saw a two-stage process of sweeping away the old and establishing the new.[7] The beginning of the Scientific Revolution, the Scientific Renaissance, was focused on the recovery of the knowledge of the ancients; this is generally considered to have ended in 1632 with publication of Galileo's Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems.[8] The completion of the Scientific Revolution is attributed to the "grand synthesis" of Isaac Newton's 1687 Principia. The work formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation thereby completing the synthesis of a new cosmology.[9] By the end of the 18th century, the Scientific Revolution had given way to the "Age of Reflection."

The concept of a scientific revolution taking place over an extended period emerged in the eighteenth century in the work of Jean Sylvain Bailly, who saw a two-stage process of sweeping away the old and establishing the new.[7] The beginning of the Scientific Revolution, the Scientific Renaissance, was focused on the recovery of the knowledge of the ancients; this is generally considered to have ended in 1632 with publication of Galileo's Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems.[8] The completion of the Scientific Revolution is attributed to the "grand synthesis" of Isaac Newton's 1687 Principia. The work formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation thereby completing the synthesis of a new cosmology.[9] By the end of the 18th century, the Scientific Revolution had given way to the "Age of Reflection."

Introduction

Great advances in science have been termed "revolutions" since the 18th century. In 1747, Clairaut wrote that "Newton was said in his own lifetime to have created a revolution".[10] The word was also used in the preface to Lavoisier's 1789 work announcing the discovery of oxygen. "Few revolutions in science have immediately excited so much general notice as the introduction of the theory of oxygen ... Lavoisier saw his theory accepted by all the most eminent men of his time, and established over a great part of Europe within a few years from its first promulgation."[11]In the 19th century, William Whewell described the revolution in science itself—the scientific method—that had taken place in the 15th–16th century. "Among the most conspicuous of the revolutions which opinions on this subject have undergone, is the transition from an implicit trust in the internal powers of man's mind to a professed dependence upon external observation; and from an unbounded reverence for the wisdom of the past, to a fervid expectation of change and improvement."[12] This gave rise to the common view of the Scientific Revolution today:

- "A new view of nature emerged, replacing the Greek view that had dominated science for almost 2,000 years. Science became an autonomous discipline, distinct from both philosophy and technology and came to be regarded as having utilitarian goals."[13]

Portrait of Galileo Galilei by Leoni

The Scientific Revolution is traditionally assumed to start with the Copernican Revolution (initiated in 1543) and to be complete in the "grand synthesis" of Isaac Newton's 1687 Principia. Much of the change of attitude came from Francis Bacon whose "confident and emphatic announcement" in the modern progress of science inspired the creation of scientific societies such as the Royal Society, and Galileo who championed Copernicus and developed the science of motion.

In the 20th century, Alexandre Koyré introduced the term "scientific revolution", centering his analysis on Galileo. The term was popularized by Butterfield in his Origins of Modern Science. Thomas Kuhn's 1962 work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions emphasized that different theoretical frameworks—such as Einstein's relativity theory and Newton's theory of gravity, which it replaced—cannot be directly compared.

Significance

The period saw a fundamental transformation in scientific ideas across mathematics, physics, astronomy, and biology in institutions supporting scientific investigation and in the more widely held picture of the universe. The Scientific Revolution led to the establishment of several modern sciences. In 1984, Joseph Ben-David wrote:Rapid accumulation of knowledge, which has characterized the development of science since the 17th century, had never occurred before that time. The new kind of scientific activity emerged only in a few countries of Western Europe, and it was restricted to that small area for about two hundred years. (Since the 19th century, scientific knowledge has been assimilated by the rest of the world).[14]Many contemporary writers and modern historians claim that there was a revolutionary change in world view. In 1611 the English poet, John Donne, wrote:

[The] new Philosophy calls all in doubt,Mid-20th-century historian Herbert Butterfield was less disconcerted, but nevertheless saw the change as fundamental:

The Element of fire is quite put out;

The Sun is lost, and th'earth, and no man's wit

Can well direct him where to look for it.[15]

Since that revolution turned the authority in English not only of the Middle Ages but of the ancient world—since it started not only in the eclipse of scholastic philosophy but in the destruction of Aristotelian physics—it outshines everything since the rise of Christianity and reduces the Renaissance and Reformation to the rank of mere episodes, mere internal displacements within the system of medieval Christendom.... [It] looms so large as the real origin both of the modern world and of the modern mentality that our customary periodization of European history has become an anachronism and an encumbrance.[16]The history professor Peter Harrison attributes Christianity to having contributed to the rise of the Scientific Revolution:

historians of science have long known that religious factors played a significantly positive role in the emergence and persistence of modern science in the West. Not only were many of the key figures in the rise of science individuals with sincere religious commitments, but the new approaches to nature that they pioneered were underpinned in various ways by religious assumptions. ... Yet, many of the leading figures in the scientific revolution imagined themselves to be champions of a science that was more compatible with Christianity than the medieval ideas about the natural world that they replaced.[17]

Ancient and medieval background

Ptolemaic model of the spheres for Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Georg von Peuerbach, Theoricae novae planetarum, 1474.

The Scientific Revolution was built upon the foundation of ancient Greek learning and science in the Middle Ages, as it had been elaborated and further developed by Roman/Byzantine science and medieval Islamic science.[6] Some scholars have noted a direct tie between "particular aspects of traditional Christianity" and the rise of science.[18][19] The "Aristotelian tradition" was still an important intellectual framework in the 17th century, although by that time natural philosophers had moved away from much of it.[5] Key scientific ideas dating back to classical antiquity had changed drastically over the years, and in many cases been discredited.[5] The ideas that remained, which were transformed fundamentally during the Scientific Revolution, include:

- Aristotle's cosmetics that placed the Earth at the center of a spherical hierarchic cosmos. The terrestrial and celestial regions were made up of different elements which had different kinds of natural movement.

- The terrestrial region, according to Aristotle, consisted of concentric spheres of the four elements—earth, water, air, and fire. All bodies naturally moved in straight lines until they reached the sphere appropriate to their elemental composition—their natural place. All other terrestrial motions were non-natural, or violent.[20][21]

- The celestial region was made up of the fifth element, aether, which was unchanging and moved naturally with uniform circular motion.[22] In the Aristotelian tradition, astronomical theories sought to explain the observed irregular motion of celestial objects through the combined effects of multiple uniform circular motions.[23]

- The Ptolemaic model of planetary motion: based on the geometrical model of Eudoxus of Cnidus, Ptolemy's Almagest, demonstrated that calculations could compute the exact positions of the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets in the future and in the past, and showed how these computational models were derived from astronomical observations. As such they formed the model for later astronomical developments. The physical basis for Ptolemaic models invoked layers of spherical shells, though the most complex models were inconsistent with this physical explanation.[24]

It is also true that many of the important figures of the Scientific Revolution shared in the general Renaissance respect for ancient learning and cited ancient pedigrees for their innovations. Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543),[25] Galileo Galilei (1564–1642),[1][2][3][26] Kepler (1571–1630)[27] and Newton (1642–1727),[28] all traced different ancient and medieval ancestries for the heliocentric system. In the Axioms Scholium of his Principia, Newton said its axiomatic three laws of motion were already accepted by mathematicians such as Huygens (1629–1695), Wallace, Wren and others. While preparing a revised edition of his Principia, Newton attributed his law of gravity and his first law of motion to a range of historical figures.[28][29]

Despite these qualifications, the standard theory of the history of the Scientific Revolution claims that the 17th century was a period of revolutionary scientific changes. Not only were there revolutionary theoretical and experimental developments, but that even more importantly, the way in which scientists worked was radically changed. For instance, although intimations of the concept of inertia are suggested sporadically in ancient discussion of motion,[30][31] the salient point is that Newton's theory differed from ancient understandings in key ways, such as an external force being a requirement for violent motion in Aristotle's theory.[32]

Scientific method

Under the scientific method as conceived in the 17th century, natural and artificial circumstances were set aside as a research tradition of systematic experimentation was slowly accepted by the scientific community. The philosophy of using an inductive approach to obtain knowledge — to abandon assumption and to attempt to observe with an open mind — was in contrast with the earlier, Aristotelian approach of deduction, by which analysis of known facts produced further understanding. In practice, many scientists and philosophers believed that a healthy mix of both was needed — the willingness to question assumptions, yet also to interpret observations assumed to have some degree of validity.By the end of the Scientific Revolution the qualitative world of book-reading philosophers had been changed into a mechanical, mathematical world to be known through experimental research. Though it is certainly not true that Newtonian science was like modern science in all respects, it conceptually resembled ours in many ways. Many of the hallmarks of modern science, especially with regard to its institutionalization and professionalization, did not become standard until the mid-19th century.

Empiricism

The Aristotelian scientific tradition's primary mode of interacting with the world was through observation and searching for "natural" circumstances through reasoning. Coupled with this approach was the belief that rare events which seemed to contradict theoretical models were aberrations, telling nothing about nature as it "naturally" was. During the Scientific Revolution, changing perceptions about the role of the scientist in respect to nature, the value of evidence, experimental or observed, led towards a scientific methodology in which empiricism played a large, but not absolute, role.By the start of the Scientific Revolution, empiricism had already become an important component of science and natural philosophy. Prior thinkers, including the early 14th century nominalist philosopher William of Ockham, had begun the intellectual movement toward empiricism.[33]

The term British empiricism came into use to describe philosophical differences perceived between two of its founders Francis Bacon, described as empiricist, and René Descartes, who was described as a rationalist. Thomas Hobbes, George Berkeley, and David Hume were the philosophy's primary exponents, who developed a sophisticated empirical tradition as the basis of human knowledge.

An influential formulation of empiricism was John Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), in which he maintained that the only true knowledge that could be accessible to the human mind was that which was based on experience. He wrote that the human mind was created as a tabula rasa, a "blank tablet," upon which sensory impressions were recorded and built up knowledge through a process of reflection.

Baconian science

Francis Bacon was a pivotal figure in establishing the scientific method of investigation. Portrait by Frans Pourbus the Younger (1617).

The philosophical underpinnings of the Scientific Revolution were laid out by Francis Bacon, who has been called the father of empiricism.[34] His works established and popularised inductive methodologies for scientific inquiry, often called the Baconian method, or simply the scientific method. His demand for a planned procedure of investigating all things natural marked a new turn in the rhetorical and theoretical framework for science, much of which still surrounds conceptions of proper methodology today.

Bacon proposed a great reformation of all process of knowledge for the advancement of learning divine and human, which he called Instauratio Magna (The Great Instauration). For Bacon, this reformation would lead to a great advancement in science and a progeny of new inventions that would relieve mankind's miseries and needs. His Novum Organum was published in 1620. He argued that man is "the minister and interpreter of nature", that "knowledge and human power are synonymous", that "effects are produced by the means of instruments and helps", and that "man while operating can only apply or withdraw natural bodies; nature internally performs the rest", and later that "nature can only be commanded by obeying her".[35] Here is an abstract of the philosophy of this work, that by the knowledge of nature and the using of instruments, man can govern or direct the natural work of nature to produce definite results. Therefore, that man, by seeking knowledge of nature, can reach power over it – and thus reestablish the "Empire of Man over creation", which had been lost by the Fall together with man's original purity. In this way, he believed, would mankind be raised above conditions of helplessness, poverty and misery, while coming into a condition of peace, prosperity and security.[36]

For this purpose of obtaining knowledge of and power over nature, Bacon outlined in this work a new system of logic he believed to be superior to the old ways of syllogism, developing his scientific method, consisting of procedures for isolating the formal cause of a phenomenon (heat, for example) through eliminative induction. For him, the philosopher should proceed through inductive reasoning from fact to axiom to physical law. Before beginning this induction, though, the enquirer must free his or her mind from certain false notions or tendencies which distort the truth. In particular, he found that philosophy was too preoccupied with words, particularly discourse and debate, rather than actually observing the material world: "For while men believe their reason governs words, in fact, words turn back and reflect their power upon the understanding, and so render philosophy and science sophistical and inactive."[37]

Bacon considered that it is of greatest importance to science not to keep doing intellectual discussions or seeking merely contemplative aims, but that it should work for the bettering of mankind's life by bringing forth new inventions, having even stated that "inventions are also, as it were, new creations and imitations of divine works".[35][page needed] He explored the far-reaching and world-changing character of inventions, such as the printing press, gunpowder and the compass.

Scientific experimentation

Bacon first described the experimental method.There remains simple experience; which, if taken as it comes, is called accident, if sought for, experiment. The true method of experience first lights the candle [hypothesis], and then by means of the candle shows the way [arranges and delimits the experiment]; commencing as it does with experience duly ordered and digested, not bungling or erratic, and from it deducing axioms [theories], and from established axioms again new experiments.William Gilbert was an early advocate of this method. He passionately rejected both the prevailing Aristotelian philosophy and the Scholastic method of university teaching. His book De Magnete was written in 1600, and he is regarded by some as the father of electricity and magnetism.[39] In this work, he describes many of his experiments with his model Earth called the terrella. From these experiments, he concluded that the Earth was itself magnetic and that this was the reason compasses point north.

— Francis Bacon. Novum Organum. 1620.[38]

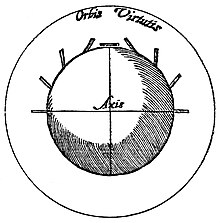

Diagram from William Gilbert's De Magnete, a pioneering work of experimental science

De Magnete was influential not only because of the inherent interest of its subject matter, but also for the rigorous way in which Gilbert described his experiments and his rejection of ancient theories of magnetism.[40] According to Thomas Thomson, "Gilbert['s]... book on magnetism published in 1600, is one of the finest examples of inductive philosophy that has ever been presented to the world. It is the more remarkable, because it preceded the Novum Organum of Bacon, in which the inductive method of philosophizing was first explained."[41]

Galileo Galilei has been called the "father of modern observational astronomy",[42] the "father of modern physics",[43][44] the "father of science",[44][45] and "the Father of Modern Science".[46] His original contributions to the science of motion were made through an innovative combination of experiment and mathematics.[47]

On this page Galileo Galilei first noted the moons of Jupiter. Galileo revolutionized the study of the natural world with his rigorous experimental method.

Galileo was one of the first modern thinkers to clearly state that the laws of nature are mathematical. In The Assayer he wrote "Philosophy is written in this grand book, the universe ... It is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometric figures;...."[48] His mathematical analyses are a further development of a tradition employed by late scholastic natural philosophers, which Galileo learned when he studied philosophy.[49] He ignored Aristotelianism. In broader terms, his work marked another step towards the eventual separation of science from both philosophy and religion; a major development in human thought. He was often willing to change his views in accordance with observation. In order to perform his experiments, Galileo had to set up standards of length and time, so that measurements made on different days and in different laboratories could be compared in a reproducible fashion. This provided a reliable foundation on which to confirm mathematical laws using inductive reasoning.

Galileo showed an appreciation for the relationship between mathematics, theoretical physics, and experimental physics. He understood the parabola, both in terms of conic sections and in terms of the ordinate (y) varying as the square of the abscissa (x). Galilei further asserted that the parabola was the theoretically ideal trajectory of a uniformly accelerated projectile in the absence of friction and other disturbances. He conceded that there are limits to the validity of this theory, noting on theoretical grounds that a projectile trajectory of a size comparable to that of the Earth could not possibly be a parabola,[50] but he nevertheless maintained that for distances up to the range of the artillery of his day, the deviation of a projectile's trajectory from a parabola would be only very slight.[51][52]

Mathematization

Scientific knowledge, according to the Aristotelians, was concerned with establishing true and necessary causes of things.[53] To the extent that medieval natural philosophers used mathematical problems, they limited social studies to theoretical analyses of local speed and other aspects of life.[54] The actual measurement of a physical quantity, and the comparison of that measurement to a value computed on the basis of theory, was largely limited to the mathematical disciplines of astronomy and optics in Europe.[55][56]In the 16th and 17th centuries, European scientists began increasingly applying quantitative measurements to the measurement of physical phenomena on the Earth. Galileo maintained strongly that mathematics provided a kind of necessary certainty that could be compared to God's: "...with regard to those few [mathematical propositions] which the human intellect does understand, I believe its knowledge equals the Divine in objective certainty..."[57]

Galileo anticipates the concept of a systematic mathematical interpretation of the world in his book Il Saggiatore:

Philosophy [i.e., physics] is written in this grand book—I mean the universe—which stands continually open to our gaze, but it cannot be understood unless one first learns to comprehend the language and interpret the characters in which it is written. It is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometrical figures, without which it is humanly impossible to understand a single word of it; without these, one is wandering around in a dark labyrinth.[58]

The mechanical philosophy

Isaac Newton in a 1702 portrait by Godfrey Kneller

Aristotle recognized four kinds of causes, and where applicable, the most important of them is the "final cause". The final cause was the aim, goal, or purpose of some natural process or man-made thing. Until the Scientific Revolution, it was very natural to see such aims, such as a child's growth, for example, leading to a mature adult. Intelligence was assumed only in the purpose of man-made artifacts; it was not attributed to other animals or to nature.

In "mechanical philosophy" no field or action at a distance is permitted, particles or corpuscles of matter are fundamentally inert. Motion is caused by direct physical collision. Where natural substances had previously been understood organically, the mechanical philosophers viewed them as machines.[59] As a result, Isaac Newton's theory seemed like some kind of throwback to "spooky action at a distance". According to Thomas Kuhn, Newton and Descartes held the teleological principle that God conserved the amount of motion in the universe:

Gravity, interpreted as an innate attraction between every pair of particles of matter, was an occult quality in the same sense as the scholastics' "tendency to fall" had been.... By the mid eighteenth century that interpretation had been almost universally accepted, and the result was a genuine reversion (which is not the same as a retrogression) to a scholastic standard. Innate attractions and repulsions joined size, shape, position and motion as physically irreducible primary properties of matter.[60]Newton had also specifically attributed the inherent power of inertia to matter, against the mechanist thesis that matter has no inherent powers. But whereas Newton vehemently denied gravity was an inherent power of matter, his collaborator Roger Cotes made gravity also an inherent power of matter, as set out in his famous preface to the Principia's 1713 second edition which he edited, and contradicted Newton himself. And it was Cotes's interpretation of gravity rather than Newton's that came to be accepted.

Institutionalization

The Royal Society had its origins in Gresham College, and was the first scientific society in the world.

The first moves towards the institutionalization of scientific investigation and dissemination took the form of the establishment of societies, where new discoveries were aired, discussed and published. The first scientific society to be established was the Royal Society of London. This grew out of an earlier group, centred around Gresham College in the 1640s and 1650s. According to a history of the College:

The scientific network which centred on Gresham College played a crucial part in the meetings which led to the formation of the Royal Society.[61]These physicians and natural philosophers were influenced by the "new science", as promoted by Francis Bacon in his New Atlantis, from approximately 1645 onwards. A group known as The Philosophical Society of Oxford was run under a set of rules still retained by the Bodleian Library.[62]

On 28 November 1660, the 1660 committee of 12 announced the formation of a "College for the Promoting of Physico-Mathematical Experimental Learning", which would meet weekly to discuss science and run experiments. At the second meeting, Robert Moray announced that the King approved of the gatherings, and a Royal charter was signed on 15 July 1662 creating the "Royal Society of London", with Lord Brouncker serving as the first President. A second Royal Charter was signed on 23 April 1663, with the King noted as the Founder and with the name of "the Royal Society of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge"; Robert Hooke was appointed as Curator of Experiments in November. This initial royal favour has continued, and since then every monarch has been the patron of the Society.[63]

The French Academy of Sciences was established in 1666.

The Society's first Secretary was Henry Oldenburg. Its early meetings included experiments performed first by Robert Hooke and then by Denis Papin, who was appointed in 1684. These experiments varied in their subject area, and were both important in some cases and trivial in others.[64] The society began publication of Philosophical Transactions from 1665, the oldest and longest-running scientific journal in the world, which established the important principles of scientific priority and peer review.[65]

The French established the Academy of Sciences in 1666. In contrast to the private origins of its British counterpart, the Academy was founded as a government body by Jean-Baptiste Colbert. Its rules were set down in 1699 by King Louis XIV, when it received the name of 'Royal Academy of Sciences' and was installed in the Louvre in Paris.

New ideas

As the Scientific Revolution was not marked by any single change, the following new ideas contributed to what is called the Scientific Revolution. Many of them were revolutions in their own fields.Astronomy

- Heliocentrism

Portrait of Johannes Kepler

Copernicus' 1543 work on the heliocentric model of the solar system tried to demonstrate that the sun was the center of the universe. Few were bothered by this suggestion, and the pope and several archbishops were interested enough by it to want more detail.[67] His model was later used to create the calendar of Pope Gregory XIII.[68] However, the idea that the earth moved around the sun was doubted by most of Copernicus' contemporaries. It contradicted not only empirical observation, due to the absence of an observable stellar parallax,[69] but more significantly at the time, the authority of Aristotle.

The discoveries of Johannes Kepler and Galileo gave the theory credibility. Kepler was an astronomer who, using the accurate observations of Tycho Brahe, proposed that the planets move around the sun not in circular orbits, but in elliptical ones. Together with his other laws of planetary motion, this allowed him to create a model of the solar system that was an improvement over Copernicus' original system. Galileo's main contributions to the acceptance of the heliocentric system were his mechanics, the observations he made with his telescope, as well as his detailed presentation of the case for the system. Using an early theory of inertia, Galileo could explain why rocks dropped from a tower fall straight down even if the earth rotates. His observations of the moons of Jupiter, the phases of Venus, the spots on the sun, and mountains on the moon all helped to discredit the Aristotelian philosophy and the Ptolemaic theory of the solar system. Through their combined discoveries, the heliocentric system gained support, and at the end of the 17th century it was generally accepted by astronomers.

This work culminated in the work of Isaac Newton. Newton's Principia formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation, which dominated scientists' view of the physical universe for the next three centuries. By deriving Kepler's laws of planetary motion from his mathematical description of gravity, and then using the same principles to account for the trajectories of comets, the tides, the precession of the equinoxes, and other phenomena, Newton removed the last doubts about the validity of the heliocentric model of the cosmos. This work also demonstrated that the motion of objects on Earth and of celestial bodies could be described by the same principles. His prediction that the Earth should be shaped as an oblate spheroid was later vindicated by other scientists. His laws of motion were to be the solid foundation of mechanics; his law of universal gravitation combined terrestrial and celestial mechanics into one great system that seemed to be able to describe the whole world in mathematical formulae.

- Gravitation

Isaac Newton's Principia, developed the first set of unified scientific laws.

As well as proving the heliocentric model, Newton also developed the theory of gravitation. In 1679, Newton began to consider gravitation and its effect on the orbits of planets with reference to Kepler's laws of planetary motion. This followed stimulation by a brief exchange of letters in 1679–80 with Robert Hooke, who had been appointed to manage the Royal Society's correspondence, and who opened a correspondence intended to elicit contributions from Newton to Royal Society transactions.[70] Newton's reawakening interest in astronomical matters received further stimulus by the appearance of a comet in the winter of 1680–1681, on which he corresponded with John Flamsteed.[71] After the exchanges with Hooke, Newton worked out proof that the elliptical form of planetary orbits would result from a centripetal force inversely proportional to the square of the radius vector (see Newton's law of universal gravitation – History and De motu corporum in gyrum). Newton communicated his results to Edmond Halley and to the Royal Society in De motu corporum in gyrum, in 1684.[72] This tract contained the nucleus that Newton developed and expanded to form the Principia.[73]

The Principia was published on 5 July 1687 with encouragement and financial help from Edmond Halley.[74] In this work, Newton stated the three universal laws of motion that contributed to many advances during the Industrial Revolution which soon followed and were not to be improved upon for more than 200 years. Many of these advancements continue to be the underpinnings of non-relativistic technologies in the modern world. He used the Latin word gravitas (weight) for the effect that would become known as gravity, and defined the law of universal gravitation.

Newton's postulate of an invisible force able to act over vast distances led to him being criticised for introducing "occult agencies" into science.[75] Later, in the second edition of the Principia (1713), Newton firmly rejected such criticisms in a concluding General Scholium, writing that it was enough that the phenomena implied a gravitational attraction, as they did; but they did not so far indicate its cause, and it was both unnecessary and improper to frame hypotheses of things that were not implied by the phenomena. (Here Newton used what became his famous expression "hypotheses non fingo"[76]).

Biology and Medicine

- Medical discoveries

The writings of Greek physician Galen had dominated European medical thinking for over a millennium. The Flemish scholar Vesalius demonstrated mistakes in the Galen's ideas. Vesalius dissected human corpses, whereas Galen dissected animal corpses. Published in 1543, Vesalius' De humani corporis fabrica[77] was a groundbreaking work of human anatomy. It emphasized the priority of dissection and what has come to be called the "anatomical" view of the body, seeing human internal functioning as an essentially corporeal structure filled with organs arranged in three-dimensional space. This was in stark contrast to many of the anatomical models used previously, which had strong Galenic/Aristotelean elements, as well as elements of astrology.

Besides the first good description of the sphenoid bone, he showed that the sternum consists of three portions and the sacrum of five or six; and described accurately the vestibule in the interior of the temporal bone. He not only verified the observation of Etienne on the valves of the hepatic veins, but he described the vena azygos, and discovered the canal which passes in the fetus between the umbilical vein and the vena cava, since named ductus venosus. He described the omentum, and its connections with the stomach, the spleen and the colon; gave the first correct views of the structure of the pylorus; observed the small size of the caecal appendix in man; gave the first good account of the mediastinum and pleura and the fullest description of the anatomy of the brain yet advanced. He did not understand the inferior recesses; and his account of the nerves is confused by regarding the optic as the first pair, the third as the fifth and the fifth as the seventh.

Further groundbreaking work was carried out by William Harvey, who published De Motu Cordis in 1628. Harvey made a detailed analysis of the overall structure of the heart, going on to an analysis of the arteries, showing how their pulsation depends upon the contraction of the left ventricle, while the contraction of the right ventricle propels its charge of blood into the pulmonary artery. He noticed that the two ventricles move together almost simultaneously and not independently like had been thought previously by his predecessors.[78]

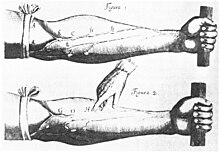

Image of veins from William Harvey's Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus. Harvey demonstrated that blood circulated around the body, rather than being created in the liver.

In the eighth chapter, Harvey estimated the capacity of the heart, how much blood is expelled through each pump of the heart, and the number of times the heart beats in a half an hour. From these estimations, he demonstrated that according to Gaelen's theory that blood was continually produced in the liver, the absurdly large figure of 540 pounds of blood would have to be produced every day. Having this simple mathematical proportion at hand – which would imply a seemingly impossible role for the liver – Harvey went on to demonstrate how the blood circulated in a circle by means of countless experiments initially done on serpents and fish: tying their veins and arteries in separate periods of time, Harvey noticed the modifications which occurred; indeed, as he tied the veins, the heart would become empty, while as he did the same to the arteries, the organ would swell up.

This process was later performed on the human body (in the image on the left): the physician tied a tight ligature onto the upper arm of a person. This would cut off blood flow from the arteries and the veins. When this was done, the arm below the ligature was cool and pale, while above the ligature it was warm and swollen. The ligature was loosened slightly, which allowed blood from the arteries to come into the arm, since arteries are deeper in the flesh than the veins. When this was done, the opposite effect was seen in the lower arm. It was now warm and swollen. The veins were also more visible, since now they were full of blood.

Various other advances in medical understanding and practice were made. French physician Pierre Fauchard started dentistry science as we know it today, and he has been named "the father of modern dentistry". Surgeon Ambroise Paré (c.1510–1590) was a leader in surgical techniques and battlefield medicine, especially the treatment of wounds,[79] and Herman Boerhaave (1668–1738) is sometimes referred to as a "father of physiology" due to his exemplary teaching in Leiden and his textbook Institutiones medicae (1708).

Chemistry

Title page from The Sceptical Chymist, a foundational text of chemistry, written by Robert Boyle in 1661

Chemistry, and its antecedent alchemy, became an increasingly important aspect of scientific thought in the course of the 16th and 17th centuries. The importance of chemistry is indicated by the range of important scholars who actively engaged in chemical research. Among them were the astronomer Tycho Brahe,[80] the chemical physician Paracelsus, Robert Boyle, Thomas Browne and Isaac Newton. Unlike the mechanical philosophy, the chemical philosophy stressed the active powers of matter, which alchemists frequently expressed in terms of vital or active principles—of spirits operating in nature.[81]

Practical attempts to improve the refining of ores and their extraction to smelt metals was an important source of information for early chemists in the 16th century, among them Georg Agricola (1494–1555), who published his great work De re metallica in 1556.[82] His work describes the highly developed and complex processes of mining metal ores, metal extraction and metallurgy of the time. His approach removed the mysticism associated with the subject, creating the practical base upon which others could build.[83]

English chemist Robert Boyle (1627–1691) is considered to have refined the modern scientific method for alchemy and to have separated chemistry further from alchemy.[84] Although his research clearly has its roots in the alchemical tradition, Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of modern chemistry, and one of the pioneers of modern experimental scientific method. Although Boyle was not the original discover, he is best known for Boyle's law, which he presented in 1662:[85] the law describes the inversely proportional relationship between the absolute pressure and volume of a gas, if the temperature is kept constant within a closed system.[86]

Boyle is also credited for his landmark publication The Sceptical Chymist in 1661, which is seen as a cornerstone book in the field of chemistry. In the work, Boyle presents his hypothesis that every phenomenon was the result of collisions of particles in motion. Boyle appealed to chemists to experiment and asserted that experiments denied the limiting of chemical elements to only the classic four: earth, fire, air, and water. He also pleaded that chemistry should cease to be subservient to medicine or to alchemy, and rise to the status of a science. Importantly, he advocated a rigorous approach to scientific experiment: he believed all theories must be tested experimentally before being regarded as true. The work contains some of the earliest modern ideas of atoms, molecules, and chemical reaction, and marks the beginning of the history of modern chemistry.

Physical

- Optics

Newton's Opticks or a treatise of the reflections, refractions, inflections and colours of light

Important work was done in the field of optics. Johannes Kepler published Astronomiae Pars Optica (The Optical Part of Astronomy) in 1604. In it, he described the inverse-square law governing the intensity of light, reflection by flat and curved mirrors, and principles of pinhole cameras, as well as the astronomical implications of optics such as parallax and the apparent sizes of heavenly bodies. Astronomiae Pars Optica is generally recognized as the foundation of modern optics (though the law of refraction is conspicuously absent).[87]

Willebrord Snellius (1580–1626) found the mathematical law of refraction, now known as Snell's law, in 1621. Subsequently René Descartes (1596–1650) showed, by using geometric construction and the law of refraction (also known as Descartes' law), that the angular radius of a rainbow is 42° (i.e. the angle subtended at the eye by the edge of the rainbow and the rainbow's centre is 42°).[88] He also independently discovered the law of reflection, and his essay on optics was the first published mention of this law.

Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) wrote several works in the area of optics. These included the Opera reliqua (also known as Christiani Hugenii Zuilichemii, dum viveret Zelhemii toparchae, opuscula posthuma) and the Traité de la lumière.

Isaac Newton investigated the refraction of light, demonstrating that a prism could decompose white light into a spectrum of colours, and that a lens and a second prism could recompose the multicoloured spectrum into white light. He also showed that the coloured light does not change its properties by separating out a coloured beam and shining it on various objects. Newton noted that regardless of whether it was reflected or scattered or transmitted, it stayed the same colour. Thus, he observed that colour is the result of objects interacting with already-coloured light rather than objects generating the colour themselves. This is known as Newton's theory of colour. From this work he concluded that any refracting telescope would suffer from the dispersion of light into colours. The interest of the Royal Society encouraged him to publish his notes On Colour (later expanded into Opticks). Newton argued that light is composed of particles or corpuscles and were refracted by accelerating toward the denser medium, but he had to associate them with waves to explain the diffraction of light.

In his Hypothesis of Light of 1675, Newton posited the existence of the ether to transmit forces between particles. In 1704, Newton published Opticks, in which he expounded his corpuscular theory of light. He considered light to be made up of extremely subtle corpuscles, that ordinary matter was made of grosser corpuscles and speculated that through a kind of alchemical transmutation "Are not gross Bodies and Light convertible into one another, ...and may not Bodies receive much of their Activity from the Particles of Light which enter their Composition?"[89]

- Electricity

Otto von Guericke's experiments on electrostatics, published 1672

Dr. William Gilbert, in De Magnete, invented the New Latin word electricus from ἤλεκτρον (elektron), the Greek word for "amber". Gilbert undertook a number of careful electrical experiments, in the course of which he discovered that many substances other than amber, such as sulphur, wax, glass, etc.,[90] were capable of manifesting electrical properties. Gilbert also discovered that a heated body lost its electricity and that moisture prevented the electrification of all bodies, due to the now well-known fact that moisture impaired the insulation of such bodies. He also noticed that electrified substances attracted all other substances indiscriminately, whereas a magnet only attracted iron. The many discoveries of this nature earned for Gilbert the title of founder of the electrical science.[91] By investigating the forces on a light metallic needle, balanced on a point, he extended the list of electric bodies, and found also that many substances, including metals and natural magnets, showed no attractive forces when rubbed. He noticed that dry weather with north or east wind was the most favourable atmospheric condition for exhibiting electric phenomena—an observation liable to misconception until the difference between conductor and insulator was understood.[92]

Robert Boyle also worked frequently at the new science of electricity, and added several substances to Gilbert's list of electrics. He left a detailed account of his researches under the title of Experiments on the Origin of Electricity.[92] Boyle, in 1675, stated that electric attraction and repulsion can act across a vacuum. One of his important discoveries was that electrified bodies in a vacuum would attract light substances, this indicating that the electrical effect did not depend upon the air as a medium. He also added resin to the then known list of electrics.[90][91][93][94][95]

This was followed in 1660 by Otto von Guericke, who invented an early electrostatic generator. By the end of the 17th Century, researchers had developed practical means of generating electricity by friction with an electrostatic generator, but the development of electrostatic machines did not begin in earnest until the 18th century, when they became fundamental instruments in the studies about the new science of electricity. The first usage of the word electricity is ascribed to Sir Thomas Browne in his 1646 work, Pseudodoxia Epidemica. In 1729 Stephen Gray (1666–1736) demonstrated that electricity could be "transmitted" through metal filaments.[96]

New mechanical devices

As an aid to scientific investigation, various tools, measuring aids and calculating devices were developed in this period.Calculating devices

An ivory set of Napier's Bones, an early calculating device invented by John Napier

John Napier introduced logarithms as a powerful mathematical tool. With the help of the prominent mathematician Henry Briggs their logarithmic tables embodied a computational advance that made calculations by hand much quicker.[97] His Napier's bones used a set of numbered rods as a multiplication tool using the system of lattice multiplication. The way was opened to later scientific advances, particularly in astronomy and dynamics.

At Oxford University, Edmund Gunter built the first analog device to aid computation. The 'Gunter's scale' was a large plane scale, engraved with various scales, or lines. Natural lines, such as the line of chords, the line of sines and tangents are placed on one side of the scale and the corresponding artificial or logarithmic ones were on the other side. This calculating aid was a predecessor of the slide rule. It was William Oughtred (1575–1660) who first used two such scales sliding by one another to perform direct multiplication and division, and thus is credited as the inventor of the slide rule in 1622.

Blaise Pascal (1623–1662) invented the mechanical calculator in 1642.[98] The introduction of his Pascaline in 1645 launched the development of mechanical calculators first in Europe and then all over the world.[99][100] Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716), building on Pascal's work, became one of the most prolific inventors in the field of mechanical calculators; he was the first to describe a pinwheel calculator, in 1685,[101] and invented the Leibniz wheel, used in the arithmometer, the first mass-produced mechanical calculator. He also refined the binary number system, foundation of virtually all modern computer architectures.[102]

John Hadley (1682–1744) was the inventor of the octant, the precursor to the sextant (invented by John Bird), which greatly improved the science of navigation.

Industrial machines

The 1698 Savery Engine was the first successful steam engine

Denis Papin (1647–1712) was best known for his pioneering invention of the steam digester, the forerunner of the steam engine.[103] The first working steam engine was patented in 1698 by the inventor Thomas Savery, as a "...new invention for raising of water and occasioning motion to all sorts of mill work by the impellent force of fire, which will be of great use and advantage for drayning mines, serveing townes with water, and for the working of all sorts of mills where they have not the benefitt of water nor constant windes." [sic][104] The invention was demonstrated to the Royal Society on 14 June 1699 and the machine was described by Savery in his book The Miner's Friend; or, An Engine to Raise Water by Fire (1702),[105] in which he claimed that it could pump water out of mines. Thomas Newcomen (1664–1729) perfected the practical steam engine for pumping water, the Newcomen steam engine. Consequently, Thomas Newcomen can be regarded as a forefather of the Industrial Revolution.[106]

Abraham Darby I (1678–1717) was the first, and most famous, of three generations of the Darby family who played an important role in the Industrial Revolution. He developed a method of producing high-grade iron in a blast furnace fueled by coke rather than charcoal. This was a major step forward in the production of iron as a raw material for the Industrial Revolution.

Telescopes

Refracting telescopes first appeared in the Netherlands in 1608, apparently the product of spectacle makers experimenting with lenses. The inventor is unknown but Hans Lippershey applied for the first patent, followed by Jacob Metius of Alkmaar.[107] Galileo was one of the first scientists to use this new tool for his astronomical observations in 1609.[108]The reflecting telescope was described by James Gregory in his book Optica Promota (1663). He argued that a mirror shaped like the part of a conic section, would correct the spherical aberration that flawed the accuracy of refracting telescopes. His design, the "Gregorian telescope", however, remained un-built.

In 1666, Isaac Newton argued that the faults of the refracting telescope were fundamental because the lens refracted light of different colors differently. He concluded that light could not be refracted through a lens without causing chromatic aberrations.[109] From these experiments Newton concluded that no improvement could be made in the refracting telescope.[110] However, he was able to demonstrate that the angle of reflection remained the same for all colors, so he decided to build a reflecting telescope.[111] It was completed in 1668 and is the earliest known functional reflecting telescope.[112]

50 years later, John Hadley developed ways to make precision aspheric and parabolic objective mirrors for reflecting telescopes, building the first parabolic Newtonian telescope and a Gregorian telescope with accurately shaped mirrors.[113][114] These were successfully demonstrated to the Royal Society.[115]

Other devices

Air pump built by Robert Boyle. Many new instruments were devised in this period, which greatly aided in the expansion of scientific knowledge.

The invention of the vacuum pump paved the way for the experiments of Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke into the nature of vacuum and atmospheric pressure. The first such device was made by Otto von Guericke in 1654. It consisted of a piston and an air gun cylinder with flaps that could suck the air from any vessel that it was connected to. In 1657, he pumped the air out of two conjoined hemispheres and demonstrated that a team of sixteen horses were incapable of pulling it apart.[116] The air pump construction was greatly improved by Robert Hooke in 1658.[117]

Evangelista Torricelli (1607–1647) was best known for his invention of the mercury barometer. The motivation for the invention was to improve on the suction pumps that were used to raise water out of the mines. Torricelli constructed a sealed tube filled with mercury, set vertically into a basin of the same substance. The column of mercury fell downwards, leaving a Torricellian vacuum above.[118]

Materials, construction, and aesthetics

Surviving instruments from this period,[119][120][121][122] tend to be made of durable metals such as brass, gold, or steel, although examples such as telescopes[123] made of wood, pasteboard, or with leather components exist.[124] Those instruments that exist in collections today tend to be robust examples, made by skilled craftspeople for and at the expense of wealthy patrons.[125] These may have been commissioned as displays of wealth. In addition, the instruments preserved in collections may not have received heavy use in scientific work; instruments that had visibly received heavy use were typically destroyed, deemed unfit for display, or excluded from collections altogether.[126] It is also postulated that the scientific instruments preserved in many collections were chosen because they were more appealing to collectors, by virtue of being more ornate, more portable, or made with higher-grade materials.[127]Intact air pumps are particularly rare.[128] The pump at right included a glass sphere to permit demonstrations inside the vacuum chamber, a common use. The base was wooden, and the cylindrical pump was brass.[129] Other vacuum chambers that survived were made of brass hemispheres.[130]

Instrument makers of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century were commissioned by organizations seeking help with navigation, surveying, warfare, and astronomical observation.[128] The increase in uses for such instruments, and their widespread use in global exploration and conflict, created a need for new methods of manufacture and repair, which would be met by the Industrial Revolution.[126]

Scientific developments

People and key ideas that emerged from the 16th and 17th centuries:- First printed edition of Euclid's Elements in 1482.

- Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) published On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres in 1543, which advanced the heliocentric theory of cosmology.

- Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) published De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Structure of the Human Body) (1543), which discredited Galen's views. He found that the circulation of blood resolved from pumping of the heart. He also assembled the first human skeleton from cutting open cadavers.

- Franciscus Vieta (1540–1603) published In Artem Analycitem Isagoge (1591), which gave the first symbolic notation of parameters in literal algebra.

- William Gilbert (1544–1603) published On the Magnet and Magnetic Bodies, and on the Great Magnet the Earth in 1600, which laid the foundations of a theory of magnetism and electricity.

- Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) made extensive and more accurate naked eye observations of the planets in the late 16th century. These became the basic data for Kepler's studies.

- Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626) published Novum Organum in 1620, which outlined a new system of logic based on the process of reduction, which he offered as an improvement over Aristotle's philosophical process of syllogism. This contributed to the development of what became known as the scientific method.

- Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) improved the telescope, with which he made several important astronomical observations, including the four largest moons of Jupiter (1610), the phases of Venus (1610 - proving Copernicus correct), the rings of Saturn (1610), and made detailed observations of sunspots. He developed the laws for falling bodies based on pioneering quantitative experiments which he analyzed mathematically.

- Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) published the first two of his three laws of planetary motion in 1609.

- William Harvey (1578–1657) demonstrated that blood circulates, using dissections and other experimental techniques.

- René Descartes (1596–1650) published his Discourse on the Method in 1637, which helped to establish the scientific method.

- Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723) constructed powerful single lens microscopes and made extensive observations that he published around 1660, opening up the micro-world of biology.

- Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) published major studies of mechanics (he was the first one to correctly formulate laws concerning centrifugal force and discovered the theory of the pendulum) and optics (being one of the most influential proponents of the wave theory of light).

- Isaac Newton (1643–1727) built upon the work of Kepler, Galileo and Huygens. He showed that an inverse square law for gravity explained the elliptical orbits of the planets, and advanced the law of universal gravitation. His development of infinitesimal calculus (along with Leibniz) opened up new applications of the methods of mathematics to science. Newton taught that scientific theory should be coupled with rigorous experimentation, which became the keystone of modern science.

Criticism

Matteo Ricci (left) and Xu Guangqi (right) in Athanasius Kircher, La Chine ... Illustrée, Amsterdam, 1670.

The idea that modern science took place as a kind a revolution has been debated among historians. A weakness of the idea of scientific revolution is the lack of a systematic approach to the question of knowledge in the period comprehended between the 14th and 17th centuries, leading to misunderstandings on the value and role of modern authors. From this standpoint, the continuity thesis is the hypothesis that there was no radical discontinuity between the intellectual development of the Middle Ages and the developments in the Renaissance and early modern period and has been deeply and widely documented by the works of scholars like Pierre Duhem, John Hermann Randall, Alistair Crombie and William A. Wallace, who proved the preexistence of a wide range of ideas used by the followers of the Scientific Revolution thesis to substantiate their claims. Thus, the idea of a scientific revolution following the Renaissance is—according to the continuity thesis—a myth. Some continuity theorists point to earlier intellectual revolutions occurring in the Middle Ages, usually referring to either a European Renaissance of the 12th century[131][132] or a medieval Muslim scientific revolution,[133][134][135] as a sign of continuity.[136]

Another contrary view has been recently proposed by Arun Bala in his dialogical history of the birth of modern science. Bala proposes that the changes involved in the Scientific Revolution—the mathematical realist turn, the mechanical philosophy, the atomism, the central role assigned to the Sun in Copernican heliocentrism—have to be seen as rooted in multicultural influences on Europe. He sees specific influences in Alhazen's physical optical theory, Chinese mechanical technologies leading to the perception of the world as a machine, the Hindu-Arabic numeral system, which carried implicitly a new mode of mathematical atomic thinking, and the heliocentrism rooted in ancient Egyptian religious ideas associated with Hermeticism.[137]

Bala argues that by ignoring such multicultural impacts we have been led to a Eurocentric conception of the Scientific Revolution.[138] However, he clearly states: "The makers of the revolution – Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Descartes, Newton, and many others – had to selectively appropriate relevant ideas, transform them, and create new auxiliary concepts in order to complete their task... In the ultimate analysis, even if the revolution was rooted upon a multicultural base it is the accomplishment of Europeans in Europe."[139] Critics note that lacking documentary evidence of transmission of specific scientific ideas, Bala's model will remain "a working hypothesis, not a conclusion".[140]

A third approach takes the term "Renaissance" literally as a "rebirth". A closer study of Greek Philosophy and Greek Mathematics demonstrates that nearly all of the so-called revolutionary results of the so-called scientific revolution were in actuality restatements of ideas that were in many cases older than those of Aristotle and in nearly all cases at least as old as Archimedes. Aristotle even explicitly argues against some of the ideas that were espoused during the Scientific Revolution, such as heliocentrism. The basic ideas of the scientific method were well known to Archimedes and his contemporaries, as demonstrated in the well-known discovery of buoyancy. Atomism was first thought of by Leucippus and Democritus. Lucio Russo claims that science as a unique approach to objective knowledge was born in the Hellenistic period (c. 300 B.C), but was extinguished with the advent of the Roman Empire.[141] This approach to the Scientific Revolution reduces it to a period of relearning classical ideas that is very much an extension of the Renaissance. This view does not deny that a change occurred but argues that it was a reassertion of previous knowledge (a renaissance) and not the creation of new knowledge. It cites statements from Newton, Copernicus and others in favour of the Pythagorean worldview as evidence.[142][143]

In more recent analysis of the Scientific Revolution during this period, there has been criticism of not only the Eurocentric ideologies spread, but also of the dominance of male scientists of the time.[144] Science as we know it today, and the original theories that we base modern science on, was built by males, regardless of the input women might have made. The incorporation of women's work in the sciences during this time tends to be obscured. Scholars have tried to look into the participation of women in the 17th century in science, and even with sciences as simple as domestic knowledge women were making advances.[145] With the limited history provided from texts of the period we are not completely aware if women were helping these scientists develop the ideas they did. Another idea to consider is the way this period influenced even the women scientists of the periods following it. Annie Jump Cannon was an astronomer who benefitted from the laws and theories developed from this period; she made several advances in the century following the Scientific Revolution. It was an important period for the future of science, including the incorporation of women into fields using the developments made.[146]