Sleeping Princess: An early 20th-century painting by Victor Vasnetsov

The neuroscience of sleep is the study of the neuroscientific and physiological basis of the nature of sleep and its functions. Traditionally, sleep has been studied as part of psychology and medicine. The study of sleep from a neuroscience perspective grew to prominence with advances in technology and proliferation of neuroscience research from the second half of the twentieth century.

The fact that organisms daily spend hours of their time in sleep and that sleep deprivation can have disastrous effects ultimately leading to death, demonstrate the importance of sleep. For a phenomenon so important, the purposes and mechanisms of sleep are only partially understood, so much so that as recently as the late 1990s it was quipped: "The only known function of sleep is to cure sleepiness". However, the development of improved imaging techniques like EEG, PET and fMRI, along with high computational power have led to an increasingly greater understanding of the mechanisms underlying sleep.

The fundamental questions in the neuroscientific study of sleep are:

- What are the correlates of sleep i.e. what are the minimal set of events that could confirm that the organism is sleeping?

- How is sleep triggered and regulated by the brain and the nervous system?

- What happens in the brain during sleep?

- How can we understand sleep function based on physiological changes in the brain?

- What causes various sleep disorders and how can they be treated?

Introduction

Rapid eye movement sleep (REM), non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREM or non-REM), and waking represent the three major modes of consciousness, neural activity, and physiological regulation. NREM sleep itself is divided into multiple stages – N1, N2 and N3. Sleep proceeds in 90-minute cycles of REM and NREM, the order normally being N1 → N2 → N3 → N2 → REM. As humans fall asleep, body activity slows down. Body temperature, heart rate, breathing rate, and energy use all decrease. Brain waves get slower and bigger. The excitatory neurotransmitter acetylcholine becomes less available in the brain. Humans often maneuver to create a thermally friendly environment—for example, by curling up into a ball if cold. Reflexes remain fairly active.REM sleep is considered closer to wakefulness and is characterized by rapid eye movement and muscle atonia. NREM is considered to be deep sleep (the deepest part of NREM is called slow wave sleep), and is characterized by lack of prominent eye movement or muscle paralysis. Especially during non-REM sleep, the brain uses significantly less energy during sleep than it does in waking. In areas with reduced activity, the brain restores its supply of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the molecule used for short-term storage and transport of energy. (Since in quiet waking the brain is responsible for 20% of the body's energy use, this reduction has an independently noticeable impact on overall energy consumption.) During slow-wave sleep, humans secrete bursts of growth hormone. All sleep, even during the day, is associated with secretion of prolactin.

According to the Hobson & McCarley activation-synthesis hypothesis, proposed in 1975–1977, the alternation between REM and non-REM can be explained in terms of cycling, reciprocally influential neurotransmitter systems. Sleep timing is controlled by the circadian clock, and in humans, to some extent by willed behavior. The term circadian comes from the Latin circa, meaning "around" (or "approximately"), and diem or dies, meaning "day". The circadian clock refers to a biological mechanism that governs multiple biological processes causing them to display an endogenous, entrainable oscillation of about 24 hours. These rhythms have been widely observed in plants, animals, fungi and cyanobacteria.

Correlates of sleep

One of the important questions in sleep research is clearly defining the sleep state. This problem arises because sleep was traditionally defined as a state of consciousness and not as a physiological state, thus there was no clear definition of what minimum set of events constitute sleep and distinguish it from other states of partial or no consciousness. The problem of making such a definition is complicated because it needs to include a variety of modes of sleep found across different species.At a symptomatic level, sleep is characterized by lack of reactivity to sensory inputs, low motor output, diminished conscious awareness and rapid reversibility to wakefulness. However, to translate these into a biological definition is difficult because no single pathway in the brain is responsible for the generation and regulation of sleep. One of the earliest proposals was to define sleep as the deactivation of the cerebral cortex and the thalamus because of near lack of response to sensory inputs during sleep. However, this was invalidated because both regions are active in some phases of sleep. In fact, it appears that the thalamus is only deactivated in the sense of transmitting sensory information to the cortex.

Some of the other observations about sleep included decrease of sympathetic activity and increase of parasympathetic activity in non-REM sleep, and increase of heart rate and blood pressure accompanied by decrease in homeostatic response and muscle tone during REM sleep. However, these symptoms are not limited to sleep situations and do not map to specific physiological definitions.

More recently, the problem of definition has been addressed by observing overall brain activity in the form of characteristic EEG patterns. Each stage of sleep and wakefulness has a characteristic pattern of EEG which can be used to identify the stage of sleep. Waking is usually characterized by beta (12–30 Hz) and gamma (25–100 Hz) depending on whether there was a peaceful or stressful activity. The onset of sleep involves slowing down of this frequency to the drowsiness of alpha (8–12 Hz) and finally to theta (4–10 Hz) of Stage 1 NREM sleep. This frequency further decreases progressively through the higher stages of NREM and REM sleep. On the other hand, the amplitude of sleep waves is lowest during wakefulness (10–30μV) and shows a progressive increase through the various stages of sleep. Stage 2 is characterized by sleep spindles (intermittent clusters of waves at sigma frequency i.e. 12–14 Hz) and K complexes (sharp upward deflection followed by slower downward deflection). Stage 3 sleep has more sleep spindles. Stages 3 and 4 have very high amplitude delta waves (0–4 Hz) and are known as slow wave sleep. REM sleep is characterized by low amplitude, mixed frequency waves. A sawtooth wave pattern is often present.

Ontogeny and phylogeny of sleep

Animal Sleep: Image of sleeping white tiger.

The questions of how sleep evolved in the animal kingdom and how it developed in humans are especially important because they might provide a clue to the functions and mechanisms of sleep respectively.

Sleep evolution

The evolution of different types of sleep patterns is influenced by a number of selective pressures, including body size, relative metabolic rate, predation, type and location of food sources, and immune function. Sleep (especially deep SWS and REM) is tricky behavior because it steeply increases predation risk. This means that, for sleep to have evolved, the functions of sleep should have provided a substantial advantage over the risk it entails. In fact, studying sleep in different organisms shows how they have balanced this risk by evolving partial sleep mechanisms or by having protective habitats. Thus, studying the evolution of sleep might give a clue not only to the developmental aspects and mechanisms, but also to an adaptive justification for sleep.One challenge studying sleep evolution is that adequate sleep information is known only for two phyla of animals- chordata and arthropoda. With the available data, comparative studies have been used to determine how sleep might have evolved. One question that scientists try to answer through these studies is whether sleep evolved only once or multiple times. To understand this, they look at sleep patterns in different classes of animals whose evolutionary histories are fairly well-known and study their similarities and differences.

Humans possess both slow wave and REM sleep, in both phases both eyes are closed and both hemispheres of the brain involved. Sleep has also been recorded in mammals other than humans. One study showed that echidnas possess only slow wave sleep (non-REM). This seems to indicate that REM sleep appeared in evolution only after therians. But this has later been contested by studies that claim that sleep in echidna combines both modes into a single sleeping state. Other studies have shown a peculiar form of sleep in odontocetes (like dolphins and porpoises). This is called the unihemispherical slow wave sleep (USWS). At any time during this sleep mode, the EEG of one brain hemisphere indicates sleep while that of the other is equivalent to wakefulness. In some cases, the corresponding eye is open. This might allow the animal to reduce predator risk and sleep while swimming in water, though the animal may also be capable of sleeping at rest.

The correlates of sleep found for mammals are valid for birds as well i.e. bird sleep is very similar to mammals and involves both SWS and REM sleep with similar features, including closure of both eyes, lowered muscle tone, etc. However, the proportion of REM sleep in birds is much lower. Also, some birds can sleep with one eye open if there is high predation risk in the environment. This gives rise to the possibility of sleep in flight; considering that sleep is very important and some bird species can fly for weeks continuously, this seems to be the obvious result. However, sleep in flight has not been recorded, and is so far unsupported by EEG data. Further research may explain whether birds sleep during flight or if there are other mechanisms which ensure their remaining healthy during long flights in the absence of sleep.

Unlike in birds, very few consistent features of sleep have been found among reptile species. The only common observation is that reptiles do not have REM sleep.

Sleep in some invertebrates has also been extensively studied, e.g., sleep in fruitflies (Drosophila) and honeybees. Some of the mechanisms of sleep in these animals have been discovered while others remain quite obscure. The features defining sleep have been identified for the most part, and like mammals, this includes reduced reaction to sensory input, lack of motor response in the form of antennal immobility, etc.

The fact that both the forms of sleep are found in mammals and birds, but not in reptiles (which are considered to be an intermediate stage) indicates that sleep might have evolved separately in both. Substantiating this might be followed by further research on whether the EEG correlates of sleep are involved in its functions or if they are merely a feature. This might further help in understanding the role of sleep in long term plasticity.

According to Tsoukalas (2012), REM sleep is an evolutionary transformation of a well-known defensive mechanism, the tonic immobility reflex. This reflex, also known as animal hypnosis or death feigning, functions as the last line of defense against an attacking predator and consists of the total immobilization of the animal: the animal appears dead (cf. "playing possum"). The neurophysiology and phenomenology of this reaction show striking similarities to REM sleep, a fact which betrays a deep evolutionary kinship. For example, both reactions exhibit brainstem control, paralysis, sympathetic activation, and thermoregulatory changes. This theory integrates many earlier findings into a unified, and evolutionary well informed, framework.

Sleep development and aging

The ontogeny of sleep is the study of sleep across different age groups of a species, particularly during development and aging. Among mammals, infants sleep the longest. Human babies have 8 hours of REM sleep and 8 hours of NREM sleep on an average. The percentage of time spent on each mode of sleep varies greatly in the first few weeks of development and some studies have correlated this to the degree of precociality of the child. Within a few months of postnatal development, there is a marked reduction in percentage of hours spent in REM sleep. By the time the child becomes an adult, he spends about 6–7 hours in NREM sleep and only about an hour in REM sleep. This is true not only of humans, but of many animals dependent on their parents for food. The observation that the percentage of REM sleep is very high in the first stages of development has led to the hypothesis that REM sleep might facilitate early brain development. However, this theory has been contested by other studies.Sleep behavior undergoes substantial changes during adolescence. Some of these changes may be societal in humans, but other changes are hormonal. Another important change is the decrease in the number of hours of sleep, as compared to childhood, which gradually becomes identical to an adult. It is also being speculated that homeostatic regulation mechanisms may be altered during adolescence. Apart from this, the effect of changing routines of adolescents on other behavior such as cognition and attention is yet to be studied.

Sleep in aging is another equally important area of research. A common observation is that many older adults spend time awake in bed after sleep onset in an inability to fall asleep and experience marked decrease in sleep efficiency. There may also be some changes in circadian rhythms. Studies are ongoing about what causes these changes and how they may be reduced to ensure comfortable sleep of old adults.

Brain activity during sleep

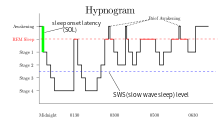

Hypnogram

showing sleep architecture from midnight to 6:30 am, with deep sleep

early on. There is more REM (marked red) before waking. (Current

hypnograms reflect the recent decision to combine NREM stages 3 and 4

into a single stage 3.)

Understanding the activity of different parts of the brain during sleep can give a clue to the functions of sleep. It has been observed that mental activity is present during all stages of sleep, though from different regions in the brain. So, contrary to popular understanding, the brain never completely shuts down during sleep. Also, sleep intensity of a particular region is homeostatically related to the corresponding amount of activity before sleeping. The use of imaging modalities like PET and fMRI, combined with EEG recordings, gives a clue to which brain regions participate in creating the characteristic wave signals and what their functions might be.

Historical development of the stages model

The stages of sleep were first described in 1937 by Alfred Lee Loomis and his coworkers, who separated the different electroencephalography (EEG) features of sleep into five levels (A to E), representing the spectrum from wakefulness to deep sleep. In 1953, REM sleep was discovered as distinct, and thus William C. Dement and Nathaniel Kleitman reclassified sleep into four NREM stages and REM. The staging criteria were standardized in 1968 by Allan Rechtschaffen and Anthony Kales in the "R&K sleep scoring manual."In the R&K standard, NREM sleep was divided into four stages, with slow-wave sleep comprising stages 3 and 4. In stage 3, delta waves made up less than 50% of the total wave patterns, while they made up more than 50% in stage 4. Furthermore, REM sleep was sometimes referred to as stage 5. In 2004, the AASM commissioned the AASM Visual Scoring Task Force to review the R&K scoring system. The review resulted in several changes, the most significant being the combination of stages 3 and 4 into Stage N3. The revised scoring was published in 2007 as The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Arousals, respiratory, cardiac, and movement events were also added.

NREM sleep activity

NREM sleep is characterized by decreased global and regional cerebral blood flow. Non-REM sleep which constitutes ~80% of all sleep in humans. Initially, it was expected that the brainstem, which was implicated in arousal would be inactive, but this was later on found to have been due to low resolution of PET studies and it was shown that there is some slow wave activity in the brainstem as well. However, other parts of the brain, including the precuneus, basal forebrain and basal ganglia are deactivated during sleep. Many areas of the cortex are also inactive, but to different levels. For example, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex is considered the least active area while the primary cortex, the least deactivated.NREM sleep is characterized by slow oscillations, spindles and delta waves. The slow oscillations have been shown to be from the cortex, as lesions in other parts of the brain do not affect them, but lesions in the cortex do. The delta waves have been shown to be generated by reciprocally connected thalamic and cortical neural circuits. During sleep, the thalamus stops relaying sensory information to the brain, however it continues to produce signals that are sent to its cortical projections. These waves are generated in the thalamus even in the absence of the cortex, but the cortical output seems to play a role in the simultaneous firing by large groups of neurons. The thalamic reticular nucleus is considered to be the pacemaker of the sleep spindles. This has been further substantiated by the fact that rhythmic stimulation of the thalamus leads to increased secondary depolarization in cortical neurons, which further results in the increased amplitude of firing, causing self-sustained activity. The sleep spindles have been predicted to play a role in disconnecting the cortex from sensory input and allowing entry of calcium ions into cells, thus potentially playing a role in Plasticity.

NREM 1

NREM Stage 1 (N1 – light sleep, somnolence, drowsy sleep – 5–10% of total sleep in adults): This is a stage of sleep that usually occurs between sleep and wakefulness, and sometimes occurs between periods of deeper sleep and periods of REM. The muscles are active, and the eyes roll slowly, opening and closing moderately. The brain transitions from alpha waves having a frequency of 8–13 Hz (common in the awake state) to theta waves having a frequency of 4–7 Hz. Sudden twitches and hypnic jerks, also known as positive myoclonus, may be associated with the onset of sleep during N1. Some people may also experience hypnagogic hallucinations during this stage. During Non-REM1, humans lose some muscle tone and most conscious awareness of the external environment.NREM 2

NREM Stage 2 (N2 – 45–55% of total sleep in adults): In this stage, theta activity is observed and sleepers become gradually harder to awaken; the alpha waves of the previous stage are interrupted by abrupt activity called sleep spindles (or thalamocortical spindles) and K-complexes. Sleep spindles range from 11 to 16 Hz (most commonly 12–14 Hz). During this stage, muscular activity as measured by EMG decreases, and conscious awareness of the external environment disappears.NREM 3

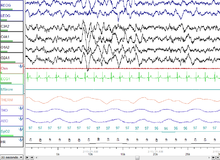

30 seconds of deep (stage N3) sleep.

NREM Stage 3 (N3 – deep sleep, slow-wave sleep – 15–25% of total sleep in adults): Formerly divided into stages 3 and 4, this stage is called slow-wave sleep (SWS) or deep sleep. SWS is initiated in the preoptic area and consists of delta activity, high amplitude waves at less than 3.5 Hz. The sleeper is less responsive to the environment; many environmental stimuli no longer produce any reactions. Slow-wave sleep is thought to be the most restful form of sleep, the phase which most relieves subjective feelings of sleepiness and restores the body.

This stage is characterized by the presence of a minimum of 20% delta waves ranging from 0.5–2 Hz and having a peak-to-peak amplitude >75 μV. (EEG standards define delta waves to be from 0 to 4 Hz, but sleep standards in both the original R&K model (Allan Rechtschaffen and Anthony Kales in the "R&K sleep scoring manual."), as well as the new 2007 AASM guidelines have a range of 0.5–2 Hz.) This is the stage in which parasomnias such as night terrors, nocturnal enuresis, sleepwalking, and somniloquy occur. Many illustrations and descriptions still show a stage N3 with 20–50% delta waves and a stage N4 with greater than 50% delta waves; these have been combined as stage N3.

REM sleep activity

A screenshot of a PSG of a person in REM sleep. Eye movements highlighted by red box

REM Stage (REM Sleep – 20–25% of total sleep in adults): REM sleep is where most muscles are paralyzed, and heart rate, breathing and body temperature become unregulated. REM sleep is turned on by acetylcholine secretion and is inhibited by neurons that secrete monoamines including serotonin. REM is also referred to as paradoxical sleep because the sleeper, although exhibiting high-frequency EEG waves similar to a waking state, is harder to arouse than at any other sleep stage. Vital signs indicate arousal and oxygen consumption by the brain is higher than when the sleeper is awake. REM sleep is characterized by high global cerebral blood flow, comparable to wakefulness. In fact, many areas in the cortex have been recorded to have more blood flow during REM sleep than even wakefulness- this includes the hippocampus, temporal-occipital areas, some parts of the cortex, and basal forebrain. The limbic and paralimbic system including the amygdala are other active regions during REM sleep. Though the brain activity during REM sleep appears very similar to wakefulness, the main difference between REM and wakefulness is that, arousal in REM is more effectively inhibited. This, along with the virtual silence of monoaminergic neurons in the brain, may be said to characterize REM.

A newborn baby spends 8 to 9 hours a day just in REM sleep. By the age of five or so, only slightly over two hours is spent in REM. The function of REM sleep is uncertain but a lack of it impairs the ability to learn complex tasks. Functional paralysis from muscular atonia in REM may be necessary to protect organisms from self-damage through physically acting out scenes from the often-vivid dreams that occur during this stage.

In EEG recordings, REM sleep is characterized by high frequency, low amplitude activity and spontaneous occurrence of beta and gamma waves. The best candidates for generation of these fast frequency waves are fast rhythmic bursting neurons in corticothalamic circuits. Unlike in slow wave sleep, the fast frequency rhythms are synchronized over restricted areas in specific local circuits between thalamocortical and neocortical areas. These are said to be generated by cholinergic processes from brainstem structures.

Apart from this, the amygdala plays a role in REM sleep modulation, supporting the hypothesis that REM sleep allows internal information processing. The high amygdalar activity may also cause the emotional responses during dreams. Similarly, the bizarreness of dreams may be due to the decreased activity of prefrontal regions, which are involved in integrating information as well as episodic memory.

Ponto-geniculo-occipital waves

REM sleep is also related to the firing of ponto-geniculo-occipital waves (also called phasic activity or PGO waves) and activity in the cholinergic ascending arousal system. The PGO waves have been recorded in the lateral geniculate nucleus and occipital cortex during the pre-REM period and are thought to represent dream content. The greater signal-to-noise ratio in the LG cortical channel suggests that visual imagery in dreams may appear before full development of REM sleep, but this has not yet been confirmed. PGO waves may also play a role in development and structural maturation of brain, as well as long term potentiation in immature animals, based on the fact that there is high PGO activity during sleep in the developmental brain.Network reactivation

The other form of activity during sleep is reactivation. Some electrophysiological studies have shown that neuronal activity patterns found during a learning task before sleep are reactivated in the brain during sleep. This, along with the coincidence of active areas with areas responsible for memory have led to the theory that sleep might have some memory consolidation functions. In this relation, some studies have shown that after a sequential motor task, the pre-motor and visual cortex areas involved are most active during REM sleep, but not during NREM. Similarly, the hippocampal areas involved in spatial learning tasks are reactivated in NREM sleep, but not in REM. Such studies suggest a role of sleep in consolidation of specific memory types. It is, however, still unclear whether other types of memory are also consolidated by these mechanisms.Hippocampal neocortical dialog

The hippocampal neocortical dialog refers to the very structured interactions during SWS between groups of neurons called ensembles in the hippocampus and neocortex. Sharp wave patterns (SPW) dominate the hippocampus during SWS and neuron populations in the hippocampus participate in organized bursts during this phase. This is done in synchrony with state changes in the cortex (DOWN/UP state) and coordinated by the slow oscillations in cortex. These observations, coupled with the knowledge that the hippocampus plays a role in short to medium term memory whereas the cortex plays a role in long term memory, have led to the hypothesis that the hippocampal neocortical dialog might be a mechanism through which the hippocampus transfers information to the cortex. Thus, the hippocampal neocortical dialog is said to play a role in memory consolidation.Sleep regulation

Sleep regulation refers to the control of when an organism transitions between sleep and wakefulness. The key questions here are to identify which parts of the brain are involved in sleep onset and what their mechanisms of action are. In humans and most animals sleep and wakefulness seems to follow an electronic flip-flop model i.e. both states are stable, but the intermediate states are not. Of course, unlike in the flip-flop, in the case of sleep, there seems to be a timer ticking away from the minute of waking so that after a certain period one must sleep, and in such a case even waking becomes an unstable state. The reverse may also be true to a lesser extent.Sleep onset

Some light was thrown on the mechanisms on sleep onset by the discovery that lesions in the preoptic area and anterior hypothalamus lead to insomnia while those in the posterior hypothalamus lead to sleepiness. Apart from this, it was found that lesions in oral pontine and midbrain reticular formation lead to loss of cortical activation. This was further narrowed down to show that the central midbrain tegmentum is the region that plays a role in cortical activation. Thus, sleep onset seems to arise from activation of the anterior hypothalamus along with inhibition of the posterior regions and the central midbrain tegmentum. Further research has shown that the hypothalamic region called ventrolateral preoptic nucleus produces the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA that inhibits the arousal system during sleep onset.Models of sleep regulation

Sleep is regulated by two parallel mechanisms, homeostatic regulation and circadian regulation, controlled by the hypothalamus and the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), respectively. Although the exact nature of sleep drive is unknown, homeostatic pressure builds up during wakefulness and this continues until the person goes to sleep. Adenosine is thought to play a critical role in this and many people have proposed that the pressure build-up is partially due to adenosine accumulation. However, some researchers have shown that accumulation alone does not explain this phenomenon completely. The circadian rhythm is a 24-hour cycle in the body, which has been shown to continue even in the absence of environmental cues. This is caused by projections from the SCN to the brain stem.This two process model was first proposed in 1982 by Borbely, who called them Process S (homeostatic) and Process C (Circadian) respectively. He showed how the slow wave density increases through the night and then drops off at the beginning of the day while the circadian rhythm is like a sinusoid. He proposed that the pressure to sleep was the maximum when the difference between the two was highest.

In 1993, a different model called the opponent process model was proposed. This model explained that these two processes opposed each other to produce sleep, as against Borbely's model. According to this model, the SCN, which is involved in the circadian rhythm, enhances wakefulness and opposes the homeostatic rhythm. In opposition is the homeostatic rhythm, regulated via a complex multisynaptic pathway in the hypothalamus that acts like a switch and shuts off the arousal system. Both effects together produce a see-saw like effect of sleep and wakefulness. More recently, it has been proposed that both models have some validity to them, while new theories hold that inhibition of NREM sleep by REM could also play a role. In any case, the two process mechanism adds flexibility to the simple circadian rhythm and could have evolved as an adaptive measure.

Thalamic regulation

Much of the brain activity in sleep has been attributed to the thalamus and it appears that the thalamus may play a critical role in SWS. The two primary oscillations in slow wave sleep, delta and the slow oscillation, can be generated by both the thalamus and the cortex. However, sleep spindles can only be generated by the thalamus, making its role very important. The thalamic pacemaker hypothesis holds that these oscillations are generated by the thalamus but the synchronization of several groups of thalamic neurons firing simultaneously depends on the thalamic interaction with the cortex. The thalamus also plays a critical role in sleep onset when it changes from tonic to phasic mode, thus acting like a mirror for both central and decentral elements and linking distant parts of the cortex to co-ordinate their activity.Ascending reticular activating system

The ascending reticular activating system consists of a set of neural subsystems that project from various thalamic nuclei and a number of dopaminergic, noradrenergic, serotonergic, histaminergic, cholinergic, and glutamatergic brain nuclei. When awake, it receives all kinds of non-specific sensory information and relays them to the cortex. It also modulates fight or flight responses and is hence linked to the motor system. During sleep onset, it acts via two pathways: a cholinergic pathway that projects to the cortex via the thalamus and a set of monoaminergic pathways that projects to the cortex via the hypothalamus. During NREM sleep this system is inhibited by GABAergic neurons in the ventrolateral preoptic area and parafacial zone, as well as other sleep-promoting neurons in distinct brain regions.Sleep function

The need and function of sleep are among the least clearly understood areas in sleep research. When asked, after 50 years of research, what he knew about the reason people sleep, William C. Dement, founder of Stanford University's Sleep Research Center, answered, "As far as I know, the only reason we need to sleep that is really, really solid is because we get sleepy." It is likely that sleep evolved to fulfill some primeval function and took on multiple functions over time (analogous to the larynx, which controls the passage of food and air, but descended over time to develop speech capabilities).The multiple hypotheses proposed to explain the function of sleep reflect the incomplete understanding of the subject. While some functions of sleep are known, others have been proposed but not completely substantiated or understood. Some of the early ideas about sleep function were based on the fact that most (if not all) external activity is stopped during sleep. Initially, it was thought that sleep was simply a mechanism for the body to "take a break" and reduce wear. Later observations of the low metabolic rates in the brain during sleep seemed to indicate some metabolic functions of sleep. This theory is not fully adequate as sleep only decreases metabolism by about 5–10%. With the development of EEG, it was found that the brain has almost continuous internal activity during sleep, leading to the idea that the function could be that of reorganization or specification of neuronal circuits or strengthening of connections. These hypotheses are still being explored. Other proposed functions of sleep include- maintaining hormonal balance, temperature regulation and maintaining heart rate.

Preservation

The "Preservation and Protection" theory holds that sleep serves an adaptive function. It protects the animal during that portion of the 24-hour day in which being awake, and hence roaming around, would place the individual at greatest risk. Organisms do not require 24 hours to feed themselves and meet other necessities. From this perspective of adaptation, organisms are safer by staying out of harm's way, where potentially they could be prey to other, stronger organisms. They sleep at times that maximize their safety, given their physical capacities and their habitats.This theory fails to explain why the brain disengages from the external environment during normal sleep. However, the brain consumes a large proportion of the body's energy at any one time and preservation of energy could only occur by limiting its sensory inputs. Another argument against the theory is that sleep is not simply a passive consequence of removing the animal from the environment, but is a "drive"; animals alter their behaviors in order to obtain sleep.

Therefore, circadian regulation is more than sufficient to explain periods of activity and quiescence that are adaptive to an organism, but the more peculiar specializations of sleep probably serve different and unknown functions. Moreover, the preservation theory needs to explain why carnivores like lions, which are on top of the food chain and thus have little to fear, sleep the most. It has been suggested that they need to minimize energy expenditure when not hunting.

Waste clearance from the brain

During sleep, metabolic waste products, such as immunoglobulins, protein fragments or intact proteins like beta-amyloid, may be cleared from the interstitium via a glymphatic system of lymph-like channels coursing along perivascular spaces and the astrocyte network of the brain. According to this model, hollow tubes between the blood vessels and astrocytes act like a spillway allowing drainage of cerebrospinal fluid carrying wastes out of the brain into systemic blood. Such mechanisms, which remain under preliminary research as of 2017, indicate potential ways in which sleep is a regulated maintenance period for brain immune functions and clearance of beta-amyloid, a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease.Restoration

Wound healing has been shown to be affected by sleep.It has been shown that sleep deprivation affects the immune system. It is now possible to state that "sleep loss impairs immune function and immune challenge alters sleep," and it has been suggested that sleep increases white blood cell counts. A 2014 study found that depriving mice of sleep increased cancer growth and dampened the immune system's ability to control cancers. Sleep has also been theorized to effectively combat the accumulation of free radicals in the brain, by increasing the efficiency of endogenous antioxidant mechanisms.

The effect of sleep duration on somatic growth is not completely known. One study recorded growth, height, and weight, as correlated to parent-reported time in bed in 305 children over a period of nine years (age 1–10). It was found that "the variation of sleep duration among children does not seem to have an effect on growth." It is well established that slow-wave sleep affects growth hormone levels in adult men. During eight hours' sleep, Van Cauter, Leproult, and Plat found that the men with a high percentage of SWS (average 24%) also had high growth hormone secretion, while subjects with a low percentage of SWS (average 9%) had low growth hormone secretion.

There is some supporting evidence of the restorative function of sleep. The sleeping brain has been shown to remove metabolic waste products at a faster rate than during an awake state. While awake, metabolism generates reactive oxygen species, which are damaging to cells. In sleep, metabolic rates decrease and reactive oxygen species generation is reduced allowing restorative processes to take over. It is theorized that sleep helps facilitate the synthesis of molecules that help repair and protect the brain from these harmful elements generated during waking. The metabolic phase during sleep is anabolic; anabolic hormones such as growth hormones (as mentioned above) are secreted preferentially during sleep.

Energy conservation could as well have been accomplished by resting quiescent without shutting off the organism from the environment, potentially a dangerous situation. A sedentary nonsleeping animal is more likely to survive predators, while still preserving energy. Sleep, therefore, seems to serve another purpose, or other purposes, than simply conserving energy. Another potential purpose for sleep could be to restore signal strength in synapses that are activated while awake to a "baseline" level, weakening unnecessary connections that to better facilitate learning and memory functions again the next day; this means the brain is forgetting some of the things we learn each day.

Endocrine function

The secretion of many hormones is affected by sleep-wake cycles. For example, melatonin, a hormonal timekeeper, is considered a strongly circadian hormone, whose secretion increases at dim light and peaks during nocturnal sleep, diminishing with bright light to the eyes. In some organisms melatonin secretion depends on sleep, but in humans it is independent of sleep and depends only on light level. Of course, in humans as well as other animals, such a hormone may facilitate coordination of sleep onset. Similarly, cortisol and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) are strongly circadian and diurnal hormones, mostly independent of sleep. In contrast, other hormones like growth hormone (GH) & prolactin are critically sleep-dependent, and are suppressed in the absence of sleep. GH has maximum increase during SWS while prolactin is secreted early after sleep onset and rises through the night. In some hormones whose secretion is controlled by light level, sleep seems to increase secretion. Almost in all cases, sleep deprivation has detrimental effects. For example, cortisol, which is essential for metabolism (it is so important that animals can die within a week of its deficiency) and affects the ability to withstand noxious stimuli, is increased by waking and during REM sleep. Similarly, TSH increases during nocturnal sleep and decreases with prolonged periods of reduced sleep, but increases during total acute sleep deprivation.Because hormones play a major role in energy balance and metabolism, and sleep plays a critical role in the timing and amplitude of their secretion, sleep has a sizable effect on metabolism. This could explain some of the early theories of sleep function that predicted that sleep has a metabolic regulation role.

Memory processing

The role of sleep in memory has long been suspected. Many initial studies focused primarily on testing the effect of sleep on memory after training a particular task (posttraining), but later studies have also confirmed the importance of pretraining sleep on learning a new task. Such behavioral and imaging measures in tests with both animal and human subjects have shown that pretraining sleep plays a critical role in preparing the memory for encoding and posttraining sleep plays a major role in memory consolidation.Further studies have looked at the specific effects of different stages of sleep on different types of memory. For example, it has been found that sleep deprivation does not significantly affect recognition of faces, but can produce a significant impairment of temporal memory (discriminating which face belonged to which set shown). Sleep deprivation was also found to increase beliefs of being correct, especially if they were wrong. Another study reported that the performance on free recall of a list of nouns is significantly worse when sleep deprived (an average of 2.8 ± 2 words) compared to having a normal night of sleep (4.7 ± 4 words). These results indicate the role of sleep on declarative memory formation. This has been further confirmed by observations of low metabolic activity in the prefrontal cortex and temporal and parietal lobes for the temporal learning and verbal learning tasks respectively. Data analysis has also shown that the neural assemblies during SWS correlated significantly more with templates than during waking hours or REM sleep. Also, post-learning, post-SWS reverberations lasted 48 hours, much longer than the duration of novel object learning (1 hour), indicating long term potentiation.

Other observations include the importance of napping: improved performance in some kinds of tasks after a 1-hour afternoon nap; studies of performance of shift workers, showing that an equal number of hours of sleep in the day is not the same as in the night. Current research studies look at the molecular and physiological basis of memory consolidation during sleep. These, along with studies of genes that may play a role in this phenomenon, together promise to give a more complete picture of the role of sleep in memory.

Renormalizing the synaptic strength

Sleep can also serve to weaken synaptic connections that were acquired over the course of the day but which are not essential to optimal functioning. In doing so, the resource demands can be lessened, since the upkeep and strengthening of synaptic connections constitutes a large portion of energy consumption by the brain and tax other cellular mechanisms such as protein synthesis for new channels. Without a mechanism like this taking place during sleep, the metabolic needs of the brain would increase over repeated exposure to daily synaptic strengthening, up to a point where the strains become excessive or untenable.Behavior change with sleep deprivation

One approach to understanding the role of sleep is to study the deprivation of it. Sleep deprivation is common and sometimes even necessary in modern societies because of occupational and domestic reasons like round-the-clock service, security or media coverage, cross-time-zone projects etc. This makes understanding the effects of sleep deprivation very important.Many studies have been done from the early 1900s to document the effect of sleep deprivation. The study of REM deprivation began with William C. Dement more than fifty years ago. He conducted a sleep and dream research project on eight subjects, all male. For a span of up to 7 days, he deprived the participants of REM sleep by waking them each time they started to enter the stage. He monitored this with small electrodes attached to their scalp and temples. As the study went on, he noticed that the more he deprived the men of REM sleep, the more often he had to wake them. Afterwards, they showed more REM sleep than usual, later named REM rebound.

The neurobehavioral basis for these has been studied only recently. Sleep deprivation has been strongly correlated with increased probability of accidents and industrial errors. Many studies have shown the slowing of metabolic activity in the brain with many hours of sleep debt. Some studies have also shown that the attention network in the brain is particularly affected by lack of sleep, and though some of the effects on attention may be masked by alternate activities (like standing or walking) or caffeine consumption, attention deficit cannot be completely avoided.

Sleep deprivation has been shown to have a detrimental effect on cognitive tasks, especially involving divergent functions or multitasking. It also has effects on mood and emotion, and there have been multiple reports of increased tendency for rage, fear or depression with sleep debt. However, some of the higher cognitive functions seem to remain unaffected albeit slower. Many of these effects vary from person to person i.e. while some individuals have high degrees of cognitive impairment with lack of sleep, in others, it has minimal effects. The exact mechanisms for the above are still unknown and the exact neural pathways and cellular mechanisms of sleep debt are still being researched.

Sleep disorders

A sleep disorder, or somnipathy, is a medical disorder of the sleep patterns of a person or animal. Polysomnography is a test commonly used for diagnosing some sleep disorders. Sleep disorders are broadly classified into dyssomnias, parasomnias, circadian rhythm sleep disorders, and other disorders including ones caused by medical or psychological conditions and sleeping sickness. Some common sleep disorders include insomnia (chronic inability to sleep), sleep apnea (abnormally low breathing during sleep), narcolepsy (excessive sleepiness at inappropriate times), cataplexy (sudden and transient loss of muscle tone), and sleeping sickness (disruption of sleep cycle due to infection). Other disorders that are being studied include sleepwalking, sleep terror and bed wetting.Studying sleep disorders is particularly useful as it gives some clues as to which parts of the brain may be involved in the modified function. This is done by comparing the imaging and histological patterns in normal and affected subjects. Treatment of sleep disorders typically involves behavioral and psychotherapeutic methods though other techniques may also be used. The choice of treatment methodology for a specific patient depends on the patient's diagnosis, medical and psychiatric history, and preferences, as well as the expertise of the treating clinician. Often, behavioral or psychotherapeutic and pharmacological approaches are compatible and can effectively be combined to maximize therapeutic benefits.

A related field is that of sleep medicine which involves the diagnosis and therapy of sleep disorders and sleep deprivation, which is a major cause of accidents. This involves a variety of diagnostic methods including polysomnography, sleep diary, multiple sleep latency test, etc. Similarly, treatment may be behavioral such as cognitive behavioral therapy or may include pharmacological medication or bright light therapy.

Dreaming

"The Knight's Dream", a 1655 painting by Antonio de Pereda

Dreams are successions of images, ideas, emotions, and sensations that occur involuntarily in the mind during certain stages of sleep (mainly the REM stage). The content and purpose of dreams are not yet clearly understood though various theories have been proposed. The scientific study of dreams is called oneirology.

There are many theories about the neurological basis of dreaming. This includes the activation synthesis theory—the theory that dreams result from brain stem activation during REM sleep; the continual activation theory—the theory that dreaming is a result of activation and synthesis but dreams and REM sleep are controlled by different structures in the brain; and dreams as excitations of long term memory—a theory which claims that long term memory excitations are prevalent during waking hours as well but are usually controlled and become apparent only during sleep.

There are multiple theories about dream function as well. Some studies claim that dreams strengthen semantic memories. This is based on the role of hippocampal neocortical dialog and general connections between sleep and memory. One study surmises that dreams erase junk data in the brain. Emotional adaptation and mood regulation are other proposed functions of dreaming.

From an evolutionary standpoint, dreams might simulate and rehearse threatening events, that were common in the organism's ancestral environment, hence increasing a persons ability to tackle everyday problems and challenges in the present. For this reason these threatening events may have been passed on in the form of genetic memories. This theory accords well with the claim that REM sleep is an evolutionary transformation of a well-known defensive mechanism, the tonic immobility reflex.

Most theories of dream function appear to be conflicting, but it is possible that many short-term dream functions could act together to achieve a bigger long-term function. It may be noted that evidence for none of these theories is entirely conclusive.

The incorporation of waking memory events into dreams is another area of active research and some researchers have tried to link it to the declarative memory consolidation functions of dreaming.

A related area of research is the neuroscience basis of nightmares. Many studies have confirmed a high prevalence of nightmares and some have correlated them with high stress levels. Multiple models of nightmare production have been proposed including neo-Freudian models as well as other models such as image contextualization model, boundary thickness model, threat simulation model etc. Neurotransmitter imbalance has been proposed as a cause of nightmares, as also affective network dysfunction- a model which claims that nightmare is a product of dysfunction of circuitry normally involved in dreaming. As with dreaming, none of the models have yielded conclusive results and studies continue about these questions.