A stock market crash is a sudden dramatic decline of stock prices across a major cross-section of a stock market, resulting in a significant loss of paper wealth. Crashes are driven by panic selling and underlying economic factors. They often follow speculation and economic bubbles.

A stock market crash is a social phenomenon where external economic events combine with crowd psychology in a positive feedback loop where selling by some market participants drives more market participants to sell. Generally speaking, crashes usually occur under the following conditions: a prolonged period of rising stock prices (a bull market) and excessive economic optimism, a market where price–earnings ratios exceed long-term averages, and extensive use of margin debt and leverage by market participants. Other aspects such as wars, large corporate hacks, changes in federal laws and regulations, and natural disasters within economically productive areas may also influence a significant decline in the stock market value of a wide range of stocks. Stock prices for corporations competing against the affected corporations may rise despite the crash.

There is no numerically specific definition of a stock market crash but the term commonly applies to declines of over 10% in a stock market index over a period of several days. Crashes are often distinguished from bear markets (periods of declining stock market prices that are measured in months or years) as crashes include panic selling and abrupt, dramatic price declines. Crashes are often associated with bear markets; however, they do not necessarily occur simultaneously. Black Monday (1987), for example, did not lead to a bear market. Likewise, the bursting of the Japanese asset price bubble occurred over several years without any notable crashes. Stock market crashes are not common.

Crashes are generally unexpected. As Niall Ferguson stated, "Before the crash, our world seems almost stationary, deceptively so, balanced, at a set point. So that when the crash finally hits — as inevitably it will — everyone seems surprised. And our brains keep telling us it’s not time for a crash."

Examples

Tulip Mania

Tulip Mania (1634–1637), in which some single tulip bulbs allegedly sold for more than 10 times the annual income of a skilled artisan, is often considered to be the first recorded economic bubble.

Panic of 1907

In 1907 and in 1908, stock prices fell by nearly 50% due to a variety of factors, led by the manipulation of copper stocks by the Knickerbocker Trust Company. Shares of United Copper rose gradually up to October, and thereafter crashed, leading to panic. Several investment trusts and banks that had invested their money in the stock market fell and started to close down. Further bank runs were prevented due to the intervention of J. P. Morgan. The panic continued to 1908 and led to the formation of the Federal Reserve in 1913.

Wall Street Crash of 1929

The economy grew for most of the Roaring Twenties. It was a technological golden age, as innovations such as the radio, automobile, aviation, telephone, and the electric power transmission grid were deployed and adopted. Companies that had pioneered these advances, including Radio Corporation of America (RCA) and General Motors, saw their stocks soar. Financial corporations also did well, as Wall Street bankers floated mutual fund companies (then known as investment trusts) like the Goldman Sachs Trading Corporation. Investors were infatuated with the returns available in the stock market, especially by the use of leverage through margin debt (i.e., borrowing money from your stockbroker to finance part of your purchase of stocks, using the bought securities as collateral).

On August 24, 1921, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) was at 63.9. By September 3, 1929, it had risen more than sixfold to 381.2. It did not regain this level for another 25 years. By the summer of 1929, it was clear that the economy was contracting, and the stock market went through a series of unsettling price declines. These declines fed investor anxiety, and events came to a head on October 24, 28, and 29 (known respectively as Black Thursday, Black Monday, and Black Tuesday).

On Black Monday, the DJIA fell 38.33 points to 260, a drop of 12.8%. The deluge of selling overwhelmed the ticker tape system that normally gave investors the current prices of their shares. Telephone lines and telegraphs were clogged and were unable to cope. This information vacuum only led to more fear and panic. The technology of the New Era, previously much celebrated by investors, now served to deepen their suffering.

The following day, Black Tuesday, was a day of chaos. Forced to liquidate their stocks because of margin calls, overextended investors flooded the exchange with sell orders. The Dow fell 30.57 points to close at 230.07 on that day. The glamour stocks of the age saw their values plummet. Across the two days, the DJIA fell 23%.

By the end of the weekend of November 11, 1929, the index stood at 228, a cumulative drop of 40% from the September high. The markets rallied in succeeding months, but it was a temporary recovery that led unsuspecting investors into further losses. The DJIA lost 89% of its value before finally bottoming out in July 1932. The crash was followed by the Great Depression, the worst economic crisis of modern times, which plagued the stock market and Wall Street throughout the 1930s.

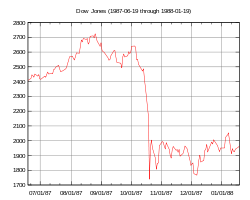

October 19, 1987

The mid-1980s were a time of strong economic optimism. From August 1982 to its peak in August 1987, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) rose from 776 to 2722. The rise in market indices for the 19 largest markets in the world averaged 296% during this period. The average number of shares traded on the New York Stock Exchange rose from 65 million shares to 181 million shares.

The crash on October 19, 1987, Black Monday, was the climactic culmination of a market decline that had begun five days before on October 14. The DJIA fell 3.81% on October 14, followed by another 4.60% drop on Friday, October 16. On Black Monday, the DJIA plummeted 508 points, losing 22.6% of its value in one day. The S&P 500 Index dropped 20.4%, falling from 282.7 to 225.06. The NASDAQ Composite lost only 11.3%, not because of restraint on the part of sellers, but because the NASDAQ market system failed. Deluged with sell orders, many stocks on the NYSE faced trading halts and delays. Of the 2,257 NYSE-listed stocks, there were 195 trading delays and halts during the day. The NASDAQ market fared much worse. Because of its reliance on a "market making" system that allowed market makers to withdraw from trading, liquidity in NASDAQ stocks dried up. Trading in many stocks encountered a pathological condition where the bid price for a stock exceeded the ask price. These "locked" conditions severely curtailed trading. On October 19, trading in Microsoft shares on the NASDAQ lasted a total of 54 minutes.

The crash was the greatest single-day loss that Wall Street had ever suffered in continuous trading up to that point. Between the start of trading on October 14 to the close on October 19, the DJIA lost 760 points, a decline of over 31%.

In October 1987, all major world markets crashed or declined substantially. The FTSE 100 Index lost 10.8% on that Monday and a further 12.2% the following day. The least affected was Austria (a fall of 11.4%) while the most affected was Hong Kong with a drop of 45.8%. Out of 23 major industrial countries, 19 had a decline greater than 20%.

Despite fears of a repeat of the Great Depression, the market rallied immediately after the crash, posting a record one-day gain of 102.27 the very next day and 186.64 points on Thursday, October 22. It took only two years for the Dow to recover completely; by September 1989, the market had regained all of the value it had lost in the 1987 crash. The DJIA gained 0.6% during calendar year 1987.

No definitive conclusions have been reached on the reasons behind the 1987 Crash. Stocks had been in a multi-year bull run and market price–earnings ratios in the U.S. were above the post-war average. The S&P 500 was trading at 23 times earnings, a postwar high and well above the average of 14.5 times earnings. Herd behavior and psychological feedback loops play a critical part in all stock market crashes but analysts have also tried to look for external triggering events. Aside from the general worries of stock market overvaluation, blame for the collapse has been apportioned to such factors as program trading, portfolio insurance and derivatives, and prior news of worsening economic indicators (i.e. a large U.S. merchandise trade deficit and a falling U.S. dollar, which seemed to imply future interest rate hikes).

One of the consequences of the 1987 Crash was the introduction of the circuit breaker or trading curb on the NYSE. Based upon the idea that a cooling-off period would help dissipate panic selling, these mandatory market shutdowns are triggered whenever a large pre-defined market decline occurs during the trading day.

Crash of 2008–2009

On September 15, 2008, the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers and the collapse of Merrill Lynch along with a liquidity crisis of American International Group, all primarily due to exposure to packaged subprime loans and credit default swaps issued to insure these loans and their issuers, rapidly devolved into a global crisis. This resulted in several bank failures in Europe and sharp reductions in the value of stocks and commodities worldwide. The failure of banks in Iceland resulted in a devaluation of the Icelandic króna and threatened the government with bankruptcy. Iceland obtained an emergency loan from the International Monetary Fund in November. In the United States, 15 banks failed in 2008, while several others were rescued through government intervention or acquisitions by other banks. On October 11, 2008, the head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) warned that the world financial system was teetering on the "brink of systemic meltdown".

The economic crisis caused countries to close their markets temporarily.

On October 8, the Indonesian stock market halted trading, after a 10% drop in one day.

The Times of London reported that the meltdown was being called the Crash of 2008, and older traders were comparing it with Black Monday in 1987. The fall that week of 21% compared to a 28.3% fall 21 years earlier, but some traders were saying it was worse. "At least then it was a short, sharp, shock on one day. This has been relentless all week." Other media also referred to the events as the "Crash of 2008".

From October 6–10, 2008, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) closed lower in all five sessions. Volume levels were record-breaking. The DJIA fell over 1,874 points, or 18%, in its worst weekly decline ever on both a points and percentage basis. The S&P 500 fell more than 20%. The week also set 3 top ten NYSE Group Volume Records with October 8 at #5, October 9 at #10, and October 10 at #1.

Having been suspended for three successive trading days (October 9, 10, and 13), the Icelandic stock market reopened on 14 October, with the main index, the OMX Iceland 15, closing at 678.4, which was about 77% lower than the 3,004.6 at the close on October 8. This reflected that the value of the three big banks, which had formed 73.2% of the value of the OMX Iceland 15, had been set to zero.

On October 24, 2008, many of the world's stock exchanges experienced the worst declines in their history, with drops of around 10% in most indices. In the U.S., the DJIA fell 3.6%, although not as much as other markets. The United States dollar and Japanese yen soared against other major currencies, particularly the British pound and Canadian dollar, as world investors sought safe havens. Later that day, the deputy governor of the Bank of England, Charlie Bean, suggested that "This is a once in a lifetime crisis, and possibly the largest financial crisis of its kind in human history."

By March 6, 2009, the DJIA had dropped 54% to 6,469 from its peak of 14,164 on October 9, 2007, over a span of 17 months, before beginning to recover.

COVID-19 pandemic (2020)

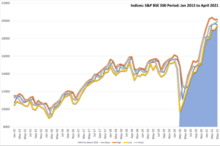

During the week of February 24–28, 2020, stock markets dropped as the COVID-19 pandemic spread globally. The FTSE 100 dropped 13%, while the DJIA and S&P 500 Index dropped 11–12% in the biggest downward weekly drop since the financial crisis of 2007–2008.

On Monday, March 9, 2020, after the launch of the 2020 Russia–Saudi Arabia oil price war, the FTSE and other major European stock market indices fell by nearly 8%. Asian markets fell sharply and the S&P 500 Index dropped 7.60%. The Italian FTSE MIB fell 2,323.98 points, or 11.17%.

On March 12, 2020, a day after US President Donald Trump announced a travel ban from Europe, stock prices again fell sharply. The DJIA declined 9.99% — the largest daily decline since Black Monday (1987) — despite the Federal Reserve announcing it would inject $1.5 trillion into money markets. The S&P 500 and the Nasdaq each dropped by approximately 9.5%. The major European stock market indexes all fell over 10%.

On March 16, 2020, after it became clear that a recession was inevitable, the DJIA dropped 12.93%, or 2,997 points, the largest point drop since Black Monday (1987), surpassing the drop in the prior week, the Nasdaq Composite dropped 12.32%, and the S&P 500 Index dropped 11.98%.

By the end of May 2020, the stock market indices briefly recovered to their levels at the end of February 2020.

In June 2020 the Nasdaq surpassed its pre-crash high followed by the S&P 500 in August and the Dow in November.

Mathematical theory

Random walk theory

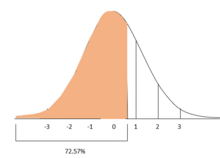

The conventional assumption is that stock markets behave according to a random log-normal distribution. This implies that the expected volatility is the same all the time. Among others, mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot suggested as early as 1963 that the statistics prove this assumption incorrect. Mandelbrot observed that large movements in prices (i.e. crashes) are much more common than would be predicted from a log-normal distribution. Mandelbrot and others suggested that the nature of market moves is generally much better explained using non-linear analysis and concepts of chaos theory. This has been expressed in non-mathematical terms by George Soros in his discussions of what he calls reflexivity of markets and their non-linear movement. George Soros said in late October 1987, 'Mr. Robert Prechter's reversal proved to be the crack that started the avalanche'.

Self-organized criticality

Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology suggests that there is evidence that the frequency of stock market crashes follows an inverse cubic power law. This and other studies such as Didier Sornette's work suggest that stock market crashes are a sign of self-organized criticality in financial markets.

Lévy flight

In 1963, Mandelbrot proposed that instead of following a strict random walk, stock price variations executed a Lévy flight. A Lévy flight is a random walk that is occasionally disrupted by large movements. In 1995, Rosario Mantegna and Gene Stanley analyzed a million records of the S&P 500 Index, calculating the returns over a five-year period. Researchers continue to study this theory, particularly using computer simulation of crowd behavior, and the applicability of models to reproduce crash-like phenomena.

Result of investor imitation

In 2011, using statistical analysis tools of complex systems, research at the New England Complex Systems Institute found that the panics that lead to crashes come from a dramatic increase in imitation among investors, which always occurred during the year before each market crash. When investors closely follow each other's cues, it is easier for panic to take hold and affect the market. This work is a mathematical demonstration of a significant advance warning sign of impending market crashes.

Trading curbs and trading halts

One mitigation strategy has been the introduction of trading curbs, also known as "circuit breakers", which are a trading halt in the cash market and the corresponding trading halt in the derivative markets triggered by the halt in the cash market, all of which are affected based on substantial movements in a broad market indicator. Since their inception after Black Monday (1987), trading curbs have been modified to prevent both speculative gains and dramatic losses within a small time frame.

United States

There are three thresholds, which represent different levels of decline in the S&P 500 Index: 7% (Level 1), 13% (Level 2), and 20% (Level 3).

- If Threshold Level 1 (a 7% drop) is breached before 3:25pm, trading halts for a minimum of 15 minutes. At or after 3:25 pm, trading continues unless there is a Level 3 halt.

- If Threshold Level 2 (a 13% drop) is breached before 1 pm, the market closes for two hours. If such a decline occurs between 1 pm and 2 pm, there is a one-hour pause. The market would close for the day if stocks sank to that level after 2 pm

- If Threshold Level 3 (a 20% drop) is breached, the market would close for the day, regardless of the time.

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {E} [X]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/44dd294aa33c0865f58e2b1bdaf44ebe911dbf93)

![{\displaystyle Z={X-\operatorname {E} [X] \over \sigma (X)}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4c8f3b9ca897926a8d0e28707f1400b9396986da)

![{\displaystyle Z={\frac {{\bar {X}}-\operatorname {E} [{\bar {X}}]}{\sigma (X)/{\sqrt {n}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2acf468c72121de0afb89521b2b709c042730963)