From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

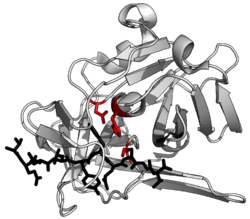

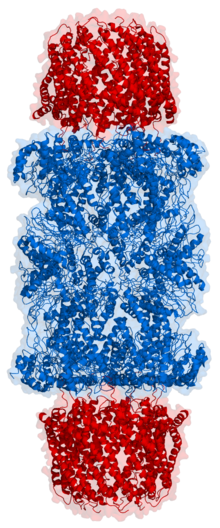

Cartoon

representation of a proteasome. Its active sites are sheltered inside

the tube (blue). The caps (red; in this case, 11S regulatory particles)

on the ends regulate entry into the destruction chamber, where the

protein is degraded.

Top view of the proteasome above.

Proteasomes are part of a major mechanism by which

cells regulate the

concentration of particular proteins and degrade

misfolded proteins. Proteins are tagged for degradation with a small protein called

ubiquitin. The tagging reaction is catalyzed by enzymes called

ubiquitin ligases.

Once a protein is tagged with a single ubiquitin molecule, this is a

signal to other ligases to attach additional ubiquitin molecules. The

result is a

polyubiquitin chain that is bound by the proteasome, allowing it to degrade the tagged protein. The degradation process yields

peptides of about seven to eight

amino acids long, which can then be further degraded into shorter amino acid sequences and used in

synthesizing new proteins.

In

structure,

the proteasome is a cylindrical complex containing a "core" of four

stacked rings forming a central pore. Each ring is composed of seven

individual proteins. The inner two rings are made of seven

β subunits that contain three to seven protease

active sites.

These sites are located on the interior surface of the rings, so that

the target protein must enter the central pore before it is degraded.

The outer two rings each contain seven

α subunits whose function

is to maintain a "gate" through which proteins enter the barrel. These α

subunits are controlled by binding to "cap" structures or

regulatory particles

that recognize polyubiquitin tags attached to protein substrates and

initiate the degradation process. The overall system of ubiquitination

and proteasomal degradation is known as the

ubiquitin-proteasome system.

Discovery

Before the discovery of the ubiquitin proteasome system, protein degradation in cells was thought to rely mainly on

lysosomes, membrane-bound

organelles with

acidic and

protease-filled interiors that can degrade and then recycle exogenous proteins and aged or damaged organelles. However, work by Joseph Etlinger and

Alfred Goldberg in 1977 on ATP-dependent protein degradation in

reticulocytes, which lack lysosomes, suggested the presence of a second intracellular degradation mechanism. This was shown in 1978 to be composed of several distinct protein chains, a novelty among proteases at the time. Later work on modification of

histones led to the identification of an unexpected

covalent modification of the histone protein by a bond between a

lysine side chain of the histone and the

C-terminal glycine residue of

ubiquitin, a protein that had no known function.

It was then discovered that a previously identified protein associated

with proteolytic degradation, known as ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1

(APF-1), was the same protein as ubiquitin.

The proteolytic activities of this system were isolated as a

multi-protein complex originally called the multi-catalytic proteinase

complex by Sherwin Wilk and Marion Orlowski. Later, the

ATP-dependent

proteolytic complex that was responsible for ubiquitin-dependent

protein degradation was discovered and was called the 26S proteasome.

Much of the early work leading up to the discovery of the

ubiquitin proteasome system occurred in the late 1970s and early 1980s

at the

Technion in the laboratory of

Avram Hershko, where

Aaron Ciechanover worked as a graduate student. Hershko's year-long sabbatical in the laboratory of

Irwin Rose at the

Fox Chase Cancer Center provided key conceptual insights, though Rose later downplayed his role in the discovery. The three shared the 2004

Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work in discovering this system.

Although

electron microscopy data revealing the stacked-ring structure of the proteasome became available in the mid-1980s, the first structure of the proteasome core particle was not solved by

X-ray crystallography until 1994.

Structure and organization

A

schematic diagram of the proteasome 20S core particle viewed from one

side. The α subunits that make up the outer two rings are shown in

green, and the β subunits that make up the inner two rings are shown in

blue.

The proteasome subcomponents are often referred to by their

Svedberg sedimentation coefficient (denoted

S). The proteasome most exclusively used in mammals is the cytosolic 26S proteasome, which is about 2000

kilodaltons (kDa) in

molecular mass

containing one 20S protein subunit and two 19S regulatory cap subunits.

The core is hollow and provides an enclosed cavity in which proteins

are degraded; openings at the two ends of the core allow the target

protein to enter. Each end of the core particle associates with a 19S

regulatory subunit that contains multiple

ATPase active sites

and ubiquitin binding sites; it is this structure that recognizes

polyubiquitinated proteins and transfers them to the catalytic core. An

alternative form of regulatory subunit called the 11S particle can

associate with the core in essentially the same manner as the 19S

particle; the 11S may play a role in degradation of foreign peptides

such as those produced after infection by a

virus.

20S core particle

The

number and diversity of subunits contained in the 20S core particle

depends on the organism; the number of distinct and specialized subunits

is larger in multicellular than unicellular organisms and larger in

eukaryotes than in prokaryotes. All 20S particles consist of four

stacked heptameric ring structures that are themselves composed of two

different types of subunits; α subunits are structural in nature,

whereas β subunits are predominantly

catalytic.

The outer two rings in the stack consist of seven α subunits each,

which serve as docking domains for the regulatory particles and the

alpha subunits N-termini form a gate that blocks unregulated access of

substrates to the interior cavity.

The inner two rings each consist of seven β subunits and contain the

protease active sites that perform the proteolysis reactions. Three

distinct catalytic activities were identified in the purified complex:

chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like and peptidylglutamyl-peptide

hydrolyzing. The size of the proteasome is relatively conserved and is about 150

angstroms

(Å) by 115 Å. The interior chamber is at most 53 Å wide, though the

entrance can be as narrow as 13 Å, suggesting that substrate proteins

must be at least partially unfolded to enter.

In

archaea such as

Thermoplasma acidophilum, all the α and all the β subunits are identical, whereas eukaryotic proteasomes such as those in

yeast contain seven distinct types of each subunit. In

mammals,

the β1, β2, and β5 subunits are catalytic; although they share a common

mechanism, they have three distinct substrate specificities considered

chymotrypsin-like,

trypsin-like, and

peptidyl-glutamyl peptide-hydrolyzing (PHGH). Alternative β forms denoted β1i, β2i, and β5i can be expressed in

hematopoietic cells in response to exposure to pro-

inflammatory signals such as

cytokines, in particular,

interferon gamma. The proteasome assembled with these alternative subunits is known as the

immunoproteasome, whose substrate specificity is altered relative to the normal proteasome.

Recently an alternative proteasome was identified in human cells that lack the α3 core subunit.

These proteasomes (known as the α4-α4 proteasomes) instead form 20S

core particles containing an additional α4 subunit in place of the

missing α3 subunit. These alternative 'α4-α4' proteasomes have been

known previously to exist in yeast.

Although the precise function of these proteasome isoforms is still

largely unknown, cells expressing these proteasomes show enhanced

resistance to toxicity induced by metallic ions such as cadmium.

19S regulatory particle

The

19S particle in eukaryotes consists of 19 individual proteins and is

divisible into two subassemblies, a 9-subunit base that binds directly

to the α ring of the 20S core particle, and a 10-subunit lid. Six of the

nine base proteins are ATPase subunits from the AAA Family, and an

evolutionary homolog of these ATPases exists in archaea, called PAN

(Proteasome-Activating Nucleotidase).

The association of the 19S and 20S particles requires the binding of

ATP to the 19S ATPase subunits, and ATP hydrolysis is required for the

assembled complex to degrade folded and ubiquitinated proteins. Note

that only the step of substrate unfolding requires energy from ATP

hydrolysis, while ATP-binding alone can support all the other steps

required for protein degradation (e.g., complex assembly, gate opening,

translocation, and proteolysis).

In fact, ATP binding to the ATPases by itself supports the rapid

degradation of unfolded proteins. However, while ATP hydrolysis is

required for unfolding only, it is not yet clear whether this energy may

be used in the coupling of some of these steps.

Cartoon representation of the 26S proteasome.

In 2012, two independent efforts have elucidated the molecular architecture of the 26S proteasome by

single particle electron microscopy. More recently, a pseudo-atomic atomic model has been built, again using cryo-EM. In the heart of the 19S, directly adjacent to the 20S, are the AAA-ATPases (

AAA proteins)

that assemble to a heterohexameric ring of the order

Rpt1/Rpt2/Rpt6/Rpt3/Rpt4/Rpt5. This ring is a trimer of dimers:

Rpt1/Rpt2, Rpt6/Rpt3, and Rpt4/Rpt5 dimerize via their N-terminal

coiled-coils. These coiled-coils protrude from the hexameric ring. The

largest regulatory particle non-ATPases Rpn1 and Rpn2 bind to the tips

of Rpt1/2 and Rpt6/3, respectively. The ubiquitin receptor Rpn13 binds

to Rpn2 and completes the base cub-complex. The lid covers one half of

the AAA-ATPase hexamer (Rpt6/Rpt3/Rpt4) and, unexpectedly, directly

contacts the 20S via Rpn6 and to lesser extent Rpn5. The subunits Rpn9,

Rpn5, Rpn6, Rpn7, Rpn3, and Rpn12, which are structurally related among

themselves and to subunits of the

COP9 complex and

eIF3

(hence called PCI subunits) assemble to a horseshoe-like structure

enclosing the Rpn8/Rpn11 heterodimer. Rpn11, the deubiquinating enzyme,

is placed at the mouth of the AAA-ATPase hexamer, ideally positioned to

remove ubiquitin moieties immediately before translocation of substrates

into the 20S. The second ubiquitin receptor identified to date, Rpn10,

is positioned at the periphery of the lid, near subunits Rpn8 and Rpn9.

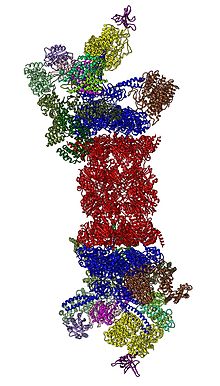

Conformational changes of 19S

The 19S regulatory particle has been observed in three strongly differing conformational states to date.

Realization of all these three conformational states is likely

necessary for accomplishing substrate recognition and degradation (see

below). A hallmark of the AAA-ATPase configuration in this predominant

low-energy state is a staircase- or lockwasher-like arrangement of the

AAA-domains. Also in the presence of

ATP

but absence of substrate an alternative, less abundant conformation of

the 19S is adopted primarily differing in the positioning of the lid

with respect to the AAA-ATPase module.

In the presence of ATP-gammaS or a substrate (stabilized in a 26S

mutant with defective Rpn11) a third conformation has been observed

displaying a dramatic structural change of the AAA-ATPase module.

Three distinct conformational states of the 26S proteasome.

The conformations are hypothesized to be responsible for recruitment of

the substrate, its irreversible commitment, and finally processing and

translocation into the core particle, where degradation occurs.

Regulation of the 20S by the 19S

The

19S regulatory particle is responsible for stimulating the 20S to

degrade proteins. A primary function of the 19S regulatory ATPases is to

open the gate in the 20S that blocks the entry of substrates into the

degradation chamber. The mechanism by which the proteasomal ATPase open this gate has been recently elucidated. 20S gate opening, and thus substrate degradation, requires the C-termini of the proteasomal ATPases, which contains a specific

motif

(i.e., HbYX motif). The ATPases C-termini bind into pockets in the top

of the 20S, and tether the ATPase complex to the 20S proteolytic

complex, thus joining the substrate unfolding equipment with the 20S

degradation machinery. Binding of these C-termini into these 20S pockets

by themselves stimulates opening of the gate in the 20S in much the

same way that a "key-in-a-lock" opens a door. The precise mechanism by which this "key-in-a-lock" mechanism functions has been structurally elucidated.

11S regulatory particle

20S

proteasomes can also associate with a second type of regulatory

particle, the 11S regulatory particle, a heptameric structure that does

not contain any ATPases and can promote the degradation of short

peptides

but not of complete proteins. It is presumed that this is because the

complex cannot unfold larger substrates. This structure is also known as

PA28 or REG. The mechanisms by which it binds to the core particle

through the C-terminal tails of its subunits and induces α-ring

conformational changes to open the 20S gate suggest a similar mechanism for the 19S particle.

The expression of the 11S particle is induced by interferon gamma and

is responsible, in conjunction with the immunoproteasome β subunits, for

the generation of peptides that bind to the

major histocompatibility complex.

Assembly

The

assembly of the proteasome is a complex process due to the number of

subunits that must associate to form an active complex. The β subunits

are synthesized with

N-terminal "propeptides" that are

post-translationally modified

during the assembly of the 20S particle to expose the proteolytic

active site. The 20S particle is assembled from two half-proteasomes,

each of which consists of a seven-membered pro-β ring attached to a

seven-membered α ring. The association of the β rings of the two

half-proteasomes triggers

threonine-dependent

autolysis of the propeptides to expose the active site. These β interactions are mediated mainly by

salt bridges and

hydrophobic interactions between conserved

alpha helices whose disruption by

mutation damages the proteasome's ability to assemble.

The assembly of the half-proteasomes, in turn, is initiated by the

assembly of the α subunits into their heptameric ring, forming a

template for the association of the corresponding pro-β ring. The

assembly of α subunits has not been characterized.

Only recently, the assembly process of the 19S regulatory

particle has been elucidated to considerable extent. The 19S regulatory

particle assembles as two distinct subcomponents, the base and the lid.

Assembly of the base complex is facilitated by four assembly

chaperones, Hsm3/S5b, Nas2/p27, Rpn14/PAAF1, and Nas6/

gankyrin (names for yeast/mammals). These assembly chaperones bind to the AAA-

ATPase subunits and their main function seems to be to ensure proper assembly of the heterohexameric AAA-

ATPase

ring. To date it is still under debate whether the base complex

assembles separately, whether the assembly is templated by the 20S core

particle, or whether alternative assembly pathways exist. In addition to

the four assembly chaperones, the deubiquitinating enzyme Ubp6/

Usp14 also promotes base assembly, but it is not essential. The lid assembles separately in a specific order and does not require assembly chaperones.

The protein degradation process

Ubiquitination and targeting

Proteins are targeted for degradation by the proteasome with covalent

modification of a lysine residue that requires the coordinated

reactions of three

enzymes. In the first step, a

ubiquitin-activating enzyme (known as E1) hydrolyzes ATP and adenylylates a

ubiquitin molecule. This is then transferred to E1's active-site

cysteine residue in concert with the adenylylation of a second ubiquitin. This adenylylated ubiquitin is then transferred to a cysteine of a second enzyme,

ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2). In the last step, a member of a highly diverse class of enzymes known as

ubiquitin ligases

(E3) recognizes the specific protein to be ubiquitinated and catalyzes

the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to this target protein. A target

protein must be labeled with at least four ubiquitin monomers (in the

form of a polyubiquitin chain) before it is recognized by the proteasome

lid. It is therefore the E3 that confers

substrate specificity to this system.

The number of E1, E2, and E3 proteins expressed depends on the organism

and cell type, but there are many different E3 enzymes present in

humans, indicating that there is a huge number of targets for the

ubiquitin proteasome system.

The mechanism by which a polyubiquitinated protein is targeted to

the proteasome is not fully understood. Ubiquitin-receptor proteins

have an

N-terminal

ubiquitin-like (UBL) domain and one or more ubiquitin-associated (UBA)

domains. The UBL domains are recognized by the 19S proteasome caps and

the UBA domains bind ubiquitin via

three-helix bundles.

These receptor proteins may escort polyubiquitinated proteins to the

proteasome, though the specifics of this interaction and its regulation

are unclear.

The

ubiquitin protein itself is 76

amino acids long and was named due to its ubiquitous nature, as it has a highly

conserved sequence and is found in all known eukaryotic organisms. The genes encoding ubiquitin in

eukaryotes are arranged in

tandem repeats, possibly due to the heavy

transcription demands on these genes to produce enough ubiquitin for the cell. It has been proposed that ubiquitin is the slowest-

evolving protein identified to date.

Ubiquitin contains seven lysine residues to which another ubiquitin can

be ligated, resulting in different types of polyubiquitin chains.

Chains in which each additional ubiquitin is linked to lysine 48 of the

previous ubiquitin have a role in proteasome targeting, while other

types of chains may be involved in other processes.

Unfolding and translocation

After a protein has been ubiquitinated, it is recognized by the 19S regulatory particle in an ATP-dependent binding step.

The substrate protein must then enter the interior of the 20S particle

to come in contact with the proteolytic active sites. Because the 20S

particle's central channel is narrow and gated by the N-terminal tails

of the α ring subunits, the substrates must be at least partially

unfolded before they enter the core. The passage of the unfolded

substrate into the core is called

translocation and necessarily occurs after deubiquitination. However, the order in which substrates are deubiquitinated and unfolded is not yet clear. Which of these processes is the

rate-limiting step

in the overall proteolysis reaction depends on the specific substrate;

for some proteins, the unfolding process is rate-limiting, while

deubiquitination is the slowest step for other proteins. The extent to which substrates must be unfolded before translocation is not known, but substantial

tertiary structure, and in particular nonlocal interactions such as

disulfide bonds, are sufficient to inhibit degradation. The presence of

intrinsically disordered protein

segments of sufficient size, either at the protein terminus or

internally, has also been proposed to facilitate efficient initiation of

degradation.

The gate formed by the α subunits prevents peptides longer than

about four residues from entering the interior of the 20S particle. The

ATP molecules bound before the initial recognition step are

hydrolyzed before translocation. While energy is needed for substrate unfolding, it is not required for translocation. The assembled 26S proteasome can degrade unfolded proteins in the presence of a non-hydrolyzable

ATP analog, but cannot degrade folded proteins, indicating that energy from ATP hydrolysis is used for substrate unfolding. Passage of the unfolded substrate through the opened gate occurs via

facilitated diffusion if the 19S cap is in the ATP-bound state.

The mechanism for unfolding of

globular proteins is necessarily general, but somewhat dependent on the

amino acid sequence. Long sequences of alternating glycine and

alanine

have been shown to inhibit substrate unfolding, decreasing the

efficiency of proteasomal degradation; this results in the release of

partially degraded byproducts, possibly due to the decoupling of the ATP

hydrolysis and unfolding steps. Such glycine-alanine repeats are also found in nature, for example in

silk fibroin; in particular, certain

Epstein–Barr virus gene products bearing this sequence can stall the proteasome, helping the virus propagate by preventing

antigen presentation on the major histocompatibility complex.

A cutaway view of the proteasome 20S core particle illustrating the locations of the active sites. The α subunits are represented as green spheres and the β subunits as protein backbones colored by individual polypeptide chain. The small pink spheres represent the location of the active-site threonine residue in each subunit. Light blue chemical structures are the inhibitor bortezomib bound to the active sites.

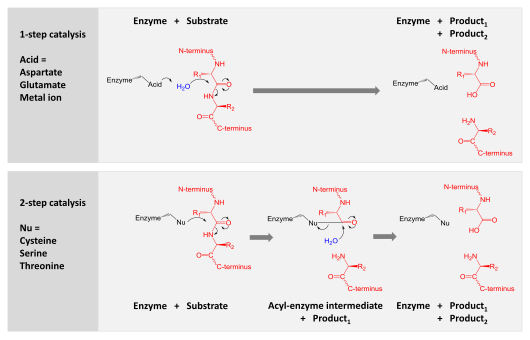

Proteolysis

The mechanism of proteolysis by the β subunits of the 20S core particle is through a threonine-dependent

nucleophilic attack. This mechanism may depend on an associated

water molecule for deprotonation of the reactive threonine

hydroxyl.

Degradation occurs within the central chamber formed by the association

of the two β rings and normally does not release partially degraded

products, instead reducing the substrate to short polypeptides typically

7–9 residues long, though they can range from 4 to 25 residues,

depending on the organism and substrate. The biochemical mechanism that

determines product length is not fully characterized.

Although the three catalytic β subunits have a common mechanism, they

have slightly different substrate specificities, which are considered

chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like, and peptidyl-glutamyl

peptide-hydrolyzing (PHGH)-like. These variations in specificity are the

result of interatomic contacts with local residues near the active

sites of each subunit. Each catalytic β subunit also possesses a

conserved lysine residue required for proteolysis.

Although the proteasome normally produces very short peptide

fragments, in some cases these products are themselves biologically

active and functional molecules. Certain

transcription factors regulating the expression of specific genes, including one component of the mammalian complex

NF-κB,

are synthesized as inactive precursors whose ubiquitination and

subsequent proteasomal degradation converts them to an active form. Such

activity requires the proteasome to cleave the substrate protein

internally, rather than processively degrading it from one terminus. It

has been suggested that long

loops

on these proteins' surfaces serve as the proteasomal substrates and

enter the central cavity, while the majority of the protein remains

outside. Similar effects have been observed in yeast proteins; this mechanism of selective degradation is known as

regulated ubiquitin/proteasome dependent processing (RUP).

Ubiquitin-independent degradation

Although

most proteasomal substrates must be ubiquitinated before being

degraded, there are some exceptions to this general rule, especially

when the proteasome plays a normal role in the post-

translational processing of the protein. The proteasomal activation of NF-κB by processing

p105 into p50 via internal proteolysis is one major example. Some proteins that are hypothesized to be unstable due to

intrinsically unstructured regions,

are degraded in a ubiquitin-independent manner. The most well-known

example of a ubiquitin-independent proteasome substrate is the enzyme

ornithine decarboxylase. Ubiquitin-independent mechanisms targeting key

cell cycle regulators such as

p53 have also been reported, although p53 is also subject to ubiquitin-dependent degradation.

Finally, structurally abnormal, misfolded, or highly oxidized proteins

are also subject to ubiquitin-independent and 19S-independent

degradation under conditions of cellular stress.

Evolution

The 20S proteasome is both ubiquitous and essential in eukaryotes. Some

prokaryotes, including many archaea and the

bacterial order

Actinomycetales, also share homologs of the 20S proteasome, whereas most bacteria possess

heat shock genes

hslV and

hslU, whose gene products are a multimeric protease arranged in a two-layered ring and an ATPase. The hslV protein has been hypothesized to resemble the likely ancestor of the 20S proteasome. In general, HslV is not essential in bacteria, and not all bacteria possess it, whereas some

protists possess both the 20S and the hslV systems.

Many bacteria also possess other homologs of the proteasome and an

associated ATPase, most notably ClpP and ClpX. This redundancy explains

why the HslUV system is not essential.

Sequence analysis suggests that the catalytic β subunits diverged

earlier in evolution than the predominantly structural α subunits. In

bacteria that express a 20S proteasome, the β subunits have high

sequence identity

to archaeal and eukaryotic β subunits, whereas the α sequence identity

is much lower. The presence of 20S proteasomes in bacteria may result

from

lateral gene transfer, while the diversification of subunits among eukaryotes is ascribed to multiple

gene duplication events.

Cell cycle control

Cell cycle progression is controlled by ordered action of

cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), activated by specific

cyclins that demarcate phases of the

cell cycle.

Mitotic cyclins, which persist in the cell for only a few minutes, have

one of the shortest life spans of all intracellular proteins.

After a CDK-cyclin complex has performed its function, the associated

cyclin is polyubiquitinated and destroyed by the proteasome, which

provides directionality for the cell cycle. In particular, exit from

mitosis requires the proteasome-dependent dissociation of the regulatory component

cyclin B from the

mitosis promoting factor complex. In

vertebrate cells, "slippage" through the mitotic checkpoint leading to premature

M phase exit can occur despite the delay of this exit by the

spindle checkpoint.

Earlier cell cycle checkpoints such as post-

restriction point check between

G1 phase and

S phase similarly involve proteasomal degradation of

cyclin A, whose ubiquitination is promoted by the

anaphase promoting complex (APC), an E3

ubiquitin ligase. The APC and the Skp1/Cul1/F-box protein complex (

SCF complex)

are the two key regulators of cyclin degradation and checkpoint

control; the SCF itself is regulated by the APC via ubiquitination of

the adaptor protein, Skp2, which prevents SCF activity before the G1-S

transition.

Individual components of the 19S particle have their own regulatory roles.

Gankyrin, a recently identified

oncoprotein, is one of the 19S subcomponents that also tightly binds the

cyclin-dependent kinase CDK4 and plays a key role in recognizing ubiquitinated

p53, via its affinity for the ubiquitin ligase

MDM2. Gankyrin is anti-

apoptotic and has been shown to be overexpressed in some

tumor cell types such as

hepatocellular carcinoma.

Regulation of plant growth

In

plants, signaling by

auxins, or

phytohormones that order the direction and

tropism of plant growth, induces the targeting of a class of

transcription factor

repressors known as Aux/IAA proteins for proteasomal degradation. These

proteins are ubiquitinated by SCFTIR1, or SCF in complex with the auxin

receptor TIR1. Degradation of Aux/IAA proteins derepresses

transcription factors in the auxin-response factor (ARF) family and

induces ARF-directed gene expression.

The cellular consequences of ARF activation depend on the plant type

and developmental stage, but are involved in directing growth in roots

and leaf veins. The specific response to ARF derepression is thought to

be mediated by specificity in the pairing of individual ARF and Aux/IAA

proteins.

Apoptosis

Both internal and external

signals can lead to the induction of

apoptosis,

or programmed cell death. The resulting deconstruction of cellular

components is primarily carried out by specialized proteases known as

caspases,

but the proteasome also plays important and diverse roles in the

apoptotic process. The involvement of the proteasome in this process is

indicated by both the increase in protein ubiquitination, and of E1, E2,

and E3 enzymes that is observed well in advance of apoptosis. During apoptosis, proteasomes localized to the nucleus have also been observed to translocate to outer membrane

blebs characteristic of apoptosis.

Proteasome inhibition has different effects on apoptosis

induction in different cell types. In general, the proteasome is not

required for apoptosis, although inhibiting it is pro-apoptotic in most

cell types that have been studied. Apoptosis is mediated through

disrupting the regulated degradation of pro-growth cell cycle proteins. However, some cell lines — in particular,

primary cultures of

quiescent and

differentiated cells such as

thymocytes and

neurons —

are prevented from undergoing apoptosis on exposure to proteasome

inhibitors. The mechanism for this effect is not clear, but is

hypothesized to be specific to cells in quiescent states, or to result

from the differential activity of the pro-apoptotic

kinase JNK.

The ability of proteasome inhibitors to induce apoptosis in rapidly

dividing cells has been exploited in several recently developed

chemotherapy agents such as

bortezomib and

salinosporamide A.

Response to cellular stress

In response to cellular stresses – such as

infection,

heat shock, or

oxidative damage –

heat shock proteins that identify misfolded or unfolded proteins and target them for proteasomal degradation are expressed. Both

Hsp27 and

Hsp90—

chaperone

proteins have been implicated in increasing the activity of the

ubiquitin-proteasome system, though they are not direct participants in

the process.

Hsp70, on the other hand, binds exposed

hydrophobic

patches on the surface of misfolded proteins and recruits E3 ubiquitin

ligases such as CHIP to tag the proteins for proteasomal degradation.

The CHIP protein (carboxyl terminus of Hsp70-interacting protein) is

itself regulated via inhibition of interactions between the E3 enzyme

CHIP and its E2 binding partner.

Similar mechanisms exist to promote the degradation of

oxidatively damaged proteins via the proteasome system. In particular, proteasomes localized to the nucleus are regulated by

PARP and actively degrade inappropriately oxidized

histones.

Oxidized proteins, which often form large amorphous aggregates in the

cell, can be degraded directly by the 20S core particle without the 19S

regulatory cap and do not require ATP hydrolysis or tagging with

ubiquitin.

However, high levels of oxidative damage increases the degree of

cross-linking between protein fragments, rendering the aggregates

resistant to proteolysis. Larger numbers and sizes of such highly

oxidized aggregates are associated with

aging.

Dysregulation of the ubiquitin proteasome system may contribute to several neural diseases. It may lead to brain tumors such as

astrocytomas. In some of the late-onset

neurodegenerative diseases that share aggregation of misfolded proteins as a common feature, such as

Parkinson's disease and

Alzheimer's disease, large insoluble aggregates of misfolded proteins can form and then result in

neurotoxicity,

through mechanisms that are not yet well understood. Decreased

proteasome activity has been suggested as a cause of aggregation and

Lewy body formation in Parkinson's. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that

yeast models of Parkinson's are more susceptible to toxicity from

α-synuclein, the major protein component of Lewy bodies, under conditions of low proteasome activity. Impaired proteasomal activity may underlie cognitive disorders such as the

autism spectrum disorders, and muscle and nerve diseases such as

inclusion body myopathy.

Role in the immune system

The proteasome plays a straightforward but critical role in the function of the

adaptive immune system. Peptide

antigens are displayed by the

major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC) proteins on the surface of

antigen-presenting cells. These peptides are products of proteasomal degradation of proteins originated by the invading

pathogen.

Although constitutively expressed proteasomes can participate in this

process, a specialized complex composed of proteins, whose

expression is induced by

interferon gamma,

are the primary producers of peptides which are optimal in size and

composition for MHC binding. These proteins whose expression increases

during the immune response include the 11S regulatory particle, whose

main known biological role is regulating the production of MHC ligands,

and specialized β subunits called β1i, β2i, and β5i with altered

substrate specificity. The complex formed with the specialized β

subunits is known as the

immunoproteasome.

Another β5i variant subunit, β5t, is expressed in the thymus, leading

to a thymus-specific "thymoproteasome" whose function is as yet unclear.

The strength of MHC class I ligand binding is dependent on the composition of the ligand

C-terminus, as peptides bind by

hydrogen bonding

and by close contacts with a region called the "B pocket" on the MHC

surface. Many MHC class I alleles prefer hydrophobic C-terminal

residues, and the immunoproteasome complex is more likely to generate

hydrophobic C-termini.

Proteasome inhibitors

Bortezomib bound to the core particle in a yeast proteasome. The bortezomib molecule is in the center colored by atom type (carbon = pink, nitrogen = blue, oxygen = red, boron = yellow), surrounded by the local protein surface. The blue patch is the catalytic threonine residue whose activity is blocked by the presence of bortezomib.

Proteasome inhibitors have effective anti-

tumor activity in

cell culture, inducing

apoptosis by disrupting the regulated degradation of pro-growth cell cycle proteins. This approach of selectively inducing apoptosis in tumor cells has proven effective in animal models and human trials.

Lactacystin, a natural product synthesized by

Streptomyces bacteria, was the first non-peptidic proteasome inhibitor discovered

and is widely used as a research tool in biochemistry and cell biology.

Lactacystin was licensed to Myogenics/Proscript, which was acquired by

Millennium Pharmaceuticals, now part of

Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

Lactacystin covalently modifies the amino-terminal threonine of

catalytic β subunits of the proteasome, particularly the β5 subunit

responsible for the proteasome's chymotrypsin-like activity. This

discovery helped to establish the proteasome as a mechanistically novel

class of protease: an amino-terminal

threonine protease.

Bortezomib (Boronated MG132), a molecule developed by

Millennium Pharmaceuticals and marketed as Velcade, is the first proteasome inhibitor to reach clinical use as a

chemotherapy agent. Bortezomib is used in the treatment of

multiple myeloma. Notably, multiple myeloma has been observed to result in increased proteasome-derived peptide levels in

blood serum that decrease to normal levels in response to successful chemotherapy. Studies in animals have indicated that bortezomib may also have clinically significant effects in

pancreatic cancer. Preclinical and early clinical studies have been started to examine bortezomib's effectiveness in treating other

B-cell-related cancers, particularly some types of

non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Clinical results also seem to justify use of proteasome inhibitor

combined with chemotherapy, for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia Proteasome inhibitors can kill some types of cultured leukemia cells that are resistant to glucocorticoids.

The molecule

ritonavir, marketed as Norvir, was developed as a

protease inhibitor and used to target

HIV infection. However, it has been shown to inhibit proteasomes as well as free proteases; to be specific, the

chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome is inhibited by ritonavir, while the

trypsin-like activity is somewhat enhanced. Studies in animal models suggest that ritonavir may have inhibitory effects on the growth of

glioma cells.

Proteasome inhibitors have also shown promise in treating

autoimmune diseases in animal models. For example, studies in mice

bearing human

skin grafts found a reduction in the size of lesions from

psoriasis after treatment with a proteasome inhibitor. Inhibitors also show positive effects in

rodent models of

asthma.

Labeling and inhibition of the proteasome is also of interest in laboratory settings for both

in vitro and

in vivo study of proteasomal activity in cells. The most commonly used laboratory inhibitors are

lactacystin and the peptide aldehyde

MG132 initially developed by Goldberg lab.

Fluorescent inhibitors have also been developed to specifically label the active sites of the assembled proteasome.

Clinical significance

The

proteasome and its subunits are of clinical significance for at least

two reasons: (1) a compromised complex assembly or a dysfunctional

proteasome can be associated with the underlying pathophysiology of

specific diseases, and (2) they can be exploited as drug targets for

therapeutic interventions. More recently, more effort has been made to

consider the proteasome for the development of novel diagnostic markers

and strategies. An improved and comprehensive understanding of the

pathophysiology of the proteasome should lead to clinical applications

in the future.

The proteasomes form a pivotal component for the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) and corresponding cellular Protein Quality Control (PQC). Protein

ubiquitination and subsequent

proteolysis and degradation by the proteasome are important mechanisms in the regulation of the

cell cycle,

cell growth and differentiation, gene transcription, signal transduction and

apoptosis.

Subsequently, a compromised proteasome complex assembly and function

lead to reduced proteolytic activities and the accumulation of damaged

or misfolded protein species. Such protein accumulation may contribute

to the pathogenesis and phenotypic characteristics in neurodegenerative

diseases, cardiovascular diseases, inflammatory responses and autoimmune diseases, and systemic DNA damage responses leading to

malignancies.

Several experimental and clinical studies have indicated that

aberrations and deregulations of the UPS contribute to the pathogenesis

of several neurodegenerative and myodegenerative disorders, including

Alzheimer's disease,

Parkinson's disease and

Pick's disease,

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (

ALS),

Huntington's disease,

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, and motor neuron diseases, polyglutamine (PolyQ) diseases,

Muscular dystrophies and several rare forms of neurodegenerative diseases associated with

dementia.

As part of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS), the proteasome

maintains cardiac protein homeostasis and thus plays a significant role

in cardiac

Ischemic injury,

ventricular hypertrophy and

Heart failure.

Additionally, evidence is accumulating that the UPS plays an essential

role in malignant transformation. UPS proteolysis plays a major role in

responses of cancer cells to stimulatory signals that are critical for

the development of cancer. Accordingly, gene expression by degradation

of

transcription factors, such as

p53,

c-Jun,

c-Fos,

NF-κB,

c-Myc, HIF-1α, MATα2,

STAT3, sterol-regulated element-binding proteins and

androgen receptors are all controlled by the UPS and thus involved in the development of various malignancies. Moreover, the UPS regulates the degradation of tumor suppressor gene products such as

adenomatous polyposis coli (

APC) in colorectal cancer,

retinoblastoma (Rb). and

von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor (VHL), as well as a number of

proto-oncogenes (

Raf,

Myc,

Myb,

Rel,

Src,

Mos,

Abl).

The UPS is also involved in the regulation of inflammatory responses.

This activity is usually attributed to the role of proteasomes in the

activation of NF-κB which further regulates the expression of pro

inflammatory

cytokines such as

TNF-α, IL-β,

IL-8,

adhesion molecules (

ICAM-1,

VCAM-1,

P-selectin) and

prostaglandins and

nitric oxide (NO).

Additionally, the UPS also plays a role in inflammatory responses as

regulators of leukocyte proliferation, mainly through proteolysis of

cyclines and the degradation of

CDK inhibitors. Lastly,

autoimmune disease patients with

SLE,

Sjogren's syndrome and

rheumatoid arthritis (RA) predominantly exhibit circulating proteasomes which can be applied as clinical biomarkers.