Hugo de Vries

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Hugo de Vries | |

|---|---|

Hugo de Vries, ca. 1907

| |

| Born | February 16, 1848 |

| Died | May 21, 1935 (aged 87)[1] |

| Institutions | Leiden University |

Definition of the gene

In 1889, De Vries published his book Intracellular Pangenesis,[4] in which, based on a modified version of Charles Darwin's theory of Pangenesis of 1868, he postulated that different characters have different hereditary carriers. He specifically postulated that inheritance of specific traits in organisms comes in particles. He called these units pangenes, a term 20 years later to be shortened to genes by Wilhelm Johannsen.Rediscovery of genetics

To support his theory of pangenes, which was not widely noticed at the time, De Vries conducted a series of experiments hybridising varieties of multiple plant species in the 1890s. Unaware of Mendel's work, De Vries used the laws of dominance and recessiveness, segregation, and independent assortment to explain the 3:1 ratio of phenotypes in the second generation.[5] His observations also confirmed his hypothesis that inheritance of specific traits in organisms comes in particles.

He further speculated that genes could cross the species barrier, with the same gene being responsible for hairiness in two different species of flower. Although generally true in a sense (orthologous genes, inherited from a common ancestor of both species, tend to stay responsible for similar phenotypes), De Vries meant a physical cross between species. This actually also happens, though very rarely in higher organisms (see horizontal gene transfer). De Vries' work on genetics inspired the research of Jantina Tammes, who worked with him for a period in 1898.

In the late 1890s, De Vries became aware of Mendel's obscure paper of thirty years earlier and he altered some of his terminology to match. When he published the results of his experiments in the French journal Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences in 1900, he neglected to mention Mendel's work, but after criticism by Carl Correns he conceded Mendel's priority.

Correns and Erich von Tschermak now share credit for the rediscovery of Mendel’s laws. Correns was a student of Nägeli, a renowned botanist with whom Mendel corresponded about his work with peas but who failed to understand its significance, while, coincidentally, Tschermak's grandfather taught Mendel botany during his student days in Vienna.

Mutation theory

In his own time, De Vries was best known for his mutation theory. In 1886 he had discovered new forms among a display of the evening primrose (Oenothera lamarckiana) growing wild in an abandoned potato field near Hilversum, having escaped a nearby garden.[6] Taking seeds from these, he found that they produced many new varieties in his experimental gardens; he introduced the term mutations for these suddenly appearing variations. In his two-volume publication The Mutation Theory (1900–1903) he postulated that evolution, especially the origin of species, might occur more frequently with such large-scale changes than via Darwinian gradualism, basically suggesting a form of saltationism. De Vries's theory was one of the chief contenders for the explanation of how evolution worked, leading, for example, Thomas Hunt Morgan to study mutations in the fruit fly, until the modern evolutionary synthesis became the dominant model in the 1930s. Somewhat ironically, the large-scale primrose variations turned out to be the result of chromosomal duplications (polyploidy), while the term mutation now generally is restricted to discrete changes in the DNA sequence.Finally, in a published lecture of 1903 (Befruchtung und Bastardierung, Veit, Leipzig), De Vries was also the first to suggest the occurrence of recombinations between homologous chromosomes, now known as chromosomal crossovers, within a year after chromosomes were implicated in Mendelian inheritance by Walter Sutton.[7]

Honors and retirement

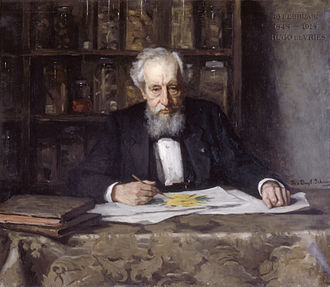

Hugo de Vries at his retirement (Thérèse Schwartze, 1918)

He retired in 1918 from the University of Amsterdam and withdrew to his estate "De Boeckhorst" in

Lunteren where he had large experimental gardens. He continued his studies with new forms until his death in 1935.