Big Bang

Condensed from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

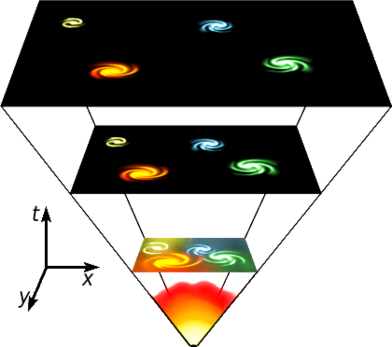

According to the Big Bang model, the universe expanded from an extremely dense and hot state and continues to expand today. The graphic scheme above is an artist's concept illustrating the expansion of a portion of a flat universe.

The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological model for the early development of the universe.[1] The key idea is that the universe is expanding. Consequently, the universe was denser and hotter in the past. Moreover, the Big Bang model suggests that at some moment all matter in the universe was contained in a single point, which is considered the beginning of the universe. Modern measurements place this moment at approximately 13.8 billion years ago, which is thus considered the age of the universe.[2] After the initial expansion, the universe cooled sufficiently to allow the formation of subatomic particles, including protons, neutrons, and electrons. Though simple atomic nuclei formed within the first three minutes after the Big Bang, thousands of years passed before the first electrically neutral atoms formed. The majority of atoms that were produced by the Big Bang are hydrogen, along with helium and traces of lithium. Giant clouds of these primordial elements later coalesced through gravity to form stars and galaxies, and the heavier elements were synthesized either within stars or during supernovae.

The Big Bang theory offers a comprehensive explanation for a broad range of observed phenomena, including the abundance of light elements, the cosmic microwave background, large scale structure, and Hubble's Law.[3] As the distance between galaxies increases today, in the past galaxies were closer together. The known laws of nature can be used to calculate the characteristics of the universe in detail back in time to extreme densities and temperatures.[4][5][6] While large particle accelerators can replicate such conditions, resulting in confirmation and refinement of the details of the Big Bang model, these accelerators can only probe so far into high energy regimes. Consequently, the state of the universe in the earliest instants of the Big Bang expansion is poorly understood and still an area of open investigation. The Big Bang theory does not provide any explanation for the initial conditions of the universe; rather, it describes and explains the general evolution of the universe going forward from that point on.

Georges Lemaître proposed what became the Big Bang theory in 1927. Over time, scientists built on his initial idea of cosmic expansion, which, his theory went, could be traced back to the origin of the cosmos and which led to formation of the modern universe. The framework for the Big Bang model relies on Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity and on simplifying assumptions such as homogeneity and isotropy of space. The governing equations were formulated by Alexander Friedmann, and similar solutions were worked on by Willem de Sitter. In 1929, Edwin Hubble discovered that the distances to far away galaxies were strongly correlated with their redshifts. Hubble's observation was taken to indicate that all distant galaxies and clusters have an apparent velocity directly away from our vantage point: that is, the farther away, the higher the apparent velocity, regardless of direction.[7] Assuming that we are not at the center of a giant explosion, the only remaining interpretation is that all observable regions of the universe are receding from each other.

While the scientific community was once divided between supporters of two different expanding universe theories—the Big Bang and the Steady State theory,[8] observational confirmation of the Big Bang scenario came with the discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation in 1964, and later when its spectrum (i.e., the amount of radiation measured at each wavelength) was found to match that of thermal radiation from a black body. Since then, astrophysicists have incorporated observational and theoretical additions into the Big Bang model, and its parametrization as the Lambda-CDM model serves as the framework for current investigations of theoretical cosmology.

Timeline of the Big Bang

Singularity

Extrapolation of the expansion of the universe backwards in time using general relativity yields an infinite density and temperature at a finite time in the past.[13] This singularity signals the breakdown of general relativity. How closely we can extrapolate towards the singularity is debated—certainly no closer than the end of the Planck epoch. This singularity is sometimes called "the Big Bang",[14] but the term can also refer to the early hot, dense phase itself,[15][notes 1] which can be considered the "birth" of our universe. Based on measurements of the expansion using Type Ia supernovae, measurements of temperature fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background, and measurements of the correlation function of galaxies, the universe has a calculated age of 13.798 ± 0.037 billion years.[17] The agreement of these three independent measurements strongly supports the ΛCDM model that describes in detail the contents of the universe.Inflation and baryogenesis

The earliest phases of the Big Bang are subject to much speculation. In the most common models the universe was filled homogeneously and isotropically with an incredibly high energy density and huge temperatures and pressures and was very rapidly expanding and cooling. Approximately 10−37 seconds into the expansion, a phase transition caused a cosmic inflation, during which the universe grew exponentially.[18] After inflation stopped, the universe consisted of a quark–gluon plasma, as well as all other elementary particles.[19] Temperatures were so high that the random motions of particles were at relativistic speeds, and particle–antiparticle pairs of all kinds were being continuously created and destroyed in collisions. At some point an unknown reaction called baryogenesis violated the conservation of baryon number, leading to a very small excess of quarks and leptons over antiquarks and antileptons—of the order of one part in 30 million. This resulted in the predominance of matter over antimatter in the present universe.[20]Cooling

Panoramic view of the entire near-infrared sky reveals the distribution of galaxies beyond the Milky Way. Galaxies are color-coded by redshift.

The universe continued to decrease in density and fall in temperature, hence the typical energy of each particle was decreasing. Symmetry breaking phase transitions put the fundamental forces of physics and the parameters of elementary particles into their present form.[21] After about 10−11 seconds, the picture becomes less speculative, since particle energies drop to values that can be attained in particle physics experiments. At about 10−6 seconds, quarks and gluons combined to form baryons such as protons and neutrons. The small excess of quarks over antiquarks led to a small excess of baryons over antibaryons. The temperature was now no longer high enough to create new proton–antiproton pairs (similarly for neutrons–antineutrons), so a mass annihilation immediately followed, leaving just one in 1010 of the original protons and neutrons, and none of their antiparticles.

A similar process happened at about 1 second for electrons and positrons. After these annihilations, the remaining protons, neutrons and electrons were no longer moving relativistically and the energy density of the universe was dominated by photons (with a minor contribution from neutrinos).

A few minutes into the expansion, when the temperature was about a billion (one thousand million; 109; SI prefix giga-) kelvin and the density was about that of air, neutrons combined with protons to form the universe's deuterium and helium nuclei in a process called Big Bang nucleosynthesis.[22] Most protons remained uncombined as hydrogen nuclei. As the universe cooled, the rest mass energy density of matter came to gravitationally dominate that of the photon radiation. After about 379,000 years the electrons and nuclei combined into atoms (mostly hydrogen); hence the radiation decoupled from matter and continued through space largely unimpeded. This relic radiation is known as the cosmic microwave background radiation.[23]

Structure formation

Over a long period of time, the slightly denser regions of the nearly uniformly distributed matter gravitationally attracted nearby matter and thus grew even denser, forming gas clouds, stars, galaxies, and the other astronomical structures observable today. The details of this process depend on the amount and type of matter in the universe. The four possible types of matter are known as cold dark matter, warm dark matter, hot dark matter, and baryonic matter. The best measurements available (from WMAP) show that the data is well-fit by a Lambda-CDM model in which dark matter is assumed to be cold (warm dark matter is ruled out by early reionization[24]), and is estimated to make up about 23% of the matter/energy of the universe, while baryonic matter makes up about 4.6%.[25] In an "extended model" which includes hot dark matter in the form of neutrinos, then if the "physical baryon density" Ωbh2 is estimated at about 0.023 (this is different from the 'baryon density' Ωb expressed as a fraction of the total matter/energy density, which as noted above is about 0.046), and the corresponding cold dark matter density Ωch2 is about 0.11, the corresponding neutrino density Ωvh2 is estimated to be less than 0.0062.[25]Cosmic acceleration

Independent lines of evidence from Type Ia supernovae and the CMB imply that the universe today is dominated by a mysterious form of energy known as dark energy, which apparently permeates all of space. The observations suggest 73% of the total energy density of today's universe is in this form.

When the universe was very young, it was likely infused with dark energy, but with less space and everything closer together, gravity predominated, and it was slowly braking the expansion. But eventually, after numerous billion years of expansion, the growing abundance of dark energy caused the expansion of the universe to slowly begin to accelerate. Dark energy in its simplest formulation takes the form of the cosmological constant term in Einstein's field equations of general relativity, but its composition and mechanism are unknown and, more generally, the details of its equation of state and relationship with the Standard Model of particle physics continue to be investigated both observationally and theoretically.[27]

All of this cosmic evolution after the inflationary epoch can be rigorously described and modeled by the ΛCDM model of cosmology, which uses the independent frameworks of quantum mechanics and Einstein's General Relativity. As noted above, there is no well-supported model describing the action prior to 10−15 seconds or so. Apparently a new unified theory of quantum gravitation is needed to break this barrier. Understanding this earliest of eras in the history of the universe is currently one of the greatest unsolved problems in physics.

Underlying assumptions

The Big Bang theory depends on two major assumptions: the universality of physical laws and the cosmological principle. The cosmological principle states that on large scales the universe is homogeneous and isotropic.These ideas were initially taken as postulates, but today there are efforts to test each of them. For example, the first assumption has been tested by observations showing that largest possible deviation of the fine structure constant over much of the age of the universe is of order 10−5.[28] Also, general relativity has passed stringent tests on the scale of the Solar System and binary stars.[notes 2]

If the large-scale universe appears isotropic as viewed from Earth, the cosmological principle can be derived from the simpler Copernican principle, which states that there is no preferred (or special) observer or vantage point. To this end, the cosmological principle has been confirmed to a level of 10−5 via observations of the CMB.[notes 3][citation needed] The universe has been measured to be homogeneous on the largest scales at the 10% level.[29]

Expansion of space

General relativity describes spacetime by a metric, which determines the distances that separate nearby points. The points, which can be galaxies, stars, or other objects, themselves are specified using a coordinate chart or "grid" that is laid down over all spacetime. The cosmological principle implies that the metric should be homogeneous and isotropic on large scales, which uniquely singles out the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric (FLRW metric). This metric contains a scale factor, which describes how the size of the universe changes with time. This enables a convenient choice of a coordinate system to be made, called comoving coordinates. In this coordinate system the grid expands along with the universe, and objects that are moving only due to the expansion of the universe remain at fixed points on the grid. While their coordinate distance (comoving distance) remains constant, the physical distance between two such comoving points expands proportionally with the scale factor of the universe.[30]The Big Bang is not an explosion of matter moving outward to fill an empty universe. Instead, space itself expands with time everywhere and increases the physical distance between two comoving points. Because the FLRW metric assumes a uniform distribution of mass and energy, it applies to our universe only on large scales—local concentrations of matter such as our galaxy are gravitationally bound and as such do not experience the large-scale expansion of space.

Horizons

An important feature of the Big Bang spacetime is the presence of horizons. Since the universe has a finite age, and light travels at a finite speed, there may be events in the past whose light has not had time to reach us. This places a limit or a past horizon on the most distant objects that can be observed. Conversely, because space is expanding, and more distant objects are receding ever more quickly, light emitted by us today may never "catch up" to very distant objects. This defines a future horizon, which limits the events in the future that we will be able to influence. The presence of either type of horizon depends on the details of the FLRW model that describes our universe. Our understanding of the universe back to very early times suggests that there is a past horizon, though in practice our view is also limited by the opacity of the universe at early times. So our view cannot extend further backward in time, though the horizon recedes in space. If the expansion of the universe continues to accelerate, there is a future horizon as well.[31]Observational evidence

Artist's depiction of the WMAP satellite gathering data to help scientists understand the Big Bang

The earliest and most direct observational evidence of the validity of the theory are the expansion of the universe according to Hubble's law (as indicated by the redshifts of galaxies), discovery and measurement of the cosmic microwave background and the relative abundances of light elements produced by Big Bang nucleosynthesis. More recent evidence includes observations of galaxy formation and evolution, and the distribution of large-scale cosmic structures,[58] These are sometimes called the "four pillars" of the Big Bang theory.[59]

Precise modern models of the Big Bang appeal to various exotic physical phenomena that have not been observed in terrestrial laboratory experiments or incorporated into the Standard Model of particle physics. Of these features, dark matter is currently subjected to the most active laboratory investigations.[60] Remaining issues include the cuspy halo problem and the dwarf galaxy problem of cold dark matter. Dark energy is also an area of intense interest for scientists, but it is not clear whether direct detection of dark energy will be possible.[61] Inflation and baryogenesis remain more speculative features of current Big Bang models.[notes 5][citation needed] Viable, quantitative explanations for such phenomena are still being sought. These are currently unsolved problems in physics.

Hubble's law and the expansion of space

Observations of distant galaxies and quasars show that these objects are redshifted—the light emitted from them has been shifted to longer wavelengths. This can be seen by taking a frequency spectrum of an object and matching the spectroscopic pattern of emission lines or absorption lines corresponding to atoms of the chemical elements interacting with the light. These redshifts are uniformly isotropic, distributed evenly among the observed objects in all directions. If the redshift is interpreted as a Doppler shift, the recessional velocity of the object can be calculated. For some galaxies, it is possible to estimate distances via the cosmic distance ladder. When the recessional velocities are plotted against these distances, a linear relationship known as Hubble's law is observed:[7]- v = H0D,

- v is the recessional velocity of the galaxy or other distant object,

- D is the comoving distance to the object, and

- H0 is Hubble's constant, measured to be 70.4 +1.3

−1.4 km/s/Mpc by the WMAP probe.[25]

The theory requires the relation v = HD to hold at all times, where D is the comoving distance, v is the recessional velocity, and v, H, and D vary as the universe expands (hence we write H0 to denote the present-day Hubble "constant"). For distances much smaller than the size of the observable universe, the Hubble redshift can be thought of as the Doppler shift corresponding to the recession velocity v. However, the redshift is not a true Doppler shift, but rather the result of the expansion of the universe between the time the light was emitted and the time that it was detected.[62]

That space is undergoing metric expansion is shown by direct observational evidence of the Cosmological principle and the Copernican principle, which together with Hubble's law have no other explanation. Astronomical redshifts are extremely isotropic and homogeneous,[7] supporting the Cosmological principle that the universe looks the same in all directions, along with much other evidence. If the redshifts were the result of an explosion from a center distant from us, they would not be so similar in different directions.

Measurements of the effects of the cosmic microwave background radiation on the dynamics of distant astrophysical systems in 2000 proved the Copernican principle, that, on a cosmological scale, the Earth is not in a central position.[63] Radiation from the Big Bang was demonstrably warmer at earlier times throughout the universe. Uniform cooling of the cosmic microwave background over billions of years is explainable only if the universe is experiencing a metric expansion, and excludes the possibility that we are near the unique center of an explosion.

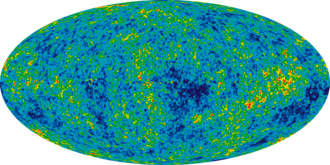

Cosmic microwave background radiation

In 1964 Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson serendipitously discovered the cosmic background radiation, an omnidirectional signal in the microwave band.[54] Their discovery provided substantial confirmation of the general CMB predictions: the radiation was found to be consistent with an almost perfect black body spectrum in all directions; this spectrum has been redshifted by the expansion of the universe, and today corresponds to approximately 2.725 K. This tipped the balance of evidence in favor of the Big Bang model, and Penzias and Wilson were awarded a Nobel Prize in 1978.

The cosmic microwave background spectrum measured by the FIRAS instrument on the COBE satellite is the most-precisely measured black body spectrum in nature.[67] The data points and error bars on this graph are obscured by the theoretical curve.

The surface of last scattering corresponding to emission of the CMB occurs shortly after recombination, the epoch when neutral hydrogen becomes stable. Prior to this, the universe comprised a hot dense photon-baryon plasma sea where photons were quickly scattered from free charged particles. Peaking at around 372±14 kyr,[24] the mean free path for a photon becomes long enough to reach the present day and the universe becomes transparent.

In 1989 NASA launched the Cosmic Background Explorer satellite (COBE). Its findings were consistent with predictions regarding the CMB, finding a residual temperature of 2.726 K (more recent measurements have revised this figure down slightly to 2.725 K) and providing the first evidence for fluctuations (anisotropies) in the CMB, at a level of about one part in 105.[55] John C. Mather and George Smoot were awarded the Nobel Prize for their leadership in this work. During the following decade, CMB anisotropies were further investigated by a large number of ground-based and balloon experiments. In 2000–2001 several experiments, most notably BOOMERanG, found the shape of the universe to be spatially almost flat by measuring the typical angular size (the size on the sky) of the anisotropies.

In early 2003 the first results of the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) were released, yielding what were at the time the most accurate values for some of the cosmological parameters. The results disproved several specific cosmic inflation models, but are consistent with the inflation theory in general.[56] The Planck space probe was launched in May 2009. Other ground and balloon based cosmic microwave background experiments are ongoing.

Abundance of primordial elements

Using the Big Bang model it is possible to calculate the concentration of helium-4, helium-3, deuterium, and lithium-7 in the universe as ratios to the amount of ordinary hydrogen.[22] The relative abundances depend on a single parameter, the ratio of photons to baryons. This value can be calculated independently from the detailed structure of CMB fluctuations. The ratios predicted (by mass, not by number) are about 0.25 for 4He/H, about 10−3 for 2H/H, about 10−4 for 3He/H and about 10−9 for 7Li/H.[22]The measured abundances all agree at least roughly with those predicted from a single value of the baryon-to-photon ratio. The agreement is excellent for deuterium, close but formally discrepant for 4He, and off by a factor of two 7Li; in the latter two cases there are substantial systematic uncertainties. Nonetheless, the general consistency with abundances predicted by Big Bang nucleosynthesis is strong evidence for the Big Bang, as the theory is the only known explanation for the relative abundances of light elements, and it is virtually impossible to "tune" the Big Bang to produce much more or less than 20–30% helium.[68] Indeed there is no obvious reason outside of the Big Bang that, for example, the young universe (i.e., before star formation, as determined by studying matter supposedly free of stellar nucleosynthesis products) should have more helium than deuterium or more deuterium than 3He, and in constant ratios, too.

Galactic evolution and distribution

Detailed observations of the morphology and distribution of galaxies and quasars are in agreement with the current state of the Big Bang theory. A combination of observations and theory suggest that the first quasars and galaxies formed about a billion years after the Big Bang, and since then larger structures have been forming, such as galaxy clusters and superclusters. Populations of stars have been aging and evolving, so that distant galaxies (which are observed as they were in the early universe) appear very different from nearby galaxies (observed in a more recent state). Moreover, galaxies that formed relatively recently appear markedly different from galaxies formed at similar distances but shortly after the Big Bang. These observations are strong arguments against the steady-state model. Observations of star formation, galaxy and quasar distributions and larger structures agree well with Big Bang simulations of the formation of structure in the universe and are helping to complete details of the theory.[69][70]Primordial gas clouds

Focal plane of BICEP2 telescope under a microscope - may have detected gravitational waves from the infant universe.[9][10][11][12]

In 2011 astronomers found what they believe to be pristine clouds of primordial gas, by analyzing absorption lines in the spectra of distant quasars. Before this discovery, all other astronomical objects have been observed to contain heavy elements that are formed in stars. These two clouds of gas contain no elements heavier than hydrogen and deuterium.[71][72] Since the clouds of gas have no heavy elements, they likely formed in the first few minutes after the Big Bang, during Big Bang nucleosynthesis. Their composition matches the composition predicted from Big Bang nucleosynthesis. This provides direct evidence that there was a period in the history of the universe before the formation of the first stars, when most ordinary matter existed in the form of clouds of neutral hydrogen.

Other lines of evidence

The age of universe as estimated from the Hubble expansion and the CMB is now in good agreement with other estimates using the ages of the oldest stars, both as measured by applying the theory of stellar evolution to globular clusters and through radiometric dating of individual Population II stars.[73]The prediction that the CMB temperature was higher in the past has been experimentally supported by observations of very low temperature absorption lines in gas clouds at high redshift.[74] This prediction also implies that the amplitude of the Sunyaev–Zel'dovich effect in clusters of galaxies does not depend directly on redshift. Observations have found this to be roughly true, but this effect depends on cluster properties that do change with cosmic time, making precise measurements difficult.[75][76]

On 17 March 2014, astronomers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics announced the apparent detection of primordial gravitational waves, which, if confirmed, may provide strong evidence for inflation and the Big Bang.[9][10][11][12] However, on 19 June 2014, lowered confidence in confirming the findings was reported.[77][78][79]