From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

To Arabic-speaking people, sharia (/ʃɑːˈriːɑː/;[1] also shari'a, sharīʿah; Arabic: شريعة šarīʿah, IPA: [ʃaˈriːʕa], "legislation") means the moral code and religious law of a prophetic religion.[2][3][4] The term "sharia" has been largely identified with Islam in English usage.[5]

Sharia (Islamic law) deals with several topics including: crime, politics, and economics, as well as personal matters such as sexual intercourse, hygiene, diet, prayer, everyday etiquette and fasting.

Adherence to Islamic law has served as one of the distinguishing characteristics of the Muslim faith historically, and through the centuries Muslims have devoted much scholarly time and effort on its elaboration.[6] Interpretations of sharia (fiqh) vary between Islamic sects and respective schools of jurisprudence, yet in its strictest and most historically coherent definition, sharia is considered the infallible law of God.[7]

Sharia Law is a significant source of legislation in various Muslim countries, namely Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Iran, Brunei, United Arab Emirates and Qatar. In those countries, harsh physical punishments such as flogging and stoning are said to be legally-acceptable according to Sharia. There are two primary sources of sharia law: the precepts set forth in the Quranic verses (ayat), and the example set by the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the Sunnah.[8] Where it has official status, sharia is interpreted by Islamic judges (qadis) with varying responsibilities for the religious leaders (imams). For questions not directly addressed in the primary sources, the application of sharia is extended through consensus of the religious scholars (ulama) thought to embody the consensus of the Muslim Community (ijma). Islamic jurisprudence will also sometimes incorporate analogies from the Quran and Sunnah through qiyas, though many scholars also prefer reasoning ('aql) to analogy.[7][8]

The introduction of Sharia is a longstanding goal for Islamist movements globally, including in Western countries, but attempts to impose sharia have been accompanied by controversy,[9] violence,[10] and even warfare.[11] Most countries do not recognize sharia; however, some countries in Asia, Africa and Europe recognize sharia and use it as the basis for divorce, inheritance and other personal affairs of their Islamic population.[12] In Britain, the Muslim Arbitration Tribunal makes use of sharia family law to settle disputes, and this limited adoption of sharia is controversial.[13]

The concept of crime, judicial process, justice and punishment embodied in sharia is different from that of secular law.[14] The differences between sharia and secular laws have led to an ongoing controversy as to whether sharia is compatible with secular forms of government, the human right "freedom of thought," and in general "women's rights."[15][16][17]

Etymology and origins

Scholars describe the word sharia as an archaic Arabic word denoting "pathway to be followed"(analogous to the Hebrew term Halakhah ["The Way to Go"]),[19][20] or "path to the water hole".[23] The latter definition comes from the fact that the path to water is the whole way of life in an arid desert environment.[21]The etymology of sharia as a "path" or "way" comes from the Quranic verse[Quran 45:18]: "Then we put thee on the (right) Way of religion so follow thou that (Way), and follow not the desires of those who know not."[20] Malik Ghulam Farid in his Dictionary of the Holy Quran, believes the "Way" in 45:18 (quoted above) derives from shara'a (as prf. 3rd. p.m. sing.), meaning "He ordained". Other forms also appear: shara'u[Quran 45:13] as (prf. 3rd. p.m. plu.), "they decreed (a law)"[Quran 42:21]; and shir'atun (n.) meaning "spiritual law"[Quran 5:48].[24]

The Arabic word sharīʿa has origins in the concept of ‘religious law’; the word is commonly used by Arabic-speaking peoples of the Middle East and designates a prophetic religion in its totality. Thus, sharīʿat Mūsā means religious law of Moses (Judaism), sharīʿat al-Masīḥ means religious law of Christianity, sharīʿat al-Madjūs means religious law of Zoroastrianism.[3] The Arabic expression شريعة الله (God’s Law) is a common translation for תורת אלוהים (‘God’s Law’ in Hebrew) and νόμος τοῦ θεοῦ (‘God’s Law’ in Greek in the New Testament [Rom. 7: 22]).[25] In contemporary Islamic literature, sharia refers to divine law of Islam as revealed by prophet Muhammad, as well as in his function as model and exemplar of the law.[3]

Sharia in the Islamic world is also known as Qānūn-e Islāmī (قانون اسلامی).[citation needed]

History

In Islam, the origin of sharia is the Qu'ran, and traditions gathered from the life of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad (born ca. 570 CE in Mecca).[26]Sharia underwent fundamental development, beginning with the reigns of caliphs Abu Bakr (632–34) and Umar (634–44) for Sunni Muslims, and Imam Ali for Shia Muslims, during which time many questions were brought to the attention of Muhammad's closest comrades for consultation.[27] During the reign of Muawiya b. Abu Sufyan ibn Harb, ca. 662 CE, Islam undertook an urban transformation, raising questions not originally covered by Islamic law.[27] Since then, changes in Islamic society have played an ongoing role in developing sharia, which branches out into fiqh and Qanun respectively.

The formative period of fiqh stretches back to the time of the early Muslim communities. In this period, jurists were more concerned with pragmatic issues of authority and teaching than with theory.[28] Progress in theory was started by 8th and 9th century Islamic scholars Abu Hanifa, Malik bin Anas, Al-Shafi'i, Ahmad ibn Hanbal and others.[29][30] Al-Shafi‘i is credited with deriving the theory of valid norms for sharia (uṣūl al-fiqh), arguing for a traditionalist, literal interpretation of Quran, Hadiths and methodology for law as revealed therein, to formulate sharia.[31][32]

A number of legal concepts and institutions were developed by Islamic jurists during the classical period of Islam, known as the Islamic Golden Age, dated from the 7th to 13th centuries. These shaped different versions of Sharia in different schools of Islamic jurisprudence, called fiqhs.[33][34][35]

The Umayyads initiated the office of appointing qadis, or Islamic judges. The jurisdiction of the qadi extended only to Muslims, while non-Muslim populations retained their own legal institutions.[36] The qadis were usually pious specialists in Islam. As these grew in number, they began to theorize and systemize Islamic jurisprudence.[37] The Abbasid made the institution of qadi independent from the government, but this separation wasn't always respected.[38]

Both the Umayyad caliph Umar II and the Abbasids had agreed that the caliph could not legislate contrary to the Quran or the sunnah. Imam Shafi'i declared: "a tradition from the Prophet must be accepted as soon as it become known...If there has been an action on the part of a caliph, and a tradition from the Prophet to the contrary becomes known later, that action must be discarded in favor of the tradition from the Prophet." Thus, under the Abbasids the main features of sharia were definitively established and sharia was recognized as the law of behavior for Muslims.[39]

In modern times, the Muslim community have divided points of view: secularists believe that the law of the state should be based on secular principles, not on Islamic legal doctrines; traditionalists believe that the law of the state should be based on the traditional legal schools;[40] reformers believe that new Islamic legal theories can produce modernized Islamic law[41] and lead to acceptable opinions in areas such as women's rights.[42] This division persists until the present day (Brown 1996, Hallaq 2001, Ramadan 2005, Aslan 2006, Safi 2003, Nenezich 2006).

There has been a growing religious revival in Islam, beginning in the eighteenth century and continuing today. This movement has expressed itself in various forms ranging from wars to efforts towards improving education.[43][44]

Definitions and descriptions

Sharia, in its strictest definition, is a divine law, as expressed in the Quran and Muhammad's example (often called the sunnah). As such, it is related to but different from fiqh, which is emphasized as the human interpretation of the law.[45][46] Many scholars have pointed out that the sharia is not formally a code,[47] nor a well-defined set of rules.[48] The sharia is characterized as a discussion on the duties of Muslims[47] based on both the opinion of the Muslim community and extensive literature.[49] Hunt Janin and Andre Kahlmeyer thus conclude that the sharia is "long, diverse, and complicated."[48]From the 9th century onward, the power to interpret and refine law in traditional Islamic societies was in the hands of the scholars (ulema). This separation of powers served to limit the range of actions available to the ruler, who could not easily decree or reinterpret law independently and expect the continued support of the community.[50] Through succeeding centuries and empires, the balance between the ulema and the rulers shifted and reformed, but the balance of power was never decisively changed.[51] At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution and the French Revolution introduced an era of European world hegemony that included the domination of most of the lands of Islam.[52][53] At the end of the Second World War, the European powers found themselves too weakened to maintain their empires.[54] The wide variety of forms of government, systems of law, attitudes toward modernity and interpretations of sharia are a result of the ensuing drives for independence and modernity in the Muslim world.[55][56]

According to Jan Michiel Otto, Professor of Law and Governance in Developing Countries at Leiden University, "Anthropological research shows that people in local communities often do not distinguish clearly whether and to what extent their norms and practices are based on local tradition, tribal custom, or religion. Those who adhere to a confrontational view of sharia tend to ascribe many undesirable practices to sharia and religion overlooking custom and culture, even if high-ranking religious authorities have stated the opposite." Otto's analysis appears in a paper commissioned by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[57]

Sources of sharia law

There are two sources of Sharia (understood as the divine law): the Quran and Sunnah. The Quran is viewed as the unalterable word of God. It is considered in Islam an infallible part of Sharia. Quran covers a host of topics including God, personal laws for Muslim men and Muslim women, laws on community life, laws on expected interaction of Muslims with non-Muslims, apostates and ex-Muslims, laws on finance, morals, eschatology, and others.[58][59] The Sunnah is the life and example of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. The Sunnah's importance as a source of Sharia, is confirmed by several verses of the Quran (e.g. [Quran 33:21]).[60] The Sunnah is primarily contained in the hadith or reports of Muhammad's sayings, his actions, his tacit approval of actions and his demeanor. While there is only one Quran, there are many compilations of hadith, with the most authentic ones forming during the sahih period (850 to 915 CE). The six acclaimed Sunni collections were compiled by (in order of decreasing importance) Muhammad al-Bukhari, Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj, Abu Dawood, Tirmidhi, Al-Nasa'i, Ibn Majah. The collections by al-Bukhari and Muslim, regarded the most authentic, contain about 7,000 and 12,000 hadiths respectively (although the majority of entries are repetitions). The hadiths have been evaluated on authenticity, usually by determining the reliability of the narrators that transmitted them.[61] For Shias, the Sunnah may also include anecdotes The Twelve Imams.[62]Quran versus Hadiths

Quranists, a small but vocal modernist group of Muslims reject the Hadiths as a source of law.[63][64] They suggest that the verses in the Quran should be the only source for formulating Islamic Law, and only laws derived exclusively from the Quran are valid.[65] They state that the hadiths in modern use are not explicitly mentioned in the Quran as a source of Islamic theology and practice, was not recorded in written form until more than two centuries after the death of the prophet Muhammed, and contain perceived internal errors & contradictions and also may not be relevant in current times.[63]The vast majority of Muslims, however, consider hadiths, which describe the words, conduct and example set by Muhammad during his life, as a source of law and religious authority second only to the Qur'an.[63] Similarly, most Islamic scholars believe both Quran and sahih hadiths to be a valid source of Sharia, with Quranic verse 33.21, among others,[66][67] as justification for this belief.[64]

Ye have indeed in the Messenger of Allah a beautiful pattern (of conduct) for any one whose hope is in Allah and the Final Day, and who engages much in the Praise of Allah.For vast majority of Muslims, Sharia has historically been, and continues to be derived from both Quran and Sahih Hadiths. The Sahih Hadiths contain isnad, or a chain of guarantors reaching back to a companion of Muhammad who directly observed the words, conduct and example he set – thus providing the theological ground to consider the hadith to be a sound basis for sharia.[64][67] For Sunni Muslims, the musannaf in Sahih Bukhari and Sahih Muslim is most trusted and relied upon as source for Sunni Sharia.[68] Shia Muslims, however, do not consider the chain of transmitters of Sunni hadiths as reliable, given these transmitters belonged to Sunni side in Sunni-Shia civil wars that followed after Muhammad's death.[69] Shia rely on their own chain of reliable guarantors, trusting compilations such as Kitab al-Kafi and Tahdhib al-Ahkam instead, and later hadiths (usually called akhbār by Shi'i).[70][71] The Shia version of hadiths contain the words, conduct and example set by Muhammad and Imams, which they consider as sinless, infallible and an essential source for Sharia for Shi'ite Muslims.[69][72] However, in substance, the Shi'ite hadiths resemble the Sunni hadiths, with one difference – the Shia hadiths additionally include words and actions of its Imams (al-hadith al-walawi), the biological descendants of Muhammad, and these too are considered an important source for Sharia by Shi'ites.[70][73]

It is not fitting for a Believer, man or woman, when a matter has been decided by Allah and His Messenger to have any option about their decision: if any one disobeys Allah and His Messenger, he is indeed on a clearly wrong Path.

Islamic jurisprudence (Fiqh)

Fiqh (school of Islamic jurisprudence) represents the process of deducing and applying Sharia principles, as well as the collective body of specific laws deduced from Sharia using the fiqh methodology.[29] While Quran and Hadith sources are regarded as infallible, the fiqh standards may change in different contexts. Fiqh covers all aspects of law, including religious, civil, political, constitutional and procedural law.[74] Fiqh deploys the following to create Islamic laws:[29]- Injunctions, revealed principles and interpretations of the Quran (Used by all schools and sects of Islam)

- Interpretation of the Sunnah (Muhammad's practices, opinions and traditions) and principles therein, after establishing the degree of reliability of hadith's chain of reporters (Used by all schools and sects of Islam)

- Ijma, collective reasoning and consensus amongst authoritative Muslims of a particular generation, and its interpretation by Islamic scholars. This fiqh principle for sharia is derived from Quranic verse 4:59.[75] Typically, the recorded consensus of Sahabah (Muhammad's companions) is considered authoritative and most trusted. If this is unavailable, then the recorded individual reasoning (Ijtihad) of Muhammad companions is sought. In Islam's history, some Muslim scholars have argued that Ijtihad allows individual reasoning of both the earliest generations of Muslims and later generation Muslims, while others have argued that Ijtihad allows individual reasoning of only the earliest generations of Muslims. (Used by all schools of Islam, Jafari fiqh accepts only Ijtihad of Shia Imams)[29][76]

- Qiyas, analogy is deployed if Ijma or historic collective reasoning on the issue is not available. Qiyas represents analogical deduction, the support for using it in fiqh is based on Quranic verse 2:59, and this methodology was started by Abu Hanifa.[77] This principle is considered weak by Hanbali fiqh, and it usually avoids Qiyas for sharia. (Used by all Sunni schools of Islam, but rejected by Shia Jafari)[29][78]

- Istihsan, which is the principle of serving the interest of Islam and public as determined by Islamic jurists. This method is deployed if Ijtihad and Qiyas fail to provide guidance. It was started by Hanafi fiqh as a form of Ijtihad (individual reasoning). Maliki fiqh called it Masalih Al-Mursalah, or departure from strict adherence to the Texts for public welfare. The Hanbali fiqh called it Istislah and rejected it, as did Shafi'i fiqh. (Used by Hanafi, Maliki, but rejected by Shafii, Hanbali and Shia Jafari fiqhs)[29][31][78]

- Istihab and Urf which mean continuity of pre-Islamic customs and customary law. This is considered as the weakest principle, accepted by just two fiqhs, and even in them recognized only when the custom does not violate or contradict any Quran, Hadiths or other fiqh source. (Used by Hanafi, Maliki, but rejected by Shafii, Hanbali and Shia Jafari fiqhs)[29][78]

- Schools of law

A Madhhab is a Muslim school of law that follows a fiqh (school of religious jurisprudence). In the first 150 years of Islam, there were many madhhab. Several of the Sahābah, or contemporary "companions" of Muhammad, are credited with founding their own. In the Sunni sect of Islam, the Islamic jurisprudence schools of Medina (Al-Hijaz, now in Saudi Arabia) created the Maliki madhhab, while those in Kufa (now in Iraq) created the Hanafi madhhab.[79] Abu al-Shafi'i, who started as a student of Maliki school of Islamic law, and later was influenced by Hanafi school of Islamic law, disagreed with some of the discretion these schools gave to jurists, and founded the more conservative Shafi'i madhhab, which spread from jurisprudence schools in Baghdad (Iraq) and Cairo (Egypt).[80] Ahmad ibn Hanbal, a student of al-Shafi'i, went further in his criticism of Maliki and Hanafi fiqhs, criticizing the abuse and corruption of Sharia from jurist discretion and consensus of later generation Muslims, and he founded the more strict, traditionalist Hanbali school of Islamic law.[81] Other schools such as the Jariri were established later, which eventually died out.

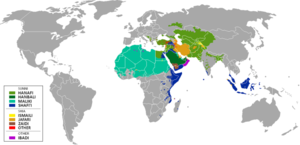

Sunni sect of Islam has four major surviving schools of Sharia: Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanbali, and one minor school named Ẓāhirī; Shii sect of Islam has three: Ja'fari (major), Zaydi and Ismaili.[82][83][84] There are other minority fiqhs as well, such as the Ibadi school of Khawarij sect, and those of Sufi and Ahmadi sects.[74][85] All Sunni and Shia schools of sharia rely first on the Quran and the sayings/practices of Muhammad in the Sunnah. Their differences lie in the procedure each uses to create Islam-compliant laws when those two sources do not provide guidance on a topic.[86] The Salafi movement creates sharia based on the Quran, Sunnah and the actions and sayings of the first three generations of Muslims.[87]

Hanafi-based sharia spread with the patronage and military expansions led by Turkic Sultans and Ottoman Empire in West Asia, Southeast Europe, Central Asia and South Asia.[88] It is currently the largest madhhab of Sunni Muslims.[89] Maliki-based sharia is predominantly found in West Africa, North Africa and parts of Arabia.[89] Shafii-based sharia spread with patronage and military expansions led by maritime Sultans, and is mostly found in coastal regions of East Africa, Arabia, South Asia, Southeast Asia and islands in the Indian ocean.[90] The Hanbali-based sharia prevails in the smallest Sunni madhhab, predominantly found in the Arabian peninsula.[89] The Shia Jafari-based sharia is mostly found in Persian region and parts of West Asia and South Asia.

- Categories of law

- Actions in the fard category are those required of all Muslims. They include the five daily prayers, fasting, articles of faith, obligatory charity, and the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca.[91]

- The mustahabb category includes proper behaviour in matters such as marriage, funeral rites and family life. As such, it covers many of the same areas as civil law in the West. Sharia courts attempt to reconcile parties to disputes in this area using the recommended behaviour as their guide. A person whose behaviour is not mustahabb can be ruled against by the judge.[92]

- All behaviour which is neither discouraged nor recommended, neither forbidden nor required is of the Mubah; it is permissible.[91]

- Makruh behaviour, while it is not sinful of itself, is considered undesirable among Muslims. It may also make a Muslim liable to criminal penalties under certain circumstances.[92]

- Haraam behaviour is explicitly forbidden. It is both sinful and criminal. It includes all actions expressly forbidden in the Quran. Certain Muslim dietary and clothing restrictions also fall into this category.[91]

Areas of Islamic law

The areas of Islamic law include:- Hygiene and purification laws, including the manner of cleansing, either wudhu or ghusl.

- Economic laws, including Zakāt, the annual almsgiving; Waqf, the religious endowment; the prohibition on interest or Riba; as well as inheritance laws.

- Dietary laws including Dhabihah, or ritual slaughter.

- Theological obligations, including the Hajj or pilgrimage, with its rituals such as Tawaf, Sa'yee and the Stoning of the Devil; salat, formal worship; Salat al-Janazah, the funeral prayer; and celebrating Eid al-Adha.

- Marital jurisprudence, including Nikah, the marriage contract; and divorce, known as Khula if initiated by a woman.

- Criminal jurisprudence, including Hudud, fixed punishments; Tazir, discretionary punishment; Qisas or retaliation; Diyya or blood money; and apostasy.

- Military jurisprudence, including Jihad, offensive and defensive; Hudna or truce; and rules regarding prisoners of war.

- Dress code, including hijab.

- Other topics include customs and behaviour, slavery and the status of non-Muslims.

- Other classifications

"Reliance of the Traveller", an English translation of a fourteenth-century CE reference on the Shafi'i school of fiqh written by Ahmad ibn Naqib al-Misri, organizes sharia law into the following topics: Purification, prayer, funeral prayer, taxes, fasting, pilgrimage, trade, inheritance, marriage, divorce and justice.

In some areas, there are substantial differences in the law between different schools of fiqh, countries, cultures and schools of thought.

Application

Application by country

Most Muslim-majority countries with sharia-prescribed hudud punishments in their legal code, do not prescribe it routinely and use other punishments instead.[95][101] The harshest sharia penalties such as stoning, beheading and the death penalty are enforced with varying levels of consistency.[102]

Since 1970s, most Muslim-majority countries have faced vociferous demands from their religious groups and political parties for immediate adoption of Sharia as the sole, or at least primary legal framework.[103] Some moderates and liberal scholars within these Muslim countries have argued for limited expansion of sharia.[104]

With increasing immigration into Europe, there have been allegations of "no-go zones" being established where sharia law reigns supreme.[105][106] However, the existence of "no-go zones" has been denied by European leaders, and it is shown that anti-immigrant groups falsely equate low-income neighborhoods predominantly inhabited by immigrants as "no-go zones." [107][108]

Enforcement

Sharia is enforced in Islamic nations in a number of ways, including mutaween and hisbah.The mutaween (Arabic: المطوعين، مطوعية muṭawwiʿīn, muṭawwiʿiyyah)[109] are the government-authorized or government-recognized religious police (or clerical police) of Saudi Arabia. Elsewhere, enforcement of Islamic values in accordance with Sharia is the responsibility of Polisi Perda Syariah Islam in Aceh province of Indonesia,[110] Committee for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice (Gaza Strip) in parts of Palestine, and Basiji Force in Iran.[111]

Official from the Department of Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, beating a woman in Afghanistan for violating local interpretation of sharia.[112][113]

Hisbah (Arabic: حسبة ḥisb(ah), or hisba) is a historic Islamic doctrine which means "accountability".[114] Hisbah doctrine holds that it is a religious obligation of every Muslim that he or she report to the ruler (Sultan, government authorities) any wrong behavior of a neighbor or relative that violates sharia or insults Islam. The doctrine states that it is the divinely sanctioned duty of the ruler to intervene when such charges are made, and coercively "command right and forbid wrong" in order to keep everything in order according to sharia.[115][116][117] Some Salafist suggest that enforcement of sharia under the Hisbah doctrine is the sacred duty of all Muslims, not just rulers.[115] The doctrine of Hisbah in Islam has traditionally allowed any Muslim to accuse another Muslim, ex-Muslim or non-Muslim for beliefs or behavior that may harm Islamic society. This principle has been used in countries such as Egypt, Pakistan and others to bring blasphemy charges against apostates.[118] For example, in Egypt, sharia was enforced on the Muslim scholar Nasr Abu Zayd, through the doctrine of Hasbah, when he committed apostasy.[119][120] Similarly, in Nigeria, after twelve northern Muslim-majority states such as Kano adopted sharia-based penal code between 1999 and 2000, hisbah became the allowed method of sharia enforcement, where all Muslim citizens could police compliance of moral order based on sharia.[121] In Aceh province of Indonesia, Islamic vigilante activists have invoked Hasbah doctrine to enforce sharia on fellow Muslims as well as demanding non-Muslims to respect sharia.[122] Hisbah has been used in many Muslim majority countries, from Morocco to Egypt and in West Asia to enforce sharia restrictions on blasphemy and criticism of Islam over internet and social media.[123][124][125]

Legal and court proceedings

Sharia judicial proceedings have significant differences from other legal traditions, including those in both common law and civil law. Sharia courts traditionally do not rely on lawyers; plaintiffs and defendants represent themselves. Trials are conducted solely by the judge, and there is no jury system. There is no pre-trial discovery process, and no cross-examination of witnesses. Unlike common law, judges' verdicts do not set binding precedents[126][127] under the principle of stare decisis,[128] and unlike civil law, sharia is left to the interpretation in each case and has no formally codified universal statutes.[129]The rules of evidence in sharia courts also maintain a distinctive custom of prioritizing oral testimony.[130] Witnesses, in a sharia court system, must be faithful, that is Muslim.[131] Male Muslim witnesses are deemed more reliable than female Muslim witnesses, and non-Muslim witnesses considered unreliable and receive no priority in a sharia court.[132][133] In civil cases, a Muslim woman witness is considered half the worth and reliability than a Muslim man witness.[134][135] In criminal cases, women witnesses are unacceptable in stricter, traditional interpretations of sharia, such as those found in Hanbali madhhab.[131]

- Criminal cases

Testimony must be from at least two free Muslim male witnesses, or one Muslim male and two Muslim females, who are not related parties and who are of sound mind and reliable character. Testimony to establish the crime of adultery, fornication or rape must be from four Muslim male witnesses, with some fiqhs allowing substitution of up to three male with six female witnesses; however, at least one must be a Muslim male.[139] Forensic evidence (i.e., fingerprints, ballistics, blood samples, DNA etc.) and other circumstantial evidence is likewise rejected in hudud cases in favor of eyewitnesses, a practice which can cause severe difficulties for women plaintiffs in rape cases.[140][141]

Muslim jurists have debated whether and when coerced confession and coerced witnesses are acceptable. The majority opinion of jurists in the Hanafi madhhab, for example, ruled that torture to get evidence is acceptable and such evidence is valid, but a 17th-century text by Hanafi jurist Muhammad Shaykhzade argued that coerced confession should be invalid; Shaykhzade acknowledged that beating to get confession has been authorized in fatwas by many Islamic jurists.[142]

- Civil cases

In commercial and civil contracts, such as those relating to exchange of merchandise, agreement to supply or purchase goods or property, and others, oral contracts and the testimony of Muslim witnesses triumph over written contracts. Sharia system has held that written commercial contracts may be forged.[145][146] Timur Kuran states that the treatment of written evidence in religious courts in Islamic regions created an incentive for opaque transactions, and the avoidance of written contracts in economic relations. This led to a continuation of a "largely oral contracting culture" in Muslim nations and communities.[146][147]

In lieu of written evidence, oaths are accorded much greater weight; rather than being used simply to guarantee the truth of ensuing testimony, they are themselves used as evidence. Plaintiffs lacking other evidence to support their claims may demand that defendants take an oath swearing their innocence, refusal thereof can result in a verdict for the plaintiff.[148] Taking an oath for Muslims can be a grave act; one study of courts in Morocco found that lying litigants would often "maintain their testimony 'right up to the moment of oath-taking and then to stop, refuse the oath, and surrender the case."[149] Accordingly, defendants are not routinely required to swear before testifying, which would risk casually profaning the Quran should the defendant commit perjury;[149] instead oaths are a solemn procedure performed as a final part of the evidence process.

- Sentencing

Saudi Arabia follows Hanbali sharia, whose historic jurisprudence texts considered a Christian or Jew life as half the worth of a Muslim. Jurists of other schools of law in Islam have ruled differently. For example, Shafi'i sharia considers a Christian or Jew life as a third the worth of a Muslim, and Maliki's sharia considers it worth half.[152] The legal schools of Hanafi, Maliki and Shafi'i Sunni Islam as well as those of Shia Islam have considered the life of polytheists and atheists as one-fifteenth the value of a Muslim during sentencing.[152]

Support

A 2013 survey based on the opinion of 38,000 individuals by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life found that support for making sharia the official law of the land is very high in many Muslim-majority Islamic countries.[156] A majority of Muslims favor sharia as the law of land in Afghanistan (99%), Iraq (91%), Niger (86%), Malaysia (86%), Pakistan (84%), Morocco (83%), Bangladesh (82%), Egypt (74%), Indonesia (72%), Jordan (71%), Uganda (66%), Ethiopia (65%), Mali (63%), Ghana (58%), and Tunisia (56%).[157] Among regional Muslim populations elsewhere, significant percentage favored sharia law: Nigeria (71%), Russia (42%), Kyrgyzstan (35%), Lebanon (29%), Kosovo (20%), Tanzania (37%).[156] In Muslim-majority countries such as Egypt, Jordan, Afghanistan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Lebanon and Turkey, 40% to 74% of Muslims wanted sharia law to apply to non-Muslims as well.[156] A 2008 YouGov poll in the United Kingdom found 40% of Muslims interviewed wanted sharia in British law.[158]

Since the 1970s, the Islamist movements have become prominent; their goals are the establishment of Islamic states and sharia not just within their own borders; their means are political in nature. The Islamist power base is the millions of poor, particularly urban poor moving into the cities from the countryside. They are not international in nature (one exception being the Muslim Brotherhood). Their rhetoric opposes western culture and western power.[159] Political groups wishing to return to more traditional Islamic values are the source of threat to Turkey's secular government.[159] These movements can be considered neo-Sharism.[160]

Extremism

Fundamentalists, wishing to return to basic Islamic religious values and law, have in some instances imposed harsh sharia punishments for crimes, curtailed civil rights and violated human rights.Extremists have used the Quran and their own particular version of sharia to justify acts of war and terror against Muslim as well as non-Muslim individuals and governments, using alternate, conflicting interpretations of Sharia and their notions of jihad.[161][162]

The Sharia basis of arguments of those advocating terrorism, however, remain controversial. Some scholars state that Islamic law prohibits the killing of civilian non-combatants; in contrast, others interpret Islamic law differently, concluding that all means are legitimate to reach their aims, including targeting Muslim non-combatants and the mass killing of non-Muslim civilians, in order to universalize Islam.[161] Islam, in these interpretations, "does not make target differences between militaries and civilians but between Muslims and unbelievers. Therefore it is legitimated (sic) to spill civilians’ blood".[161] Other scholars of Islam, interpret Sharia differently, stating, according to Engeland-Nourai, "attacking innocent people is not courageous; it is stupid and will be punished on the Day of Judgment [...]. It’s not courageous to attack innocent children, women and civilians. It is courageous to protect freedom; it is courageous to defend one and not to attack".[161][163]

Criticism

Compatibility with democracy

Sharia law involves elements of a democratic system, namely electoral procedure, though dispute as to what a "democracy" constitutes leaves this in question.[164] Legal scholar L. Ali Khan argues that "constitutional orders founded on the principles of sharia are fully compatible with democracy, provided that religious minorities are protected and the incumbent Islamic leadership remains committed to the right to recall".[165][166]However, many courts have generally ruled against the implementation of Sharia law, both in jurisprudence and within a community context, based on Sharia's religious background. Whereas groups within a number of nations are actively seeking to implement Sharia law, in 1998 the Constitutional Court of Turkey banned and dissolved Turkey's Refah Party on the grounds that "Democracy is the antithesis of Sharia", the latter of which Refah sought to introduce.[167][168]

On appeal by Refah the European Court of Human Rights determined that "sharia is incompatible with the fundamental principles of democracy".[169][170][171] Refah's sharia-based notion of a "plurality of legal systems, grounded on religion" was ruled to contravene the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. It was determined that it would "do away with the State's role as the guarantor of individual rights and freedoms" and "infringe the principle of non-discrimination between individuals as regards their enjoyment of public freedoms, which is one of the fundamental principles of democracy".[172]

Human rights

Several major, predominantly Muslim countries criticized the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) for its perceived failure to take into account the cultural and religious context of non-Western countries. Iran claimed that the UDHR was "a secular understanding of the Judeo-Christian tradition", which could not be implemented by Muslims without trespassing the Islamic law. Therefore in 1990 the Organisation of the Islamic Conference, a group representing all Muslim majority nations, adopted the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam.[173][174]Ann Elizabeth Mayer points to notable absences from the Cairo Declaration: provisions for democratic principles, protection for religious freedom, freedom of association and freedom of the press, as well as equality in rights and equal protection under the law. Article 24 of the Cairo declaration states that "all the rights and freedoms stipulated in this Declaration are subject to the Islamic shari'a".[175]

Professor H. Patrick Glenn notes that the European concept of human rights developed in reaction to an entrenched hierarchy of class and privilege contrary to, and rejected by, Islam. As implemented in sharia law, protection for the individual is defined in terms of mutual obligation rather than human rights. The concept of human rights, as applied in the European framework, is therefore unnecessary and potentially destructive to these mutual obligations. By "giving priority to human welfare over human liberty," Islamic law justifies the formal inequality of individuals by collective goals.[176]

Many secularist, human rights, and leading organisations have criticized Saudi Arabia's stance on human rights. In 2009, the journal Free Inquiry summarized this criticism in an editorial: "We are deeply concerned with the changes to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by a coalition of Islamic states within the United Nations that wishes to prohibit any criticism of religion and would thus protect Islam's limited view of human rights. In view of the conditions inside the Islamic Republic of Iran, Egypt, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the Sudan, Syria, Bangdalesh, Iraq, and Afghanistan, we should expect that at the top of their human rights agenda would be to rectify the legal inequality of women, the suppression of political dissent, the curtailment of free expression, the persecution of ethnic minorities and religious dissenters — in short, protecting their citizens from egregious human rights violations. Instead, they are worrying about protecting Islam."[177]

Freedom of speech

Blasphemy in Islam is any form of cursing, questioning or annoying God, Muhammad or anything considered sacred in Islam.[178][179][180] The sharia of various Islamic schools of jurisprudence specify different punishment for blasphemy against Islam, by Muslims and non-Muslims, ranging from imprisonment, fines, flogging, amputation, hanging, or beheading.[178][181][182] In some cases, sharia allows non-Muslims to escape death by converting and becoming a devout follower of Islam.[183]Blasphemy, as interpreted under sharia, is controversial. Muslim nations have petitioned the United Nations to limit "freedom of speech" because "unrestricted and disrespectful opinion against Islam creates hatred".[184] Other nations, in contrast, consider blasphemy laws as violation of "freedom of speech",[185] stating that freedom of expression is essential to empowering both Muslims and non-Muslims, and point to the abuse of blasphemy laws, where hundreds, often members of religious minorities, are being lynched, killed and incarcerated in Muslim nations, on flimsy accusations of insulting Islam.[186][187]

Freedom of thought, conscience and religion

According to the United Nations' the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,[188] every human has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change their religion or belief. Sharia has been criticized for not recognizing this human right. According to scholars[15][189][190] of traditional Islamic law, the applicable rules for religious conversion under Sharia are as follows:- If a person converts to Islam, or is born and raised as a Muslim, then he or she will have full rights of citizenship in an Islamic state.[191]

- Leaving Islam is a sin and a religious crime. Once any man or woman is officially classified as Muslim, because of birth or religious conversion, he or she will be subject to the death penalty if he or she becomes an apostate, that is, abandons his or her faith in Islam in order to become an atheist, agnostic or to convert to another religion. Before executing the death penalty, Sharia demands that the individual be offered one chance to return to Islam.[191]

- If a person has never been a Muslim, and is not a kafir (infidel, unbeliever), he or she can live in an Islamic state by accepting to be a dhimmi, or under a special permission called aman. As a dhimmi or under aman, he or she will suffer certain limitations of rights as a subject of an Islamic state, and will not enjoy complete legal equality with Muslims.[191]

- If a person has never been a Muslim, and is a kafir (infidel, unbeliever), Sharia demands that he or she should be offered the choice to convert to Islam and become a Muslim; if they reject the offer, he or she may either be killed, enslaved, or ransomed if captured.[191]

Some scholars claim that Sharia allows religious freedom because a Shari'a verse teaches, "there is no compulsion in religion."[200] Others scholars claim Sharia recognizes only one proper religion, considers apostasy as sin punishable with death, and members of other religions as kafir (infidel);[201] or hold that Shari'a demands that all apostates and kafir must be put to death, enslaved or be ransomed.[202][203][204][205] Yet other scholars suggest that Shari'a has become a product of human interpretation and inevitably leads to disagreements about the “precise contents of the Shari'a." In the end, then, what is being applied is not Sharia, but what a particular group of clerics and government decide is Sharia. It is these differing interpretations of Shari'a that explain why many Islamic countries have laws that restrict and criminalize apostasy, proselytism and their citizens' freedom of conscience and religion.[206][207]

LGBT rights

Homosexual intercourse is illegal under sharia law, though the prescribed penalties differ from one school of jurisprudence to another. For example, only a few Muslim-majority countries impose the death penalty for acts perceived as sodomy and homosexual activities: Iran,[208] Saudi Arabia,[209] and Somalia.[210] In other Muslim-majority countries such as Egypt, Iraq, and the Indonesian province of Aceh,[211] same-sex sexual acts are illegal,[212] and LGBT people regularly face violence and discrimination.[213] In Turkey, Bahrain and Jordan, homosexual acts between consenting individuals are legal.[citation needed] There is a new movement of LGBT Muslims, particularly in Jordan, the UK with Imaan and Al-Fatiha in America.[citation needed] Books such as Islam and Homosexuality by Siraj Scott has also contributed to playing a proactive role in LGBT- and Islam-related ideas.[original research?]Women

Domestic violence

Many scholars[16][214] claim Shari'a law encourages domestic violence against women, when a husband suspects nushuz (disobedience, disloyalty, rebellion, ill conduct) in his wife.[215] Other scholars claim wife beating, for nashizah, is not consistent with modern perspectives of the Quran.[216]One of the verses of the Quran relating to permissibility of domestic violence is Surah 4:34.[217][218] In deference to Surah 4:34, many nations with Shari'a law have refused to consider or prosecute cases of domestic abuse.[219][220][221][222] Shari'a has been criticized for ignoring women's rights in domestic abuse cases.[223][224][225][226] Musawah/CEDAW, KAFA and other organizations have proposed ways to modify Shari'a-inspired laws to improve women's rights in Islamic nations, including women's rights in domestic abuse cases.[227][228][229][230]

Personal status laws and child marriage

Shari'a is the basis for personal status laws in most Islamic majority nations. These personal status laws determine rights of women in matters of marriage, divorce and child custody. A 2011 UNICEF report concludes that Shari'a law provisions are discriminatory against women from a human rights perspective. In legal proceedings under Shari'a law, a woman’s testimony is worth half of a man’s before a court.[134]Except for Iran, Lebanon and Bahrain which allow child marriages, the civil code in Islamic majority countries do not allow child marriage of girls. However, with Shari'a personal status laws, Shari'a courts in all these nations have the power to override the civil code. The religious courts permit girls less than 18 years old to marry. As of 2011, child marriages are common in a few Middle Eastern countries, accounting for 1 in 6 all marriages in Egypt and 1 in 3 marriages in Yemen. However, the average age at marriage in most Middle Eastern countries is steadily rising and is generally in the low to mid 20's for women.[231] Rape is considered a crime in all countries, but Shari'a courts in Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Libya, Morocco, Syria and Tunisia in some cases allow a rapist to escape punishment by marrying his victim, while in other cases the victim who complains is often prosecuted with the Sharia crime of Zina (adultery).[134][232][233]

Women's right to property and consent

Sharia grants women the right to inherit property from other family members, and these rights are detailed in the Quran.[234] A woman's inheritance is unequal and less than a man's, and dependent on many factors.[Quran 4:12][235] For instance, a daughter's inheritance is usually half that of her brother's.[Quran 4:11][235]Until the 20th century, Islamic law granted Muslim women certain legal rights, such as the right to own property received as Mahr (brideprice) at her marriage, that Western legal systems did not grant to women.[236][237] However, Islamic law does not grant non-Muslim women the same legal rights as the few it did grant Muslim women. Sharia recognizes the basic inequality between master and women slave, between free women and slave women, between Believers and non-Believers, as well as their unequal rights.[238][239] Sharia authorized the institution of slavery, using the words abd (slave) and the phrase ma malakat aymanukum ("that which your right hand owns") to refer to women slaves, seized as captives of war.[238][240] Under Islamic law, Muslim men could have sexual relations with female captives and slaves without her consent.[241][242]

Slave women under Sharia did not have a right to own property, right to free movement or right to consent.[243][244] Sharia, in Islam's history, provided religious foundation for enslaving non-Muslim women (and men), as well as encouraged slave's manumission. However, manumission required that the non-Muslim slave first convert to Islam.[245][246] Non-Muslim slave women who bore children to their Muslim masters became legally free upon her master's death, and her children were presumed to be Muslims as their father, in Africa,[245] and elsewhere.[247]

Starting with the 20th century, Western legal systems evolved to expand women's rights, but women's rights under Islamic law have remained tied to Quran, hadiths and their faithful interpretation as Sharia by Islamic jurists.[242][248]

Parallels with Western legal systems

Elements of Islamic law have influenced western legal systems. As example, the influence of Islamic influence on the development of an international law of the sea" can be discerned alongside that of the Roman influence.[249]Makdisi states Islamic law also influenced the legal scholastic system of the West.[250] The study of legal text and degrees have parallels between Islamic studies of sharia and the Western system of legal studies. For example, the status of faqih (meaning "master of law"), mufti (meaning "professor of legal opinions") and mudarris (meaning "teacher"), which were later translated into Latin as magister, professor and doctor respectively.[250]

There are differences between Islamic and Western legal systems. For example, Sharia classically recognizes only natural persons, and never developed the concept of a legal person, or corporation, i.e., a legal entity that limits the liabilities of its managers, shareholders, and employees; exists beyond the lifetimes of its founders; and that can own assets, sign contracts, and appear in court through representatives.[251] Interest prohibitions also imposed secondary costs by discouraging record keeping, and delaying the introduction of modern accounting.[252] Such factors, according to Timur Kuran, have played a significant role in retarding economic development in the Middle East.[253]