People often conform from a desire for security within a

group—typically a group of a similar age, culture, religion, or

educational status. This is often referred to as groupthink:

a pattern of thought characterized by self-deception, forced

manufacture of consent, and conformity to group values and ethics, which

ignores realistic appraisal of other courses of action. Unwillingness

to conform carries the risk of social rejection. Conformity is often associated with adolescence and youth culture, but strongly affects humans of all ages.

Although peer pressure may manifest negatively, conformity can be regarded as either good or bad. Driving on the correct side of the road could be seen as beneficial conformity. With the right environmental influence, conforming, in early childhood years, allows one to learn and thus, adopt the appropriate behaviors necessary to interact and develop correctly within one's society. Conformity influences formation and maintenance of social norms, and helps societies function smoothly and predictably via the self-elimination of behaviors seen as contrary to unwritten rules. In this sense it can be perceived as a positive force that prevents acts that are perceptually disruptive or dangerous.

As conformity is a group phenomenon, factors such as group size, unanimity, cohesion, status, prior commitment and public opinion help determine the level of conformity an individual displays.

Although peer pressure may manifest negatively, conformity can be regarded as either good or bad. Driving on the correct side of the road could be seen as beneficial conformity. With the right environmental influence, conforming, in early childhood years, allows one to learn and thus, adopt the appropriate behaviors necessary to interact and develop correctly within one's society. Conformity influences formation and maintenance of social norms, and helps societies function smoothly and predictably via the self-elimination of behaviors seen as contrary to unwritten rules. In this sense it can be perceived as a positive force that prevents acts that are perceptually disruptive or dangerous.

As conformity is a group phenomenon, factors such as group size, unanimity, cohesion, status, prior commitment and public opinion help determine the level of conformity an individual displays.

Peer

Some adolescents gain acceptance and recognition from their peers by conformity.

This peer moderated conformity increases from the transition of childhood to adolescence.

Social responses

According

to Donelson Forsyth, after submitting to group pressures, individuals

may find themselves facing one of several responses to conformity. These

types of responses to conformity vary in their degree of public

agreement versus private agreement.

When an individual finds themselves in a position where they

publicly agree with the group's decision yet privately disagrees with

the group's consensus, they are experiencing compliance or acquiescence. In turn, conversion, otherwise known as private acceptance,

involves both publicly and privately agreeing with the group's

decision. Thus, this represents a true change of opinion to match the

majority.

Another type of social response, which does not involve conformity with the majority of the group, is called convergence.

In this type of social response, the group member agrees with the

group's decision from the outset and thus does not need to shift their

opinion on the matter at hand.

In addition, Forsyth shows that nonconformity can also fall into

one of two response categories. Firstly, an individual who does not

conform to the majority can display independence. Independence, or dissent,

can be defined as the unwillingness to bend to group pressures. Thus,

this individual stays true to his or her personal standards instead of

the swaying toward group standards. Secondly, a nonconformist could be

displaying anticonformity or counterconformity which

involves the taking of opinions that are opposite to what the group

believes. This type of nonconformity can be motivated by a need to rebel

against the status quo instead of the need to be accurate in one's

opinion.

To conclude, social responses to conformity can be seen to vary

along a continuum from conversion to anticonformity. For example, a

popular experiment in conformity research, known as the Asch situation or Asch conformity experiments, primarily includes compliance and independence. Also, other responses to conformity can be identified in groups such as juries, sports teams and work teams.

Main experiments

Sherif's experiment (1936)

Muzafer

Sherif was interested in knowing how many people would change their

opinions to bring them in line with the opinion of a group. In his

experiment, participants were placed in a dark room and asked to stare

at a small dot of light 15 feet away. They were then asked to estimate

the amount it moved. The trick was there was no movement, it was caused

by a visual illusion known as the autokinetic effect.

On the first day, each person perceived different amounts of movement,

but from the second to the fourth day, the same estimate was agreed on

and others conformed to it.

Sherif suggested this was a simulation for how social norms develop in a

society, providing a common frame of reference for people.

Subsequent experiments were based on more realistic situations.

In an eyewitness identification task, participants were shown a suspect

individually and then in a lineup of other suspects. They were given one

second to identify him, making it a difficult task. One group was told

that their input was very important and would be used by the legal

community. To the other it was simply a trial. Being more motivated to

get the right answer increased the tendency to conform. Those who wanted

to be more accurate conformed 51% of the time as opposed to 35% in the

other group.

Asch's experiment (1951)

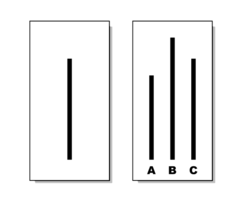

Which line matches the first line, A, B, or C? In the Asch conformity experiments, people frequently followed the majority judgment, even when the majority was wrong.

Solomon E. Asch conducted a modification of Sherif’s study, assuming

that when the situation was very clear, conformity would be drastically

reduced. He exposed people in a group to a series of lines, and the

participants were asked to match one line with a standard line. All

participants except one were accomplices and gave the wrong answer in 12

of the 18 trials.

The results showed a surprisingly high degree of conformity: 74%

of the participants conformed on at least one trial. On average people

conformed one third of the time. A question is how the group would affect individuals in a situation where the correct answer is less obvious.

After his first test, Asch wanted to investigate whether the size

or unanimity of the majority had greater influence on test subjects.

"Which aspect of the influence of a majority is more important – the

size of the majority or its unanimity? The experiment was modified to

examine this question. In one series the size of the opposition was

varied from one to 15 persons."

The results clearly showed that as more people opposed the subject, the

subject became more likely to conform. However, the increasing majority

was only influential up to a point: from three or more opponents, there

is more than 30% of conformity.

Varieties

Harvard psychologist Herbert Kelman identified three major types of conformity.

- Compliance is public conformity, while possibly keeping one's own original beliefs for yourself. Compliance is motivated by the need for approval and the fear of being rejected.

- Identification is conforming to someone who is liked and respected, such as a celebrity or a favorite uncle. This can be motivated by the attractiveness of the source, and this is a deeper type of conformism than compliance.

- Internalization is accepting the belief or behavior and conforming both publicly and privately, if the source is credible. It is the deepest influence on people and it will affect them for a long time.

Although Kelman's distinction has been influential, research in social psychology has focused primarily on two varieties of conformity. These are informational conformity, or informational social influence, and normative conformity, also called normative social influence.

In Kelman's terminology, these correspond to internalization and

compliance, respectively. There are naturally more than two or three

variables in society influential on human psychology

and conformity; the notion of "varieties" of conformity based upon

"social influence" is ambiguous and indefinable in this context.

For Deutsch and Gérard (1955), conformity results from a

motivational conflict (between the fear of being socially rejected and

the wish to say what we think is correct) that leads to the normative

influence, and a cognitive conflict (others create doubts in what we

think) which leads to the informational influence.

Informational influence

Informational social influence occurs when one turns to the members

of one's group to obtain and accept accurate information about reality. A

person is most likely to use informational social influence in certain

situations: when a situation is ambiguous, people become uncertain about

what to do and they are more likely to depend on others for the answer;

and during a crisis when immediate action is necessary, in spite of

panic. Looking to other people can help ease fears, but unfortunately

they are not always right. The more knowledgeable a person is, the more

valuable they are as a resource. Thus people often turn to experts

for help. But once again people must be careful, as experts can make

mistakes too. Informational social influence often results in internalization or private acceptance, where a person genuinely believes that the information is right.

Normative influence

Normative social influence occurs when one conforms to be liked or

accepted by the members of the group. This need of social approval and

acceptance is part of our state of humans.

In addition to this, we know that when people do not conform with their

group and therefore are deviants, they are less liked and even punished

by the group. Normative influence usually results in public compliance, doing or saying something without believing in it. The experiment of Asch in 1951 is one example of normative influence.

In a reinterpretation of the original data from these experiments Hodges and Geyer (2006)

found that Asch's subjects were not so conformist after all: The

experiments provide powerful evidence for people's tendency to tell the

truth even when others do not. They also provide compelling evidence of

people's concern for others and their views.

By closely examining the situation in which Asch's subjects find

themselves they find that the situation places multiple demands on

participants: They include truth (i.e., expressing one's own view

accurately), trust (i.e., taking seriously the value of others' claims),

and social solidarity (i.e., a commitment to integrate the views of

self and others without deprecating either). In addition to these

epistemic values, there are multiple moral claims as well: These include

the need for participants to care for the integrity and well-being of

other participants, the experimenter, themselves, and the worth of

scientific research.

Deutsch & Gérard (1955) designed different situations that

variated from Asch' experiment and found that when participants were

writing their answer privately, they were giving the correct one.

Normative influence, a function of social impact theory, has three components. The number of people in the group has a surprising effect. As the number increases, each person has less of an impact. A group's strength is how important the group is to a person. Groups we value generally have more social influence. Immediacy

is how close the group is in time and space when the influence is

taking place. Psychologists have constructed a mathematical model using

these three factors and are able to predict the amount of conformity

that occurs with some degree of accuracy.

Baron and his colleagues conducted a second eyewitness study

that focused on normative influence. In this version, the task was

easier. Each participant had five seconds to look at a slide instead of

just one second. Once again, there were both high and low motives to be

accurate, but the results were the reverse of the first study. The low

motivation group conformed 33% of the time (similar to Asch's findings).

The high motivation group conformed less at 16%. These results show

that when accuracy is not very important, it is better to get the wrong

answer than to risk social disapproval.

An experiment using procedures similar to Asch's found that there was significantly less conformity in six-person groups of friends as compared to six-person groups of strangers.

Because friends already know and accept each other, there may be less

normative pressure to conform in some situations. Field studies on

cigarette and alcohol abuse, however, generally demonstrate evidence of

friends exerting normative social influence on each other.

Minority influence

Although conformity generally leads individuals to think and act more

like groups, individuals are occasionally able to reverse this tendency

and change the people around them. This is known as minority influence,

a special case of informational influence. Minority influence is most

likely when people can make a clear and consistent case for their point

of view. If the minority fluctuates and shows uncertainty, the chance of

influence is small. However, a minority that makes a strong, convincing

case increases the probability of changing the majority's beliefs and

behaviors.

Minority members who are perceived as experts, are high in status, or

have benefited the group in the past are also more likely to succeed.

Another form of minority influence can sometimes override

conformity effects and lead to unhealthy group dynamics. A 2007 review

of two dozen studies by the University of Washington found that a single

"bad apple" (an inconsiderate or negligent group member) can

substantially increase conflicts and reduce performance in work groups.

Bad apples often create a negative emotional climate that interferes

with healthy group functioning. They can be avoided by careful selection

procedures and managed by reassigning them to positions that require

less social interaction.

Specific predictors

Culture

Stanley Milgram

found that individuals in Norway (from a collectivistic culture)

exhibited a higher degree of conformity than individuals in France (from

an individualistic culture).

Similarly, Berry studied two different populations: the Temne

(collectivists) and the Inuit (individualists) and found that the Temne

conformed more than the Inuit when exposed to a conformity task.

Bond and Smith compared 134 studies in a meta-analysis and found

that there is a positive correlation between a country's level of

collectivist values and conformity rates in the Asch paradigm. Bond and Smith also reported that conformity has declined in the United States over time.

Influenced by the writings of late-19th- and early-20th-century

Western travelers, scholars or diplomats who visited Japan, such as Basil Hall Chamberlain, George Trumbull Ladd and Percival Lowell, as well as by Ruth Benedict's influential book The Chrysanthemum and the Sword,

many scholars of Japanese studies speculated that there would be a

higher propensity to conform in Japanese culture than in American

culture. However, this view was not formed on the basis of empirical evidence collected in a systematic way, but rather on the basis of anecdotes and casual observations, which are subject to a variety of cognitive biases.

Modern scientific studies comparing conformity in Japan and the United

States show that Americans conform in general as much than the Japanese

and, in some situations, even more. Psychology professor Yohtaro Takano from the University of Tokyo,

along with Eiko Osaka reviewed four behavioral studies and found that

the rate of conformity errors that the Japanese subjects manifested in

the Asch paradigm was similar with that manifested by Americans. The study published in 1970 by Robert Frager from the University of California, Santa Cruz

found that the percentage of conformity errors within Asch paradigm was

significantly lower in Japan than in the United States, especially in

the prize condition. Another study published in 2008, which compared the

level of conformity among Japanese in-groups (peers from the same

college clubs) with that found among Americans found no substantial

difference in the level of conformity manifested by the two nations,

even in the case of in-groups.

Gender

Societal

norms often establish gender differences and researchers have reported

differences in the way men and women conform to social influence.

For example, Alice Eagly and Linda Carli performed a meta-analysis of

148 studies of influenceability. They found that women are more

persuadable and more conforming than men in group pressure situations

that involve surveillance. Eagly has proposed that this sex difference may be due to different sex roles in society. Women are generally taught to be more agreeable whereas men are taught to be more independent.

The composition of the group plays a role in conformity as well.

In a study by Reitan and Shaw, it was found that men and women conformed

more when there were participants of both sexes involved versus

participants of the same sex. Subjects in the groups with both sexes

were more apprehensive when there was a discrepancy amongst group

members, and thus the subjects reported that they doubted their own

judgments.

Sistrunk and McDavid made the argument that women conformed more because of a methodological bias.

They argued that because stereotypes used in studies are generally male

ones (sports, cars..) more than female ones (cooking, fashion..), women

are feeling uncertain and conformed more, which was confirmed by their

results.

Age

Research has

noted age differences in conformity. For example, research with

Australian children and adolescents ages 3 to 17 discovered that

conformity decreases with age. Another study examined individuals that were ranged from ages 18 to 91. The results revealed a similar trend – older participants displayed less conformity when compared to younger participants.

In the same way that gender has been viewed as corresponding to

status, age has also been argued to have status implications. Berger,

Rosenholtz and Zelditch suggest that age as a status role can be

observed among college students. Younger students, such as those in

their first year in college, are treated as lower-status individuals and

older college students are treated as higher-status individuals.

Therefore, given these status roles, it would be expected that younger

individuals (low status) conform to the majority whereas older

individuals (high status) would be expected not to conform.

Researchers have also reported an interaction of gender and age on conformity.

Eagly and Chrvala examined the role of age (under 19 years vs. 19 years

and older), gender and surveillance (anticipating responses to be

shared with group members vs. not anticipating responses being shared)

on conformity to group opinions. They discovered that among participants

that were 19 years or older, females conformed to group opinions more

so than males when under surveillance (i.e., anticipated that their

responses would be shared with group members). However, there were no

gender differences in conformity among participants who were under 19

years of age and in surveillance conditions. There were also no gender

differences when participants were not under surveillance. In a

subsequent research article, Eagly suggests that women are more likely

to conform than men because of lower status roles of women in society.

She suggests that more submissive roles (i.e., conforming) are expected

of individuals that hold low status roles.

Still, Eagly and Chrvala's results do conflict with previous research

which have found higher conformity levels among younger rather than

older individuals.

Size of the group

Although

conformity pressures generally increase as the size of the majority

increases, a meta-analysis suggests that conformity pressures in Asch's

experiment peak once the majority reaches about four or five in number. Moreover, a study suggests that the effects of group size depend on the type of social influence operating.

This means that in situations where the group is clearly wrong,

conformity will be motivated by normative influence; the participants

will conform in order to be accepted by the group. A participant may not

feel much pressure to conform when the first person gives an incorrect

response. However, conformity pressure will increase as each additional

group member also gives the same incorrect response.

Different stimuli

In

1961 Stanley Milgram published a study in which he utilized Asch's

conformity paradigm using audio tones instead of lines; he conducted his

study in Norway and France.

He found substantially higher levels of conformity than Asch, with

participants conforming 50% of the time in France and 62% of the time in

Norway during critical trials. Milgram also conducted the same

experiment once more, but told participants that the results of the

study would be applied to the design of aircraft safety signals. His

conformity estimates were 56% in Norway and 46% in France, suggesting

that individuals conformed slightly less when the task was linked to an

important issue. Stanley Milgram's study demonstrated that Asch's study

could be replicated with other stimuli, and that in the case of tones,

there was a high degree of conformity.

Neural correlates

Evidence has been found for the involvement of the posterior medial frontal cortex (pMFC) in conformity, an area associated with memory and decision-making. For example, Klucharev et al. revealed in their study that by using repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

on the pMFC, participants reduced their tendency to conform to the

group, suggesting a causal role for the brain region in social

conformity. In another study, the mPFC was linked to normative social influence, whilst the activity in the caudate was regarded as an index of informational influence.

The amygdala and hippocampus

have also been found to be recruited when individuals participated in a

social manipulation experiment involving long-term memory. Several other areas have further been suggested to play a role in conformity, including the insula, the temporoparietal junction, the ventral striatum, and the anterior and posterior cingulate cortices.

More recent work stresses the role of orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) in conformity not only at the time of social influence,

but also later on, when participants are given an opportunity to

conform by selecting an action. In particular, Charpentier et al. found

that the OFC mirrors the exposure to social influence at a subsequent

time point, when a decision is being made without the social influence

being present. The tendency to conform has also been observed in the

structure of the OFC, with a greater grey matter volume in high conformers.