Journalism in America began as a "humble" affair and became a political force in the campaign for American independence. Following independence, the first article of U.S. Constitution guaranteed freedom of the press and speech and the American press grew rapidly following the American Revolution. The press became a key support element to the country's political parties but also organized religious institutions.

Journalist Marguerite Martyn of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch made this sketch of herself interviewing a Methodist minister in 1908 for his views on marriage.

During the 19th century, newspapers began to expand and appear outside eastern U.S. cities. From the 1830s onward the penny press

began to play a major role in American journalism and technological

advancements such as the telegraph and faster printing presses in the

1840s helped expand the press of the nation as it experienced rapid

economic and demographic growth.

By 1900 major newspapers had become profitable powerhouses of advocacy, muckraking and sensationalism, along with serious, and objective news-gathering. In the early 20th century, before television, the average American read several newspapers per day. Starting in the 1920s changes in technology again morphed the nature of American journalism as radio and later, television, began to play increasingly important roles.

In the late 20th century, much of American journalism merged into big media conglomerates (principally owned by media moguls, Ted Turner and Rupert Murdoch).

With the coming of digital journalism in the 21st Century, newspapers

faced a business crisis as readers turned to the internet for news and

advertisers followed them.

Origins

The history of American journalism began in 1690, when Benjamin Harris

published the first edition of "Publick Occurrences, Both Foreign and

Domestic" in Boston. Harris had strong trans-Atlantic connections and

intended to publish a regular weekly newspaper along the lines of those

in London, but he did not get prior approval and his paper was

suppressed after a single edition. The first successful newspaper, The Boston News-Letter,

was launched in 1704. This time, the founder was John Campbell, the

local postmaster, and his paper proclaimed that it was "published by

authority."

As the colonies grew rapidly in the 18th century, newspapers

appeared in port cities along the East Coast, usually started by master

printers seeking a sideline. Among them was James Franklin, founder of The New England Courant (1721-1727), where he employed his younger brother, Benjamin Franklin,

as a printer's apprentice. Like many other colonial newspapers, it was

aligned with party interests. Ben Franklin was first published in his

brother's newspaper, under the pseudonym Silence Dogood

in 1722, and even his brother did not know his identity at first.

Pseudonymous publishing, a common practice of that time, protected

writers from retribution from government officials and others they

criticized, often to the point of what today would be considered libel. The content

included advertising of newly landed products, and locally produced

news items, usually based on commercial and political events. Editors

exchanged their papers and frequently reprinted news from other cities.

Essays and letters to the editor, often anonymous, provided opinions on

current issues. While the religious news was thin, writers typically

interpreted good news in terms of God's favor, and bad news as evidence

of His wrath. The fate of criminals was often cast as cautionary tales

warning of the punishment for sin.

Ben Franklin moved to Philadelphia in 1728 and took over the Pennsylvania Gazette

the following year. Ben Franklin expanded his business by essentially

franchising other printers in other cities, who published their own

newspapers. By 1750, 14 weekly newspapers were published in the six

largest colonies. The largest and most successful of these could be

published up to three times per week.

American Independence

The Stamp Act of 1765 taxed paper, and the burden of the tax fell on printers, who led a successful fight to repeal the tax.

By the early 1770s, most newspapers supported the Patriot cause;

Loyalist newspapers were often forced to shut down or move to Loyalist

strongholds, especially New York City. Publishers up and down the colonies widely reprinted the pamphlets by Thomas Paine, especially "Common Sense" (1776). His Crisis essays first appeared in the newspaper press starting in December, 1776, when he warned:

- These are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country, but he that stands it now deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.

Anne Catherine Hoof Green, publisher of the Maryland Gazette, 1767-1775.

When the war for independence began in 1775, 37 weekly newspapers

were in operation; 20 survived the war, and 33 new ones started up. The

British blockade sharply curtailed imports of paper, ink, and new

equipment; causing thinner newspapers and publication delays. When the

war ended in 1782, there were 35 newspapers with a combined circulation

of about 40,000 copies per week, and an actual readership in the

hundreds of thousands. These newspapers played a major role in defining

the grievances of the colonists against the British government in the

1765-1775 era, and in supporting the American Revolution.

Every week the Maryland Gazette

of Annapolis promoted the Patriot cause and also reflected informed

Patriot viewpoints. From the time of the Stamp Act, publisher Jonas

Green vigorously protested British actions. When he died in 1767, his

widow Anne Catherine Hoof Green became the first woman to hold a top job at an American newspaper.

A strong supporter of colonial rights, she published the newspapers as

well as many pamphlets with the help of two sons; She died in 1775.

During the war, contributors debated disestablishment of the

Anglican church in several states, use of coercion against neutrals and

Loyalists, the meaning of Paine's "Common Sense", and the confiscation

of Loyalist property. Much attention was devoted to the details of

military campaigns, typically with an upbeat optimistic tone.

Patriot editors often sharply criticized government action or

inaction. In peacetime, criticism might lead to a loss of valuable

printing contract, but in wartime, the government needed the newspapers.

Furthermore, there were enough different state governments and

political factions that editors could be protected by their friends.

When Thomas Paine lost his patronage job with Congress because of a

letter he published, the state government soon hired him.

First Party System

Newspapers flourished in the new republic — by 1800, there were about

234 being published — and tended to be very partisan about the form of

the new federal government, which was shaped by successive Federalist or Republican presidencies. Newspapers directed much abuse toward various politicians, and the eventual duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr was fueled by controversy in newspaper pages.

Federalist

poster about 1800. Washington (in heaven) tells partisans to keep the

pillars of Federalism, Republicanism, and Democracy

By 1796, both parties sponsored national networks of weekly newspapers, which attacked each other vehemently. The Federalist and Republican newspapers of the 1790s traded vicious barbs against their enemies.

The most heated rhetoric came in debates over the French Revolution, especially the Jacobin Terror

of 1793–94 when the guillotine was used daily. Nationalism was a high

priority, and the editors fostered an intellectual nationalism typified

by the Federalist effort to stimulate a national literary culture

through their clubs and publications in New York and Philadelphia, and Noah Webster's efforts to simplify and Americanize the language.

Penny press, telegraph, and party politics

As

American cities like New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Washington

grew, so did newspapers. Larger printing presses, the telegraph, and

other technological innovations allowed newspapers to print thousands of

copies, boost circulation, and increase revenue. In the largest cities,

some papers were politically independent. But most, especially in

smaller cities, had close ties political parties, who used them for

communication and campaigning. Their editorials explained the party

position on current issues, and condemned the opposition.

The first newspaper to fit the 20th century style of a newspaper was the New York Herald, founded in 1835 and published by James Gordon Bennett, Sr. It was politically independent, and became the first newspaper to have city staff covering regular beats and spot news,

along with regular business and Wall Street coverage. In 1838 Bennett

also organized the first foreign correspondent staff of six men in

Europe and assigned domestic correspondents to key cities, including the

first reporter to regularly cover Congress.

The leading partisan newspaper was the New York Tribune, which began publishing in 1841 and was edited by Horace Greeley.

It was the first newspaper to gain national prominence; by 1861, it

shipped thousands of copies of its daily and weekly editions to

subscribers. Greeley also organized a professional news staff and

embarked on frequent publishing crusades for causes he believed in. The

Tribune was the first newspaper, in 1886, to use the linotype machine, invented by Ottmar Mergenthaler,

which rapidly increased the speed and accuracy with which type could be

set. it allowed a newspaper to publish multiple editions the same day,

updating the front page with the latest business and sports news.

The New York Times,

now one of the best-known newspapers in the world, was founded in 1851

by George Jones and Henry Raymond. It established the principle of

balanced reporting in high-quality writing. Its prominence emerged in

the 20th century.

Political partisanship

The parties created an internal communications system designed to keep in close touch with the voters.

The critical communications system was a national network of

partisan newspapers. Nearly all weekly and daily papers were party

organs until the early 20th century. Thanks to the invention of

high-speed presses for city papers, and free postage for rural sheets,

newspapers proliferated. In 1850, the Census counted 1,630 party

newspapers (with a circulation of about one per voter), and only 83

"independent" papers. The party line was behind every line of news copy,

not to mention the authoritative editorials, which exposed the

"stupidity" of the enemy and the "triumphs" of the party in every issue.

Editors were senior party leaders and often were rewarded with

lucrative postmasterships. Top publishers, such as Schuyler Colfax in 1868, Horace Greeley in 1872, Whitelaw Reid in 1892, Warren Harding in 1920 and James Cox also in 1920, were nominated on the national ticket.

Kaplan outlines the systematic methods by which newspapers

expressed their partisanship. Paid advertising was unnecessary, as the

party encouraged all its loyal supporters to subscribe:

- Editorials explained in detail the strengths of the party platform, and the weaknesses and fallacies of the opposition.

- As the election neared, there were lists of approved candidates.

- Party meetings, parades, and rallies were publicized ahead of time and reported in depth afterward. Excitement and enthusiasm were exaggerated, while the dispirited enemy rallies were ridiculed.

- Speeches were often transcribed in full detail, even long ones that ran thousands of words.

- Woodcut illustrations celebrated the party symbols and portray the candidates.

- Editorial cartoons ridiculed the opposition and promoted the party ticket.

- As the election neared, predictions and informal polls guaranteed victory.

- The newspapers printed filled-out ballots which party workers distributed on election day so voters could drop them directly into the boxes. Everyone could see who the person voted for.

- The first news reports the next day, often claimed victory – sometimes it was days or weeks before the editor admitted defeat.

By the time of the Civil War, many moderately sized cities had at

least two newspapers, often with very different political perspectives.

As the South began the task of seceding from the Union, some papers in

the North recommended that the South should be allowed to secede. “The

government, however, was not willing to allow 'sedition' to masquerade

(in its opinion) as 'freedom of the press.'” Several newspapers were

closed by government action. After the massive Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run,

angry mobs in the North destroyed substantial property owned by

remaining “successionist” newspapers. Those still in publication

quickly came to support the war, both to avoid mob action and to retain

their audience.

After 1900, William Randolph Hearst, Joseph Pulitzer

and other big city politician-publishers discovered they could make far

more profit through advertising, at so many dollars per thousand

readers. By becoming non-partisan they expanded their base to include

the opposition party and the fast-growing number of consumers who read

the ads but were less and less interested in politics. There was less

political news after 1900, apparently because citizens became more

apathetic, and shared their partisan loyalties with the new professional

sports teams that attracted growing audiences.

Whitelaw Reid, the powerful long-time editor of the Republican New York Tribune, emphasized the importance of partisan newspapers in 1879:

The true statesman and the really influential editor are those who are able to control and guide parties...There is an old question as to whether a newspaper controls public opinion or public opinion controls the newspaper. This at least is true: that editor best succeeds who best interprets the prevailing and the better tendencies of public opinion, and, who, whatever his personal views concerning it, does not get himself too far out of relations to it. He will understand that a party is not an end, but a means; will use it if it leads to his end, -- will use some other if that serve better, but will never commit the folly of attempting to reach the end without the means...Of all the puerile follies that have masqueraded before High Heaven in the guise of Reform, the most childish has been the idea that the editor could vindicate his independence only by sitting on the fence and throwing stones with impartial vigor alike at friend and foe.

Newspapers expand west

As

the country and its inhabitants explored and settled further west the

American landscape changed. In order to supply these new pioneers of

western territories with information, publishing was forced to expand

past the major presses of Washington D.C. and New York. Most frontier

newspapers were creations of the influx of people and wherever a new

town sprang up a newspaper was sure to follow.

However other times a printer was hired by a town settler to move to

the location and set up a newspaper in order to legitimize the town and

draw other settlers. Many of the newspapers and journals published in

these Midwestern developments were weekly papers. Homesteaders would

watch their cattle or farms during the week and then on their weekend

journey readers would collect their papers while they did their business

in town. One reason that so many newspapers were started during the

conquest of the West was that homesteaders were required to publish

notices of their land claims in local newspapers. Some of these papers

died out after the land rushes ended, or when the railroad bypassed the town.

The rise of the wire services

The American Civil War

had a profound effect on American journalism. Large newspapers hired

war correspondents to cover the battlefields, with more freedom than

correspondents today enjoy. These reporters used the new telegraph and

expanding railways to move news reports faster to their newspapers. The

cost of sending telegraphs helped create a new concise or "tight" style

of writing which became the standard for journalism through the next

century.

The ever-growing demand for urban newspapers to provide more news

led to the organization of the first of the wire services, a

cooperative between six large New York City-based newspapers led by David Hale, the publisher of the Journal of Commerce, and James Gordon Bennett, to provide coverage of Europe for all of the papers together. What became the Associated Press received the first cable transmission ever of European news through the trans-Atlantic cable in 1858.

New forms of journalism

The New York dailies continued to redefine journalism. James Bennett's Herald, for example, didn't just write about the disappearance of David Livingstone in Africa; they sent Henry Stanley to find him, which he did, in Uganda.

The success of Stanley's stories prompted Bennett to hire more of what

would turn out to be investigative journalists. He also was the first

American publisher to bring an American newspaper to Europe by founding

the Paris Herald, which was the precursor of the International Herald Tribune. Charles Anderson Dana of the New York Sun developed the idea of the human interest story and a better definition of news value, including uniqueness of a story.

Yellow journalism

William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer both owned newspapers in the American West, and both established papers in New York City: Hearst's New York Journal in 1883 and Pulitzer's New York World

in 1896. Their stated mission to defend the public interest, their

circulation wars and sensational reporting spread to many other

newspapers and became known as "yellow journalism." The public may have initially benefited as "muckraking" journalism

exposed corruption, but its often excessively sensational coverage of a

few juicy stories alienated many readers.

Headlines

More

generally, newspapers in large cities in the 1890s began using

large-font multi-column headlines to attract passers-by to buy the

paper. Previously headlines had seldom been more than one column wide,

although multicolumn-width headlines were possible on the presses then

in use. The change required typesetters to break with tradition and many

small-town papers were reluctant to change.

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era saw a strong middle class demand for reform, which the leading newspapers and magazines supported with editorial crusades.

Building on President McKinley's effective use of the press, President Theodore Roosevelt made his White House

the center of news every day, providing interviews and photo

opportunities. After noticing the White House reporters huddled outside

in the rain one day, he gave them their own room inside, effectively

inventing the presidential press briefing. The grateful press, with

unprecedented access to the White House, rewarded Roosevelt with intense

favorable coverage; The nation's editorial cartoonists loved him even

more. Roosevelt's main goal was to promote discussion and support for his package of Square Deal reform policies among his base in the middle-class. When the media strayed too far from his list of approved targets, he criticized them as mud flinging muckrakers.

Journalism historians pay by far the most attention to the big

city newspapers, largely ignoring small-town dailies and weeklies that

proliferated and dealt heavily in local news. Rural America was also

served by specialized farm magazines. By 1910 most farmers subscribed to

one. Their editors typically promoted efficiency in farming, With

reports of new machinery, new seats, new techniques, and county and

state fairs.

Muckraking

Muckrakers were investigative journalists, sponsored by large

national magazines, who investigated political corruption, as well as

misdeeds by corporations and labor unions.

Exposés attracted a middle-class upscale audience during the Progressive Era, especially in 1902 – 1912. By the 1900s, such major magazines as Collier's Weekly, Munsey's Magazine and McClure's Magazine were sponsoring exposés for a national audience. The January 1903 issue of McClure's marked the beginning of muckraking journalism, while the muckrakers would get their label later. Ida M. Tarbell ("The History of Standard Oil"), Lincoln Steffens ("The Shame of Minneapolis") and Ray Stannard Baker

("The Right to Work"), simultaneously published famous works in that

single issue. Claude H. Wetmore and Lincoln Steffens' previous article

"Tweed Days in St. Louis", in McClure's October 1902 issue was the first muckraking article.

President Roosevelt enjoyed very close relationships with the

press, which he used to keep in daily contact with his middle-class

base. Before taking office, he had made a living as a writer and

magazine editor. He loved talking with intellectuals, authors and

writers. He drew the line, however, at expose-oriented scandal-mongering

journalists who during his term set magazine subscriptions soaring with

attacks on corrupt politicians, mayors, and corporations. Roosevelt

himself was not a target, but his speech in 1906 coined the term "muckraker"

for unscrupulous journalists making wild charges. "The liar," he said,

"is no whit better than the thief, and if his mendacity takes the form

of slander he may be worse than most thieves."

The muckraking style fell out of fashion after 1917, as the media

pulled together to support the war effort with minimum criticism of

personalities.

In the 1960s, investigative journalism came back into play with the 'Washington Post

exposés of the Watergate scandal. At the local level, the alternative

press movement emerged, typified by alternative weekly newspapers like The Village Voice in New York City and The Phoenix in Boston, as well as political magazines like Mother Jones and The Nation.

Professionalization

Winfield

argues that 1908 represented a turning point in the professionalization

of journalism, as characterized by the new journalism schools, the

founding of the National Press Club, and such technological innovations as newsreels, the use of halftones to print photographs, and changes in newspaper design.

Reporters wrote the stories that sold papers, but shared only a

fraction of the income. The highest salaries went to New York reporters,

topping out at $40 to $60 a week. Pay scales were lower in smaller

cities, only $5 to $20 a week at smaller dailies. The quality of

reporting increased sharply, and its reliability improved; drunkenness

became less and less of a problem. Pulitzer gave Columbia University $2 million in 1912 to create a school of journalism that has retained leadership status into the 21st century. Other notable schools were founded at the University of Missouri and the Medill School Northwestern University.

Freedom of the press became well-established legal principle, although President Theodore Roosevelt

tried to sue major papers for reporting corruption in the purchase of

the Panama Canal rights. The federal court threw out the lawsuit, ending

the only attempt by the federal government to sue newspapers for libel

since the days of the Sedition Act

of 1798. Roosevelt had a more positive impact on journalism -- he

provided a steady stream of lively copy, making the White House the

center of national reporting.

Rise of the African-American press

Rampant discrimination against African-Americans did not prevent them

from founding their own daily and weekly newspapers, especially in

large cities, and these flourished because of the loyalty of their

readers. The first black newspaper was the Freedom's Journal, first published on March 16, 1827 by John B. Russwurm and Samuel Cornish. Abolitionist Philip Alexander Bell (1808-1886) started the Colored American in New York City in 1837, then became co-editor of The Pacific Appeal and founder of The Elevator, both significant Reconstruction Era newspapers based in San Francisco.

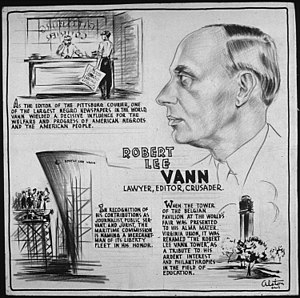

Poster from the U.S. Office of War Information, 1943

By the 20th century, African-American newspapers flourished in the

major cities, with their publishers playing a major role in politics and

business affairs, including

- Robert Sengstacke Abbott ( 1870-1940), publisher of the Chicago Defender;

- John Mitchell, Jr. (1863 – 1929), editor of the Richmond Planet and president of the National Afro-American Press Association;

- Anthony Overton (1865 – 1946), publisher of the Chicago Bee, and

- Robert Lee Vann (1879 – 1940), the publisher and editor of the Pittsburgh Courier.

Foreign-language newspapers

As

immigration rose dramatically during the last half of the 19th century,

many ethnic groups sponsored newspapers in their native languages to

cater to their fellow expatriates. The Germans created the largest

network, but their press was largely shut down in 1917-1918. Yiddish

Newspapers appeared for New York Jews. They had the effect of

introducing newcomers from Eastern Europe to American culture and

society.

In states like Nebraska, founded on large immigrants populations,

where many residents moved from Czechoslovakia, Germany and Denmark

foreign-language papers provided a place for these people to make

cultural and economic contributions to their new country and home.

Today, Spanish language newspapers such as El Diario La Prensa (founded in 1913) exist in Hispanic strongholds, but their circulations are small.

Between the wars

Broadcast

journalism began slowly in the 1920s, at a time when stations broadcast

music and occasional speeches, and expanded slowly in the 1930s as

radio moved to drama and entertainment. Radio exploded in importance

during World War II, but after 1950 was overtaken by television news.

The newsreel developed in the 1920s and flourished before the daily

television news broadcasts in the 1950s doomed its usefulness.

Luce empire

The first issue of Time (March 3, 1923), featuring House Speaker Joseph G. Cannon.

News magazines flourished from the late 19th century on, such as Outlook and Review of Reviews. However, in 1923 Henry Luce (1898-1967) transformed the genre with Time,

which became a favorite news source for the upscale middle-class. Luce,

a conservative Republican, was called "the most influential private

citizen in the America of his day."

He launched and closely supervised a stable of magazines that

transformed journalism and the reading habits of upscale Americans. Time summarized and interpreted the week's news. Life

was a picture magazine of politics, culture and society that dominated

American visual perceptions in the era before television. Fortune explored in depth the economy and the world of business, introducing to executives avant-garde ideas such as Keynesianism. Sports Illustrated probed beneath the surface of the game to explore the motivations and strategies of the teams and key players. Add in his radio projects and newsreels,

and Luce created a multimedia corporation to rival that of Hearst and

other newspaper chains. Luce, born in China to missionary parents,

demonstrated a missionary zeal to make the nation worthy of dominating

the world in what he called the "American Century." Luce hired

outstanding journalists—some of them serious intellectuals, as well as talented editors. By the late 20th century, however, all the Luce magazines and their imitators (such as Newsweek and Look) had drastically scaled back. Newsweek ended its print edition in 2013.

21st century Internet

Following the emergence of browsers, USA Today

became the first newspaper to offer an online version of its

publication in 1995, though CNN launched its own site later that year.

However, especially after 2000, the Internet brought "free" news and

classified advertising to audiences that no longer saw a reason for

subscriptions, undercutting the business model of many daily newspapers.

Bankruptcy loomed across the U.S. and did hit such major papers as the Rocky Mountain News (Denver), the Chicago Tribune and the Los Angeles Times, among many others. Chapman and Nuttall

find that proposed solutions, such as multiplatforms, paywalls,

PR-dominated news gathering, and shrinking staffs have not resolved the

challenge. The result, they argue, is that journalism today is

characterized by four themes: personalization, globalization,

localization, and

pauperization.

Nip presents a typology of five models of audience connections:

traditional journalism, public journalism, interactive journalism,

participatory journalism, and citizen journalism. He identifies the

higher goal of public journalism as engaging the people as citizens and

helping public deliberation.

Investigative journalism declined at major daily newspapers in

the 2000s, and many reporters formed their own non-profit investigative

newsrooms, for example ProPublica on the national level, Texas Tribune at the state level and Voice of OC at the local level.

A 2014 study by the University of Indiana under The American Journalist

header, a series of studies that go back to the 1970s, found that of

the journalists they surveyed, significantly more identified as

Democrats than Republicans (28% verse 7%). This coincided with reduced staffing at local papers and possibly their replacement by online outlets in eastern liberal cites.

Historiography

Journalism historian David Nord has argued that in the 1960s and 1970s:

- In journalism history and media history, a new generation of scholars ... criticized traditional histories of the media for being too insular, too decontextualized, too uncritical, too captive to the needs of professional training, and too enamored of the biographies of men and media organizations.

In 1974, James W. Carey identified the ‘Problem of Journalism History’. The field was

dominated by a Whig interpretation of journalism history.

- This views journalism history as the slow, steady expansion of freedom and knowledge from the political press to the commercial press, the setbacks into sensationalism and yellow journalism, the forward thrust into muck raking and social responsibility....the entire story is framed by those large impersonal forces buffeting the press: industrialization, urbanization and mass democracy.

O'Malley says the criticism went too far, because there was much of value in the deep scholarship of the earlier period.