In English, the term is chiefly used in the US. In the UK, a roughly equivalent term is tabloid journalism, meaning journalism characteristic of tabloid newspapers, even if found elsewhere. Other languages, e.g. Russian (Жёлтая пресса), sometimes have terms derived from the American term. A common source of such writing is called checkbook journalism,

which is the controversial practice of news reporters paying sources

for their information without verifying its truth or accuracy. In the

U.S. it is generally considered unethical, with most mainstream

newspapers and news shows having a policy forbidding it. In contrast,

tabloid newspapers and tabloid television shows, which rely more on

sensationalism, regularly engage in the practice.

Frank Luther Mott identifies yellow journalism based on five characteristics:

The term was coined by Erwin Wardman, the editor of the New York Press. Wardman was the first to publish the term but there is evidence that expressions such as "yellow journalism" and "school of yellow kid journalism" were already used by newsmen of that time. Wardman never defined the term exactly. Possibly it was a mutation from earlier slander where Wardman twisted "new journalism" into "nude journalism". Wardman had also used the expression "yellow kid journalism" referring to the then-popular comic strip which was published by both Pulitzer and Hearst during a circulation war. In 1898 the paper simply elaborated: "We called them Yellow because they are Yellow."

Definitions

Joseph Campbell describes yellow press newspapers as having daily multi-column front-page headlines covering a variety of topics, such as sports and scandal, using bold layouts (with large illustrations and perhaps color), heavy reliance on unnamed sources, and unabashed self-promotion. The term was extensively used to describe certain major New York City newspapers around 1900 as they battled for circulation.Frank Luther Mott identifies yellow journalism based on five characteristics:

- scare headlines in huge print, often of minor news

- lavish use of pictures, or imaginary drawings

- use of faked interviews, misleading headlines, pseudoscience, and a parade of false learning from so-called experts

- emphasis on full-color Sunday supplements, usually with comic strips

- dramatic sympathy with the "underdog" against the system.

Origins: Pulitzer vs. Hearst

Etymology and early usage

The term was coined in the mid-1890s to characterize the sensational journalism that used some yellow ink in the circulation war between Joseph Pulitzer's New York World and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal. The battle peaked from 1895 to about 1898, and historical usage often refers specifically to this period. Both papers were accused by critics of sensationalizing the news in order to drive up circulation, although the newspapers did serious reporting as well. An English magazine in 1898 noted, "All American journalism is not 'yellow', though all strictly 'up-to-date' yellow journalism is American!"The term was coined by Erwin Wardman, the editor of the New York Press. Wardman was the first to publish the term but there is evidence that expressions such as "yellow journalism" and "school of yellow kid journalism" were already used by newsmen of that time. Wardman never defined the term exactly. Possibly it was a mutation from earlier slander where Wardman twisted "new journalism" into "nude journalism". Wardman had also used the expression "yellow kid journalism" referring to the then-popular comic strip which was published by both Pulitzer and Hearst during a circulation war. In 1898 the paper simply elaborated: "We called them Yellow because they are Yellow."

Hearst in San Francisco, Pulitzer in New York

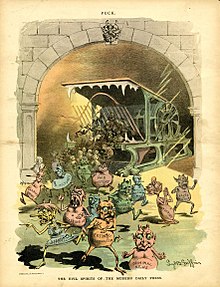

"Evil spirits", such as "Paid Puffery" and "Suggestiveness", spew from "the modern daily press" in this Puck cartoon of November 21, 1888

Joseph Pulitzer purchased the New York World in 1883 after making the St. Louis Post-Dispatch the dominant daily in that city. Pulitzer strove to make the New York World

an entertaining read, and filled his paper with pictures, games and

contests that drew in new readers. Crime stories filled many of the

pages, with headlines like "Was He a Suicide?" and "Screaming for

Mercy."

In addition, Pulitzer only charged readers two cents per issue but gave

readers eight and sometimes 12 pages of information (the only other two

cent paper in the city never exceeded four pages).

While there were many sensational stories in the New York World,

they were by no means the only pieces, or even the dominant ones.

Pulitzer believed that newspapers were public institutions with a duty

to improve society, and he put the World in the service of social reform.

Just two years after Pulitzer took it over, the World became the highest circulation newspaper in New York, aided in part by its strong ties to the Democratic Party. Older publishers, envious of Pulitzer's success, began criticizing the World,

harping on its crime stories and stunts while ignoring its more serious

reporting — trends which influenced the popular perception of yellow

journalism. Charles Dana, editor of the New York Sun, attacked The World and said Pulitzer was "deficient in judgment and in staying power."

Pulitzer's approach made an impression on William Randolph Hearst, a mining heir who acquired the San Francisco Examiner from his father in 1887. Hearst read the World while studying at Harvard University and resolved to make the Examiner as bright as Pulitzer's paper.

Under his leadership, the Examiner devoted 24 percent of its space to crime, presenting the stories as morality plays, and sprinkled adultery and "nudity" (by 19th century standards) on the front page. A month after Hearst took over the paper, the Examiner ran this headline about a hotel fire: HUNGRY, FRANTIC FLAMES. They Leap Madly Upon the Splendid Pleasure Palace by the Bay of Monterey, Encircling Del Monte in Their Ravenous Embrace From Pinnacle to Foundation. Leaping Higher, Higher, Higher, With Desperate Desire. Running Madly Riotous Through Cornice, Archway and Facade. Rushing in Upon the Trembling Guests with Savage Fury. Appalled and Panic-Striken the Breathless Fugitives Gaze Upon the Scene of Terror. The Magnificent Hotel and Its Rich Adornments Now a Smoldering heap of Ashes. The Examiner Sends a Special Train to Monterey to Gather Full Details of the Terrible Disaster. Arrival of the Unfortunate Victims on the Morning's Train — A History of Hotel del Monte — The Plans for Rebuilding the Celebrated Hostelry — Particulars and Supposed Origin of the Fire.

Hearst could be hyperbolic in his crime coverage; one of his early pieces, regarding a "band of murderers," attacked the police for forcing Examiner reporters to do their work for them. But while indulging in these stunts, the Examiner also increased its space for international news, and sent reporters out to uncover municipal corruption and inefficiency.

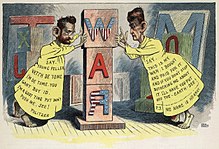

"The Yellow Press", by L. M. Glackens, portrays William Randolph Hearst as a jester distributing sensational stories

In one well remembered story, Examiner reporter Winifred Black was admitted into a San Francisco hospital and discovered that indigent women were treated with "gross cruelty." The entire hospital staff was fired the morning the piece appeared.

Competition in New York

"Yellow journalism" cartoon about Spanish–American War of 1898. The newspaper publishers Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst are both attired as the Yellow Kid comics character of the time, and are competitively claiming ownership of the war.

With the success of the Examiner established by the early 1890s, Hearst began looking for a New York newspaper to purchase, and acquired the New York Journal in 1895, a penny paper which Pulitzer's brother Albert had sold to a Cincinnati publisher the year before.

Metropolitan newspapers

started going after department store advertising in the 1890s, and

discovered the larger the circulation base, the better. This drove

Hearst; following Pulitzer's earlier strategy, he kept the Journal's price at one cent (compared to The World's two cent price) while providing as much information as rival newspapers. The approach worked, and as the Journal's

circulation jumped to 150,000, Pulitzer cut his price to a penny,

hoping to drive his young competitor (who was subsidized by his family's

fortune) into bankruptcy.

In a counterattack, Hearst raided the staff of the World

in 1896. While most sources say that Hearst simply offered more money,

Pulitzer — who had grown increasingly abusive to his employees — had

become an extremely difficult man to work for, and many World employees were willing to jump for the sake of getting away from him.

Although the competition between the World and the Journal

was fierce, the papers were temperamentally alike. Both were

Democratic, both were sympathetic to labor and immigrants (a sharp

contrast to publishers like the New York Tribune's Whitelaw Reid, who blamed their poverty on moral defects),

and both invested enormous resources in their Sunday publications,

which functioned like weekly magazines, going beyond the normal scope of

daily journalism.

Their Sunday entertainment features included the first color comic strip pages, and some theorize that the term yellow journalism originated there, while as noted above, the New York Press left the term it invented undefined. Hogan's Alley, a comic strip revolving around a bald child in a yellow nightshirt (nicknamed The Yellow Kid), became exceptionally popular when cartoonist Richard F. Outcault began drawing it in the World in early 1896. When Hearst predictably hired Outcault away, Pulitzer asked artist George Luks to continue the strip with his characters, giving the city two Yellow Kids.

The use of "yellow journalism" as a synonym for over-the-top

sensationalism in the U.S. apparently started with more serious

newspapers commenting on the excesses of "the Yellow Kid papers."

In 1890, Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis published "The Right to Privacy",

considered the most influential of all law review articles, as a

critical response to sensational forms of journalism, which they saw as

an unprecedented threat to individual privacy. The article is widely

considered to have led to the recognition of new common law privacy

rights of action.

Spanish–American War

Male Spanish officials strip search an American woman tourist in Cuba looking for messages from rebels; front page "yellow journalism" from Hearst (Artist: Frederic Remington)

Pulitzer's treatment in the World emphasizes a horrible explosion

Hearst's treatment was more effective and focused on the enemy who set the bomb—and offered a huge reward to readers

Pulitzer and Hearst are often adduced as the cause of the United States' entry into the Spanish–American War due to sensationalist stories or exaggerations of the terrible conditions in Cuba.

However, the vast majority of Americans did not live in New York City,

and the decision-makers who did live there probably relied more on staid

newspapers like the Times, The Sun, or the Post. James Creelman wrote an anecdote in his memoir that artist Frederic Remington

telegrammed Hearst to tell him all was quiet in Cuba and "There will be

no war." Creelman claimed Hearst responded "Please remain. You

furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war." Hearst denied the

veracity of the story, and no one has found any evidence of the

telegrams existing. Historian Emily Erickson states:

Serious historians have dismissed the telegram story as unlikely. ... The hubris contained in this supposed telegram, however, does reflect the spirit of unabashed self-promotion that was a hallmark of the yellow press and of Hearst in particular.

Hearst became a war hawk

after a rebellion broke out in Cuba in 1895. Stories of Cuban virtue

and Spanish brutality soon dominated his front page. While the accounts

were of dubious accuracy, the newspaper readers of the 19th century did

not expect, or necessarily want, his stories to be pure nonfiction.

Historian Michael Robertson has said that "Newspaper reporters and

readers of the 1890s were much less concerned with distinguishing among

fact-based reporting, opinion and literature."

Pulitzer, though lacking Hearst's resources, kept the story on

his front page. The yellow press covered the revolution extensively and

often inaccurately, but conditions on Cuba were horrific enough. The

island was in a terrible economic depression, and Spanish general Valeriano Weyler, sent to crush the rebellion, herded Cuban peasants into concentration camps,

leading hundreds of Cubans to their deaths. Having clamored for a fight

for two years, Hearst took credit for the conflict when it came: A week

after the United States declared war on Spain, he ran "How do you like

the Journal's war?" on his front page. In fact, President William McKinley never read the Journal, nor newspapers like the Tribune and the New York Evening Post.

Moreover, journalism historians have noted that yellow journalism was

largely confined to New York City, and that newspapers in the rest of

the country did not follow their lead. The Journal and the World

were not among the top ten sources of news in regional papers, and the

stories simply did not make a splash outside New York City.

Rather, war came because public opinion was sickened by the bloodshed,

and because leaders like McKinley realized that Spain had lost control

of Cuba. These factors weighed more on the president's mind than the melodramas in the New York Journal.

When the invasion began, Hearst sailed directly to Cuba as a war

correspondent, providing sober and accurate accounts of the fighting.

Creelman later praised the work of the reporters for exposing the

horrors of Spanish misrule, arguing, "no true history of the war ... can

be written without an acknowledgment that whatever of justice and

freedom and progress was accomplished by the Spanish–American War was

due to the enterprise and tenacity of yellow journalists, many of whom lie in unremembered graves."

After the war

Hearst was a leading Democrat who promoted William Jennings Bryan

for president in 1896 and 1900. He later ran for mayor and governor and

even sought the presidential nomination, but lost much of his personal

prestige when outrage exploded in 1901 after columnist Ambrose Bierce and editor Arthur Brisbane published separate columns months apart that suggested the assassination of William McKinley. When McKinley was shot on September 6, 1901, critics accused Hearst's Yellow Journalism of driving Leon Czolgosz

to the deed. Hearst did not know of Bierce's column, and claimed to

have pulled Brisbane's after it ran in a first edition, but the incident

would haunt him for the rest of his life, and all but destroyed his

presidential ambitions.

Pulitzer, haunted by his "yellow sins," returned the World to its crusading roots as the new century dawned. By the time of his death in 1911, the World

was a widely respected publication, and would remain a leading

progressive paper until its demise in 1931. Its name lived on in the Scripps-Howard New York World-Telegram, and then later the New York World-Telegram and Sun in 1950, and finally was last used by the New York World-Journal-Tribune from September 1966 to May 1967. At that point, only one broadsheet newspaper was left in New York City.