Assuming that the standard model of cosmology is correct, the best current measurements indicate that dark energy contributes 68% of the total energy in the present-day observable universe. The mass–energy of dark matter and ordinary (baryonic) matter contribute 27% and 5%, respectively, and other components such as neutrinos and photons contribute a very small amount. The density of dark energy is very low (~ 7 × 10−30 g/cm3)

much less than the density of ordinary matter or dark matter within

galaxies. However, it dominates the mass–energy of the universe because

it is uniform across space.

Two proposed forms for dark energy are the cosmological constant, representing a constant energy density filling space homogeneously, and scalar fields such as quintessence or moduli, dynamic quantities whose energy density can vary in time and space. Contributions from scalar fields that are constant in space are usually also included in the cosmological constant. The cosmological constant can be formulated to be equivalent to the zero-point radiation of space i.e. the vacuum energy. Scalar fields that change in space can be difficult to distinguish from a cosmological constant because the change may be extremely slow.

Two proposed forms for dark energy are the cosmological constant, representing a constant energy density filling space homogeneously, and scalar fields such as quintessence or moduli, dynamic quantities whose energy density can vary in time and space. Contributions from scalar fields that are constant in space are usually also included in the cosmological constant. The cosmological constant can be formulated to be equivalent to the zero-point radiation of space i.e. the vacuum energy. Scalar fields that change in space can be difficult to distinguish from a cosmological constant because the change may be extremely slow.

History of discovery and previous speculation

Einstein's cosmological constant

The "cosmological constant" is a constant term that can be added to Einstein's field equation

of general relativity. If considered as a "source term" in the field

equation, it can be viewed as equivalent to the mass of empty space

(which conceptually could be either positive or negative), or "vacuum energy".

The cosmological constant was first proposed by Einstein as a mechanism to obtain a solution of the gravitational field equation that would lead to a static universe, effectively using dark energy to balance gravity.

Einstein gave the cosmological constant the symbol Λ (capital lambda).

Einstein stated that the cosmological constant required that `empty

space takes the role of gravitating negative masses which are distributed all over the interstellar space'.

The mechanism was an example of fine-tuning,

and it was later realized that Einstein's static universe would not be

stable: local inhomogeneities would ultimately lead to either the

runaway expansion or contraction of the universe. The equilibrium

is unstable: if the universe expands slightly, then the expansion

releases vacuum energy, which causes yet more expansion. Likewise, a

universe which contracts slightly will continue contracting. These sorts

of disturbances are inevitable, due to the uneven distribution of

matter throughout the universe. Further, observations made by Edwin Hubble

in 1929 showed that the universe appears to be expanding and not static

at all. Einstein reportedly referred to his failure to predict the idea

of a dynamic universe, in contrast to a static universe, as his

greatest blunder.

Inflationary dark energy

Alan Guth and Alexei Starobinsky proposed in 1980 that a negative pressure field, similar in concept to dark energy, could drive cosmic inflation

in the very early universe. Inflation postulates that some repulsive

force, qualitatively similar to dark energy, resulted in an enormous and

exponential expansion of the universe slightly after the Big Bang.

Such expansion is an essential feature of most current models of the

Big Bang. However, inflation must have occurred at a much higher energy

density than the dark energy we observe today and is thought to have

completely ended when the universe was just a fraction of a second old.

It is unclear what relation, if any, exists between dark energy and

inflation. Even after inflationary models became accepted, the

cosmological constant was thought to be irrelevant to the current

universe.

Nearly all inflation models predict that the total (matter+energy) density of the universe should be very close to the critical density. During the 1980s, most cosmological research focused on models with critical density in matter only, usually 95% cold dark matter

and 5% ordinary matter (baryons). These models were found to be

successful at forming realistic galaxies and clusters, but some problems

appeared in the late 1980s: in particular, the model required a value

for the Hubble constant

lower than preferred by observations, and the model under-predicted

observations of large-scale galaxy clustering. These difficulties became

stronger after the discovery of anisotropy in the cosmic microwave background by the COBE spacecraft in 1992, and several modified CDM models came under active study through the mid-1990s: these included the Lambda-CDM model and a mixed cold/hot dark matter model. The first direct evidence for dark energy came from supernova observations in 1998 of accelerated expansion in Riess et al. and in Perlmutter et al.,

and the Lambda-CDM model then became the leading model. Soon after,

dark energy was supported by independent observations: in 2000, the BOOMERanG and Maxima cosmic microwave background experiments observed the first acoustic peak in the CMB, showing that the total (matter+energy) density is close to 100% of critical density. Then in 2001, the 2dF Galaxy Redshift Survey

gave strong evidence that the matter density is around 30% of critical.

The large difference between these two supports a smooth component of

dark energy making up the difference. Much more precise measurements

from WMAP in 2003–2010 have continued to support the standard model and give more accurate measurements of the key parameters.

The term "dark energy", echoing Fritz Zwicky's "dark matter" from the 1930s, was coined by Michael Turner in 1998.

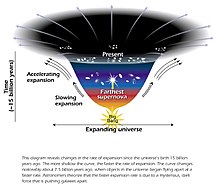

Change in expansion over time

Diagram representing the accelerated expansion of the universe due to dark energy.

High-precision measurements of the expansion of the universe are required to understand how the expansion rate changes over time and space. In general relativity, the evolution of the expansion rate is estimated from the curvature of the universe and the cosmological equation of state

(the relationship between temperature, pressure, and combined matter,

energy, and vacuum energy density for any region of space). Measuring

the equation of state for dark energy is one of the biggest efforts in

observational cosmology today. Adding the cosmological constant to

cosmology's standard FLRW metric leads to the Lambda-CDM model, which has been referred to as the "standard model of cosmology" because of its precise agreement with observations.

As of 2013, the Lambda-CDM model is consistent with a series of increasingly rigorous cosmological observations, including the Planck spacecraft

and the Supernova Legacy Survey. First results from the SNLS reveal

that the average behavior (i.e., equation of state) of dark energy

behaves like Einstein's cosmological constant to a precision of 10%.

Recent results from the Hubble Space Telescope Higher-Z Team indicate

that dark energy has been present for at least 9 billion years and

during the period preceding cosmic acceleration.

Nature

The nature of dark energy is more hypothetical than that of dark matter, and many things about it remain matters of speculation. Dark energy is thought to be very homogeneous and not very dense, and is not known to interact through any of the fundamental forces other than gravity. Since it is quite rarefied and un-massive — roughly 10−27 kg/m3

— it is unlikely to be detectable in laboratory experiments. The reason

dark energy can have such a profound effect on the universe, making up

68% of universal density in spite of being so dilute, is that it

uniformly fills otherwise empty space.

Independently of its actual nature, dark energy would need to have a strong negative pressure (repulsive action), like radiation pressure in a metamaterial, to explain the observed acceleration of the expansion of the universe.

According to general relativity, the pressure within a substance

contributes to its gravitational attraction for other objects just as

its mass density does. This happens because the physical quantity that

causes matter to generate gravitational effects is the stress–energy tensor, which contains both the energy (or matter) density of a substance and its pressure and viscosity. In the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric,

it can be shown that a strong constant negative pressure in all the

universe causes an acceleration in the expansion if the universe is

already expanding, or a deceleration in contraction if the universe is

already contracting. This accelerating expansion effect is sometimes

labeled "gravitational repulsion".

Technical definition

In standard cosmology, there are three components of the universe:

matter, radiation, and dark energy. Matter is anything whose energy

density scales with the inverse cube of the scale factor, i.e., ρ ∝ a−3, while radiation is anything which scales to the inverse fourth power of the scale factor (ρ ∝ a−4).

This can be understood intuitively: for an ordinary particle in a

square box, doubling the length of a side of the box decreases the

density (and hence energy density) by a factor of eight (23). For radiation, the decrease in energy density is greater, because an increase in spatial distance also causes a redshift.

The final component, dark energy, is an intrinsic property of

space, and so has a constant energy density regardless of the volume

under consideration (ρ ∝ a0). Thus, unlike ordinary matter, it does not get diluted with the expansion of space.

Evidence of existence

The evidence for dark energy is indirect but comes from three independent sources:

- Distance measurements and their relation to redshift, which suggest the universe has expanded more in the last half of its life.

- The theoretical need for a type of additional energy that is not matter or dark matter to form the observationally flat universe (absence of any detectable global curvature).

- Measures of large-scale wave-patterns of mass density in the universe.

Supernovae

A Type Ia supernova (bright spot on the bottom-left) near a galaxy

In 1998, the High-Z Supernova Search Team published observations of Type Ia ("one-A") supernovae. In 1999, the Supernova Cosmology Project followed by suggesting that the expansion of the universe is accelerating. The 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Saul Perlmutter, Brian P. Schmidt, and Adam G. Riess for their leadership in the discovery.

Since then, these observations have been corroborated by several independent sources. Measurements of the cosmic microwave background, gravitational lensing, and the large-scale structure of the cosmos, as well as improved measurements of supernovae, have been consistent with the Lambda-CDM model.

Some people argue that the only indications for the existence of dark

energy are observations of distance measurements and their associated

redshifts. Cosmic microwave background anisotropies and baryon acoustic

oscillations serve only to demonstrate that distances to a given

redshift are larger than would be expected from a "dusty"

Friedmann–Lemaître universe and the local measured Hubble constant.

Supernovae are useful for cosmology because they are excellent standard candles

across cosmological distances. They allow researchers to measure the

expansion history of the universe by looking at the relationship between

the distance to an object and its redshift, which gives how fast it is receding from us. The relationship is roughly linear, according to Hubble's law.

It is relatively easy to measure redshift, but finding the distance to

an object is more difficult. Usually, astronomers use standard candles:

objects for which the intrinsic brightness, or absolute magnitude, is known. This allows the object's distance to be measured from its actual observed brightness, or apparent magnitude. Type Ia supernovae are the best-known standard candles across cosmological distances because of their extreme and consistent luminosity.

Recent observations of supernovae are consistent with a universe made up 71.3% of dark energy and 27.4% of a combination of dark matter and baryonic matter.

Cosmic microwave background

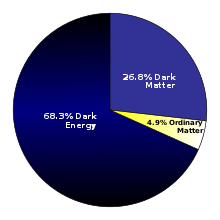

Estimated division of total energy in the universe into matter, dark matter and dark energy based on five years of WMAP data.

The existence of dark energy, in whatever form, is needed to

reconcile the measured geometry of space with the total amount of matter

in the universe. Measurements of cosmic microwave background (CMB) anisotropies indicate that the universe is close to flat. For the shape of the universe to be flat, the mass-energy density of the universe must be equal to the critical density. The total amount of matter in the universe (including baryons and dark matter),

as measured from the CMB spectrum, accounts for only about 30% of the

critical density. This implies the existence of an additional form of

energy to account for the remaining 70%. The Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) spacecraft seven-year analysis estimated a universe made up of 72.8% dark energy, 22.7% dark matter, and 4.5% ordinary matter.

Work done in 2013 based on the Planck spacecraft observations of the CMB gave a more accurate estimate of 68.3% dark energy, 26.8% dark matter, and 4.9% ordinary matter.

Large-scale structure

The theory of large-scale structure, which governs the formation of structures in the universe (stars, quasars, galaxies and galaxy groups and clusters), also suggests that the density of matter in the universe is only 30% of the critical density.

A 2011 survey, the WiggleZ galaxy survey of more than 200,000

galaxies, provided further evidence towards the existence of dark

energy, although the exact physics behind it remains unknown. The WiggleZ survey from the Australian Astronomical Observatory scanned the galaxies to determine their redshift. Then, by exploiting the fact that baryon acoustic oscillations have left voids

regularly of ~150 Mpc diameter, surrounded by the galaxies, the voids

were used as standard rulers to estimate distances to galaxies as far as

2,000 Mpc (redshift 0.6), allowing for accurate estimate of the speeds

of galaxies from their redshift and distance. The data confirmed cosmic acceleration up to half of the age of the universe (7 billion years) and constrain its inhomogeneity to 1 part in 10. This provides a confirmation to cosmic acceleration independent of supernovae.

Late-time integrated Sachs-Wolfe effect

Accelerated cosmic expansion causes gravitational potential wells and hills to flatten as photons

pass through them, producing cold spots and hot spots on the CMB

aligned with vast supervoids and superclusters. This so-called late-time

Integrated Sachs–Wolfe effect (ISW) is a direct signal of dark energy in a flat universe. It was reported at high significance in 2008 by Ho et al. and Giannantonio et al.

Observational Hubble constant data

A new approach to test evidence of dark energy through observational Hubble constant data (OHD) has gained significant attention in recent years. The Hubble constant, H(z), is measured as a function of cosmological redshift.

OHD directly tracks the expansion history of the universe by taking

passively evolving early-type galaxies as “cosmic chronometers”.

From this point, this approach provides standard clocks in the

universe. The core of this idea is the measurement of the differential

age evolution as a function of redshift of these cosmic chronometers.

Thus, it provides a direct estimate of the Hubble parameter

The reliance on a differential quantity, Δz/Δt,

can minimize many common issues and systematic effects; and as a direct

measurement of the Hubble parameter instead of its integral, like supernovae and baryon acoustic oscillations

(BAO), it brings more information and is appealing in computation. For

these reasons, it has been widely used to examine the accelerated cosmic

expansion and study properties of dark energy.

Theories of dark energy

Dark

energy's status as a hypothetical force with unknown properties makes

it a very active target of research. The problem is attacked from a

great variety of angles, such as modifying the prevailing theory of

gravity (general relativity), attempting to pin down the properties of

dark energy, and finding alternative ways to explain the observational

data.

The equation of state of Dark Energy for 4 common models by Redshift.

A: CPL Model,

B: Jassal Model,

C: Barboza & Alcaniz Model,

D: Wetterich Model

A: CPL Model,

B: Jassal Model,

C: Barboza & Alcaniz Model,

D: Wetterich Model

Cosmological constant

The simplest explanation for dark energy is that it is an intrinsic,

fundamental energy of space. This is the cosmological constant, usually

represented by the Greek letter Λ (Lambda, hence Lambda-CDM model). Since energy and mass are related according to the equation E = mc2, Einstein's theory of general relativity predicts that this energy will have a gravitational effect. It is sometimes called a vacuum energy because it is the energy density of empty vacuum.

The cosmological constant has negative pressure equal to its energy density and so causes the expansion of the universe to accelerate.

The reason a cosmological constant has negative pressure can be seen

from classical thermodynamics. In general, energy must be lost from

inside a container (the container must do work on its environment) in

order for the volume to increase. Specifically, a change in volume dV requires work done equal to a change of energy −P dV, where P

is the pressure. But the amount of energy in a container full of vacuum

actually increases when the volume increases, because the energy is

equal to ρV, where ρ is the energy density of the cosmological constant. Therefore, P is negative and, in fact, P = −ρ.

There are two major advantages for the cosmological constant. The

first is that it is simple. Einstein had in fact introduced this term

in his original formulation of general relativity such as to get a

static universe. Although he later discarded the term after Hubble

found that the universe is expanding, a nonzero cosmological constant

can act as dark energy, without otherwise changing the Einstein field

equations. The other advantage is that there is a natural explanation

for its origin. Most quantum field theories predict vacuum fluctuations that would give the vacuum this sort of energy. This is related to the Casimir effect,

in which there is a small suction into regions where virtual particles

are geometrically inhibited from forming (e.g. between plates with tiny

separation).

A major outstanding problem is that the same quantum field theories predict a huge cosmological constant, more than 100 orders of magnitude too large. This would need to be almost, but not exactly, cancelled by an equally large term of the opposite sign. Some supersymmetric theories require a cosmological constant that is exactly zero, which does not help because supersymmetry must be broken.

Nonetheless, the cosmological constant is the most economical solution to the problem of cosmic acceleration.

Thus, the current standard model of cosmology, the Lambda-CDM model,

includes the cosmological constant as an essential feature.

Quintessence

In quintessence models of dark energy, the observed acceleration of the scale factor is caused by the potential energy of a dynamical field,

referred to as quintessence field. Quintessence differs from the

cosmological constant in that it can vary in space and time. In order

for it not to clump and form structure like matter, the field must be very light so that it has a large Compton wavelength.

No evidence of quintessence is yet available, but it has not been

ruled out either. It generally predicts a slightly slower acceleration

of the expansion of the universe than the cosmological constant. Some

scientists think that the best evidence for quintessence would come from

violations of Einstein's equivalence principle and variation of the fundamental constants in space or time. Scalar fields are predicted by the Standard Model of particle physics and string theory, but an analogous problem to the cosmological constant problem (or the problem of constructing models of cosmological inflation) occurs: renormalization theory predicts that scalar fields should acquire large masses.

The coincidence problem asks why the acceleration of the Universe began when it did. If acceleration began earlier in the universe, structures such as galaxies would never have had time to form, and life, at least as we know it, would never have had a chance to exist. Proponents of the anthropic principle

view this as support for their arguments. However, many models of

quintessence have a so-called "tracker" behavior, which solves this

problem. In these models, the quintessence field has a density which

closely tracks (but is less than) the radiation density until matter-radiation equality, which triggers quintessence to start behaving as dark energy, eventually dominating the universe. This naturally sets the low energy scale of the dark energy.

In 2004, when scientists fit the evolution of dark energy with

the cosmological data, they found that the equation of state had

possibly crossed the cosmological constant boundary (w = −1) from above

to below. A No-Go theorem has been proved that gives this scenario at

least two degrees of freedom as required for dark energy models. This

scenario is so-called Quintom scenario.

Some special cases of quintessence are phantom energy,

in which the energy density of quintessence actually increases with

time, and k-essence (short for kinetic quintessence) which has a

non-standard form of kinetic energy such as a negative kinetic energy. They can have unusual properties: phantom energy, for example, can cause a Big Rip.

Interacting dark energy

This

class of theories attempts to come up with an all-encompassing theory

of both dark matter and dark energy as a single phenomenon that modifies

the laws of gravity at various scales. This could, for example, treat

dark energy and dark matter as different facets of the same unknown

substance, or postulate that cold dark matter decays into dark energy.

Another class of theories that unifies dark matter and dark energy are

suggested to be covariant theories of modified gravity. These theories

alter the dynamics of the space-time such that the modified dynamic

stems what have been assigned to the presence of dark energy and dark

matter.

Variable dark energy models

The

density of dark energy might have varied in time over the history of

the universe. Modern observational data allow for estimates of the

present density. Using baryon acoustic oscillations, it is possible to investigate the effect of dark energy in the history of the Universe, and constrain parameters of the equation of state

of dark energy. To that end, several models have been proposed. One of

the most popular models is the Chevallier–Polarski–Linder model (CPL). Some other common models are, (Barboza & Alcaniz. 2008), (Jassal et al. 2005), (Wetterich. 2004), (Oztas et al. 2018).

Observational skepticism

Some

alternatives to dark energy aim to explain the observational data by a

more refined use of established theories. In this scenario, dark energy

doesn't actually exist, and is merely a measurement artifact. For

example, if we are located in an emptier-than-average region of space,

the observed cosmic expansion rate could be mistaken for a variation in

time, or acceleration. A different approach uses a cosmological extension of the equivalence principle

to show how space might appear to be expanding more rapidly in the

voids surrounding our local cluster. While weak, such effects considered

cumulatively over billions of years could become significant, creating

the illusion of cosmic acceleration, and making it appear as if we live

in a Hubble bubble.

Yet other possibilities are that the accelerated expansion of the

universe is an illusion caused by the relative motion of us to the rest

of the universe, or that the supernovae sample size used wasn't large enough.

Other mechanism driving acceleration

Modified gravity

The

evidence for dark energy is heavily dependent on the theory of general

relativity. Therefore, it is conceivable that a modification to general

relativity also eliminates the need for dark energy. There are very many

such theories, and research is ongoing. The measurement of the speed of gravity in the first gravitational wave measured by non-gravitational means (GW170817) ruled out many modified gravity theories as explanations to dark energy.

Astrophysicist Ethan Siegel

states that, while such alternatives gain a lot of mainstream press

coverage, almost all professional astrophysicists are confident that

dark energy exists, and that none of the competing theories successfully

explain observations to the same level of precision as standard dark

energy.

Implications for the fate of the universe

Cosmologists estimate that the acceleration began roughly 5 billion years ago.

Before that, it is thought that the expansion was decelerating, due to

the attractive influence of matter. The density of dark matter in an

expanding universe decreases more quickly than dark energy, and

eventually the dark energy dominates. Specifically, when the volume of

the universe doubles, the density of dark matter is halved, but the density of dark energy is nearly unchanged (it is exactly constant in the case of a cosmological constant).

Projections into the future can differ radically for different

models of dark energy. For a cosmological constant, or any other model

that predicts that the acceleration will continue indefinitely, the

ultimate result will be that galaxies outside the Local Group will have a line-of-sight velocity that continually increases with time, eventually far exceeding the speed of light. This is not a violation of special relativity because the notion of "velocity" used here is different from that of velocity in a local inertial frame of reference, which is still constrained to be less than the speed of light for any massive object. Because the Hubble parameter

is decreasing with time, there can actually be cases where a galaxy

that is receding from us faster than light does manage to emit a signal

which reaches us eventually.

However, because of the accelerating expansion, it is projected that

most galaxies will eventually cross a type of cosmological event horizon where any light they emit past that point will never be able to reach us at any time in the infinite future

because the light never reaches a point where its "peculiar velocity"

toward us exceeds the expansion velocity away from us. Assuming the dark energy is constant (a cosmological constant),

the current distance to this cosmological event horizon is about 16

billion light years, meaning that a signal from an event happening at present

would eventually be able to reach us in the future if the event were

less than 16 billion light years away, but the signal would never reach

us if the event were more than 16 billion light years away.

As galaxies approach the point of crossing this cosmological event horizon, the light from them will become more and more redshifted, to the point where the wavelength becomes too large to detect in practice and the galaxies appear to vanish completely. Planet Earth, the Milky Way,

and the Local Group of which the Milky way is a part, would all remain

virtually undisturbed as the rest of the universe recedes and disappears

from view. In this scenario, the Local Group would ultimately suffer heat death, just as was hypothesized for the flat, matter-dominated universe before measurements of cosmic acceleration.

There are other, more speculative ideas about the future of the universe. The phantom energy model of dark energy results in divergent

expansion, which would imply that the effective force of dark energy

continues growing until it dominates all other forces in the universe.

Under this scenario, dark energy would ultimately tear apart all

gravitationally bound structures, including galaxies and solar systems,

and eventually overcome the electrical and nuclear forces to tear apart atoms themselves, ending the universe in a "Big Rip". It is also possible the universe may never have an end and continue in its present state forever.

On the other hand, dark energy might dissipate with time or even become

attractive. Such uncertainties leave open the possibility that gravity

might yet rule the day and lead to a universe that contracts in on

itself in a "Big Crunch", or that there may even be a dark energy cycle, which implies a cyclic model of the universe in which every iteration (Big Bang then eventually a Big Crunch) takes about a trillion (1012) years. While none of these are supported by observations, they are not ruled out.

In philosophy of science

In philosophy of science, dark energy is an example of an "auxiliary hypothesis", an ad hoc postulate that is added to a theory in response to observations that falsify it. It has been argued that the dark energy hypothesis is a conventionalist hypothesis, that is, a hypothesis that adds no empirical content and hence is unfalsifiable in the sense defined by Karl Popper.