The primary evidence for dark matter is that calculations show that many galaxies

would fly apart instead of rotating, or would not have formed or move

as they do, if they did not contain a large amount of unseen matter. Other lines of evidence include observations in gravitational lensing, from the cosmic microwave background, from astronomical observations of the observable universe's current structure, from the formation and evolution of galaxies, from mass location during galactic collisions, and from the motion of galaxies within galaxy clusters. In the standard Lambda-CDM model of cosmology, the total mass–energy of the universe contains 5% ordinary matter and energy, 27% dark matter and 68% of an unknown form of energy known as dark energy. Thus, dark matter constitutes 85% of total mass, while dark energy plus dark matter constitute 95% of total mass–energy content.

Because dark matter has not yet been observed directly, it must barely interact with ordinary baryonic matter and radiation. The primary candidate for dark matter is some new kind of elementary particle that has not yet been discovered, in particular, weakly-interacting massive particles (WIMPs), or gravitationally-interacting massive particles (GIMPs). Many experiments to directly detect and study dark matter particles are being actively undertaken, but none has yet succeeded. Dark matter is classified as cold, warm, or hot according to its velocity (more precisely, its free streaming length). Current models favor a cold dark matter scenario, in which structures emerge by gradual accumulation of particles.

Although the existence of dark matter is generally accepted by the scientific community, some astrophysicists, intrigued by certain observations that do not fit the dark matter theory, argue for various modifications of the standard laws of general relativity, such as modified Newtonian dynamics, tensor–vector–scalar gravity, or entropic gravity. These models attempt to account for all observations without invoking supplemental non-baryonic matter.

Because dark matter has not yet been observed directly, it must barely interact with ordinary baryonic matter and radiation. The primary candidate for dark matter is some new kind of elementary particle that has not yet been discovered, in particular, weakly-interacting massive particles (WIMPs), or gravitationally-interacting massive particles (GIMPs). Many experiments to directly detect and study dark matter particles are being actively undertaken, but none has yet succeeded. Dark matter is classified as cold, warm, or hot according to its velocity (more precisely, its free streaming length). Current models favor a cold dark matter scenario, in which structures emerge by gradual accumulation of particles.

Although the existence of dark matter is generally accepted by the scientific community, some astrophysicists, intrigued by certain observations that do not fit the dark matter theory, argue for various modifications of the standard laws of general relativity, such as modified Newtonian dynamics, tensor–vector–scalar gravity, or entropic gravity. These models attempt to account for all observations without invoking supplemental non-baryonic matter.

History

Early history

The hypothesis of dark matter has an elaborate history. In a talk given in 1884, Lord Kelvin estimated the number of dark bodies in the Milky Way

from the observed velocity dispersion of the stars orbiting around the

center of the galaxy. By using these measurements, he estimated the mass

of the galaxy, which he determined is different from the mass of

visible stars. Lord Kelvin thus concluded that "many of our stars,

perhaps a great majority of them, may be dark bodies". In 1906 Henri Poincaré in "The Milky Way and Theory of Gases" used "dark matter", or "matière obscure" in French, in discussing Kelvin's work.

The first to suggest the existence of dark matter, using stellar velocities, was Dutch astronomer Jacobus Kapteyn in 1922. Fellow Dutchman and radio astronomy pioneer Jan Oort also hypothesized the existence of dark matter in 1932. Oort was studying stellar motions in the local galactic neighborhood

and found that the mass in the galactic plane must be greater than what

was observed, but this measurement was later determined to be

erroneous.

In 1933, Swiss astrophysicist Fritz Zwicky, who studied galaxy clusters while working at the California Institute of Technology, made a similar inference. Zwicky applied the virial theorem to the Coma Cluster and obtained evidence of unseen mass that he called dunkle Materie

('dark matter'). Zwicky estimated its mass based on the motions of

galaxies near its edge and compared that to an estimate based on its

brightness and number of galaxies. He estimated that the cluster had

about 400 times more mass than was visually observable. The gravity

effect of the visible galaxies was far too small for such fast orbits,

thus mass must be hidden from view. Based on these conclusions, Zwicky

inferred that some unseen matter provided the mass and associated

gravitation attraction to hold the cluster together. This was the first

formal inference about the existence of dark matter. Zwicky's estimates were off by more than an order of magnitude, mainly due to an obsolete value of the Hubble constant;

the same calculation today shows a smaller fraction, using greater

values for luminous mass. However, Zwicky did correctly infer that the

bulk of the matter was dark.

Further indications that the mass-to-light ratio was not unity came from measurements of galaxy rotation curves. In 1939, Horace W. Babcock reported the rotation curve for the Andromeda nebula (known now as the Andromeda Galaxy), which suggested that the mass-to-luminosity ratio increases radially.

He attributed it to either light absorption within the galaxy or

modified dynamics in the outer portions of the spiral and not to the

missing matter that he had uncovered. Following Babcock's 1939 report of unexpectedly rapid rotation in the outskirts of the Andromeda galaxy and a mass-to-light ratio of 50, in 1940 Jan Oort discovered and wrote about the large

non-visible halo of NGC 3115.

1970s

Vera Rubin, Kent Ford and Ken Freeman's in the 1960s and 1970s, provided further strong evidence, also using galaxy rotation curves. Rubin worked with a new spectrograph to measure the velocity curve of edge-on spiral galaxies with greater accuracy. This result was confirmed in 1978. An influential paper presented Rubin's results in 1980. Rubin found that most galaxies must contain about six times as much dark as visible mass; thus, by around 1980 the apparent need for dark matter was widely recognized as a major unsolved problem in astronomy.

At the same time that Rubin and Ford were exploring optical

rotation curves, radio astronomers were making use of new radio

telescopes to map the 21 cm line of atomic hydrogen in nearby galaxies.

The radial distribution of interstellar atomic hydrogen (HI)

often extends to much larger galactic radii than those accessible by

optical studies, extending the sampling of rotation curves—and thus of

the total mass distribution—to a new dynamical regime. Early mapping of

Andromeda with the 300-foot telescope at Green Bank and the 250-foot dish at Jodrell Bank

already showed that the HI rotation curve did not trace the expected

Keplerian decline. As more sensitive receivers became available, Morton

Roberts and Robert Whitehurst

were able to trace the rotational velocity of Andromeda to 30 kpc, much

beyond the optical measurements. Illustrating the advantage of tracing

the gas disk at large radii, Figure 16 of that paper combines the optical data

(the cluster of points at radii of less than 15 kpc with a single point

further out) with the HI data between 20 and 30 kpc, exhibiting the

flatness of the outer galaxy rotation curve; the solid curve peaking at

the center is the optical surface density, while the other curve shows

the cumulative mass, still rising linearly at the outermost measurement.

In parallel, the use of interferometric arrays for extragalactic HI

spectroscopy was being developed. In 1972, David Rogstad and Seth

Shostak

published HI rotation curves of five spirals mapped with the Owens

Valley interferometer; the rotation curves of all five were very flat,

suggesting very large values of mass-to-light ratio in the outer parts

of their extended HI disks.

A stream of observations in the 1980s supported the presence of dark matter, including gravitational lensing of background objects by galaxy clusters, the temperature distribution of hot gas in galaxies and clusters, and the pattern of anisotropies in the cosmic microwave background. According to consensus among cosmologists, dark matter is composed primarily of a not yet characterized type of subatomic particle. The search for this particle, by a variety of means, is one of the major efforts in particle physics.

Technical definition

In standard cosmology, matter is anything whose energy density scales with the inverse cube of the scale factor, i.e., ρ ∝ a−3. This is in contrast to radiation, which scales as the inverse fourth power of the scale factor ρ ∝ a−4 , and a cosmological constant, which is independent of a.

These scalings can be understood intuitively: for an ordinary particle

in a cubical box, doubling the length of the sides of the box decreases

the density (and hence energy density) by a factor of eight (23). For radiation, the decrease in energy density is larger because an increase in scale factor causes a proportional redshift.

A cosmological constant, as an intrinsic property of space, has a

constant energy density regardless of the volume under consideration.

In principle, "dark matter" means all components of the universe that are not visible but still obey ρ ∝ a−3. In practice, the term "dark matter" is often used to mean only the non-baryonic component of dark matter, i.e., excluding "missing baryons." Context will usually indicate which meaning is intended.

Observational evidence

This artist's impression shows the expected distribution of dark matter in the Milky Way galaxy as a blue halo of material surrounding the galaxy.

Galaxy rotation curves

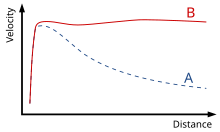

Rotation curve of a typical spiral galaxy: predicted (A) and observed (B). Dark matter can explain the 'flat' appearance of the velocity curve out to a large radius.

The arms of spiral galaxies

rotate around the galactic center. The luminous mass density of a

spiral galaxy decreases as one goes from the center to the outskirts. If

luminous mass were all the matter, then we can model the galaxy as a

point mass in the centre and test masses orbiting around it, similar to

the Solar System. From Kepler's Second Law,

it is expected that the rotation velocities will decrease with distance

from the center, similar to the Solar System. This is not observed. Instead, the galaxy rotation curve remains flat as distance from the center increases.

If Kepler's laws are correct, then the obvious way to resolve

this discrepancy is to conclude that the mass distribution in spiral

galaxies is not similar to that of the Solar System. In particular,

there is a lot of non-luminous matter (dark matter) in the outskirts of

the galaxy.

Velocity dispersion

Stars in bound systems must obey the virial theorem.

The theorem, together with the measured velocity distribution, can be

used to measure the mass distribution in a bound system, such as

elliptical galaxies or globular clusters. With some exceptions, velocity

dispersion estimates of elliptical galaxies

do not match the predicted velocity dispersion from the observed mass

distribution, even assuming complicated distributions of stellar orbits.

As with galaxy rotation curves, the obvious way to resolve the discrepancy is to postulate the existence of non-luminous matter.

Galaxy clusters

Galaxy clusters are particularly important for dark matter studies since their masses can be estimated in three independent ways:

- From the scatter in radial velocities of the galaxies within clusters

- From X-rays emitted by hot gas in the clusters. From the X-ray energy spectrum and flux, the gas temperature and density can be estimated, hence giving the pressure; assuming pressure and gravity balance determines the cluster's mass profile.

- Gravitational lensing (usually of more distant galaxies) can measure cluster masses without relying on observations of dynamics (e.g., velocity).

Generally, these three methods are in reasonable agreement that dark matter outweighs visible matter by approximately 5 to 1.

Gravitational lensing

Strong gravitational lensing as observed by the Hubble Space Telescope in Abell 1689 indicates the presence of dark matter—enlarge the image to see the lensing arcs.

Dark matter map for a patch of sky based on gravitational lensing analysis of a Kilo-Degree survey.

One of the consequences of general relativity is that massive objects (such as a cluster of galaxies) lying between a more distant source (such as a quasar)

and an observer should act as a lens to bend the light from this

source. The more massive an object, the more lensing is observed.

Strong lensing is the observed distortion of background galaxies

into arcs when their light passes through such a gravitational lens. It

has been observed around many distant clusters including Abell 1689.

By measuring the distortion geometry, the mass of the intervening

cluster can be obtained. In the dozens of cases where this has been

done, the mass-to-light ratios obtained correspond to the dynamical dark

matter measurements of clusters.

Lensing can lead to multiple copies of an image. By analyzing the

distribution of multiple image copies, scientists have been able to

deduce and map the distribution of dark matter around the MACS J0416.1-2403 galaxy cluster.

Weak gravitational lensing investigates minute distortions of galaxies, using statistical analyses from vast galaxy surveys.

By examining the apparent shear deformation of the adjacent background

galaxies, the mean distribution of dark matter can be characterized. The

mass-to-light ratios correspond to dark matter densities predicted by

other large-scale structure measurements. Dark matter does not bend light itself; mass (in this case the mass of the dark matter) bends spacetime. Light follows the curvature of spacetime, resulting in the lensing effect.

Cosmic microwave background

Estimated division of total energy in the universe into matter, dark matter and dark energy based on five years of WMAP data.

Although both dark matter and ordinary matter are matter, they do not

behave in the same way. In particular, in the early universe, ordinary

matter was ionized and interacted strongly with radiation via Thomson scattering.

Dark matter does not interact directly with radiation, but it does

affect the CMB by its gravitational potential (mainly on large scales),

and by its effects on the density and velocity of ordinary matter.

Ordinary and dark matter perturbations, therefore, evolve differently

with time and leave different imprints on the cosmic microwave

background (CMB).

The cosmic microwave background is very close to a perfect

blackbody but contains very small temperature anisotropies of a few

parts in 100,000. A sky map of anisotropies can be decomposed into an

angular power spectrum, which is observed to contain a series of

acoustic peaks at near-equal spacing but different heights.

The series of peaks can be predicted for any assumed set of cosmological

parameters by modern computer codes such as CMBFast and CAMB, and

matching theory to data, therefore, constrains cosmological parameters.

The first peak mostly shows the density of baryonic matter, while the

third peak relates mostly to the density of dark matter, measuring the

density of matter and the density of atoms.

The CMB anisotropy was first discovered by COBE in 1992, though this had too coarse resolution to detect the acoustic peaks.

After the discovery of the first acoustic peak by the balloon-borne BOOMERanG experiment in 2000,

the power spectrum was precisely observed by WMAP in 2003-12, and even more precisely

by the Planck spacecraft in 2013-15. The results support the Lambda-CDM model.

The observed CMB angular power spectrum provides powerful

evidence in support of dark matter, as its precise structure is well

fitted by the Lambda-CDM model, but difficult to reproduce with any competing model such as modified Newtonian dynamics (MOND).

Structure formation

3D map of the large-scale distribution of dark matter, reconstructed from measurements of weak gravitational lensing with the Hubble Space Telescope.

Structure formation refers to the period after the Big Bang when

density perturbations collapsed to form stars, galaxies, and clusters.

Prior to structure formation, the Friedmann solutions

to general relativity describe a homogeneous universe. Later, small

anisotropies gradually grew and condensed the homogeneous universe into

stars, galaxies and larger structures. Ordinary matter is affected by

radiation, which is the dominant element of the universe at very early

times. As a result, its density perturbations are washed out and unable

to condense into structure.

If there were only ordinary matter in the universe, there would not

have been enough time for density perturbations to grow into the

galaxies and clusters currently seen.

Dark matter provides a solution to this problem because it is

unaffected by radiation. Therefore, its density perturbations can grow

first. The resulting gravitational potential acts as an attractive potential well for ordinary matter collapsing later, speeding up the structure formation process.

Bullet Cluster

If dark matter does not exist, then the next most likely explanation

is that general relativity—the prevailing theory of gravity—is

incorrect. The Bullet Cluster, the result of a recent collision of two

galaxy clusters, provides a challenge for modified gravity theories

because its apparent center of mass is far displaced from the baryonic

center of mass. Standard dark matter theory can easily explain this observation, but modified gravity has a much harder time, especially since the observational evidence is model-independent.

Type Ia supernova distance measurements

Type Ia supernovae can be used as standard candles

to measure extragalactic distances, which can in turn be used to

measure how fast the universe has expanded in the past. The data

indicates that the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate, the

cause of which is usually ascribed to dark energy. Since observations indicate the universe is almost flat, it is expected that the total energy density of everything in the universe should sum to 1 (Ωtot ~ 1). The measured dark energy density is ΩΛ = ~0.690; the observed ordinary (baryonic) matter energy density is Ωb = ~0.0482 and the energy density of radiation is negligible. This leaves a missing Ωdm = ~0.258 that nonetheless behaves like matter (see technical definition section above)—dark matter.

Sky surveys and baryon acoustic oscillations

Baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO) are fluctuations in the density of the visible baryonic

matter (normal matter) of the universe on large scales. These are

predicted to arise in the Lambda-CDM model due to acoustic oscillations

in the photon-baryon fluid of the early universe, and can be observed in

the cosmic microwave background angular power spectrum. BAOs set up a

preferred length scale for baryons. As the dark matter and baryons

clumped together after recombination, the effect is much weaker in the

galaxy distribution in the nearby universe, but is detectable as a

subtle (~ 1 percent) preference for pairs of galaxies to be separated by

147 Mpc, compared to those separated by 130 or 160 Mpc. This feature

was predicted theoretically in the 1990s and then discovered in 2005, in

two large galaxy redshift surveys, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and the 2dF Galaxy Redshift Survey. Combining the CMB observations with BAO measurements from galaxy redshift surveys provides a precise estimate of the Hubble constant and the average matter density in the Universe. The results support the Lambda-CDM model.

Redshift-space distortions

Large galaxy redshift surveys

may be used to make a three-dimensional map of the galaxy distribution.

These maps are slightly distorted because distances are estimated from

observed redshifts;

the redshift contains a contribution from the galaxy's so-called

peculiar velocity in addition to the dominant Hubble expansion term. On

average, superclusters are expanding but more slowly than the cosmic

mean due to their gravity, while voids are expanding faster than

average. In a redshift map, galaxies in front of a supercluster have

excess radial velocities towards it and have redshifts slightly higher

than their distance would imply, while galaxies behind the supercluster

have redshifts slightly low for their distance. This effect causes

superclusters to appear squashed in the radial direction, and likewise

voids are stretched. Their angular positions are unaffected.

The effect is not detectable for any one structure since the true shape

is not known, but can be measured by averaging over many structures

assuming Earth is not at a special location in the Universe.

The effect was predicted quantitatively by Nick Kaiser in 1987, and first decisively measured in 2001 by the 2dF Galaxy Redshift Survey. Results are in agreement with the Lambda-CDM model.

Lyman-alpha forest

In astronomical spectroscopy, the Lyman-alpha forest is the sum of the absorption lines arising from the Lyman-alpha transition of neutral hydrogen in the spectra of distant galaxies and quasars. Lyman-alpha forest observations can also constrain cosmological models. These constraints agree with those obtained from WMAP data.

Composition of dark matter: baryonic vs. nonbaryonic

There are various hypotheses about what dark matter could consist of, as set out in the table below.

| Some dark matter hypotheses | |

|---|---|

| Light bosons | quantum chromodynamics axions |

| axion-like particles | |

| fuzzy cold dark matter | |

| neutrinos | Standard Model |

| sterile neutrinos | |

| weak scale | supersymmetry |

| extra dimensions | |

| little Higgs | |

| effective field theory | |

| simplified models | |

| other particles | WIMPzilla |

| self-interacting dark matter | |

| superfluid vacuum theory | |

| macroscopic | primordial black holes |

| massive compact halo objects (MaCHOs) | |

| Macroscopic dark matter (Macros) | |

| modified gravity (MOG) | modified Newtonian dynamics (MoND) |

| Tensor–vector–scalar gravity (TeVeS) | |

| Entropic gravity | |

Dark matter can refer to any substance that interacts predominantly

via gravity with visible matter (e.g., stars and planets). Hence in

principle it need not be composed of a new type of fundamental particle

but could, at least in part, be made up of standard baryonic matter,

such as protons or neutrons.

However, for the reasons outlined below, most scientists think the dark

matter is dominated by a non-baryonic component, which is likely

composed of a currently unknown fundamental particle (or similar exotic

state).

Fermi-LAT observations of dwarf galaxies provide new insights on dark matter.

Baryonic matter

Baryons (protons and neutrons) make up ordinary stars and planets. However, baryonic matter also encompasses less common black holes, neutron stars, faint old white dwarfs and brown dwarfs, collectively known as massive compact halo objects (MACHOs), which can be hard to detect.

However, multiple lines of evidence suggest the majority of dark matter is not made of baryons:

- Sufficient diffuse, baryonic gas or dust would be visible when backlit by stars.

- The theory of Big Bang nucleosynthesis predicts the observed abundance of the chemical elements. If there are more baryons, then there should also be more helium, lithium and heavier elements synthesized during the Big Bang. Agreement with observed abundances requires that baryonic matter makes up between 4–5% of the universe's critical density. In contrast, large-scale structure and other observations indicate that the total matter density is about 30% of the critical density.

- Astronomical searches for gravitational microlensing in the Milky Way found that at most a small fraction of the dark matter may be in dark, compact, conventional objects (MACHOs, etc.); the excluded range of object masses is from half the Earth's mass up to 30 solar masses, which covers nearly all the plausible candidates.

- Detailed analysis of the small irregularities (anisotropies) in the cosmic microwave background. Observations by WMAP and Planck indicate that around five sixths of the total matter is in a form that interacts significantly with ordinary matter or photons only through gravitational effects.

Non-baryonic matter

Candidates for non-baryonic dark matter are hypothetical particles such as axions, sterile neutrinos, weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs), gravitationally-interacting massive particles (GIMPs), or supersymmetric

particles. The three neutrino types already observed are indeed

abundant, and dark, and matter, but because their individual

masses—however uncertain they may be—are almost certainly tiny, they can

only supply a small fraction of dark matter, due to limits derived from

large-scale structure and high-redshift galaxies.

Unlike baryonic matter, nonbaryonic matter did not contribute to the formation of the elements in the early universe (Big Bang nucleosynthesis) and so its presence is revealed only via its gravitational effects, or weak lensing. In addition, if the particles of which it is composed are supersymmetric, they can undergo annihilation interactions with themselves, possibly resulting in observable by-products such as gamma rays and neutrinos (indirect detection).

Dark matter aggregation and dense dark matter objects

If dark matter is as common as observations suggest, an obvious question is whether it can form objects equivalent to planets, stars, or black holes. The answer has historically been that it cannot, because of two factors:

- It lacks an efficient means to lose energy: Ordinary matter forms dense objects because it has numerous ways to lose energy. Losing energy would be essential for object formation, because a particle that gains energy during compaction or falling "inward" under gravity, and cannot lose it any other way, will heat up and increase velocity and momentum. Dark matter appears to lack means to lose energy, simply because it is not capable of interacting strongly in other ways except through gravity. The Virial theorem suggests that such a particle would not stay bound to the gradually forming object—as the object began to form and compact, the dark matter particles within it would speed up and tend to escape.

- It lacks a range of interactions needed to form structures: Ordinary matter interacts in many different ways. This allow it to form more complex structures. For example, stars form through gravity, but the particles within them interact and can emit energy in the form of neutrinos and electromagnetic radiation through fusion when they become energetic enough. Protons and neutrons can bind via the strong interaction and then form atoms with electrons largely through electromagnetic interaction. But there is no evidence that dark matter is capable of such a wide variety of interactions, since it only seems to interact through gravity and through some means no stronger than the weak interaction (although this is speculative until dark matter is better understood).

In 2015–2017 the idea that dense dark matter was composed of primordial black holes, made a comeback following results of gravitation wave

measurements which detected the merger of intermediate mass black

holes. Black holes with about 30 solar masses are not predicted to form

by either stellar collapse (typically less than 15 solar masses) or by

the merger of black holes in galactic centers (millions or billions of

solar masses). It was proposed that the intermediate mass black holes

causing the detected merger formed in the hot dense early phase of the

universe due to denser regions collapsing. However this was later ruled

out by a survey of about a thousand supernova which detected no

gravitational lensing events, although about 8 would be expected if

intermediate mass primordial black holes accounted for the majority of

dark matter.

The possibility that atom-sized primordial black holes account for a

significant fraction of dark matter was ruled out by measurements of

positron and electron fluxes outside the suns heliosphere by the Voyager

1 spacecraft. Tiny black holes are theorized to emit Hawking radiation.

However the detected fluxes were too low and did not have the expected

energy spectrum suggesting that tiny primordial black holes are not

widespread enough to account for dark matter.

None-the-less research and theories proposing that dense dark matter

account for dark matter continue as of 2018, including approaches to

dark matter cooling, and the question remains unsettled.

Classification of dark matter: cold, warm or hot

Dark matter can be divided into cold, warm, and hot categories.

These categories refer to velocity rather than an actual temperature,

indicating how far corresponding objects moved due to random motions in

the early universe, before they slowed due to cosmic expansion—this is

an important distance called the free streaming

length (FSL). Primordial density fluctuations smaller than this length

get washed out as particles spread from overdense to underdense regions,

while larger fluctuations are unaffected; therefore this length sets a

minimum scale for later structure formation. The categories are set with

respect to the size of a protogalaxy

(an object that later evolves into a dwarf galaxy): dark matter

particles are classified as cold, warm, or hot according to their FSL;

much smaller (cold), similar to (warm), or much larger (hot) than a

protogalaxy.

Mixtures of the above are also possible: a theory of mixed dark matter was popular in the mid-1990s, but was rejected following the discovery of dark energy.

Cold dark matter leads to a bottom-up formation of structure with

galaxies forming first and galaxy clusters at a latter stage, while hot

dark matter would result in a top-down formation scenario with large

matter aggregations forming early, later fragmenting into separate

galaxies; the latter is excluded by high-redshift galaxy observations.

Alternative definitions

These categories also correspond to fluctuation spectrum effects and the interval following the Big Bang at which each type became non-relativistic. Davis et al. wrote in 1985:

Candidate particles can be grouped into three categories on the basis of their effect on the fluctuation spectrum (Bond et al. 1983). If the dark matter is composed of abundant light particles which remain relativistic until shortly before recombination, then it may be termed "hot". The best candidate for hot dark matter is a neutrino ... A second possibility is for the dark matter particles to interact more weakly than neutrinos, to be less abundant, and to have a mass of order 1 keV. Such particles are termed "warm dark matter", because they have lower thermal velocities than massive neutrinos ... there are at present few candidate particles which fit this description. Gravitinos and photinos have been suggested (Pagels and Primack 1982; Bond, Szalay and Turner 1982) ... Any particles which became nonrelativistic very early, and so were able to diffuse a negligible distance, are termed "cold" dark matter (CDM). There are many candidates for CDM including supersymmetric particles.

— M. Davis, G. Efstathiou, C. S. Frenk, and S. D. M. White, The evolution of large-scale structure in a universe dominated by cold dark matter

Another approximate dividing line is that warm dark matter became

non-relativistic when the universe was approximately 1 year old and 1

millionth of its present size and in the radiation-dominated era (photons and neutrinos), with a photon temperature 2.7 million K. Standard physical cosmology gives the particle horizon size as 2ct

(speed of light multiplied by time) in the radiation-dominated era,

thus 2 light-years. A region of this size would expand to 2 million

light-years today (absent structure formation). The actual FSL is

approximately 5 times the above length, since it continues to grow

slowly as particle velocities decrease inversely with the scale factor

after they become non-relativistic. In this example the FSL would

correspond to 10 million light-years, or 3 megaparsecs, today, around the size containing an average large galaxy.

The 2.7 million K photon temperature gives a typical photon

energy of 250 electron-volts, thereby setting a typical mass scale for

warm dark matter: particles much more massive than this, such as GeV–TeV

mass WIMPs,

would become non-relativistic much earlier than one year after the Big

Bang and thus have FSLs much smaller than a protogalaxy, making them

cold. Conversely, much lighter particles, such as neutrinos with masses

of only a few eV, have FSLs much larger than a protogalaxy, thus

qualifying them as hot.

Cold dark matter

Cold dark matter

offers the simplest explanation for most cosmological observations. It

is dark matter composed of constituents with an FSL much smaller than a

protogalaxy. This is the focus for dark matter research, as hot dark

matter does not seem capable of supporting galaxy or galaxy cluster

formation, and most particle candidates slowed early.

The constituents of cold dark matter are unknown. Possibilities range from large objects like MACHOs (such as black holes and Preon stars) or RAMBOs (such as clusters of brown dwarfs), to new particles such as WIMPs and axions.

Studies of Big Bang nucleosynthesis and gravitational lensing convinced most cosmologists that MACHOs cannot make up more than a small fraction of dark matter. According to A. Peter: "... the only really plausible dark-matter candidates are new particles."

Specifically, Jamie Farnes proposes a particle with negative mass.

The 1997 DAMA/NaI experiment and its successor DAMA/LIBRA

in 2013, claimed to directly detect dark matter particles passing

through the Earth, but many researchers remain skeptical, as negative

results from similar experiments seem incompatible with the DAMA

results.

Many supersymmetric models offer dark matter candidates in the form of the WIMPy Lightest Supersymmetric Particle (LSP). Separately, heavy sterile neutrinos exist in non-supersymmetric extensions to the standard model that explain the small neutrino mass through the seesaw mechanism.

Warm dark matter

Warm dark matter

comprises particles with an FSL comparable to the size of a

protogalaxy. Predictions based on warm dark matter are similar to those

for cold dark matter on large scales, but with less small-scale density

perturbations. This reduces the predicted abundance of dwarf galaxies

and may lead to lower density of dark matter in the central parts of

large galaxies. Some researchers consider this a better fit to

observations. A challenge for this model is the lack of particle

candidates with the required mass ~ 300 eV to 3000 eV.

No known particles can be categorized as warm dark matter. A postulated candidate is the sterile neutrino: a heavier, slower form of neutrino that does not interact through the weak force, unlike other neutrinos. Some modified gravity theories, such as scalar–tensor–vector gravity, require "warm" dark matter to make their equations work.

Hot dark matter

Hot dark matter consists of particles whose FSL is much larger than the size of a protogalaxy. The neutrino

qualifies as such particle. They were discovered independently, long

before the hunt for dark matter: they were postulated in 1930, and detected in 1956. Neutrinos' mass is less than 10−6 that of an electron. Neutrinos interact with normal matter only via gravity and the weak force,

making them difficult to detect (the weak force only works over a small

distance, thus a neutrino triggers a weak force event only if it hits a

nucleus head-on). This makes them 'weakly interacting light particles'

(WILPs), as opposed to WIMPs.

The three known flavours of neutrinos are the electron, muon, and tau. Their masses are slightly different. Neutrinos oscillate among the flavours as they move. It is hard to determine an exact upper bound

on the collective average mass of the three neutrinos (or for any of

the three individually). For example, if the average neutrino mass were

over 50 eV/c2 (less than 10−5 of the mass

of an electron), the universe would collapse. CMB data and other methods

indicate that their average mass probably does not exceed 0.3 eV/c2. Thus, observed neutrinos cannot explain dark matter.

Because galaxy-size density fluctuations get washed out by

free-streaming, hot dark matter implies that the first objects that can

form are huge supercluster-size pancakes, which then fragment into galaxies. Deep-field observations show instead that galaxies formed first, followed by clusters and superclusters as galaxies clump together.

Detection of dark matter particles

If

dark matter is made up of sub-atomic particles, then millions, possibly

billions, of such particles must pass through every square centimeter

of the Earth each second. Many experiments aim to test this hypothesis. Although WIMPs are popular search candidates, the Axion Dark Matter Experiment (ADMX) searches for axions. Another candidate is heavy hidden sector particles that only interact with ordinary matter via gravity.

These experiments can be divided into two classes: direct

detection experiments, which search for the scattering of dark matter

particles off atomic nuclei within a detector; and indirect detection,

which look for the products of dark matter particle annihilations or

decays.

Direct detection

Direct detection experiments aim to observe low-energy recoils (typically a few keVs)

of nuclei induced by interactions with particles of dark matter, which

(in theory) are passing through the Earth. After such a recoil the

nucleus will emit energy as, e.g., scintillation light or phonons,

which is then detected by sensitive apparatus. To do this effectively,

it is crucial to maintain a low background, and so such experiments

operate deep underground to reduce the interference from cosmic rays. Examples of underground laboratories with direct detection experiments include the Stawell mine, the Soudan mine, the SNOLAB underground laboratory at Sudbury, the Gran Sasso National Laboratory, the Canfranc Underground Laboratory, the Boulby Underground Laboratory, the Deep Underground Science and Engineering Laboratory and the China Jinping Underground Laboratory.

These experiments mostly use either cryogenic or noble liquid

detector technologies. Cryogenic detectors operating at temperatures

below 100 mK, detect the heat produced when a particle hits an atom in a

crystal absorber such as germanium. Noble liquid detectors detect scintillation produced by a particle collision in liquid xenon or argon. Cryogenic detector experiments include: CDMS, CRESST, EDELWEISS, EURECA. Noble liquid experiments include ZEPLIN, XENON, DEAP, ArDM, WARP, DarkSide, PandaX, and LUX, the Large Underground Xenon experiment.

Both of these techniques focus strongly on their ability to distinguish

background particles (which predominantly scatter off electrons) from

dark matter particles (that scatter off nuclei). Other experiments

include SIMPLE and PICASSO.

Currently there has been no well-established claim of dark matter

detection from a direct detection experiment, leading instead to strong

upper limits on the mass and interaction cross section with nucleons of

such dark matter particles. The DAMA/NaI and more recent DAMA/LIBRA experimental collaborations have detected an annual modulation in the rate of events in their detectors,

which they claim is due to dark matter. This results from the

expectation that as the Earth orbits the Sun, the velocity of the

detector relative to the dark matter halo

will vary by a small amount. This claim is so far unconfirmed and in

contradiction with negative results from other experiments such as LUX

and SuperCDMS.

A special case of direct detection experiments covers those with

directional sensitivity. This is a search strategy based on the motion

of the Solar System around the Galactic Center. A low-pressure time projection chamber

makes it possible to access information on recoiling tracks and

constrain WIMP-nucleus kinematics. WIMPs coming from the direction in

which the Sun travels (approximately towards Cygnus) may then be separated from background, which should be isotropic. Directional dark matter experiments include DMTPC, DRIFT, Newage and MIMAC.

Indirect detection

Collage

of six cluster collisions with dark matter maps. The clusters were

observed in a study of how dark matter in clusters of galaxies behaves

when the clusters collide.

Indirect detection experiments search for the products of the

self-annihilation or decay of dark matter particles in outer space. For

example, in regions of high dark matter density (e.g., the center of our galaxy) two dark matter particles could annihilate to produce gamma rays or Standard Model particle-antiparticle pairs.

Alternatively if the dark matter particle is unstable, it could decay

into standard model (or other) particles. These processes could be

detected indirectly through an excess of gamma rays, antiprotons or positrons emanating from high density regions in our galaxy or others.

A major difficulty inherent in such searches is that various

astrophysical sources can mimic the signal expected from dark matter,

and so multiple signals are likely required for a conclusive discovery.

A few of the dark matter particles passing through the Sun or

Earth may scatter off atoms and lose energy. Thus dark matter may

accumulate at the center of these bodies, increasing the chance of

collision/annihilation. This could produce a distinctive signal in the

form of high-energy neutrinos. Such a signal would be strong indirect proof of WIMP dark matter. High-energy neutrino telescopes such as AMANDA, IceCube and ANTARES are searching for this signal.

The detection by LIGO in September 2015 of gravitational waves, opens the possibility of observing dark matter in a new way, particularly if it is in the form of primordial black holes.

Many experimental searches have been undertaken to look for such

emission from dark matter annihilation or decay, examples of which

follow.

The Energetic Gamma Ray Experiment Telescope observed more gamma rays in 2008 than expected from the Milky Way, but scientists concluded that this was most likely due to incorrect estimation of the telescope's sensitivity.

The Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope is searching for similar gamma rays. In April 2012, an analysis of previously available data from its Large Area Telescope instrument produced statistical evidence of a 130 GeV signal in the gamma radiation coming from the center of the Milky Way. WIMP annihilation was seen as the most probable explanation.

At higher energies, ground-based gamma-ray telescopes have set limits on the annihilation of dark matter in dwarf spheroidal galaxies and in clusters of galaxies.

The PAMELA experiment (launched in 2006) detected excess positrons. They could be from dark matter annihilation or from pulsars. No excess antiprotons were observed.

In 2013 results from the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer on the International Space Station indicated excess high-energy cosmic rays that could be due to dark matter annihilation.

Collider searches for dark matter

An

alternative approach to the detection of dark matter particles in

nature is to produce them in a laboratory. Experiments with the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) may be able to detect dark matter particles produced in collisions of the LHC proton

beams. Because a dark matter particle should have negligible

interactions with normal visible matter, it may be detected indirectly

as (large amounts of) missing energy and momentum that escape the

detectors, provided other (non-negligible) collision products are

detected.

Constraints on dark matter also exist from the LEP experiment using a similar principle, but probing the interaction of dark matter particles with electrons rather than quarks.

It is important to note that any discovery from collider searches must

be corroborated by discoveries in the indirect or direct detection

sectors to prove that the particle discovered is, in fact, dark matter.

Alternative hypotheses

Because dark matter remains to be conclusively identified, many other

hypotheses have emerged aiming to explain the observational phenomena

that dark matter was conceived to explain. The most common method is to

modify general relativity. General relativity is well-tested on solar

system scales, but its validity on galactic or cosmological scales has

not been well proven. A suitable modification to general relativity can

conceivably eliminate the need for dark matter. The best-known theories

of this class are MOND and its relativistic generalization tensor-vector-scalar gravity (TeVeS), f(R) gravity and entropic gravity. Alternative theories abound.

A problem with alternative hypotheses is that the observational

evidence for dark matter comes from so many independent approaches (see

the "observational evidence" section above). Explaining any individual

observation is possible but explaining all of them is very difficult.

Nonetheless, there have been some scattered successes for alternative

hypotheses, such as a 2016 test of gravitational lensing in entropic

gravity.

The prevailing opinion among most astrophysicists is that while

modifications to general relativity can conceivably explain part of the

observational evidence, there is probably enough data to conclude there

must be some form of dark matter.

In philosophy of science

In philosophy of science, dark matter is an example of an auxiliary hypothesis, an ad hoc postulate that is added to a theory in response to observations that falsify it. It has been argued that the dark matter hypothesis is a conventionalist hypothesis, that is, a hypothesis that adds no empirical content and hence is unfalsifiable in the sense defined by Karl Popper.

In popular culture

Mention of dark matter is made in works of fiction. In such cases, it

is usually attributed extraordinary physical or magical properties.

Such descriptions are often inconsistent with the hypothesized

properties of dark matter in physics and cosmology.