Erasmus of Rotterdam was a foremost intellectual of his time.

The French-American intellectual Jacques Barzun was a teacher, a man of letters, and a scholar.

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about society and proposes solutions for its normative problems, and gain authority as public intellectuals. Coming from the world of culture,

either as a creator or as a mediator, the intellectual participates in

politics either to defend a concrete proposition or to denounce an

injustice, usually by rejecting, producing or extending an ideology, and by defending a system of values.

Definition

The intellectual is a type of intelligent person, who is associated with reason and critical thinking. Many everyday roles require the application of intelligence to skills that may have a psychomotor

component, for example, in the fields of medicine or the arts, but

these do not necessarily involve the practitioner in the "world of

ideas". The distinctive quality of the intellectual person is that the

mental skills, which one demonstrates, are not simply intelligent, but

even more, they focus on thinking about the abstract, philosophical and esoteric aspects of human inquiry and the value of their thinking.

The intellectual and the scholarly classes are related; the intellectual usually is not a teacher involved in the production of scholarship,

but has an academic background, and works in a profession, practices an

art, or a science. The intellectual person is one who applies critical thinking and reason in either a professional or a personal capacity, and so has authority in the public sphere of their society; the term intellectual identifies three types of person, one who:

- is erudite, and develops abstract ideas and theories

- a professional who produces cultural capital, as in philosophy, literary criticism, sociology, law, medicine, science, and

- an artist who writes, composes, paints, etc.

Historical definitions

In Latin language, at least starting from the Carolingian Empire, they could be called litterati, a term which is sometimes applied until this day.

Socially, intellectuals constitute the intelligentsia, a status class organised either by ideology (conservative, fascist, socialist, liberal, reactionary, revolutionary, democratic, communist intellectuals, et al.), or by nationality (American intellectuals, French intellectuals, Ibero–American intellectuals, et al.). The contemporary intellectual class originated from the intelligentsiya of Tsarist Russia (c. 1860s–1870s), the social stratum of those possessing intellectual formation (schooling, education, Enlightenment), and who were Russian society's counterpart to the German Bildungsbürgertum and to the French bourgeoisie éclairée, the enlightened middle classes of those realms.

In the late 19th century, amidst the Dreyfus affair (1894–1906), an identity crisis of anti-semitic nationalism for the French Third Republic (1870–1940), the reactionary anti–Dreyfusards (Maurice Barrès, Ferdinand Brunetière, et al.) used the terms intellectual and the intellectuals to deride the liberal Dreyfusards (Émile Zola, Octave Mirbeau, Anatole France, et al.)

as political dilettantes from the realms of French culture, art, and

science, who had become involved in politics, by publicly advocating for

the exoneration and liberation of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish French artillery captain falsely accused of betraying France to Germany.

In the 20th century, the term Intellectual acquired positive connotations of social prestige, derived from possessing intellect and intelligence, especially when the intellectual's activities exerted positive consequences in the public sphere and so increased the intellectual understanding of the public, by means of moral responsibility, altruism, and solidarity, without resorting to the manipulations of demagoguery, paternalism, and incivility (condescension).

Hence, for the educated person of a society, participating in the

public sphere—the political affairs of the city-state—is a civic

responsibility dating from the Græco–Latin Classical era:

I am a human; I reckon nothing human to be foreign to me. (Homo sum: humani nihil a me alienum puto.)

— The Self-Tormentor (163 BC), Terence

The determining factor for a Thinker (historian, philosopher, scientist, writer, artist, et al.) to be considered a public intellectual is the degree to which he or she is implicated and engaged

with the vital reality of the contemporary world; that is to say,

participation in the public affairs of society. Consequently, being

designated as a public intellectual is determined by the degree of

influence of the designator's motivations, opinions, and options of action (social, political, ideological), and by affinity with the given thinker; therefore:

The Intellectual is someone who meddles in what does not concern them. (L'intellectuel est quelqu'un qui se mêle de ce qui ne le regarde pas.)

Analogously, the application and the conceptual value of the terms Intellectual and the Intellectuals are socially negative when the practice of intellectuality is exclusively in service to The Establishment who wield power in a society, as such:

The Intellectuals are specialists in defamation, they are basically political commissars, they are the ideological administrators, the most threatened by dissidence.

Noam Chomsky's negative view of the Establishment Intellectual

suggests the existence of another kind of intellectual one might call

"the public intellectual," which is:

... someone able to speak the truth, a ... courageous and angry individual for whom no worldly power is too big and imposing to be criticised and pointedly taken to task. The real or true intellectual is therefore always an outsider, living in self-imposed exile, and on the margins of society. He or she speaks to, as well as for, a public, necessarily in public, and is properly on the side of the dispossessed, the un-represented and the forgotten.

"Man of letters"

The term "man of letters" derives from the French term belletrist or homme de lettres but is not synonymous with "an academic". A "man of letters" was a literate man ("able to read and write") as opposed to an illiterate man, in a time when literacy was a rare form of cultural capital. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Belletrists were the literati, the French "citizens of the Republic of Letters", which evolved into the salon,

a social institution, usually run by a hostess, meant for the

edification, education, and cultural refinement of the participants.

Historical background

In English, the term intellectual identifies a "literate thinker"; its earlier usage, as in the book title The Evolution of an Intellectual (1920), by John Middleton Murry, denotes literary activity, rather than the activities of the public intellectual.

19th-century

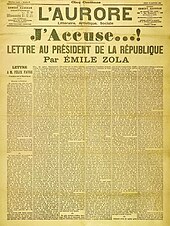

The front page of L'Aurore (13 January 1898) featured Émile Zola's open letter, J'Accuse…!, asking the French President, Félix Faure, to resolve the Dreyfus affair.

Britain

In the late 19th century, when literacy was relatively common in European countries such as the United Kingdom, the "Man of Letters" (littérateur)

denotation broadened to mean "specialized", a man who earned his living

writing intellectually (not creatively) about literature: the essayist, the journalist, the critic,

et al. In the 20th century, such an approach was gradually superseded

by the academic method, and the term "Man of Letters" became disused,

replaced by the generic term "intellectual", describing the intellectual

person. In late 19th century, the term intellectual became common usage to denote the defenders of the falsely accused artillery officer Alfred Dreyfus.

Continental Europe

In early 19th century Britain, Samuel Taylor Coleridge coined the term clerisy,

the intellectual class responsible for upholding and maintaining the

national culture, the secular equivalent of the Anglican clergy.

Likewise, in Tsarist Russia, there arose the intelligentsia (1860s–70s), who were the status class of white-collar workers. The theologian Alister McGrath said that "the emergence of a socially alienated, theologically literate, antiestablishment lay intelligentsia is one of the more significant phenomena of the social history of Germany in the 1830s", and that "three or four theological graduates in ten might hope to find employment" in a church post. As such, politically radical thinkers already had participated in the French Revolution (1789–1799); Robert Darnton said that they were not societal outsiders, but "respectable, domesticated, and assimilated".

Thenceforth, in Europe, an intellectual class was socially

important, especially to self-styled intellectuals, whose participation

in society's arts, politics, journalism, and education—of either nationalist, internationalist,

or ethnic sentiment—constitute "vocation of the intellectual".

Moreover, some intellectuals were anti-academic, despite universities

(the Academy) being synonymous with intellectualism.

In France, the Dreyfus affair marked the full emergence of the "intellectual in public life", especially Émile Zola, Octave Mirbeau, and Anatole France directly addressing the matter of French antisemitism

to the public; thenceforward, "intellectual" became common, yet

occasionally derogatory, usage; its French noun usage is attributed to Georges Clemenceau in 1898.

Germany

Habermas' Structural Transformation of Public Sphere

(1963) made significant contribution to the notion of public

intellectual by historically and conceptually delineating the idea of

private and public.

In the East

In Imperial China, in the period from 206 BC until AD 1912, the intellectuals were the Scholar-officials ("Scholar-gentlemen"), who were civil servants appointed by the Emperor of China to perform the tasks of daily governance. Such civil servants earned academic degrees by means of imperial examination, and also were skilled calligraphers, and knew Confucian philosophy. Historian Wing-Tsit Chan concludes that:

Generally speaking, the record of these scholar-gentlemen has been a worthy one. It was good enough to be praised and imitated in 18th century Europe. Nevertheless, it has given China a tremendous handicap in their transition from government by men to government by law, and personal considerations in Chinese government have been a curse.

In Joseon Korea (1392–1910), the intellectuals were the literati, who knew how to read and write, and had been designated, as the chungin (the "middle people"), in accordance with the Confucian system. Socially, they constituted the petite bourgeoisie,

composed of scholar-bureaucrats (scholars, professionals, and

technicians) who administered the dynastic rule of the Joseon dynasty.

Intelligentsia

Addressing their role as a social class, Jean-Paul Sartre

said that intellectuals are the moral conscience of their age; that

their moral and ethical responsibilities are to observe the

socio-political moment, and to freely speak to their society, in

accordance with their consciences. Like Sartre and Noam Chomsky, public intellectuals usually are polymaths, knowledgeable of the international order

of the world, the political and economic organization of contemporary

society, the institutions and laws that regulate the lives of the layman

citizen, the educational systems, and the private networks of mass communication media that control the broadcasting of information to the public.

Whereas, intellectuals (political scientists and sociologists),

liberals, and democratic socialists usually hold, advocate, and support

the principles of democracy (liberty, equality, fraternity, human

rights, social justice, social welfare, environmental conservation), and

the improvement of socio-political relations in domestic and

international politics, the conservative public-intellectuals usually defend the social, economic, and political status quo as the realisation of the "perfect ideals" of Platonism, and present a static dominant ideology, in which utopias are unattainable and politically destabilizing of society.

Marxist perspective

In Marxist philosophy, the social class function of the intellectuals (the intelligentsia)

is to be the source of progressive ideas for the transformation of

society; to provide advice and counsel to the political leaders; to

interpret the country's politics to the mass of the population (urban

workers and peasants); and, as required, to provide leaders from within

their own ranks.

The Italian Communist theoretician Antonio Gramsci

(1891–1937) developed Karl Marx's conception of the intelligentsia to

include political leadership in the public sphere. That, because "all

knowledge is existentially-based",

the intellectuals, who create and preserve knowledge, are "spokesmen

for different social groups, and articulate particular social

interests". That intellectuals occur in each social class and throughout

the right wing, the centre, and the left wing of the political

spectrum. That, as a social class, the "intellectuals view themselves as

autonomous from the ruling class" of their society. That, in the course of class struggle meant to achieve political power, every social class requires a native intelligentsia who shape the ideology

(world view) particular to the social class from which they originated.

Therefore, the leadership of intellectuals is required for effecting

and realizing social change, because:

A human mass does not "distinguish" itself, does not become independent, in its own right, without, in the widest sense, organizing itself; and there is no organisation without intellectuals, that is, without organizers and leaders, in other words, without ... a group of people "specialized" in [the] conceptual and philosophical elaboration of ideas.

In the pamphlet What Is to Be Done? (1902), Lenin (1870–1924) said that vanguard-party revolution required the participation of the intellectuals to explain the complexities of socialist ideology to the uneducated proletariat

and the urban industrial workers, in order to integrate them to the

revolution; because "the history of all countries shows that the working

class, exclusively by its own efforts, is able to develop only trade-union consciousness", and will settle for the limited, socio-economic gains so achieved. In Russia, as in Continental Europe,

Socialist theory was the product of the "educated representatives of

the propertied classes", of "revolutionary socialist intellectuals",

such as were Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

In the formal codification of Leninism, the Hungarian Marxist philosopher, György Lukács

(1885–1971) identified the intelligentsia as the privileged social

class who provide revolutionary leadership. By means of intelligible and

accessible interpretation, the intellectuals explain to the workers and

peasants the "Who?", the "How?", and the "Why?" of the social,

economic, and political status quo—the ideological totality of society—and its practical, revolutionary application to the transformation of their society.

Public intellectual

The term public intellectual describes the intellectual participating in the public-affairs discourse of society, in addition to an academic career. Regardless of the academic field or the professional expertise, the public intellectual addresses and responds to the normative

problems of society, and, as such, is expected to be an impartial

critic who can "rise above the partial preoccupation of one's own

profession—and engage with the global issues of truth, judgment, and taste of the time." In Representations of the Intellectual (1994), In summarizing a quote by Edward Saïd,

Jennings and Kemp-Welch state that the "… true intellectual is,

therefore, always an outsider, living in self-imposed exile, and on the

margins of society".

An intellectual usually is associated with an ideology or with a philosophy; e.g., the Third Way centrism of Anthony Giddens in the Labour Government of Tony Blair. The Czech intellectual Václav Havel

said that politics and intellectuals can be linked, but that moral

responsibility for the intellectual's ideas, even when advocated by a

politician, remains with the intellectual. Therefore, it is best to

avoid utopian intellectuals who offer 'universal insights' to resolve the problems of political economy with public policies

that might harm and that have harmed civil society; that intellectuals

be mindful of the social and cultural ties created with their words,

insights, and ideas; and should be heard as social critics of politics and power.

Social background

The American academic Peter H. Smith

describes the intellectuals of Latin America as people from an

identifiable social class, who have been conditioned by that common

experience, and thus are inclined to share a set of common assumptions (values and ethics); that ninety-four per cent of intellectuals come either from the middle class or from the upper class, and that only six per cent come from the working class. In The Intellectual (2005), philosopher Steven Fuller said that, because cultural capital confers power and social status, as a status group, they must be autonomous in order to be credible as intellectuals:

It is relatively easy to demonstrate autonomy, if you come from a wealthy or [an] aristocratic background. You simply need to disown your status and champion the poor and [the] downtrodden ... autonomy is much harder to demonstrate if you come from a poor or proletarian background ... [thus] calls to join the wealthy in common cause appear to betray one's class origins.

The political importance and effective consequence of Émile Zola in the Dreyfus affair (1894–1906) derived from his being a leading French thinker; thus, J'accuse

(I Accuse), his open letter to the French government and the nation

proved critical to achieving the exoneration of Captain Alfred Dreyfus

of the false charges of treason, which were facilitated by institutional

anti-Semitism, among other ideological defects of the French Establishment.

Academic background

In journalism, the term intellectual usually connotes "a university academic" of the humanities—especially a philosopher—who

addresses important social and political matters of the day. Hence,

such an academic functions as a public intellectual who explains the

theoretic bases of said problems and communicates possible answers to

the policy makers and executive leaders of society. The sociologist Frank Furedi

said that "Intellectuals are not defined according to the jobs they do,

but [by] the manner in which they act, the way they see themselves, and

the [social and political] values that they uphold.

Public intellectuals usually arise from the educated élite of a

society; although the North American usage of the term "intellectual"

includes the university academics. The difference between "intellectual" and "academic" is participation in the realm of public affairs.

Public policy role

In the matters of public policy,

the public intellectual connects scholarly research to the practical

matters of solving societal problems. The British sociologist Michael Burawoy, an exponent of public sociology,

said that professional sociology has failed, by giving insufficient

attention to resolving social problems, and that a dialogue between the

academic and the layman would bridge the gap. An example is how Chilean intellectuals worked to reestablish democracy within the right-wing, neoliberal governments of the Military dictatorship of Chile (1973–90),

the Pinochet régime allowed professional opportunities for some liberal

and left-wing social scientists to work as politicians and as

consultants in effort to realize the theoretical economics of the Chicago Boys, but their access to power was contingent upon political pragmatism, abandoning the political neutrality of the academic intellectual.

In The Sociological Imagination (1959), C. Wright Mills

said that academics had become ill-equipped for participating in public

discourse, and that journalists usually are "more politically alert and

knowledgeable than sociologists, economists, and especially ...

political scientists". That, because the universities of the U.S. are bureaucratic, private businesses, they "do not teach critical reasoning to the student", who then does not "how to gauge what is going on in the general struggle for power in modern society". Likewise, Richard Rorty criticized the participation of intellectuals in public discourse as an example of the "civic irresponsibility of intellect, especially academic intellect".

The American legal scholar Richard Posner

said that the participation of academic public intellectuals in the

public life of society is characterized by logically untidy and

politically biased statements of the kind that would be unacceptable to

academia. That there are few ideologically and politically independent

public intellectuals, and disapproves that public intellectuals limit

themselves to practical matters of public policy, and not with values or public philosophy, or public ethics, or public theology, not with matters of moral and spiritual outrage.

Criticism

The economist Milton Friedman identified the intelligentsia and the business class as interfering with the economic functions of a society.

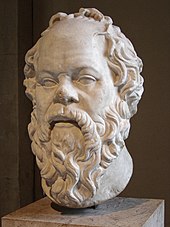

Socrates proposed for philosophers a private monopoly of knowledge separate from the public sphere. (the Louvre)

The Congregational theologian Edwards Amasa Park proposed segregating the intellectuals from the public sphere of society in the U.S.

As an intellectual, Bertrand Russell was a pacifist who advised Britain against re-arming for World War I.

In "An Interview with Milton Friedman" (1974), the American libertarian economist Milton Friedman

said that businessmen and the intellectuals are enemies of capitalism;

the intellectuals, because most believed in socialism, while the

businessman expected economic privileges:

The two, chief enemies of the free society or free enterprise are intellectuals, on the one hand, and businessmen, on the other, for opposite reasons. Every intellectual believes in freedom for himself, but he's opposed to freedom for others. ... He thinks ... [that] there ought to be a central planning board that will establish social priorities. ... The businessmen are just the opposite—every businessman is in favor of freedom for everybody else, but, when it comes to himself that's a different question. He's always "the special case". He ought to get special privileges from the government, a tariff, this, that, and the other thing.

In "The Intellectuals and Socialism" (1949), the British libertarian economist Friedrich Hayek,

said that "journalists, teachers, ministers, lecturers, publicists,

radio commentators, writers of fiction, cartoonists, and artists", are

the intellectual social class whose function is to communicate the

complex and specialized knowledge of the scientist to the general public. That, in the twentieth century, the intellectuals were attracted to socialism and to social democracy, because the socialists offered "broad visions; the spacious comprehension of the social order, as a whole, which a planned system

promises" and that such broad-vision philosophies "succeeded in

inspiring the imagination of the intellectuals" to change and improve

their societies.

According to Hayek, intellectuals disproportionately support socialism for idealistic and utopian reasons that cannot be realized in practical terms. Nonetheless, in the article "Why Socialism?" (1949), Albert Einstein said that the economy of the world is not private property because it is a "planetary community of production and consumption". In U.S. society, the intellectual status class are demographically characterized as people who hold liberal-to-leftist political perspectives about guns-or-butter fiscal policy.

In "The Heartless Lovers of Humankind" (1987), the journalist and popular historian Paul Johnson said:

It is not the formulation of ideas, however misguided, but the desire to impose them on others that is the deadly sin of the intellectuals. That is why they so incline, by temperament, to the Left. For capitalism merely occurs; if no-one does anything to stop it. It is socialism that has to be constructed, and, as a rule, forcibly imposed, thus providing a far bigger role for intellectuals in its genesis. The progressive intellectual habitually entertains Walter Mitty visions of exercising power.

The public- and private-knowledge dichotomy originated in Ancient Greece, from Socrates's rejection of the Sophist concept that the pursuit of knowledge (truth)

is a "public market of ideas", open to all men of the city, not only to

philosophers. In contradiction to the Sophist's public market of

knowledge, Socrates proposed a knowledge monopoly for and by the

philosophers; thus, "those who sought a more penetrating and rigorous

intellectual life rejected, and withdrew from, the general culture of

the city, in order to embrace a new model of professionalism"; the

private market of ideas.

In the 19th century, addressing the societal place, roles, and functions of intellectuals in American society, the Congregational theologian Edwards Amasa Park said, "We do wrong to our own minds, when we carry out scientific difficulties down to the arena of popular dissension". That for the stability of society (social, economic, political) it is necessary "to separate the serious, technical role of professionals from their responsibility [for] supplying usable philosophies

for the general public"; thus operated Socrate's cultural dichotomy of

public-knowledge and private-knowledge, of "civic culture" and

"professional culture", the social constructs that describe and

establish the intellectual sphere of life as separate and apart from the civic sphere of life.

Intelligentsia

The American historian Norman Stone said that the intellectual social class misunderstand the reality of society and so are doomed to the errors of logical fallacy, ideological stupidity, and poor planning hampered by ideology. In her memoirs, the Conservative politician Margaret Thatcher said that the anti-monarchical French Revolution (1789–1799) was "a utopian attempt to overthrow a traditional order ... in the name of abstract ideas, formulated by vain intellectuals".

Yet, as Prime Minister, Thatcher asked Britain's academics to help her

government resolve the social problems of British society—whilst she

retained the populist opinion of "The Intellectual" as being a man of un-British character, a thinker, not a doer; Thatcher's anti-intellectualist perspective was shared by the mass media, especially The Spectator and The Sunday Telegraph newspapers, whose reportage documented a "lack of intellectuals" in Britain.

In his essay "Why do intellectuals oppose capitalism?" (1998), libertarian philosopher Robert Nozick of the Cato Institute argued that intellectuals become embittered leftists because their academic skills, much rewarded at school and at university, are under-valued and under-paid in the capitalist market economy;

so, the intellectuals turned against capitalism—despite enjoying a more

economically and financially comfortable life in a capitalist society

than they might enjoy in either a socialist or a communist society.

In post-Communist Europe, the social attitude perception of the intelligentsia became anti-intellectual; in the Netherlands, the word "intellectual" negatively connotes an overeducated person of "unrealistic visions of the World". In Hungary, the intellectual is perceived as an "egghead", a person who is "too-clever" for the good of society. In the Czech Republic,

the intellectual is a cerebral person, aloof from reality. Such

derogatory connotations of "intellectual" are not definitive, because,

in the "case of English usage, positive, neutral, and pejorative uses

can easily coexist"; the example is Václav Havel

who, "to many outside observers, [became] a favoured instance of The

Intellectual as National Icon" in the early history of the

post-Communist Czech Republic.

In the book, Intellectuals and Society (2010), the economist Thomas Sowell said that, lacking disincentives

in professional life, the intellectual (producer of knowledge, not

material goods) tends to speak outside his or her area of expertise, and

expects social and professional benefits from the halo effect,

derived from possessing professional expertise. That, in relation to

other professions, the public intellectual is socially detached from the

negative and unintended consequences of public policy derived from his or her ideas. As such, the philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) advised the British government against national rearmament in the years before World War I (1914–1918), while the German Empire

prepared for war. Yet, the post-war intellectual reputation of Bertrand

Russell remained almost immaculate and his opinions respected by the

general public because of the halo effect.