|

Scientist looking through a microscope at the NIH National Cancer Institute

| |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names | Scientist |

Occupation type

| Profession |

Activity sectors

| Laboratory, field research |

| Description | |

| Competencies | Scientific research |

Education required

| Science |

Fields of

employment | Academia, industry, government, nonprofit |

Related jobs

| Engineers |

A scientist is someone who conducts scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of interest.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engaged in the philosophical study of nature called natural philosophy, a precursor of natural science. It was not until the 19th century that the term scientist came into regular use after it was coined by the theologian, philosopher, and historian of science William Whewell in 1833. The term 'scientist' was first coined by him for Mary Somerville, partly because the term "man of science", more custom at that time, was clearly inappropriate here.

In modern times, many scientists have advanced degrees in an area of science and pursue careers in various sectors of the economy such as academia, industry, government, and nonprofit environments.

History

"No

one in the history of civilization has shaped our understanding of

science and natural philosophy more than the great Greek philosopher and

scientist Aristotle (384-322 BC), who exerted a profound and pervasive influence for more than two thousand years" —Gary B. Ferngren

Alessandro Volta, the inventor of the electrical battery and discoverer of methane, is widely regarded as one of the greatest scientists in history.

Francesco Redi, referred to as the "father of modern parasitology", is the founder of experimental biology.

Physicist Albert Einstein developed the general theory of relativity and made many substantial contributions to physics.

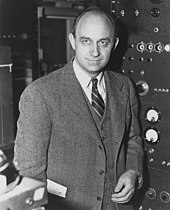

Physicist Enrico Fermi is credited with the creation of the world's first atomic bomb and nuclear reactor.

Atomic physicist Niels Bohr made fundamental contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory.

Marine Biologist Rachel Carson launched the 20th century environmental movement.

The roles of "scientists", and their predecessors before the

emergence of modern scientific disciplines, have evolved considerably

over time. Scientists of different eras (and before them, natural

philosophers, mathematicians, natural historians, natural theologians,

engineers, and others who contributed to the development of science)

have had widely different places in society, and the social norms, ethical values, and epistemic virtues

associated with scientists—and expected of them—have changed over time

as well. Accordingly, many different historical figures can be

identified as early scientists, depending on which characteristics of

modern science are taken to be essential.

Some historians point to the Scientific Revolution

that began in 16th century as the period when science in a recognizably

modern form developed. It wasn't until the 19th century that sufficient

socioeconomic changes occurred for scientists to emerge as a major

profession.

Classical antiquity

Knowledge about nature in classical antiquity was pursued by many kinds of scholars. Greek

contributions to science—including works of geometry and mathematical

astronomy, early accounts of biological processes and catalogs of plants

and animals, and theories of knowledge and learning—were produced by philosophers and physicians, as well as practitioners of various trades. These roles, and their associations with scientific knowledge, spread with the Roman Empire and, with the spread of Christianity, became closely linked to religious institutions in most of European countries. Astrology and astronomy

became an important area of knowledge, and the role of

astronomer/astrologer developed with the support of political and

religious patronage. By the time of the medieval university system, knowledge was divided into the trivium—philosophy, including natural philosophy—and the quadrivium—mathematics,

including astronomy. Hence, the medieval analogs of scientists were

often either philosophers or mathematicians. Knowledge of plants and

animals was broadly the province of physicians.

Middle Ages

Science in medieval Islam

generated some new modes of developing natural knowledge, although

still within the bounds of existing social roles such as philosopher and

mathematician. Many proto-scientists from the Islamic Golden Age are considered polymaths, in part because of the lack of anything corresponding to modern scientific disciplines. Many of these early polymaths were also religious priests and theologians: for example, Alhazen and al-Biruni were mutakallimiin; the physician Avicenna was a hafiz; the physician Ibn al-Nafis was a hafiz, muhaddith and ulema; the botanist Otto Brunfels was a theologian and historian of Protestantism; the astronomer and physician Nicolaus Copernicus was a priest. During the Italian Renaissance scientists like Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Galileo Galilei and Gerolamo Cardano have been considered as the most recognizable polymaths.

Renaissance

During the Renaissance, Italians made substantial contributions in science. Leonardo Da Vinci made significant discoveries in paleontology and anatomy. The Father of modern Science,

Galileo Galilei, made key improvements on the thermometer and telescope which allowed him to observe and clearly describe the solar system. Descartes was not only a pioneer of analytic geometry but formulated a theory of mechanics and advanced ideas about the origins of animal movement and perception. Vision interested the physicists Young and Helmholtz, who also studied optics, hearing and music. Newton extended Descartes' mathematics by inventing calculus (contemporaneously with Leibniz). He provided a comprehensive formulation of classical mechanics and investigated light and optics. Fourier founded a new branch of mathematics — infinite, periodic series — studied heat flow and infrared radiation, and discovered the greenhouse effect. Girolamo Cardano, Blaise Pascal Pierre de Fermat, Von Neumann, Turing, Khinchin, Markov and Wiener, all mathematicians, made major contributions to science and probability theory, including the ideas behind computers, and some of the foundations of statistical mechanics and quantum mechanics. Many mathematically inclined scientists, including Galileo, were also musicians.

There are many compelling stories in medicine and biology, such as the development of ideas about the circulation of blood from Galen to Harvey.

Age of Enlightenment

During the age of Enlightenment, Luigi Galvani, the pioneer of the bioelectromagnetics,

discovered the animal electricity. He discovered that a charge applied

to the spinal cord of a frog could generate muscular spasms throughout

its body. Charges could make frog legs jump even if the legs were no

longer attached to a frog. While cutting a frog leg, Galvani's steel

scalpel touched a brass hook that was holding the leg in place. The leg

twitched. Further experiments confirmed this effect, and Galvani was

convinced that he was seeing the effects of what he called animal

electricity, the life force within the muscles of the frog. At the

University of Pavia, Galvani's colleague Alessandro Volta was able to reproduce the results, but was sceptical of Galvani's explanation.

Lazzaro Spallanzani

is one of the most influential figures in experimental physiology and

the natural sciences. His investigations have exerted a lasting

influence on the medical sciences. He made important contributions to

the experimental study of bodily functions and animal reproduction.

19th century

Until the late 19th or early 20th century, scientists were still referred to as "natural philosophers" or "men of science".

English philosopher and historian of science William Whewell coined the term scientist in 1833, and it first appeared in print in Whewell's anonymous 1834 review of Mary Somerville's On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences published in the Quarterly Review.

Whewell's suggestion of the term was partly satirical, a response to

changing conceptions of science itself in which natural knowledge was

increasingly seen as distinct from other forms of knowledge. Whewell

wrote of "an increasing proclivity of separation and dismemberment" in

the sciences; while highly specific terms proliferated—chemist,

mathematician, naturalist—the broad term "philosopher" was no longer

satisfactory to group together those who pursued science, without the

caveats of "natural" or "experimental" philosopher. Members of the British Association for the Advancement of Science

had been complaining about the lack of a good term at recent meetings,

Whewell reported in his review; alluding to himself, he noted that "some

ingenious gentleman proposed that, by analogy with artist, they might form [the word] scientist, and added that there could be no scruple in making free with this term since we already have such words as economist, and atheist—but this was not generally palatable".

Whewell proposed the word again more seriously (and not anonymously) in his 1840 "The Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences:

As we cannot use physician for a cultivator of physics, I have called him a physicist. We need very much a name to describe a cultivator of science in general. I should incline to call him a Scientist. Thus we might say, that as an Artist is a Musician, Painter, or Poet, a Scientist is a Mathematician, Physicist, or Naturalist.

He also proposed the term physicist at the same time, as a counterpart to the French word physicien. Neither term gained wide acceptance until decades later; scientist became a common term in the late 19th century in the United States and around the turn of the 20th century in Great Britain.

By the twentieth century, the modern notion of science as a special

brand of information about the world, practiced by a distinct group and

pursued through a unique method, was essentially in place.

20th century

Marie Curie

became the first female to win the Nobel Prize and the first person to

win it twice. Her efforts led to the development of nuclear energy and

Radio therapy for the treatment of cancer. In 1922, she was appointed a

member of the International Commission on Intellectual Co-operation by

the Council of the League of Nations. She campaigned for scientist's

right to patent their discoveries and inventions. She also campaigned

for free access to international scientific literature and for

internationally recognized scientific symbols.

Education

In modern times, many professional scientists are trained in an academic setting (e.g., universities and research institutes), mostly at the level of graduate schools. Upon completion, they would normally attain an academic degree, with the highest degree being a doctorate such as a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Doctor of Medicine (MD), Doctor of Engineering (DEng), or even a dual doctoral degree (e.g., MD, PhD). Although graduate education for scientists varies among institutions and countries, some common training requirements include specializing in an area of interest, publishing research findings in peer-reviewed scientific journals and presenting them at scientific conferences, giving lectures or teaching, and defending a thesis (or dissertation) during an oral examination. To aid them in this endeavor, graduate students often work under the guidance of a mentor, usually a senior scientist, which may continue after the completion of their doctorates whereby they work as postdoctoral researchers.

Career

After the completion of their training, many scientists pursue careers in a variety of work settings and conditions. In 2017, the British scientific journal Nature published the results of a large-scale survey of more than 5,700 doctoral students worldwide, asking them which sectors of the economy

that would like to work in. A little over half of the respondents

wanted to pursue a career in academia, with smaller proportions hoping

to work in industry, government, and nonprofit environments.

Scientists are motivated to work in several ways. Many have a desire to understand why the world is as we see it and how it came to be. They exhibit a strong curiosity about reality. Other motivations are recognition by their peers and prestige. The Nobel Prize, a widely regarded prestigious award, is awarded annually to those who have achieved scientific advances in the fields of medicine, physics, chemistry, and economics.

Some scientists have a desire to apply scientific knowledge for the

benefit of people's health, the nations, the world, nature, or

industries (academic scientist and industrial scientist).

Scientists tend to be less motivated by direct financial reward for

their work than other careers. As a result, scientific researchers often

accept lower average salaries when compared with many other professions

which require a similar amount of training and qualification.

Research interests

Scientists include experimentalists who mainly perform experiments to test hypotheses, and theoreticians who mainly develop models

to explain existing data and predict new results. There is a continuum

between two activities and the division between them is not clear-cut,

with many scientists performing both tasks.

Those considering science as a career often look to the frontiers. These include cosmology and biology, especially molecular biology and the human genome project. Other areas of active research include the exploration of matter at the scale of elementary particles as described by high-energy physics, and materials science, which seeks to discover and design new materials. Although there have been remarkable discoveries with regard to brain function and neurotransmitters, the nature of the mind and human thought still remains unknown.

By specialization

Natural science

Physical science

Life science

Social science

Formal science

Applied

Interdisciplinary

By employer

Demography

By country

The

number of scientists is vastly different from country to country. For

instance, there are only four full-time scientists per 10,000 workers in

India while this number is 79 for the United Kingdom and the United States.

|

|

United States

According to the United States National Science Foundation

4.7 million people with science degrees worked in the United States in

2015, across all disciplines and employment sectors. The figure included

twice as many men as women. Of that total, 17% worked in academia, that

is, at universities and undergraduate institutions, and men held 53% of

those positions. 5% of scientists worked for the federal government and

about 3.5% were self-employed. Of the latter two groups, two-thirds

were men. 59% of US scientists were employed in industry or business,

and another 6% worked in non-profit positions.

By gender

Scientist and engineering statistics are usually intertwined, but

they indicate that women enter the field far less than men, though this

gap is narrowing. The number of science and engineering doctorates

awarded to women rose from a mere 7 percent in 1970 to 34 percent in

1985 and in engineering alone the numbers of bachelor's degrees awarded

to women rose from only 385 in 1975 to more than 11000 in 1985.