Philosophers of law ask "what is law, and what should it be?"

Jurisprudence or legal theory is the theoretical study of law, principally by philosophers but, from the twentieth century, also by social scientists. Scholars of jurisprudence, also known as jurists or legal theorists, hope to obtain a deeper understanding of legal reasoning, legal systems, legal institutions, and the role of law in society.

Modern jurisprudence began in the 18th century and was focused on the first principles of natural law, civil law, and the law of nations.

General jurisprudence can be divided into categories both by the type

of question scholars seek to answer and by the theories of

jurisprudence, or schools of thought, regarding how those questions are

best answered. Contemporary philosophy of law, which deals with general

jurisprudence, addresses problems internal to law and legal systems and

problems of law as a social institution that relates to the larger

political and social context in which it exists.

This article addresses three distinct branches of thought in general jurisprudence. Ancient natural law

is the idea that there are rational objective limits to the power of

legislative rulers. The foundations of law are accessible through

reason, and it is from these laws of nature that human laws gain

whatever force they have. Analytic jurisprudence rejects natural law's fusing of what law

is and what it ought to be. It espouses the use of a neutral point of

view and descriptive language when referring to aspects of legal

systems.

It encompasses such theories of jurisprudence as "legal positivism",

which holds that there is no necessary connection between law and

morality and that the force of law comes from basic social facts;

and "legal realism", which argues that the real-world practice of law

determines what law is, the law having the force that it does because of

what legislators, lawyers, and judges do with it. Normative jurisprudence

is concerned with "evaluative" theories of law. It deals with what the

goal or purpose of law is, or what moral or political theories provide a

foundation for the law. It not only addresses the question "What is

law?", but also tries to determine what the proper function of law

should be, or what sorts of acts should be subject to legal sanctions,

and what sorts of punishment should be permitted.

Etymology

The English word is derived from the Latin maxim jurisprudentia. Juris is the genitive form of jus meaning law, and prudentia

means prudence (also: discretion, foresight, forethought,

circumspection. It refers to the exercise of good judgment, common

sense, and caution, especially in the conduct of practical matters. The

word first appeared in written English in 1628, at a time when the word prudence meant knowledge of, or skill in, a matter. It may have entered English via the French jurisprudence, which appeared earlier.

History

Ancient Indian jurisprudence is mentioned in various Dharmaśāstra texts, starting with the Dharmasutra of Bhodhayana.

Jurisprudence in Ancient Rome had its origins with the (periti)—experts in the jus mos maiorum (traditional law), a body of oral laws and customs.

Praetors established a working body of laws by judging whether or

not singular cases were capable of being prosecuted either by the

edicta, the annual pronunciation of prosecutable offense, or in

extraordinary situations, additions made to the edicta. An iudex would

then prescribe a remedy according to the facts of the case.

The sentences of the iudex were supposed to be simple

interpretations of the traditional customs, but—apart from considering

what traditional customs applied in each case—soon developed a more

equitable interpretation, coherently adapting the law to newer social

exigencies. The law was then adjusted with evolving institutiones (legal concepts), while remaining in the traditional mode. Praetors were replaced in the 3rd century BC by a laical body of prudentes. Admission to this body was conditional upon proof of competence or experience.

Under the Roman Empire,

schools of law were created, and practice of the law became more

academic. From the early Roman Empire to the 3rd century, a relevant

body of literature was produced by groups of scholars, including the

Proculians and Sabinians. The scientific nature of the studies was unprecedented in ancient times.

After the 3rd century, juris prudentia became a more bureaucratic activity, with few notable authors. It was during the Eastern Roman Empire (5th century) that legal studies were once again undertaken in depth, and it is from this cultural movement that Justinian's Corpus Juris Civilis was born.

Natural law

In

its general sense, natural law theory may be compared to both

state-of-nature law and general law understood on the basis of being

analogous to the laws of physical science. Natural law is often

contrasted to positive law which asserts law as the product of human

activity and human volition.

Another approach to natural-law jurisprudence generally asserts

that human law must be in response to compelling reasons for action.

There are two readings of the natural-law jurisprudential stance.

- The Strong Natural Law Thesis holds that if a human law fails to be in response to compelling reasons, then it is not properly a "law" at all. This is captured, imperfectly, in the famous maxim: lex iniusta non est lex (an unjust law is no law at all).

- The Weak Natural Law Thesis holds that if a human law fails to be in response to compelling reasons, then it can still be called a "law", but it must be recognized as a defective law.

Notions of an objective moral order, external to human legal systems,

underlie natural law. What is right or wrong can vary according to the

interests one is focused on. John Finnis, the most important of modern natural barristers, has argued that the maxim "an unjust law is no law at all" is a poor guide to the classical Thomist position. Strongly related to theories of natural law are classical theories of justice, beginning in the West with Plato's Republic.

Aristotle

Aristotle is often said to be the father of natural law. Like his philosophical forefathers Socrates and Plato, Aristotle posited the existence of natural justice or natural right (dikaion physikon, δικαίον φυσικόν, Latin ius naturale). His association with natural law is largely due to how he was interpreted by Thomas Aquinas. This was based on Aquinas' conflation of natural law and natural right, the latter of which Aristotle posits in Book V of the Nicomachean Ethics (= Book IV of the Eudemian Ethics). Aquinas's influence was such as to affect a number of early translations of these passages, though more recent translations render them more literally.

Aristotle's theory of justice is bound up in his idea of the golden mean.

Indeed, his treatment of what he calls "political justice" derives from

his discussion of "the just" as a moral virtue derived as the mean

between opposing vices, just like every other virtue he describes. His longest discussion of his theory of justice occurs in Nicomachean Ethics

and begins by asking what sort of mean a just act is. He argues that

the term "justice" actually refers to two different but related ideas:

general justice and particular justice.

When a person's actions toward others are completely virtuous in all

matters, Aristotle calls them "just" in the sense of "general justice";

as such, this idea of justice is more or less coextensive with virtue.

"Particular" or "partial justice", by contrast, is the part of "general

justice" or the individual virtue that is concerned with treating

others equitably.

Aristotle moves from this unqualified discussion of justice to a

qualified view of political justice, by which he means something close

to the subject of modern jurisprudence. Of political justice, Aristotle

argues that it is partly derived from nature and partly a matter of

convention.

This can be taken as a statement that is similar to the views of modern

natural law theorists. But it must also be remembered that Aristotle is

describing a view of morality, not a system of law, and therefore his

remarks as to nature are about the grounding of the morality enacted as

law, not the laws themselves.

The best evidence of Aristotle's having thought there was a natural law comes from the Rhetoric,

where Aristotle notes that, aside from the "particular" laws that each

people has set up for itself, there is a "common" law that is according

to nature.

The context of this remark, however, suggests only that Aristotle

thought that it could be rhetorically advantageous to appeal to such a

law, especially when the "particular" law of one's own city was adverse

to the case being made, not that there actually was such a law. Aristotle, moreover, considered certain candidates for a universally valid, natural law to be wrong. Aristotle's theoretical paternity of the natural law tradition is consequently disputed.

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas was the most influential Western medieval legal scholar

Thomas Aquinas (Thomas of Aquin, or Aquino, c. 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian philosopher and theologian in the scholastic tradition, known as "Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Universalis". He is the foremost classical proponent of natural theology, and the father of the Thomistic school of philosophy, for a long time the primary philosophical approach of the Roman Catholic Church. The work for which he is best known is the Summa Theologica. One of the thirty-five Doctors of the Church, he is considered by many Catholics to be the Church's greatest theologian. Consequently, many institutions of learning have been named after him.

Aquinas distinguished four kinds of law: eternal, natural, divine, and human:

- Eternal law refers to divine reason, known only to God. It is God's plan for the universe. Man needs this plan, for without it he would totally lack direction.

- Natural law is the "participation" in the eternal law by rational human creatures, and is discovered by reason.

- Divine law is revealed in the scriptures and is God's positive law for mankind.

- Human law is supported by reason and enacted for the common good.

Natural law, of course, is based on "first principles":

... this is the first precept of the law, that good is to be done and promoted, and evil is to be avoided. All other precepts of the natural law are based on this ...

The desires to live and to procreate are counted by Aquinas among

those basic (natural) human values on which all other human values are

based.

School of Salamanca

Francisco de Vitoria was perhaps the first to develop a theory of ius gentium

(the rights of peoples), and thus is an important figure in the

transition to modernity. He extrapolated his ideas of legitimate

sovereign power to international affairs, concluding that such affairs

ought to be determined by forms respecting of the rights of all and that

the common good of the world should take precedence before the good of

any single state. This meant that relations between states ought to pass

from being justified by force to being justified by law and justice.

Some scholars have upset the standard account of the origins of

International law, which emphasizes the seminal text De iure belli ac pacis by Grotius, and argued for Vitoria and, later, Suárez's importance as forerunners and, potentially, founders of the field.

Others, such as Koskenniemi, have argued that none of these humanist

and scholastic thinkers can be understood to have founded international

law in the modern sense, instead placing its origins in the post-1870

period.

Francisco Suárez, regarded as among the greatest scholastics after Aquinas, subdivided the concept of ius gentium. Working with already well-formed categories, he carefully distinguished ius inter gentes from ius intra gentes. Ius inter gentes

(which corresponds to modern international law) was something common to

the majority of countries, although, being positive law, not natural

law, it was not necessarily universal. On the other hand, ius intra gentes, or civil law, is specific to each nation.

Thomas Hobbes

In his treatise, Leviathan (1651), Hobbes expresses a view of natural law as a precept—or general rule, founded on reason—by

which a man is forbidden to do that which is destructive to his life,

to take away the means of preserving the same, or to omit that by which

he thinks it may best be preserved. Hobbes was a social contractarian and believed that the law had peoples' tacit consent. He believed that society was formed from a state of nature

to protect people from the state of war that would exist otherwise.

According to Hobbes, without an ordered society, life is, "solitary,

poor, nasty, brutish and short". It is commonly said that Hobbes's views

on human nature were influenced by his times. The English Civil War

and the Cromwellian dictatorship had taken place; and, in reacting to

that, Hobbes felt that absolute authority vested in a monarch, whose

subjects obeyed the law, was the basis of a civilized society.

Lon Fuller

Writing after World War II,

Lon L. Fuller defended a secular and procedural form of natural law. He

emphasised that the (natural) law must meet certain formal requirements

(such as being impartial and publicly knowable). To the extent that an

institutional system of social control falls short of these

requirements, Fuller argued, we are less inclined to recognize it as a

system of law, or to give it our respect. Thus, the law must have a

morality that goes beyond the societal rules under which laws are made.

John Finnis

Sophisticated positivist and natural law theories sometimes resemble

each other and may have certain points in common. Identifying a

particular theorist as a positivist or a natural law theorist sometimes

involves matters of emphasis and degree, and the particular influences

on the theorist's work. The natural law theorists of the distant past,

such as Aquinas and John Locke made no distinction between analytic and

normative jurisprudence, while modern natural law theorists, such as

John Finnis, who claim to be positivists, still argue that law is moral

by nature. In his book Natural Law and Natural Rights (1980, 2011), John Finnis provides a restatement of natural law doctrine.

Analytic jurisprudence

Analytic, or "clarificatory", jurisprudence means taking a neutral

point of view and using descriptive language when referring to various

aspects of legal systems. This was a philosophical development that

rejected natural law's fusing of what law is and what it ought to be. David Hume argued, in A Treatise of Human Nature, that people invariably slip from describing what the world is to asserting that we therefore ought to follow a particular course of action. But as a matter of pure logic, one cannot conclude that we ought to do something merely because something is the case. So analysing and clarifying the way the world is must be treated as a strictly separate question from normative and evaluative questions pf what ought to be done.

The most important questions of analytic jurisprudence are: "What are laws?"; "What is the

law?"; "What is the relationship between law and power/sociology?"; and

"What is the relationship between law and morality?" Legal positivism

is the dominant theory, although there is a growing number of critics

who offer their own interpretations.

Historical school

Historical jurisprudence came to prominence during the debate on the proposed codification of German law. In his book On the Vocation of Our Age for Legislation and Jurisprudence, Friedrich Carl von Savigny

argued that Germany did not have a legal language that would support

codification because the traditions, customs, and beliefs of the German

people did not include a belief in a code. Historicists believe that law

originates with society.

Sociological jurisprudence

An effort to systematically to inform jurisprudence from sociological

insights developed from the beginning of the twentieth century, as

sociology began to establish itself as a distinct social science,

especially in the United States and in continental Europe. In Germany,

the work of the "free law" theorists (e.g. Ernst Fuchs, Hermann Kantorowicz, and Eugen Ehrlich)

encouraged the use of sociological insights in the development of legal

and juristic theory. The most internationally influential advocacy for a

"sociological jurisprudence" occurred in the United States, where,

throughout the first half of the twentieth century, Roscoe Pound,

for many years the Dean of Harvard Law School, used this term to

characterise his legal philosophy. In the United States, many later

writers followed Pound's lead or developed distinctive approaches to

sociological jurisprudence. In Australia, Julius Stone

strongly defended and developed Pound's ideas. In the 1930s, a

significant split between the sociological jurists and the American

legal realists emerged. In the second half of the twentieth century,

sociological jurisprudence as a distinct movement declined as

jurisprudence came more strongly under the influence of analytical legal

philosophy; but with increasing criticism of dominant orientations of

legal philosophy in English-speaking countries in the present century,

it has attracted renewed interest.

Legal positivism

Positivism simply means that law is something that is "posited": laws

are validly made in accordance with socially accepted rules. The

positivist view of law can be seen to be based on two broad principles:

- Firstly, that laws may seek to enforce justice, morality, or any other normative end, but their success or failure to do so does not determine their validity. Provided a law is properly formed, in accordance with the rules recognized in the society concerned, it is a valid law, regardless of whether it is just by some other standard.

- Secondly, that law is nothing more than a set of rules to provide order and governance of society.

No legal positivist, however, argues that it follows that the law is therefore to be obeyed, no matter what. This is seen as a separate question entirely.

- What the law is (lex lata) - is determined by historical social practice (resulting in rules).

- What the law ought to be (lex ferenda) - is determined by moral considerations.

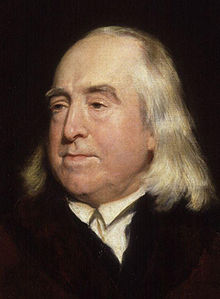

Bentham and Austin

Bentham's utilitarian theories remained dominant in law until the twentieth century

One of the earliest legal positivists was Jeremy Bentham. Along with

Hume, Bentham was an early and staunch supporter of the utilitarian

concept, and was an avid prison reformer, advocate for democracy, and firm atheist. Bentham's views about law and jurisprudence were popularized by his student John Austin. Austin was the first chair of law at the new University of London, from 1829. Austin's utilitarian

answer to "what is law?" was that law is "commands, backed by threat of

sanctions, from a sovereign, to whom people have a habit of obedience".

Contemporary legal positivists, H. L. A. Hart particularly, have long

abandoned this view, and have criticised its oversimplification.

Hans Kelsen

Hans Kelsen is considered one of the prominent jurists of the 20th

century and has been highly influential in Europe and Latin America,

although less so in common-law countries. His Pure Theory of Law

describes law as "binding norms", while at the same time refusing to

evaluate those norms. That is, "legal science" is to be separated from

"legal politics". Central to the Pure Theory of Law is the notion of a

"basic norm" (Grundnorm)'—a hypothetical norm, presupposed by the jurist, from which all "lower" norms in the hierarchy of a legal system, beginning with constitutional law,

are understood to derive their authority or the extent to which they

are binding. Kelsen contends that the extent to which legal norms are

binding, their specifically "legal" character, can be understood without

tracing it ultimately to some suprahuman source such as God,

personified Nature or—of great importance in his time—a personified

State or Nation.

H. L. A. Hart

In the English-speaking world, the pivotal writer was H. L. A. Hart, professor of jurisprudence at Oxford University,

who argued that the law should be understood as a system of social

rules. Hart rejected Kelsen's views that sanctions were essential to law

and that a normative social phenomenon, like law, cannot be grounded in

non-normative social facts. Hart revived analytical jurisprudence as an

important theoretical debate in the twentieth century, through his book

The Concept of Law.

Rules, said Hart, are divided into primary rules (rules of

conduct) and secondary rules (rules addressed to officials who

administer primary rules). Secondary rules are divided into rules of

adjudication (how to resolve legal disputes), rules of change (how laws

are amended), and the rule of recognition (how laws are identified as

valid). The "rule of recognition" is a customary practice of officials

(especially barristers and judges) who identify certain acts and

decisions as sources of law. In 1981, Neil MacCormick

wrote a pivotal book on Hart (second edition published in 2008), which

further refined and offered some important criticisms that led

MacCormick to develop his own theory (the best example of which is his Institutions of Law, 2007). Other important critiques include those of Ronald Dworkin, John Finnis, and Joseph Raz.

In recent years, debates on the nature of law have become

increasingly fine-grained. One important debate is within legal

positivism. One school is sometimes called "exclusive legal positivism"

and is associated with the view that the legal validity of a norm can

never depend on its moral correctness. A second school is labeled

"inclusive legal positivism", a major proponent of which is Wil

Waluchow, and is associated with the view that moral considerations may, but do not necessarily, determine the legal validity of a norm.

Joseph Raz

Some philosophers used to contend that positivism was the theory that

held that there was "no necessary connection" between law and morality;

but influential contemporary positivists—including Joseph Raz, John

Gardner, and Leslie Green—reject that view. As Raz points out, it is a

necessary truth that there are vices that a legal system cannot possibly

have (for example, it cannot commit rape or murder).

Joseph Raz defends the positivist outlook, but criticized Hart's "soft social thesis" approach in The Authority of Law.

Raz argues that law is authority, identifiable purely through social

sources, without reference to moral reasoning. Any categorization of

rules beyond their role as authority is better left to sociology than to

jurisprudence.

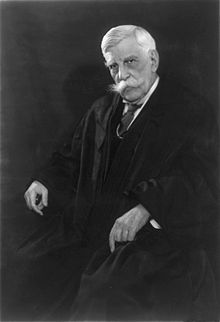

Legal realism

Oliver Wendell Holmes was a self-styled legal realist

Legal realism was a view popular with some Scandinavian and American

writers. Skeptical in tone, it held that the law should be understood

as, and would be determined by, the actual practices of courts, law

offices, and police stations, rather than as the rules and doctrines set

forth in statutes or learned treatises. Legal realism had some

affinities with the sociology of law and sociological jurisprudence. The

essential tenet of legal realism is that all law is made by human

beings and, thus, is subject to human foibles, frailties, and

imperfections.

It has become common today to identify Justice Oliver Wendell

Holmes, Jr., as the main precursor of American Legal Realism (other

influences include Roscoe Pound, Karl Llewellyn, and Justice Benjamin Cardozo).

Karl Llewellyn, another founder of the U.S. legal realism movement,

similarly believed that the law is little more than putty in the hands

of judges who are able to shape the outcome of cases based on their

personal values or policy choices. Many consider the chief inspiration for Scandinavian legal realism to be the works of Axel Hägerström.

Despite its decline in popularity, legal realism continues to

influence a wide spectrum of jurisprudential schools today, including critical legal studies, feminist legal theory, critical race theory, sociology of law, and law and economics.

Critical legal studies

Critical legal studies

are a new theory of jurisprudence that has developed since the 1970s.

The theory can generally be traced to American legal realism and is

considered "the first movement in legal theory and legal scholarship in

the United States to have espoused a committed Left political stance and

perspective".

It holds that the law is largely contradictory, and can be best

analyzed as an expression of the policy goals of a dominant social

group.

Critical rationalism

Karl Popper originated the theory of critical rationalism. According to Reinhold Zippelius

many advances in law and jurisprudence take place by operations of

critical rationalism. He writes

"daß die Suche nach dem Begriff des Rechts, nach seinen Bezügen zur Wirklichkeit und nach der Gerechtigkeit experimentierend voranschreitet, indem wir Problemlösungen versuchsweise entwerfen, überprüfen und verbessern" (that we empirically search for solutions to problems, which harmonize fairly with reality, by projecting, testing and improving the solutions).

Legal interpretivism

Contemporary philosopher of law Ronald Dworkin

has advocated a more constructivist theory of jurisprudence that can be

characterized as a middle path between natural law theories and

positivist theories of general jurisprudence.

In his book Law's Empire, Dworkin attacked Hart

and the positivists for their refusal to treat law as a moral issue. He

argued that law is an "interpretive" concept that requires barristers

to find the best-fitting and most just solution to a legal dispute,

given their constitutional traditions. According to him, law is not

entirely based on social facts, but includes the best moral

justification for the institutional facts and practices that we

intuitively regard as legal. It follows from Dworkin's view that one

cannot know whether a society has a legal system in force, or what any

of its laws are, until one knows some truths about the moral

justifications of the social and political practices of that society. It

is consistent with Dworkin's view—in contrast with the views of legal

positivists or legal realists—that no-one in a society may know what its laws are, because no-one may know the best moral justification for its practices.

Interpretation, according to Dworkin's "integrity theory of law",

has two dimensions. To count as an interpretation, the reading of a

text must meet the criterion of "fit". Of those interpretations that

fit, however, Dworkin maintains that the correct interpretation is the

one that portrays the practices of the community in their best light, or

makes them "the best that they can be". But many writers have doubted

whether there is a single best moral justification for the

complex practices of any given community, and others have doubted

whether, even if there is, it should be counted as part of the law of

that community.

Therapeutic jurisprudence

Consequences of the operation of legal rules or legal procedures—or

of the behavior of legal actors (such as lawyers and judges)—may be

either beneficial (therapeutic) or harmful (anti-therapeutic) to people.

Therapeutic jurisprudence ("TJ") studies law as a social force (or agent) and uses social science

methods and data to study the extent to which a legal rule or practice

affects the psychological well-being of the people it impacts.

Normative jurisprudence

In addition to the question, "What is law?", legal philosophy is also

concerned with normative, or "evaluative" theories of law. What is the

goal or purpose of law? What moral or political theories provide a

foundation for the law? What is the proper function of law? What sorts

of acts should be subject to punishment,

and what sorts of punishment should be permitted? What is justice? What

rights do we have? Is there a duty to obey the law? What value has the

rule of law? Some of the different schools and leading thinkers are

discussed below.

Virtue jurisprudence

Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), a detail of The School of Athens

Aretaic moral theories, such as contemporary virtue ethics,

emphasize the role of character in morality. Virtue jurisprudence is

the view that the laws should promote the development of virtuous

character in citizens. Historically, this approach has been mainly

associated with Aristotle or Thomas Aquinas. Contemporary virtue

jurisprudence is inspired by philosophical work on virtue ethics.

Deontology

Deontology is the "theory of duty or moral obligation". The philosopher Immanuel Kant

formulated one influential deontological theory of law. He argued that

any rule we follow must be able to be universally applied, i.e. we must

be willing for everyone to follow that rule. A contemporary

deontological approach can be found in the work of the legal philosopher

Ronald Dworkin.

Utilitarianism

Mill believed law should create happiness

Utilitarianism is the view that the laws should be crafted so as to

produce the best consequences for the greatest number of people.

Historically, utilitarian thinking about law has been associated with

the philosopher Jeremy Bentham. John Stuart Mill was a pupil of

Bentham's and was the torch bearer for utilitarian philosophy throughout the late nineteenth century.

In contemporary legal theory, the utilitarian approach is frequently

championed by scholars who work in the law and economics tradition.

John Rawls

John Rawls was an American philosopher; a professor of political philosophy at Harvard University; and author of A Theory of Justice (1971), Political Liberalism, Justice as Fairness: A Restatement, and The Law of Peoples.

He is widely considered one of the most important English-language

political philosophers of the 20th century. His theory of justice uses a

method called "original position" to ask us which principles of justice

we would choose to regulate the basic institutions of our society if we

were behind a "veil of ignorance". Imagine we do not know who we

are—our race, sex, wealth, status, class, or any distinguishing

feature—so that we would not be biased in our own favour. Rawls argued

from this "original position" that we would choose exactly the same

political liberties for everyone, like freedom of speech, the right to

vote, and so on. Also, we would choose a system where there is only

inequality because that produces incentives enough for the economic

well-being of all society, especially the poorest. This is Rawls's

famous "difference principle". Justice is fairness, in the sense that

the fairness of the original position of choice guarantees the fairness

of the principles chosen in that position.

There are many other normative approaches to the philosophy of law, including critical legal studies and libertarian theories of law.