Structural functionalism, or simply functionalism, is "a framework for building theory that sees society as a complex system whose parts work together to promote solidarity and stability". This approach looks at society through a macro-level orientation, which is a broad focus on the social structures that shape society as a whole, and believes that society has evolved like organisms. This approach looks at both social structure and social functions. Functionalism addresses society as a whole in terms of the function of its constituent elements; namely norms, customs, traditions, and institutions.

A common analogy, popularized by Herbert Spencer, presents these parts of society as "organs" that work toward the proper functioning of the "body" as a whole. In the most basic terms, it simply emphasizes "the effort to impute, as rigorously as possible, to each feature, custom, or practice, its effect on the functioning of a supposedly stable, cohesive system". For Talcott Parsons, "structural-functionalism" came to describe a particular stage in the methodological development of social science, rather than a specific school of thought.

A common analogy, popularized by Herbert Spencer, presents these parts of society as "organs" that work toward the proper functioning of the "body" as a whole. In the most basic terms, it simply emphasizes "the effort to impute, as rigorously as possible, to each feature, custom, or practice, its effect on the functioning of a supposedly stable, cohesive system". For Talcott Parsons, "structural-functionalism" came to describe a particular stage in the methodological development of social science, rather than a specific school of thought.

Theory

Classical theories are defined by a tendency towards biological analogy and notions of social evolution:

Functionalist thought, from Comte onwards, has looked particularly towards biology as the science providing the closest and most compatible model for social science. Biology has been taken to provide a guide to conceptualizing the structure and the function of social systems and to analyzing processes of evolution via mechanisms of adaptation ... functionalism strongly emphasises the pre-eminence of the social world over its individual parts (i.e. its constituent actors, human subjects).

— Anthony Giddens, The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration

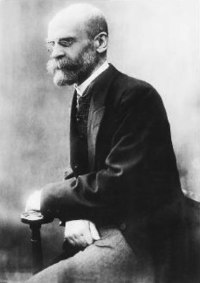

Émile Durkheim

While one may regard functionalism as a logical extension of the organic analogies for societies presented by political philosophers such as Rousseau, sociology draws firmer attention to those institutions unique to industrialized capitalist society. Functionalism also has an anthropological basis in the work of theorists such as Marcel Mauss, Bronisław Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown. It is in Radcliffe-Brown's specific usage that the prefix 'structural' emerged.

Radcliffe-Brown proposed that most stateless, "primitive" societies,

lacking strong centralized institutions, are based on an association of

corporate-descent groups. Structural functionalism also took on Malinowski's argument that the basic building block of society is the nuclear family, and that the clan is an outgrowth, not vice versa.

Émile Durkheim

was concerned with the question of how certain societies maintain

internal stability and survive over time. He proposed that such

societies tend to be segmented, with equivalent parts held together by

shared values, common symbols or, as his nephew Marcel Mauss held,

systems of exchanges. Durkheim used the term mechanical solidarity

to refer to these types of "social bonds, based on common sentiments

and shared moral values, that are strong among members of pre-industrial

societies".

In modern, complex societies, members perform very different tasks,

resulting in a strong interdependence. Based on the metaphor above of an

organism in which many parts function together to sustain the whole,

Durkheim argued that complex societies are held together by organic solidarity, i.e. "social bonds, based on specialization and interdependence, that are strong among members of industrial societies".

These views were upheld by Durkheim, who, following Auguste Comte,

believed that society constitutes a separate "level" of reality,

distinct from both biological and inorganic matter. Explanations of social phenomena

had therefore to be constructed within this level, individuals being

merely transient occupants of comparatively stable social roles. The

central concern of structural functionalism is a continuation of the

Durkheimian task of explaining the apparent stability and internal cohesion

needed by societies to endure over time. Societies are seen as

coherent, bounded and fundamentally relational constructs that function

like organisms, with their various (or social institutions) working

together in an unconscious, quasi-automatic fashion toward achieving an

overall social equilibrium.

All social and cultural phenomena are therefore seen as functional in

the sense of working together, and are effectively deemed to have

"lives" of their own. They are primarily analyzed in terms of this

function. The individual is significant not in and of himself, but

rather in terms of his status, his position in patterns of social

relations, and the behaviors associated with his status. Therefore, the

social structure is the network of statuses connected by associated

roles.

It is simplistic to equate the perspective directly with political conservatism. The tendency to emphasize "cohesive systems", however, leads functionalist theories to be contrasted with "conflict theories" which instead emphasize social problems and inequalities.

Prominent theorists

Auguste Comte

Auguste Comte, the "Father of Positivism",

pointed out the need to keep society unified as many traditions were

diminishing. He was the first person to coin the term sociology. Comte

suggests that sociology is the product of a three-stage development:

- Theological stage: From the beginning of human history until the end of the European Middle Ages, people took a religious view that society expressed God's will. In the theological state, the human mind, seeking the essential nature of beings, the first and final causes (the origin and purpose) of all effects—in short, absolute knowledge—supposes all phenomena to be produced by the immediate action of supernatural beings.

- Metaphysical stage: People began seeing society as a natural system as opposed to the supernatural. This began with enlightenment and the ideas of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau. Perceptions of society reflected the failings of a selfish human nature rather than the perfection of God.

- Positive or scientific stage: Describing society through the application of the scientific approach, which draws on the work of scientists.

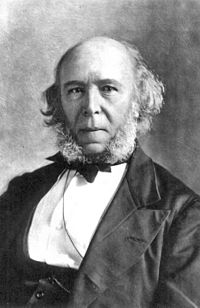

Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) was a British philosopher famous for applying the theory of natural selection to society. He was in many ways the first true sociological functionalist.

In fact, while Durkheim is widely considered the most important

functionalist among positivist theorists, it is known that much of his

analysis was culled from reading Spencer's work, especially his Principles of Sociology (1874–96).

In describing society, Spencer alludes to the analogy of a human body.

Just as the structural parts of the human body — the skeleton, muscles,

and various internal organs — function independently to help the entire

organism survive, social structures work together to preserve society.

While reading Spencer's massive volumes can be tedious (long passages explicating the organic analogy, with reference to cells,

simple organisms, animals, humans and society), there are some

important insights that have quietly influenced many contemporary

theorists, including Talcott Parsons, in his early work The Structure of Social Action (1937). Cultural anthropology also consistently uses functionalism.

This evolutionary model, unlike most 19th century evolutionary theories, is cyclical, beginning with the differentiation and increasing complication of an organic or "super-organic" (Spencer's term for a social system) body, followed by a fluctuating state of equilibrium and disequilibrium (or a state of adjustment and adaptation), and, finally, the stage of disintegration or dissolution. Following Thomas Malthus' population principles, Spencer concluded that society is constantly facing selection pressures (internal and external) that force it to adapt its internal structure through differentiation.

Every solution, however, causes a new set of selection pressures

that threaten society's viability. It should be noted that Spencer was

not a determinist in the sense that he never said that

- Selection pressures will be felt in time to change them;

- They will be felt and reacted to; or

- The solutions will always work.

In fact, he was in many ways a political sociologist,

and recognized that the degree of centralized and consolidated

authority in a given polity could make or break its ability to adapt. In

other words, he saw a general trend towards the centralization of power

as leading to stagnation and ultimately, pressures to decentralize.

More specifically, Spencer recognized three functional needs or

prerequisites that produce selection pressures: they are regulatory,

operative (production) and distributive. He argued that all societies

need to solve problems of control and coordination, production of goods,

services and ideas, and, finally, to find ways of distributing these resources.

Initially, in tribal societies, these three needs are inseparable, and the kinship

system is the dominant structure that satisfies them. As many scholars

have noted, all institutions are subsumed under kinship organization,

but, with increasing population (both in terms of sheer numbers and

density), problems emerge with regard to feeding individuals, creating

new forms of organization—consider the emergent division of

labor—coordinating and controlling various differentiated social units,

and developing systems of resource distribution.

The solution, as Spencer sees it, is to differentiate structures

to fulfill more specialized functions; thus a chief or "big man"

emerges, soon followed by a group of lieutenants, and later kings and

administrators. The structural parts of society (e.g. families, work)

function interdependently to help society function. Therefore, social

structures work together to preserve society.

Perhaps Spencer's greatest obstacle that is being widely discussed in modern sociology is the fact that much of his social philosophy is rooted in the social and historical context of ancient Egypt. He coined the term "survival of the fittest"

in discussing the simple fact that small tribes or societies tend to be

defeated or conquered by larger ones. Of course, many sociologists

still use his ideas (knowingly or otherwise) in their analyses,

especially due to the recent re-emergence of evolutionary theory.

Talcott Parsons

Talcott Parsons

began writing in the 1930s and contributed to sociology, political

science, anthropology, and psychology. Structural functionalism and

Parsons have received a lot of criticism. Numerous critics have pointed

out Parsons' under emphasis of political and monetary struggle, the

basics of social change, and the by and large "manipulative" conduct

unregulated by qualities and standards. Structural functionalism, and a

large portion of Parsons' works, appear to be insufficient in their

definitions concerning the connections among institutionalized and

non-institutionalized conduct, and the procedures by which institutionalization happens.

Parsons was heavily influenced by Durkheim and Max Weber, synthesizing much of their work into his action theory, which he based on the system-theoretical concept and the methodological principle of voluntary action. He held that "the social system is made up of the actions of individuals."

His starting point, accordingly, is the interaction between two

individuals faced with a variety of choices about how they might act, choices that are influenced and constrained by a number of physical and social factors.

Parsons determined that each individual has expectations of the

other's action and reaction to his own behavior, and that these

expectations would (if successful) be "derived" from the accepted norms

and values of the society they inhabit.

As Parsons himself emphasized, in a general context there would never

exist any perfect "fit" between behaviors and norms, so such a relation

is never complete or "perfect".

Social norms were always problematic for Parsons, who never claimed (as has often been alleged)

that social norms were generally accepted and agreed upon, should this

prevent some kind of universal law. Whether social norms were accepted

or not was for Parsons simply a historical question.

As behaviors are repeated in more interactions, and these expectations are entrenched or institutionalized, a role

is created. Parsons defines a "role" as the normatively-regulated

participation "of a person in a concrete process of social interaction

with specific, concrete role-partners."

Although any individual, theoretically, can fulfill any role, the

individual is expected to conform to the norms governing the nature of

the role they fulfill.

Furthermore, one person can and does fulfill many different roles

at the same time. In one sense, an individual can be seen to be a

"composition"

of the roles he inhabits. Certainly, today, when asked to describe

themselves, most people would answer with reference to their societal

roles.

Parsons later developed the idea of roles into a collective of

roles that complement each other in fulfilling functions for society. Some roles are bound up in institutions

and social structures (economic, educational, legal and even

gender-based). These are functional in the sense that they assist

society in operating and fulfilling its functional needs so that society runs smoothly.

Contrary to prevailing myth, Parsons never spoke about a society

where there was no conflict or some kind of "perfect" equilibrium.

A society's cultural value-system was in the typical case never

completely integrated, never static and most of the time, like in the

case of the American society, in a complex state of transformation

relative to its historical point of departure. To reach a "perfect"

equilibrium was not any serious theoretical question in Parsons analysis

of social systems, indeed, the most dynamic societies had generally

cultural systems with important inner tensions like the US and India.

These tensions were a source of their strength according to Parsons

rather than the opposite. Parsons never thought about

system-institutionalization and the level of strains (tensions,

conflict) in the system as opposite forces per se.

The key processes for Parsons for system reproduction are socialization and social control.

Socialization is important because it is the mechanism for transferring

the accepted norms and values of society to the individuals within the

system. Parsons never spoke about "perfect socialization"—in any society

socialization was only partial and "incomplete" from an integral point

of view.

Parsons states that "this point [...] is independent of the sense

in which [the] individual is concretely autonomous or creative rather

than 'passive' or 'conforming', for individuality and creativity, are to

a considerable extent, phenomena of the institutionalization of

expectations"; they are culturally constructed.

Socialization is supported by the positive and negative

sanctioning of role behaviours that do or do not meet these

expectations.

A punishment could be informal, like a snigger or gossip, or more

formalized, through institutions such as prisons and mental homes. If

these two processes were perfect, society would become static and

unchanging, but in reality this is unlikely to occur for long.

Parsons recognizes this, stating that he treats "the structure of the system as problematic and subject to change," and that his concept of the tendency towards equilibrium "does not imply the empirical dominance of stability over change." He does, however, believe that these changes occur in a relatively smooth way.

Individuals in interaction with changing situations adapt through a process of "role bargaining".

Once the roles are established, they create norms that guide further

action and are thus institutionalized, creating stability across social

interactions. Where the adaptation process cannot adjust, due to sharp

shocks or immediate radical change, structural dissolution occurs and

either new structures (or therefore a new system) are formed, or society

dies. This model of social change has been described as a "moving equilibrium", and emphasizes a desire for social order.

Davis and Moore

Kingsley Davis and Wilbert E. Moore (1945) gave an argument for social stratification based on the idea of "functional necessity" (also known as the Davis-Moore hypothesis).

They argue that the most difficult jobs in any society have the highest

incomes in order to motivate individuals to fill the roles needed by

the division of labor. Thus inequality serves social stability.

This argument has been criticized as fallacious from a number of different angles: the argument is both that the individuals who are the most deserving are the highest rewarded, and that a system of unequal rewards

is necessary, otherwise no individuals would perform as needed for the

society to function. The problem is that these rewards are supposed to

be based upon objective merit, rather than subjective "motivations." The

argument also does not clearly establish why some positions are worth

more than others, even when they benefit more people in society, e.g.,

teachers compared to athletes and movie stars. Critics have suggested

that structural inequality (inherited wealth, family power, etc.) is itself a cause of individual success or failure, not a consequence of it.

Robert Merton

Robert K. Merton made important refinements to functionalist thought.

He fundamentally agreed with Parsons' theory. However, he acknowledged

Parsons' theory problematic, believing that it was over generalized. Merton tended to emphasize middle range theory rather than a grand theory,

meaning that he was able to deal specifically with some of the

limitations in Parsons' theory. Merton believed that any social

structure probably has many functions, some more obvious than others. He identified 3 main limitations: functional unity, universal functionalism and indispensability. He also developed the concept of deviance and made the distinction between manifest and latent functions.

Manifest functions referred to the recognized and intended consequences

of any social pattern. Latent functions referred to unrecognized and unintended consequences of any social pattern.

Merton criticized functional unity, saying that not all parts of a

modern complex society work for the functional unity of society.

Consequently, there is a social dysfunction referred to as any social

pattern that may disrupt the operation of society.

Some institutions and structures may have other functions, and some may

even be generally dysfunctional, or be functional for some while being

dysfunctional for others.

This is because not all structures are functional for society as a

whole. Some practices are only functional for a dominant individual or a

group.

There are two types of functions that Merton discusses the "manifest

functions" in that a social pattern can trigger a recognized and

intended consequence. The manifest function of education includes

preparing for a career by getting good grades, graduation and finding

good job. The second type of function is "latent functions", where a

social pattern results in an unrecognized or unintended consequence. The

latent functions of education include meeting new people,

extra-curricular activities, school trips.

Another type of social function is "social dysfunction" which is any

undesirable consequences that disrupts the operation of society.

The social dysfunction of education includes not getting good grades, a

job. Merton states that by recognizing and examining the dysfunctional

aspects of society we can explain the development and persistence of

alternatives. Thus, as Holmwood states, "Merton explicitly made power

and conflict central issues for research within a functionalist

paradigm."

Merton also noted that there may be functional alternatives to

the institutions and structures currently fulfilling the functions of

society. This means that the institutions that currently exist are not

indispensable to society. Merton states "just as the same item may have

multiple functions, so may the same function be diversely fulfilled by

alternative items."

This notion of functional alternatives is important because it reduces

the tendency of functionalism to imply approval of the status quo.

Merton's theory of deviance is derived from Durkheim's idea of anomie.

It is central in explaining how internal changes can occur in a system.

For Merton, anomie means a discontinuity between cultural goals and the

accepted methods available for reaching them.

Merton believes that there are 5 situations facing an actor.

- Conformity occurs when an individual has the means and desire to achieve the cultural goals socialized into them.

- Innovation occurs when an individual strives to attain the accepted cultural goals but chooses to do so in novel or unaccepted method.

- Ritualism occurs when an individual continues to do things as prescribed by society but forfeits the achievement of the goals.

- Retreatism is the rejection of both the means and the goals of society.

- Rebellion is a combination of the rejection of societal goals and means and a substitution of other goals and means.

Thus it can be seen that change can occur internally in society

through either innovation or rebellion. It is true that society will

attempt to control these individuals and negate the changes, but as the

innovation or rebellion builds momentum, society will eventually adapt

or face dissolution.

Almond and Powell

In the 1970s, political scientists Gabriel Almond and Bingham Powell introduced a structural-functionalist approach to comparing political systems.

They argued that, in order to understand a political system, it is

necessary to understand not only its institutions (or structures) but

also their respective functions. They also insisted that these

institutions, to be properly understood, must be placed in a meaningful

and dynamic historical context.

This idea stood in marked contrast to prevalent approaches in the

field of comparative politics—the state-society theory and the dependency theory. These were the descendants of David Easton's system theory in international relations,

a mechanistic view that saw all political systems as essentially the

same, subject to the same laws of "stimulus and response"—or inputs and

outputs—while paying little attention to unique characteristics. The

structural-functional approach is based on the view that a political

system is made up of several key components, including interest groups, political parties and branches of government.

In addition to structures, Almond and Powell showed that a

political system consists of various functions, chief among them

political socialization, recruitment and communication: socialization refers to the way in which societies pass along their values and beliefs to succeeding generations,

and in political terms describe the process by which a society

inculcates civic virtues, or the habits of effective citizenship;

recruitment denotes the process by which a political system generates

interest, engagement and participation from citizens; and communication

refers to the way that a system promulgates its values and information.

Unilineal descent

In their attempt to explain the social stability of African "primitive" stateless societies where they undertook their fieldwork, Evans-Pritchard (1940) and Meyer Fortes (1945) argued that the Tallensi and the Nuer were primarily organized around unilineal descent

groups. Such groups are characterized by common purposes, such as

administering property or defending against attacks; they form a

permanent social structure that persists well beyond the lifespan of

their members. In the case of the Tallensi and the Nuer, these corporate

groups were based on kinship which in turn fitted into the larger

structures of unilineal descent; consequently Evans-Pritchard's and

Fortes' model is called "descent theory". Moreover, in this African

context territorial divisions were aligned with lineages; descent theory

therefore synthesized both blood and soil as the same. Affinal ties

with the parent through whom descent is not reckoned, however, are

considered to be merely complementary or secondary (Fortes created the

concept of "complementary filiation"), with the reckoning of kinship

through descent being considered the primary organizing force of social

systems. Because of its strong emphasis on unilineal descent, this new

kinship theory came to be called "descent theory".

With no delay, descent theory had found its critics. Many African

tribal societies seemed to fit this neat model rather well, although Africanists, such as Paul Richards,

also argued that Fortes and Evans-Pritchard had deliberately downplayed

internal contradictions and overemphasized the stability of the local

lineage systems and their significance for the organization of society. However, in many Asian settings the problems were even more obvious. In Papua New Guinea, the local patrilineal descent

groups were fragmented and contained large amounts of non-agnates.

Status distinctions did not depend on descent, and genealogies were too

short to account for social solidarity through identification with a

common ancestor. In particular, the phenomenon of cognatic

(or bilateral) kinship posed a serious problem to the proposition that

descent groups are the primary element behind the social structures of

"primitive" societies.

Leach's (1966) critique came in the form of the classical Malinowskian

argument, pointing out that "in Evans-Pritchard's studies of the Nuer

and also in Fortes's studies of the Tallensi unilineal descent turns out

to be largely an ideal concept to which the empirical facts are only

adapted by means of fictions."

People's self-interest, maneuvering, manipulation and competition had

been ignored. Moreover, descent theory neglected the significance of

marriage and affinal ties, which were emphasized by Levi-Strauss' structural anthropology,

at the expense of overemphasizing the role of descent. To quote Leach:

"The evident importance attached to matrilateral and affinal kinship

connections is not so much explained as explained away."

Decline of functionalism

Structural functionalism reached the peak of its influence in the 1940s and 1950s, and by the 1960s was in rapid decline. By the 1980s, its place was taken in Europe by more conflict-oriented approaches, and more recently by structuralism.

While some of the critical approaches also gained popularity in the

United States, the mainstream of the discipline has instead shifted to a

myriad of empirically-oriented middle-range theories with no overarching theoretical orientation. To most sociologists, functionalism is now "as dead as a dodo".

As the influence of functionalism in the 1960s began to wane, the linguistic and cultural turns

led to a myriad of new movements in the social sciences: "According to

Giddens, the orthodox consensus terminated in the late 1960s and 1970s

as the middle ground shared by otherwise competing perspectives gave way

and was replaced by a baffling variety of competing perspectives. This

third generation of social theory includes phenomenologically inspired approaches, critical theory, ethnomethodology, symbolic interactionism, structuralism, post-structuralism, and theories written in the tradition of hermeneutics and ordinary language philosophy."

While absent from empirical sociology, functionalist themes

remained detectable in sociological theory, most notably in the works of

Luhmann

and Giddens. There are, however, signs of an incipient revival, as

functionalist claims have recently been bolstered by developments in multilevel selection theory and in empirical research on how groups solve social dilemmas. Recent developments in evolutionary theory—especially by biologist David Sloan Wilson and anthropologists Robert Boyd and Peter Richerson—have

provided strong support for structural functionalism in the form of

multilevel selection theory. In this theory, culture and social

structure are seen as a Darwinian (biological or cultural) adaptation at the group level.

Criticisms

In the 1960s, functionalism was criticized for being unable to

account for social change, or for structural contradictions and conflict

(and thus was often called "consensus theory").

Also, it ignores inequalities including race, gender, class, which

cause tension and conflict. The refutation of the second criticism of

functionalism, that it is static and has no concept of change, has

already been articulated above, concluding that while Parsons' theory

allows for change, it is an orderly process of change [Parsons,

1961:38], a moving equilibrium. Therefore, referring to Parsons' theory

of society as static is inaccurate. It is true that it does place

emphasis on equilibrium and the maintenance or quick return to social

order, but this is a product of the time in which Parsons was writing

(post-World War II, and the start of the cold war). Society was in

upheaval and fear abounded. At the time social order was crucial, and

this is reflected in Parsons' tendency to promote equilibrium and social

order rather than social change.

Furthermore, Durkheim favored a radical form of guild socialism along with functionalist explanations. Also, Marxism,

while acknowledging social contradictions, still uses functionalist

explanations. Parsons' evolutionary theory describes the differentiation

and reintegration systems and subsystems and thus at least temporary

conflict before reintegration.

"The fact that functional analysis can be seen by some as inherently

conservative and by others as inherently radical suggests that it may be

inherently neither one nor the other."

Stronger criticisms include the epistemological argument that functionalism is tautologous,

that is it attempts to account for the development of social

institutions solely through recourse to the effects that are attributed

to them and thereby explains the two circularly. However, Parsons drew

directly on many of Durkheim's concepts in creating his theory.

Certainly Durkheim was one of the first theorists to explain a

phenomenon with reference to the function it served for society. He

said, "the determination of function is…necessary for the complete

explanation of the phenomena."

However Durkheim made a clear distinction between historical and

functional analysis, saying, "When ... the explanation of a social

phenomenon is undertaken, we must seek separately the efficient cause

which produces it and the function it fulfills."

If Durkheim made this distinction, then it is unlikely that Parsons did

not. However Merton does explicitly state that functional analysis does

not seek to explain why the action happened in the first instance, but

why it continues or is reproduced. By this particular logic, it can be

argued that functionalists do not necessarily explain the original cause

of a phenomenon with reference to its effect. Yet the logic stated in

reverse, that social phenomena are (re)produced because they serve ends,

is unoriginal to functionalist thought. Thus functionalism is either

undefinable or it can be defined by the teleological arguments which

functionalist theorists normatively produced before Merton.

Another criticism describes the ontological argument that society cannot have "needs" as a human being does, and even if society does have needs they need not be met. Anthony Giddens

argues that functionalist explanations may all be rewritten as

historical accounts of individual human actions and consequences.

A further criticism directed at functionalism is that it contains no sense of agency,

that individuals are seen as puppets, acting as their role requires.

Yet Holmwood states that the most sophisticated forms of functionalism

are based on "a highly developed concept of action,"

and as was explained above, Parsons took as his starting point the

individual and their actions. His theory did not however articulate how

these actors exercise their agency in opposition to the socialization

and inculcation of accepted norms. As has been shown above, Merton

addressed this limitation through his concept of deviance, and so it can

be seen that functionalism allows for agency. It cannot, however,

explain why individuals choose to accept or reject the accepted norms,

why and in what circumstances they choose to exercise their agency, and

this does remain a considerable limitation of the theory.

Further criticisms have been levelled at functionalism by proponents of other social theories, particularly conflict theorists, Marxists, feminists and postmodernists.

Conflict theorists criticized functionalism's concept of systems as

giving far too much weight to integration and consensus, and neglecting

independence and conflict.

Lockwood, in line with conflict theory, suggested that Parsons' theory

missed the concept of system contradiction. He did not account for those

parts of the system that might have tendencies to mal-integration.

According to Lockwood, it was these tendencies that come to the surface

as opposition and conflict among actors. However Parsons thought that

the issues of conflict and cooperation were very much intertwined and

sought to account for both in his model.

In this however he was limited by his analysis of an ‘ideal type' of

society which was characterized by consensus. Merton, through his

critique of functional unity, introduced into functionalism an explicit

analysis of tension and conflict. Yet Merton's functionalist

explanations of social phenomena continued to rest on the idea that

society is primarily co-operative rather than conflicted, which

differentiates Merton from conflict theorists.

Marxism, which was revived soon after the emergence of conflict

theory, criticized professional sociology (functionalism and conflict

theory alike) for being partisan to advanced welfare capitalism.

Gouldner thought that Parsons' theory specifically was an expression of

the dominant interests of welfare capitalism, that it justified

institutions with reference to the function they fulfill for society.

It may be that Parsons' work implied or articulated that certain

institutions were necessary to fulfill the functional prerequisites of

society, but whether or not this is the case, Merton explicitly states

that institutions are not indispensable and that there are functional

alternatives. That he does not identify any alternatives to the current

institutions does reflect a conservative bias, which as has been stated

before is a product of the specific time that he was writing in.

As functionalism's prominence was ending, feminism was on the

rise, and it attempted a radical criticism of functionalism. It believed

that functionalism neglected the suppression of women within the family

structure. Holmwood

shows, however, that Parsons did in fact describe the situations where

tensions and conflict existed or were about to take place, even if he

did not articulate those conflicts. Some feminists agree, suggesting

that Parsons' provided accurate descriptions of these situations.

On the other hand, Parsons recognized that he had oversimplified his

functional analysis of women in relation to work and the family, and

focused on the positive functions of the family for society and not on

its dysfunctions for women. Merton, too, although addressing situations

where function and dysfunction occurred simultaneously, lacked a

"feminist sensibility."

Postmodernism, as a theory, is critical of claims of objectivity. Therefore, the idea of grand theory and grand narrative

that can explain society in all its forms is treated with skepticism.

This critique focuses on exposing the danger that grand theory can pose

when not seen as a limited perspective, as one way of understanding

society.

Jeffrey Alexander

(1985) sees functionalism as a broad school rather than a specific

method or system, such as Parsons, who is capable of taking equilibrium

(stability) as a reference-point rather than assumption and treats

structural differentiation as a major form of social change. The name

'functionalism' implies a difference of method or interpretation that

does not exist.

This removes the determinism criticized above. Cohen argues that rather

than needs a society has dispositional facts: features of the social

environment that support the existence of particular social institutions

but do not cause them.