| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cobalt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | hard lustrous bluish gray metal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar, std(Co) | 58.933194(3) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cobalt in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 27 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | transition metal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d7 4s2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Electrons per shell

| 2, 8, 15, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1768 K (1495 °C, 2723 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 3200 K (2927 °C, 5301 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 8.90 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 8.86 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 16.06 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 377 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.81 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −3, −1, +1, +2, +3, +4, +5 (an amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.88 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 125 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | Low spin: 126±3 pm High spin: 150±7 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spectral lines of cobalt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | hexagonal close-packed (hcp) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 4720 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 13.0 µm/(m·K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 100 W/(m·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 62.4 nΩ·m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | ferromagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 209 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 75 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 180 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 5.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 1043 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 470–3000 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-48-4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Georg Brandt (1735) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main isotopes of cobalt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cobalt is a chemical element with symbol Co and atomic number 27. Like nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, produced by reductive smelting, is a hard, lustrous, silver-gray metal.

Cobalt-based blue pigments (cobalt blue) have been used since ancient times for jewelry and paints, and to impart a distinctive blue tint to glass, but the color was later thought by alchemists to be due to the known metal bismuth. Miners had long used the name kobold ore (German for goblin ore) for some of the blue-pigment producing minerals; they were so named because they were poor in known metals, and gave poisonous arsenic-containing fumes when smelted. In 1735, such ores were found to be reducible to a new metal (the first discovered since ancient times), and this was ultimately named for the kobold.

Today, some cobalt is produced specifically from one of a number of metallic-lustered ores, such as for example cobaltite (CoAsS). The element is however more usually produced as a by-product of copper and nickel mining. The copper belt in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Zambia yields most of the global cobalt production. The DRC alone accounted for more than 50% of world production in 2016 (123,000 tonnes), according to Natural Resources Canada.

Cobalt is primarily used in the manufacture of magnetic, wear-resistant and high-strength alloys. The compounds cobalt silicate and cobalt(II) aluminate (CoAl2O4, cobalt blue) give a distinctive deep blue color to glass, ceramics, inks, paints and varnishes. Cobalt occurs naturally as only one stable isotope, cobalt-59. Cobalt-60 is a commercially important radioisotope, used as a radioactive tracer and for the production of high energy gamma rays.

Cobalt is the active center of a group of coenzymes called cobalamins. vitamin B12, the best-known example of the type, is an essential vitamin for all animals. Cobalt in inorganic form is also a micronutrient for bacteria, algae, and fungi.

Characteristics

A block of electrolytically refined cobalt (99.9% purity) cut from a large plate

Cobalt is a ferromagnetic metal with a specific gravity of 8.9. The Curie temperature is 1,115 °C (2,039 °F) and the magnetic moment is 1.6–1.7 Bohr magnetons per atom. Cobalt has a relative permeability two-thirds that of iron. Metallic cobalt occurs as two crystallographic structures: hcp and fcc.

The ideal transition temperature between the hcp and fcc structures is

450 °C (842 °F), but in practice the energy difference between them is

so small that random intergrowth of the two is common.

Cobalt is a weakly reducing metal that is protected from oxidation by a passivating oxide film. It is attacked by halogens and sulfur. Heating in oxygen produces Co3O4 which loses oxygen at 900 °C (1,650 °F) to give the monoxide CoO. The metal reacts with fluorine (F2) at 520 K to give CoF3; with chlorine (Cl2), bromine (Br2) and iodine (I2), producing equivalent binary halides. It does not react with hydrogen gas (H2) or nitrogen gas (N2) even when heated, but it does react with boron, carbon, phosphorus, arsenic and sulfur.[12] At ordinary temperatures, it reacts slowly with mineral acids, and very slowly with moist, but not with dry, air.

Compounds

Common oxidation states of cobalt include +2 and +3, although compounds with oxidation states ranging from −3 to +5 are also known. A common oxidation state for simple compounds is +2 (cobalt(II)). These salts form the pink-colored metal aquo complex [Co(H2O)6]2+ in water. Addition of chloride gives the intensely blue [CoCl

4]2−. In a borax bead flame test, cobalt shows deep blue in both oxidizing and reducing flames.

4]2−. In a borax bead flame test, cobalt shows deep blue in both oxidizing and reducing flames.

Oxygen and chalcogen compounds

Several oxides of cobalt are known. Green cobalt(II) oxide (CoO) has rocksalt structure. It is readily oxidized with water and oxygen to brown cobalt(III) hydroxide (Co(OH)3). At temperatures of 600–700 °C, CoO oxidizes to the blue cobalt(II,III) oxide (Co3O4), which has a spinel structure. Black cobalt(III) oxide (Co2O3) is also known.[14] Cobalt oxides are antiferromagnetic at low temperature: CoO (Néel temperature 291 K) and Co3O4 (Néel temperature: 40 K), which is analogous to magnetite (Fe3O4), with a mixture of +2 and +3 oxidation states.

The principal chalcogenides of cobalt include the black cobalt(II) sulfides, CoS2, which adopts a pyrite-like structure, and cobalt(III) sulfide (Co2S3).

Halides

Cobalt(II) chloride hexahydrate

Four dihalides of cobalt(II) are known: cobalt(II) fluoride (CoF2, pink), cobalt(II) chloride (CoCl2, blue), cobalt(II) bromide (CoBr2, green), cobalt(II) iodide (CoI2,

blue-black). These halides exist in anhydrous and hydrated forms.

Whereas the anhydrous dichloride is blue, the hydrate is red.

The reduction potential for the reaction Co3+ + e− → Co2+ is +1.92 V, beyond that for chlorine

to chloride, +1.36 V. Consequently, cobalt(III) and chloride would

result in the cobalt(III) being reduced to cobalt(II). Because the

reduction potential for fluorine to fluoride is so high, +2.87 V, cobalt(III) fluoride

is one of the few simple stable cobalt(III) compounds. Cobalt(III)

fluoride, which is used in some fluorination reactions, reacts

vigorously with water.

Coordination compounds

As for all metals, molecular compounds and polyatomic ions of cobalt are classified as coordination complexes, that is, molecules or ions that contain cobalt linked to several ligands. The principles of electronegativity and hardness–softness of a series of ligands can be used to explain the usual oxidation state of cobalt. For example, Co+3 complexes tend to have ammine ligands. Because phosphorus is softer than nitrogen, phosphine ligands tend to feature the softer Co2+ and Co+, an example being tris(triphenylphosphine)cobalt(I) chloride ((P(C6H5)3)3CoCl). The more electronegative (and harder) oxide and fluoride can stabilize Co4+ and Co5+ derivatives, e.g. caesium hexafluorocobaltate (Cs2CoF6) and potassium percobaltate (K3CoO4).

Alfred Werner, a Nobel-prize winning pioneer in coordination chemistry, worked with compounds of empirical formula [Co(NH3)6]3+. One of the isomers determined was cobalt(III) hexammine chloride. This coordination complex, a typical Werner-type complex, consists of a central cobalt atom coordinated by six ammine orthogonal ligands and three chloride counteranions. Using chelating ethylenediamine ligands in place of ammonia gives tris(ethylenediamine)cobalt(III) ([Co(en)3]3+), which was one of the first coordination complexes to be resolved into optical isomers.

The complex exists in the right- and left-handed forms of a

"three-bladed propeller". This complex was first isolated by Werner as

yellow-gold needle-like crystals.

Organometallic compounds

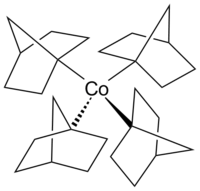

Structure of tetrakis(1-norbornyl)cobalt(IV)

Cobaltocene is a structural analog to ferrocene, with cobalt in place of iron. Cobaltocene is much more sensitive to oxidation than ferrocene. Cobalt carbonyl (Co2(CO)8) is a catalyst in carbonylation and hydrosilylation reactions. Vitamin B12 (see below) is an organometallic compound found in nature and is the only vitamin that contains a metal atom. An example of an alkylcobalt complex in the otherwise uncommon +4 oxidation state of cobalt is the homoleptic complex tetrakis(1-norbornyl)cobalt(IV) (Co(1-norb)4), a transition metal-alkyl complex that is notable for its stability to β-hydrogen elimination. The cobalt(III) and cobalt(V) complexes [Li(THF)4]+[Co(1-norb)4]− and [Co(1-norb)4]+[BF4]− are also known.

Isotopes

59Co is the only stable cobalt isotope and the only isotope that exists naturally on Earth. Twenty-two radioisotopes have been characterized; the most stable, 60Co has a half-life of 5.2714 years, and 57Co has a half-life of 271.8 days, 56Co a half-life of 77.27 days, and 58Co a half-life of 70.86 days. All the other radioactive isotopes of cobalt have half-lives shorter than 18 hours, and in most cases shorter than 1 second. This element also has 4 meta states, all of which have half-lives shorter than 15 minutes.

The isotopes of cobalt range in atomic weight from 50 u (50Co) to 73 u (73Co). The primary decay mode for isotopes with atomic mass unit values less than that of the most abundant stable isotope, 59Co, is electron capture and the primary mode of decay in isotopes with atomic mass greater than 59 atomic mass units is beta decay. The primary decay products below 59Co are element 26 (iron) isotopes; above that the decay products are element 28 (nickel) isotopes.

History

Early Chinese blue and white porcelain, manufactured c. 1335

Cobalt compounds have been used for centuries to impart a rich blue color to glass, glazes, and ceramics. Cobalt has been detected in Egyptian sculpture, Persian jewelry from the third millennium BC, in the ruins of Pompeii, destroyed in 79 AD, and in China, dating from the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD) and the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 AD).

Cobalt has been used to color glass since the Bronze Age. The excavation of the Uluburun shipwreck yielded an ingot of blue glass, cast during the 14th century BC. Blue glass from Egypt was either colored with copper, iron, or cobalt. The oldest cobalt-colored glass is from the eighteenth dynasty of Egypt (1550–1292 BC). The source for the cobalt the Egyptians used is not known.

The word cobalt is derived from the German kobalt, from kobold meaning "goblin", a superstitious term used for the ore

of cobalt by miners. The first attempts to smelt those ores for copper

or nickel failed, yielding simply powder (cobalt(II) oxide) instead.

Because the primary ores of cobalt always contain arsenic, smelting the

ore oxidized the arsenic into the highly toxic and volatile arsenic oxide, adding to the notoriety of the ore.

Swedish chemist Georg Brandt

(1694–1768) is credited with discovering cobalt circa 1735, showing it

to be a previously unknown element, different from bismuth and other

traditional metals. Brandt called it a new "semi-metal".

He showed that compounds of cobalt metal were the source of the blue

color in glass, which previously had been attributed to the bismuth

found with cobalt. Cobalt became the first metal to be discovered since

the pre-historical period. All other known metals (iron, copper,

silver, gold, zinc, mercury, tin, lead and bismuth) had no recorded

discoverers.

During the 19th century, a significant part of the world's production of cobalt blue (a dye made with cobalt compounds and alumina) and smalt (cobalt glass powdered for use for pigment purposes in ceramics and painting) was carried out at the Norwegian Blaafarveværket. The first mines for the production of smalt in the 16th century were located in Norway, Sweden, Saxony and Hungary. With the discovery of cobalt ore in New Caledonia in 1864, the mining of cobalt in Europe declined. With the discovery of ore deposits in Ontario, Canada in 1904 and the discovery of even larger deposits in the Katanga Province in the Congo in 1914, the mining operations shifted again. When the Shaba conflict started in 1978, the copper mines of Katanga Province nearly stopped production.

The impact on the world cobalt economy from this conflict was smaller

than expected: cobalt is a rare metal, the pigment is highly toxic, and

the industry had already established effective ways for recycling cobalt

materials. In some cases, industry was able to change to cobalt-free

alternatives.

In 1938, John Livingood and Glenn T. Seaborg discovered the radioisotope cobalt-60. This isotope was famously used at Columbia University in the 1950s to establish parity violation in radioactive beta decay.

After World War II, the US wanted to guarantee the supply of

cobalt ore for military uses (as the Germans had been doing) and

prospected for cobalt within the U.S. border. An adequate supply of the

ore was found in Idaho near Blackbird canyon in the side of a mountain. The firm Calera Mining Company started production at the site.

Occurrence

The stable form of cobalt is produced in supernovas through the r-process. It comprises 0.0029% of the Earth's crust. Free cobalt (the native metal)

is not found on Earth because of the oxygen in the atmosphere and the

chlorine in the ocean. Both are abundant enough in the upper layers of

the Earth's crust to prevent native metal cobalt from forming. Except as

recently delivered in meteoric iron, pure cobalt in native metal form

is unknown on Earth. The element has a medium abundance but natural

compounds of cobalt are numerous and small amounts of cobalt compounds

are found in most rocks, soils, plants, and animals.

In nature, cobalt is frequently associated with nickel. Both are characteristic components of meteoric iron, though cobalt is much less abundant in iron meteorites than nickel. As with nickel, cobalt in meteoric iron alloys may have been well enough protected from oxygen and moisture to remain as the free (but alloyed) metal, though neither element is seen in that form in the ancient terrestrial crust.

Cobalt in compound form occurs in copper and nickel minerals. It is the major metallic component that combines with sulfur and arsenic in the sulfidic cobaltite (CoAsS), safflorite (CoAs2), glaucodot ((Co,Fe)AsS), and skutterudite (CoAs3) minerals. The mineral cattierite is similar to pyrite and occurs together with vaesite in the copper deposits of Katanga Province. When it reaches the atmosphere, weathering occurs; the sulfide minerals oxidize and form pink erythrite ("cobalt glance": Co3(AsO4)2·8H2O) and spherocobaltite (CoCO3).

Cobalt is also a constituent of tobacco smoke. The tobacco plant readily absorbs and accumulates heavy metals like cobalt from the surrounding soil in its leaves. These are subsequently inhaled during tobacco smoking.

Production

Cobalt ore

World production trend

The main ores of cobalt are cobaltite, erythrite, glaucodot and skutterudite (see above), but most cobalt is obtained by reducing the cobalt by-products of nickel and copper mining and smelting.

Since cobalt is generally produced as a by-product, the supply of

cobalt depends to a great extent on the economic feasibility of copper

and nickel mining in a given market. Demand for cobalt was projected to

grow 6% in 2017.

Several methods exist to separate cobalt from copper and nickel,

depending on the concentration of cobalt and the exact composition of

the used ore. One method is froth flotation, in which surfactants bind to different ore components, leading to an enrichment of cobalt ores. Subsequent roasting converts the ores to cobalt sulfate, and the copper and the iron are oxidized to the oxide. Leaching with water extracts the sulfate together with the arsenates. The residues are further leached with sulfuric acid, yielding a solution of copper sulfate. Cobalt can also be leached from the slag of copper smelting.

The products of the above-mentioned processes are transformed into the cobalt oxide (Co3O4). This oxide is reduced to metal by the aluminothermic reaction or reduction with carbon in a blast furnace.

Cobalt extraction

The United States Geological Survey estimates world reserves of cobalt at 7,100,000 metric tons. The Democratic Republic of the Congo

(DRC) currently produces 63% of the world’s cobalt. This market share

may reach 73% by 2025 if planned expansions by mining producers like Glencore

Plc take place as expected. But by 2030, global demand could be 47

times more than it was in 2017, Bloomberg New Energy Finance has

estimated.

Changes that Congo made to mining laws in 2002 attracted new

investments in Congolese copper and cobalt projects. Glencore's Mutanda

mine shipped 24,500 tons of cobalt last year, 40% of Congo DRC’s output

and nearly a quarter of global production. Glencore’s Katanga Mining

project is resuming as well and should produce 300,000 tons of copper

and 20,000 tons of cobalt by 2019, according to Glencore.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

In 2005, the top producer of cobalt was the copper deposits in the Democratic Republic of the Congo's Katanga Province. Formerly Shaba province, the area had almost 40% of global reserves, reported the British Geological Survey in 2009.

By 2015, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) supplied 60% of world

cobalt production, 32,000 tons at $20,000 to $26,000 per ton. Recent

growth in production could at least partly be due to how low mining

production fell during DRC Congo's very violent civil wars in the early

2000s, or to the changes the country made to its Mining Code in 2002 to

encourage foreign and multinational investment and which did bring in a

number of investors, including Glencore.

Artisanal mining supplied 10% to 25% of the DRC production.

Some 100,000 cobalt miners in Congo DRC use hand tools to dig hundreds

of feet, with little planning and fewer safety measures, say workers and

government and NGO officials, as well as Washington Post reporters' observations on visits to isolated mines. The lack of safety precautions frequently causes injuries or death.

Mining pollutes the vicinity and exposes local wildlife and indigenous

communities to toxic metals thought to cause birth defects and breathing

difficulties, according to health officials.

Human rights activists have alleged, and investigative journalism reported confirmation, that child labor is used in mining cobalt from African artisanal mines. This revelation prompted cell phone maker Apple Inc., on March 3, 2017, to stop buying ore from suppliers such as Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt who source from artisanal mines in the DRC, and begin using only suppliers that are verified to meet its workplace standards.

The political and ethnic dynamics of the region have in the past

caused horrific outbreaks of violence and years of armed conflict and

displaced populations. This instability affected the price of cobalt and

also created perverse incentives for the combatants in the First and

Second Congo Wars to prolong the fighting, since access to diamond mines

and other valuable resources helped to finance their military

goals—which frequently amounted to genocide—and also enriched the

fighters themselves. While DR Congo has in the 2010s not recently been

invaded by neighboring military forces, some of the richest mineral

deposits adjoin areas where Tutsis and Hutus still frequently clash,

unrest continues although on a smaller scale and refugees still flee

outbreaks of violence.

Cobalt extracted from small Congolese artisanal mining endeavors in 2007 supplied a single Chinese company, Congo DongFang International Mining. A subsidiary of Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt,

one of the world’s largest cobalt producers, Congo DongFang supplied

cobalt to some of the world’s largest battery manufacturers, who

produced batteries for ubiquitous products like the Apple iPhones. Corporate pieties about an ethical supply chain

were thus met with some incredulity. A number of observers have called

for tech corporations and other manufacturers to avoid sourcing conflict

metals in Central Africa at all rather than risk enabling the financial

exploitation, human rights abuses like kidnappings for unfree labor, environmental devastation and the human toll of violence, poverty and toxic conditions.

The Mukondo Mountain project, operated by the Central African Mining and Exploration Company (CAMEC) in Katanga Province,

may be the richest cobalt reserve in the world. It produced an

estimated one third of the total global coval production in 2008. In July 2009, CAMEC announced a long-term agreement to deliver its entire annual production of cobalt concentrate from Mukondo Mountain to Zhejiang Galico Cobalt & Nickel Materials of China.

In February 2018, global asset management firm AllianceBernstein defined the DRC as economically "the Saudi Arabia of the electric vehicle age," due to its cobalt resources, as essential to the lithium-ion batteries that drive electric vehicles.

On March 9, 2018, President Joseph Kabila updated the 2002 mining code, increasing royalty charges and declaring cobalt and coltan "strategic metals".

Canada

In 2017, some exploration companies were planning to survey old silver and cobalt mines in the area of Cobalt, Ontario where significant deposits are believed to lie.

The mayor of Cobalt stated that the people of Cobalt welcomed new

mining endeavours and pointed out that the local work force is peaceful

and English-speaking, and good infrastructure would allow much easier

sourcing of spare parts for the equipment or other supplies than were to

be found in conflict-zones.

Applications

Cobalt has been used in production of high-performance alloys.

It can also be used to make rechargeable batteries, and the advent of

electric vehicles and their success with consumers probably has a great

deal to do with the DRC's soaring production. Other important factors

were the 2002 Mining Code, which encouraged investment by foreign and

transnational corporations such as Glencore, and the end of the First

and Second Congo Wars.

Alloys

Cobalt-based superalloys have historically consumed most of the cobalt produced. The temperature stability of these alloys makes them suitable for turbine blades for gas turbines and aircraft jet engines, although nickel-based single-crystal alloys surpass them in performance. Cobalt-based alloys are also corrosion- and wear-resistant, making them, like titanium, useful for making orthopedic implants

that don't wear down over time. The development of wear-resistant

cobalt alloys started in the first decade of the 20th century with the stellite alloys, containing chromium with varying quantities of tungsten and carbon. Alloys with chromium and tungsten carbides are very hard and wear-resistant. Special cobalt-chromium-molybdenum alloys like Vitallium are used for prosthetic parts (hip and knee replacements). Cobalt alloys are also used for dental prosthetics as a useful substitute for nickel, which may be allergenic. Some high-speed steels also contain cobalt for increased heat and wear resistance. The special alloys of aluminium, nickel, cobalt and iron, known as Alnico, and of samarium and cobalt (samarium-cobalt magnet) are used in permanent magnets. It is also alloyed with 95% platinum for jewelry, yielding an alloy suitable for fine casting, which is also slightly magnetic.

Batteries

Lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO2) is widely used in lithium-ion battery cathodes. The material is composed of cobalt oxide layers with the lithium intercalated. During discharge, the lithium is released as lithium ions. Nickel-cadmium (NiCd) and nickel metal hydride (NiMH) batteries also include cobalt to improve the oxidation of nickel in the battery.

Transparency Market Research estimated the global lithium-ion battery

market at $30 billion in 2015 and predicted an increase to over US$75

billion by 2024.

Although in 2018 most cobalt in batteries was used in a mobile device,

a more recent application for cobalt is rechargeable batteries for

electric cars. This industry has increased five-fold in its demand for

cobalt, which makes it urgent to find new raw materials in more stable

areas of the world. Demand is expected to continue or increase as the prevalence of electric vehicles increases. Exploration in 2016–2017 included the area around Cobalt, Ontario, an area where many silver mines ceased operation decades ago.

Since child and slave labor have been repeatedly reported in

cobalt mining, primarily in the artisanal mines of DR Congo, tech

companies seeking an ethical supply chain have faced shortages of this

raw material and the price of cobalt metal reached a nine-year high in October 2017, more than US$30 a pound, versus US$10 in late 2015.

Catalysts

Several cobalt compounds are oxidation catalysts. Cobalt acetate is used to convert xylene to terephthalic acid, the precursor of the bulk polymer polyethylene terephthalate. Typical catalysts are the cobalt carboxylates (known as cobalt soaps). They are also used in paints, varnishes, and inks as "drying agents" through the oxidation of drying oils.

The same carboxylates are used to improve the adhesion between steel

and rubber in steel-belted radial tires. In addition they are used as

accelerators in polyester resin systems.

Cobalt-based catalysts are used in reactions involving carbon monoxide. Cobalt is also a catalyst in the Fischer–Tropsch process for the hydrogenation of carbon monoxide into liquid fuels. Hydroformylation of alkenes often uses cobalt octacarbonyl as a catalyst, although it is often replaced by more efficient iridium- and rhodium-based catalysts, e.g. the Cativa process.

The hydrodesulfurization of petroleum

uses a catalyst derived from cobalt and molybdenum. This process helps

to clean petroleum of sulfur impurities that interfere with the refining

of liquid fuels.

Pigments and coloring

Cobalt blue glass

Cobalt-colored glass

Before the 19th century, cobalt was predominantly used as a pigment. It has been used since the Middle Ages to make smalt, a blue-colored glass. Smalt is produced by melting a mixture of roasted mineral smaltite, quartz and potassium carbonate, which yields a dark blue silicate glass, which is finely ground after the production. Smalt was widely used to color glass and as pigment for paintings. In 1780, Sven Rinman discovered cobalt green, and in 1802 Louis Jacques Thénard discovered cobalt blue. Cobalt pigments such as cobalt blue (cobalt aluminate), cerulean blue (cobalt(II) stannate), various hues of cobalt green (a mixture of cobalt(II) oxide and zinc oxide), and cobalt violet (cobalt phosphate) are used as artist's pigments because of their superior chromatic stability. Aureolin (cobalt yellow) is now largely replaced by more lightfast yellow pigments.

Radioisotopes

Cobalt-60 (Co-60 or 60Co) is useful as a gamma-ray source because they can be produced in predictable quantity and high activity by bombarding cobalt with neutrons. It produces gamma rays with energies of 1.17 and 1.33 MeV.

Cobalt is used in external beam radiotherapy, sterilization of medical supplies and medical waste, radiation treatment of foods for sterilization (cold pasteurization), industrial radiography

(e.g. weld integrity radiographs), density measurements (e.g. concrete

density measurements), and tank fill height switches. The metal has the

unfortunate property of producing a fine dust, causing problems with radiation protection.

Cobalt from radiotherapy machines has been a serious hazard when not

discarded properly, and one of the worst radiation contamination

accidents in North America occurred in 1984, when a discarded

radiotherapy unit containing cobalt-60 was mistakenly disassembled in a

junkyard in Juarez, Mexico.

Cobalt-60 has a radioactive half-life of 5.27 years. Loss of

potency requires periodic replacement of the source in radiotherapy and

is one reason why cobalt machines have been largely replaced by linear accelerators in modern radiation therapy. Cobalt-57 (Co-57 or 57Co) is a cobalt radioisotope most often used in medical tests, as a radiolabel for vitamin B12 uptake, and for the Schilling test. Cobalt-57 is used as a source in Mössbauer spectroscopy and is one of several possible sources in X-ray fluorescence devices.

Nuclear weapon designs could intentionally incorporate 59Co, some of which would be activated in a nuclear explosion to produce 60Co. The 60Co, dispersed as nuclear fallout, is sometimes called a cobalt bomb.

Other uses

- Cobalt is used in electroplating for its attractive appearance, hardness, and resistance to oxidation;

- It is also used as a base primer coat for porcelain enamels.

Biological role

Cobalt-deficient sheep

Cobalt is essential to the metabolism of all animals. It is a key constituent of cobalamin, also known as vitamin B12, the primary biological reservoir of cobalt as an ultratrace element. Bacteria in the stomachs of ruminant animals convert cobalt salts into vitamin B12, a compound which can only be produced by bacteria or archaea. A minimal presence of cobalt in soils therefore markedly improves the health of grazing animals, and an uptake of 0.20 mg/kg a day is recommended because they have no other source of vitamin B12.

In the early 20th century, during the development of farming on the North Island Volcanic Plateau

of New Zealand, cattle suffered from what was termed "bush sickness".

It was discovered that the volcanic soils lacked the cobalt salts

essential for the cattle food chain.

The "coast disease" of sheep in the Ninety Mile Desert of the Southeast of South Australia

in the 1930s was found to originate in nutritional deficiencies of

trace elements cobalt and copper. The cobalt deficiency was overcome by

the development of "cobalt bullets", dense pellets of cobalt oxide mixed

with clay given orally for lodging in the animal's rumen.

Proteins based on cobalamin use corrin to hold the cobalt. Coenzyme B12 features a reactive C-Co bond that participates in the reactions. In humans, B12 has two types of alkyl ligand: methyl and adenosyl. MeB12 promotes methyl (−CH3) group transfers. The adenosyl version of B12

catalyzes rearrangements in which a hydrogen atom is directly

transferred between two adjacent atoms with concomitant exchange of the

second substituent, X, which may be a carbon atom with substituents, an

oxygen atom of an alcohol, or an amine. Methylmalonyl coenzyme A mutase (MUT) converts MMl-CoA to Su-CoA, an important step in the extraction of energy from proteins and fats.

Although far less common than other metalloproteins (e.g. those of zinc and iron), other cobaltoproteins are known besides B12. These proteins include methionine aminopeptidase 2, an enzyme that occurs in humans and other mammals that does not use the corrin ring of B12, but binds cobalt directly. Another non-corrin cobalt enzyme is nitrile hydratase, an enzyme in bacteria that metabolizes nitriles.

Precautions

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS signal word | Danger |

| H317, H334, H413 | |

| P261, P280, P342+311 | |

| NFPA 704 | |

Cobalt is an essential element for life in minute amounts. The LD50 value for soluble cobalt salts has been estimated to be between 150 and 500 mg/kg.[114] In the US, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has designated a permissible exposure limit (PEL) in the workplace as a time-weighted average (TWA) of 0.1 mg/m3. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a recommended exposure limit (REL) of 0.05 mg/m3, time-weighted average. The IDLH (immediately dangerous to life and health) value is 20 mg/m3.

However, chronic cobalt ingestion has caused serious health

problems at doses far less than the lethal dose. In 1966, the addition

of cobalt compounds to stabilize beer foam in Canada led to a peculiar form of toxin-induced cardiomyopathy, which came to be known as beer drinker's cardiomyopathy.

It causes respiratory problems when inhaled. It also causes skin problems when touched; after nickel and chromium, cobalt is a major cause of contact dermatitis. These risks are faced by cobalt miners.

Cobalt can be effectively absorbed by charred pigs' bones;

however, this process is inhibited by copper and zinc, which have

greater affinities to bone char.