| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | vitamin B12, vitamin B-12 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Routes of administration | by mouth, sublingual, IV, IM, intranasal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Readily absorbed in distal half of the ileum |

| Protein binding | Very high to specific transcobalamins plasma proteins Binding of hydroxocobalamin is slightly higher than cyanocobalamin. |

| Metabolism | liver |

| Elimination half-life | Approximately 6 days (400 days in the liver) |

| Excretion | kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C63H88CoN14O14P |

| Molar mass | 1355.388 g·mol−1 |

Vitamin B12, also called cobalamin, is a water-soluble vitamin that is involved in the metabolism of every cell of the human body: it is a cofactor in DNA synthesis, and in both fatty acid and amino acid metabolism. It is particularly important in the normal functioning of the nervous system via its role in the synthesis of myelin, and in the maturation of developing red blood cells in the bone marrow.

Vitamin B12 is one of eight B vitamins; it is the largest and most structurally complex vitamin. It consists of a class of chemically related compounds (vitamers), all of which show physiological activity. It contains the biochemically rare element cobalt (chemical symbol Co) positioned in the center of a corrin ring. The only organisms to produce vitamin B12 are certain bacteria, and archaea. Some of these bacteria are found in the soil around the grasses that ruminants eat; they are taken into the animal, proliferate, form part of their gut flora, and continue to produce vitamin B12.

Because there are no reliable vegetable sources of the vitamin, vegans must use a supplement or fortified foods for B12 intake or risk serious health consequences. Otherwise, most omnivorous people in developed countries obtain enough vitamin B12 from consuming animal products including meat, milk, eggs, and fish. Staple foods, especially those that form part of a vegan diet, are often fortified by having the vitamin added to them. Vitamin B12 supplements are available in single agent or multivitamin tablets; and pharmaceutical preparations may be given by intramuscular injection.

The most common cause of vitamin B12 deficiency in developed countries is impaired absorption due to a loss of gastric intrinsic factor, which must be bound to food-source B12 in order for absorption to occur. Another group affected are those on long term antacid therapy, using proton pump inhibitors, H2 blockers or other antacids. This condition may be characterised by limb neuropathy or a blood disorder called pernicious anemia, a type of megaloblastic anemia. Folate levels in the individual may affect the course of pathological changes and symptomatology. Deficiency is more likely after age 60, and increases in incidence with advancing age. Dietary deficiency is very rare in developed countries due to access to dietary meat and fortified foods, but children in some regions of developing countries are at particular risk due to increased requirements during growth coupled with lack of access to dietary B12; adults in these regions are also at risk. Other causes of vitamin B12 deficiency are much less frequent.

Chemistry

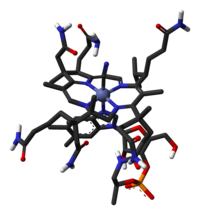

Methylcobalamin (shown) is a form of vitamin B12. Physically it resembles the other forms of vitamin B12, occurring as dark red crystals that freely form cherry-colored transparent solutions in water.

B12 is the most chemically complex of all the vitamins. The structure of B12 is based on a corrin ring, which is similar to the porphyrin ring found in heme. The central metal ion is cobalt. Four of the six coordination sites are provided by the corrin ring, and a fifth by a dimethylbenzimidazole group. The sixth coordination site, the reactive center, is variable, being a cyano group (–CN), a hydroxyl group (–OH), a methyl group (–CH3) or a 5′-deoxyadenosyl group (here the C5′ atom of the deoxyribose forms the covalent bond with cobalt respectively, to yield the four vitamers (forms) of B12. Historically, the covalent C-Co bond is one of the first examples of carbon-metal bonds to be discovered in biology. The hydrogenases and, by necessity, enzymes associated with cobalt utilization, involve metal-carbon bonds.

Vitamin B12 is a generic descriptor name referring to a collection of cobalt and corrin ring

molecules which are defined by their particular vitamin function in the

body. All of the substrate cobalt-corrin molecules from which B12

is made must be synthesized by bacteria. After this synthesis is

complete, the human body has the ability (except in rare cases) to

convert any form of B12 to an active form, by means of

enzymatically removing certain prosthetic chemical groups from the

cobalt atom and replacing them with others.

Vitamers

The four vitamers of B12 are all deeply red-colored crystals and water solutions, due to the color of the cobalt-corrin complex.

- Cyanocobalamin is one form of B12 because it can be metabolized in the body to an active coenzyme form. The cyanocobalamin form of B12 does not occur in nature normally, but is a byproduct of the fact that other forms of B12 are avid binders of cyanide (–CN) which they pick up in the process of activated charcoal purification of the vitamin after it is made by bacteria in the commercial process. Since the cyanocobalamin form of B12 is easy to crystallize and is not sensitive to air-oxidation, it is typically used as a form of B12 for food additives and in many common multivitamins. Pure cyanocobalamin possesses the deep pink color associated with most octahedral cobalt(II) complexes and the crystals are well formed and easily grown up to millimeter size.

- Hydroxocobalamin is another vitamer of B12 commonly encountered in pharmacology, but is not normally present in the human body. Hydroxocobalamin is sometimes denoted B12a. This is the form of B12 produced by bacteria, and which is converted to cyanocobalmin in the commercial charcoal filtration step of production. Hydroxocobalamin has an avid affinity for cyanide ions and has been used as an antidote to cyanide poisoning. It is supplied typically in water solution for injection. Hydroxocobalamin is thought to be converted to the active enzymic forms of B12 more easily than cyanocobalamin, and since it is little more expensive than cyanocobalamin, and has longer retention times in the body, has been used for vitamin replacement in situations where added reassurance of activity is desired. Intramuscular administration of hydroxocobalamin is also the preferred treatment for pediatric patients with intrinsic cobalamin metabolic diseases, for vitamin B12 deficient patients with tobacco amblyopia (which is thought to perhaps have a component of cyanide poisoning from cyanide in cigarette smoke); and for treatment of patients with pernicious anemia who have optic neuropathy.

- Adenosylcobalamin (adoB12) and methylcobalamin (MeB12) are the two enzymatically active cofactor forms of B12 that naturally occur in the body. Most of the body's reserves are stored as adoB12 in the liver. These are converted to the other methylcobalamin form as needed.

Dietary recommendations

The U.S. Institute of Medicine (renamed National Academy of Medicine in 2015) updated Estimated Average Requirements (EARs) and Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for vitamin B12 in 1998. The EAR for vitamin B12

for women and men ages 14 and up is 2.0 μg/day; the RDA is 2.4 μg/day.

RDAs are higher than EARs so as to identify amounts that will cover

people with higher than average requirements. RDA for pregnancy equals

2.6 μg/day. RDA for lactation equals 2.8 μg/day. For infants up to 12

months the Adequate Intake (AI) is 0.4–0.5 μg/day. (AIs are established

when there is insufficient information to determine EARs and RDAs.) For

children ages 1–13 years the RDA increases with age from 0.9 to

1.8 μg/day. Because 10 to 30 percent of older people may be unable to

effectively absorb vitamin B12 naturally occurring in foods,

it is advisable for those older than 50 years to meet their RDA mainly

by consuming foods fortified with vitamin B12 or a supplement containing vitamin B12. As for safety, Tolerable Upper Intake Levels (known as ULs) are set for vitamins and minerals when evidence is sufficient. In the case of vitamin B12

there is no UL, as there is no human data for adverse effects from high

doses. Collectively the EARs, RDAs, AIs and ULs are referred to as Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs).

The European Food Safety Authority

(EFSA) refers to the collective set of information as Dietary Reference

Values, with Population Reference Intake (PRI) instead of RDA, and

Average Requirement instead of EAR. AI and UL defined the same as in

United States. For women and men over age 18 the Adequate Intake (AI) is

set at 4.0 μg/day. AI for pregnancy is 4.5 μg/day, for lactation

5.0 μg/day. For children aged 1–17 years the AIs increase with age from

1.5 to 3.5 μg/day. These AIs are higher than the U.S. RDAs.

The EFSA also reviewed the safety question and reached the same

conclusion as in United States - that there was not sufficient evidence

to set a UL for vitamin B12.

For U.S. food and dietary supplement labeling purposes the amount

in a serving is expressed as a percent of Daily Value (%DV). For

vitamin B12 labeling purposes 100% of the Daily Value was 6.0 μg, but as of May 27, 2016 was revised downward to 2.4 μg. A table of the old and new adult Daily Values is provided at Reference Daily Intake.

The original deadline to be in compliance was July 28, 2018, but on

September 29, 2017 the FDA released a proposed rule that extended the

deadline to January 1, 2020 for large companies and January 1, 2021 for

small companies.

Sources

Most omnivorous people in developed countries obtain enough vitamin B12 from consuming animal products including, meat, fish, eggs, and milk, but there are no vegan sources other than B12-fortified foods or B12 supplements.

Bacteria and archaea

B12 is only produced in nature by certain bacteria, and archaea. It is synthesized by some bacteria in the gut flora in humans and other animals, but humans cannot absorb this as it is made in the colon, downstream from the small intestine, where the absorption of most nutrients occurs. Ruminants, such as cows and sheep, absorb B12 produced by bacteria in their guts. For gut bacteria of ruminants to produce B12 the animal must consume sufficient amounts of cobalt. These grazing animals acquire the bacteria that produce vitamin B12, and the vitamin itself.

Feces are a rich source of vitamin B12, and are eaten by many animals, including dogs and cats. Lagomorpha species, including rabbits and hares, form fecal pellets in their cecum called cecotropes,

which consist of chewed plant material that has been metabolized by

cecal bacteria; cecotropes contain digestible carbohydrates and B

vitamins synthesized by the resident bacteria. These animals ingest

cecotropes which have been expelled in their feces.

Animals

Animals store vitamin B12 in liver and muscle and some pass the vitamin into their eggs and milk; meat, liver, eggs and milk are therefore sources of the vitamin for other animals as well as humans. For humans, the bioavailability from eggs is less than 9%, compared to 40% to 60% from fish, fowl and meat. Insects are a source of B12 for animals (including other insects and humans).

Food sources with a high concentration of vitamin B12—50 to 99 µg B12 per 100 grams of food—include clams; liver and other organ meats from lamb, veal, beef, and turkey; mackerel;

and crab meat.

Plants and algae

Natural sources of B12 include dried and fermented plant foods, such as tempeh, nori and laver, a seaweed. Many other types of algae are rich in vitamin B12, with some species, such as Porphyra yezoensis, containing as much cobalamin as liver.

Fortified foods

The UK Vegan Society, the Vegetarian Resource Group, and the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, among others, recommend that every vegan who is not consuming adequate B12 from fortified foods take supplements.

Foods for which B12-fortified versions are widely available include breakfast cereals, soy products, energy bars, and nutritional yeast.

Supplements

A blister pack of 500 µg methylcobalamin tablets

Vitamin B12 is included in multivitamin pills; and in some countries grain-based foods such as bread and pasta are fortified with B12. In the U.S. non-prescription products can be purchased providing up to 5,000 µg per serving, and it is a common ingredient in energy drinks and energy shots, usually at many times the recommended dietary allowance of B12.

The vitamin can also be a prescription product via injection or other

means. Tablets have sufficiently large quantities of the vitamin such

that 1% to 5% of the free crystalline B12 is absorbed along the entire intestine by passive diffusion.

Sublingual methylcobalamin, which contains no cyanide,

is available in 5-mg tablets. The metabolic fate and biological

distribution of methylcobalamin are expected to be similar to that of

other sources of vitamin B12 in the diet.,

but the amount of cyanide in cyanocobalamin even in the largest

available dose—20 µg of cyanide in a 1,000-µg cyanocobalamin tablet—is

less than the daily consumption of cyanide from food, and so

cyanocobalamin is not considered a health risk.

Parenteral administration

Injection

and patches are sometimes used if digestive absorption is impaired, but

this course of action may not be necessary with high-potency oral

supplements (such as 0.5–1 mg or more). Even pernicious anemia can be

treated entirely by the oral route.

If the person has inborn errors in the methyltransfer pathway (cobalamin C disease, combined methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria), treatment with intravenous, intramuscular hydroxocobalamin or transdermal B12 is needed.

Pseudovitamin-B12

Pseudovitamin-B12 refers to B12-like analogues that are biologically inactive in humans and yet found to be present alongside B12 in humans, many food sources (including animals), and possibly supplements and fortified foods. Most cyanobacteria, including Spirulina, and some algae, such as dried Asakusa-nori (Porphyra tenera), have been found to contain mostly pseudovitamin-B12 instead of biologically active B12. In one common form of pseudo-B12 available to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, the α-axial ligand is changed from dimethylbenzimidazole to adenine.

Biochemistry

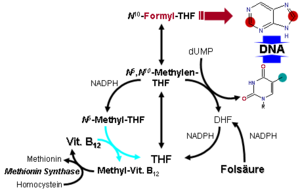

Metabolism of folic acid. The role of Vitamin B12 is seen at bottom-left.

Coenzyme function

Vitamin B12 functions as a coenzyme, meaning that its presence is required for enzyme-catalyzed reactions. Three types of enzymes:

- Isomerases

- Rearrangements in which a hydrogen atom is directly transferred between two adjacent atoms with concomitant exchange of the second substituent, X, which may be a carbon atom with substituents, an oxygen atom of an alcohol, or an amine. These use the adoB12 (adenosylcobalamin) form of the vitamin.

- Methyltransferases

- Methyl (–CH3) group transfers between two molecules. These use MeB12 (methylcobalamin) form of the vitamin.

- Dehalogenases

- Reactions in which a halogen atom is removed from an organic molecule. Enzymes in this class have not been identified in humans.

In humans, two major coenzyme B12-dependent enzyme

families corresponding to the first two reaction types, are known. These

are typified by the following two enzymes:

- MUT is an isomerase which uses the AdoB12 form and reaction type 1 to catalyze a carbon skeleton rearrangement (the X group is -COSCoA). MUT's reaction converts MMl-CoA to Su-CoA, an important step in the extraction of energy from proteins and fats. This functionality is lost in vitamin B12 deficiency, and can be measured clinically as an increased methylmalonic acid (MMA) level. Unfortunately, an elevated MMA is a sensitive but not specific test, and not all who have it actually have B12 deficiency. For example, MMA is elevated in 90–98% of patients with B12 deficiency; 20–25% of patients over the age of 70 have elevated levels of MMA, yet 25–33% of them do not have B12 deficiency. For this reason, assessment of MMA levels is not routinely recommended in the elderly. There is no "gold standard" test for B12 deficiency because as a B12 deficiency occurs, serum values may be maintained while tissue B12 stores become depleted. Therefore, serum B12 values above the cut-off point of deficiency do not necessarily indicate adequate B12 status. The MUT function is necessary for proper myelin synthesis and is not affected by folate supplementation.

- MTR, also known as methionine synthase, is a methyltransferase enzyme, which uses the MeB12 and reaction type 2 to transfer a methyl group from 5-methyltetrahydrofolate to homocysteine, thereby generating tetrahydrofolate (THF) and methionine.[52] This functionality is lost in vitamin B12 deficiency, resulting in an increased homocysteine level and the trapping of folate as 5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate, from which THF (the active form of folate) cannot be recovered. THF plays an important role in DNA synthesis so reduced availability of THF results in ineffective production of cells with rapid turnover, in particular red blood cells, and also intestinal wall cells which are responsible for absorption. THF may be regenerated via MTR or may be obtained from fresh folate in the diet. Thus all of the DNA synthetic effects of B12 deficiency, including the megaloblastic anemia of pernicious anemia, resolve if sufficient dietary folate is present. Thus the best-known "function" of B12 (that which is involved with DNA synthesis, cell-division, and anemia) is actually a facultative function which is mediated by B12-conservation of an active form of folate which is needed for efficient DNA production. Other cobalamin-requiring methyltransferase enzymes are also known in bacteria, such as Me-H4-MPT, coenzyme M methyltransferase.

Enzyme function

If folate is present in quantity, then of the two absolutely vitamin B12-dependent enzyme-family reactions in humans, the MUT-family

reactions show the most direct and characteristic secondary effects,

focusing on the nervous system (see below). This is because the MTR

(methyltransferase-type) reactions are involved in regenerating folate,

and thus are less evident when folate is in good supply.

Since the late 1990s, folic acid has begun to be added to fortify

flour in many countries, so folate deficiency is now more rare. At the

same time, since DNA synthetic-sensitive tests for anemia and erythrocyte

size are routinely done in even simple medical test clinics (so that

these folate-mediated biochemical effects are more often directly

detected), the MTR-dependent effects of B12

deficiency are becoming apparent not as anemia due to DNA-synthetic

problems (as they were classically), but now mainly as a simple and less

obvious elevation of homocysteine in the blood and urine (homocysteinuria).

This condition may result in long-term damage to arteries and in

clotting (stroke and heart attack), but this effect is difficult to

separate from other common processes associated with atherosclerosis and

aging.

The specific myelin damage resulting from B12

deficiency, even in the presence of adequate folate and methionine, is

more specifically and clearly a vitamin deficiency problem. It has been

connected to B12 most directly by reactions related to MUT,

which is absolutely required to convert methylmalonyl coenzyme A into

succinyl coenzyme A. Failure of this second reaction to occur results in

elevated levels of MMA, a myelin destabilizer. Excessive MMA will

prevent normal fatty acid synthesis, or it will be incorporated into fatty acids itself rather than normal malonic acid.

If this abnormal fatty acid subsequently is incorporated into myelin,

the resulting myelin will be too fragile, and demyelination will occur.

Although the precise mechanism or mechanisms are not known with

certainty, the result is subacute combined degeneration of spinal cord. Whatever the cause, it is known that B12 deficiency causes neuropathies, even if folic acid is present in good supply, and therefore anemia is not present.

Vitamin B12-dependent MTR reactions may also have neurological effects, through an indirect mechanism. Adequate methionine (which, like folate, must otherwise be obtained in the diet, if it is not regenerated from homocysteine by a B12 dependent reaction) is needed to make S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe), which is in turn necessary for methylation of myelin sheath phospholipids. Although production of SAMe is not B12 dependent, help in recycling for provision of one adequate substrate for it (the essential amino acid methionine) is assisted by B12. In addition, SAMe is involved in the manufacture of certain neurotransmitters, catecholamines

and in brain metabolism. These neurotransmitters are important for

maintaining mood, possibly explaining why depression is associated with B12

deficiency. Methylation of the myelin sheath phospholipids may also

depend on adequate folate, which in turn is dependent on MTR recycling,

unless ingested in relatively high amounts.

Physiology

Absorption

Methyl-B12 is absorbed by two processes. The first is an intestinal mechanism using intrinsic factor

through which 1–2 micrograms can be absorbed every few hours. The

second is a diffusion process by which approximately 1% of the remainder

is absorbed. The human physiology of vitamin B12 is complex, and therefore is prone to mishaps leading to vitamin B12 deficiency. Protein-bound vitamin B12 must be released from the proteins by the action of digestive proteases in both the stomach and small intestine. Gastric acid releases the vitamin from food particles; therefore antacid and acid-blocking medications (especially proton-pump inhibitors) may inhibit absorption of B12.

B12 taken in a low-solubility, non-chewable supplement

pill form may bypass the mouth and stomach and not mix with gastric

acids, but acids are not necessary for the absorption of free B12 not bound to protein; acid is necessary only to recover naturally-occurring vitamin B12 from foods.

R-protein (also known as haptocorrin and cobalophilin) is a B12 binding protein that is produced in the salivary glands. It must wait to bind food-B12 until B12 has been freed from proteins in food by pepsin in the stomach. B12 then binds to the R-protein to avoid degradation of it in the acidic environment of the stomach.

This pattern of B12 transfer to a special binding

protein secreted in a previous digestive step, is repeated once more

before absorption. The next binding protein for B12 is intrinsic factor (IF), a protein synthesized by gastric parietal cells that is secreted in response to histamine, gastrin and pentagastrin, as well as the presence of food.

In the duodenum, proteases digest R-proteins and release their bound B12, which then binds to IF, to form a complex (IF/B12). B12 must be attached to IF for it to be efficiently absorbed, as receptors on the enterocytes in the terminal ileum of the small bowel only recognize the B12-IF complex; in addition, intrinsic factor protects the vitamin from catabolism by intestinal bacteria.

Absorption of food vitamin B12 thus requires an intact and functioning stomach, exocrine pancreas, intrinsic factor, and small bowel. Problems with any one of these organs makes a vitamin B12 deficiency possible. Individuals who lack intrinsic factor have a decreased ability to absorb B12. In pernicious anemia, there is a lack of IF due to autoimmune atrophic gastritis,

in which antibodies form against parietal cells. Antibodies may

alternately form against and bind to IF, inhibiting it from carrying out

its B12 protective function. Due to the complexity of B12 absorption, geriatric patients, many of whom are hypoacidic due to reduced parietal cell function, have an increased risk of B12 deficiency.

This results in 80–100% excretion of oral doses in the feces versus

30–60% excretion in feces as seen in individuals with adequate IF.

Once the IF/B12 complex is recognized by specialized ileal receptors, it is transported into the portal circulation. The vitamin is then transferred to transcobalamin II (TC-II/B12),

which serves as the plasma transporter. Hereditary defects in

production of the transcobalamins and their receptors may produce

functional deficiencies in B12 and infantile megaloblastic anemia, and abnormal B12 related biochemistry, even in some cases with normal blood B12 levels. For the vitamin to serve inside cells, the TC-II/B12 complex must bind to a cell receptor, and be endocytosed. The transcobalamin-II is degraded within a lysosome, and free B12

is finally released into the cytoplasm, where it may be transformed

into the proper coenzyme, by certain cellular enzymes (see above).

Investigations into the intestinal absorption of B12

point out that the upper limit of absorption per single oral dose, under

normal conditions, is about 1.5 µg: "Studies in normal persons

indicated that about 1.5 µg is assimilated when a single dose varying

from 5 to 50 µg is administered by mouth. In a similar study Swendseid et al. stated that the average maximum absorption was 1.6 µg [...]" The bulk diffusion process of B12

absorption noted in the first paragraph above, may overwhelm the

complex R-factor and IGF-factor dependent absorption, when oral doses of

B12 are very large (a thousand or more µg per dose) as commonly happens in dedicated-pill oral B12 supplementation. It is this last fact which allows pernicious anemia and certain other defects in B12 absorption to be treated with oral megadoses of B12, even without any correction of the underlying absorption defects.

See the section on supplements above.

Storage and excretion

The total amount of vitamin B12

stored in body is about 2–5 mg in adults. Around 50% of this is stored

in the liver. Approximately 0.1% of this is lost per day by secretions

into the gut, as not all these secretions are reabsorbed. Bile is the

main form of B12 excretion; most of the B12 secreted in the bile is recycled via enterohepatic circulation. Excess B12

beyond the blood's binding capacity is typically excreted in urine.

Owing to the extremely efficient enterohepatic circulation of B12, the liver can store 3 to 5 years’ worth of vitamin B12; therefore, nutritional deficiency of this vitamin is rare. How fast B12 levels change depends on the balance between how much B12 is obtained from the diet, how much is secreted and how much is absorbed. B12

deficiency may arise in a year if initial stores are low and genetic

factors unfavourable, or may not appear for decades. In infants, B12 deficiency can appear much more quickly.

Deficiency

Vitamin B12 deficiency can potentially cause severe and irreversible damage, especially to the brain and nervous system. At levels only slightly lower than normal, a range of symptoms such as fatigue, lethargy, difficulty walking (staggering balance problems) depression, poor memory, breathlessness, headaches, and pale skin, among others, may be experienced, especially in elderly people (over age 60) who produce less stomach acid as they age, thereby increasing their probability of B12 deficiencies. Vitamin B12 deficiency can also cause symptoms of mania and psychosis.

Vitamin B12 deficiency is most commonly caused by low

intakes, but can also result from malabsorption, certain intestinal

disorders, low presence of binding proteins, and use of certain

medications. Vitamin B12 is rare from plant sources, so vegetarians are more likely to suffer from vitamin B12 deficiency. Infants are at a higher risk of vitamin B12

deficiency if they were born to vegetarian mothers. The elderly who

have diets with limited meat or animal products are vulnerable

populations as well. Vitamin B12 deficiency may occur in between 40% to 80% of the vegetarian population who are not also consuming a vitamin B12 supplement. In Hong Kong and India, vitamin B12

deficiency has been found in roughly 80% of the vegan population as

well. Vegans can avoid this by eating B12 fortified foods like cereals,

plant-based milks, and nutritional yeast as a regular part of their

diet.

In addition to worries concerning those following a vegetarian or vegan

diet, research has found that approximately 39 percent of the general

population may have possible B12 deficiencies or difficulty with the

absorption of this nutrient. Taking a B12 supplement could be beneficial

to most people.

B12 is a co-substrate of various cell reactions

involved in methylation synthesis of nucleic acid and neurotransmitters.

Synthesis of the trimonoamine neurotransmitters can enhance the effects

of a traditional antidepressant. The intracellular concentrations of vitamin B12

can be inferred through the total plasma concentration of homocysteine,

which can be converted to methionine through an enzymatic reaction that

uses 5-methyltetrahydrofolate as the methyl donor group. Consequently,

the plasma concentration of homocysteine falls as the intracellular

concentration of vitamin B12 rises. The active metabolite of vitamin B12

is required for the methylation of homocysteine in the production of

methionine, which is involved in a number of biochemical processes

including the monoamine neurotransmitters metabolism. Thus, a deficiency

in vitamin B12 may impact the production and function of those neurotransmitters.

Medical uses

Photograph of a vitamin B12

solution (hydroxycobalamin) in a multi-dose bottle, with a single dose

drawn up into a syringe for injection. Preparations are usually bright

red.

Repletion of deficiency

Severe vitamin B12

deficiency is corrected with frequent intramuscular injections of large

doses of the vitamin, followed by maintenance doses at longer

intervals. Tablets are sometimes used for repletion in mild deficiency;

and for maintenance regardless of severity. Vitamin B12 supplementation

sometimes leads to acne development.

Cyanide poisoning

For cyanide poisoning, a large amount of hydroxocobalamin may be given intravenously and sometimes in combination with sodium thiosulfate. The mechanism of action is straightforward: the hydroxycobalamin hydroxide ligand is displaced by the toxic cyanide ion, and the resulting harmless B12 complex is excreted in urine. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration approved the use of hydroxocobalamin for acute treatment of cyanide poisoning.

Drug interactions

H2-receptor antagonists and proton-pump inhibitors

Gastric acid is needed to release vitamin B12 from protein for absorption. Reduced secretion of gastric acid and pepsin produced by H2 blocker or proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) drugs can reduce absorption of protein-bound (dietary) vitamin B12, although not of supplemental vitamin B12. H2-receptor antagonist examples include cimetidine, famotidine, nizatidine, and ranitidine. PPIs examples include omeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole, pantoprazole, and esomeprazole. Clinically significant vitamin B12

deficiency and megaloblastic anemia are unlikely, unless these drug

therapies are prolonged for two or more years, or if in addition the

person's diet is below recommended intakes. Symptomatic vitamin

deficiency is more likely if the person is rendered achlorhydric (complete absence of gastric acid secretion), which occurs more frequently with proton pump inhibitors than H2 blockers.

Metformin

Reduced serum levels of vitamin B12 occur in up to 30% of people taking long-term anti-diabetic metformin. Deficiency does not develop if dietary intake of vitamin B12 is adequate or prophylactic B12 supplementation is given. If the deficiency is detected, metformin can be continued while the deficiency is corrected with B12 supplements.

Industrial production

Industrial production of B12 is achieved through fermentation of selected microorganisms. Streptomyces griseus, a bacterium once thought to be a fungus, was the commercial source of vitamin B12 for many years. The species Pseudomonas denitrificans and Propionibacterium freudenreichii subsp. shermanii are more commonly used today.

These are frequently grown under special conditions to enhance yield,

and at least one company uses genetically engineered versions of one or

both of these species. Since a number of species of Propionibacterium produce no exotoxins or endotoxins and are generally recognized as safe (have been granted GRAS status) by the Food and Drug Administration of the United States, they are presently the FDA-preferred bacterial fermentation organisms for vitamin B12 production.

The total world production of vitamin B12, by four companies (the French Sanofi-Aventis and three Chinese companies) in 2008 was 35 tonnes.

Laboratory synthesis

No eukaryotic organisms (including plants, animals, and fungi) are independently capable of constructing vitamin B12. Only bacteria and archaea have the enzymes required for its biosynthesis. Like all tetrapyrroles, it is derived from uroporphyrinogen III. This porphyrinogen is methylated at two pyrrole rings to give dihydrosirohydrochlorin, which is oxidized to sirohydrochlorin, which undergoes further reactions, notably a ring contraction, to give the corrin ring.

The complete laboratory synthesis of B12 was achieved by Robert Burns Woodward and Albert Eschenmoser in 1972,

and remains one of the classic feats of organic synthesis, requiring

the effort of 91 postdoctoral fellows (mostly at Harvard) and 12 PhD

students (at ETH Zurich)

from 19 nations. The synthesis constitutes a formal total synthesis,

since the research groups only prepared the known intermediate cobyric

acid, whose chemical conversion to vitamin B12 was previously

reported. Though it constitutes an intellectual achievement of the

highest caliber, the Eschenmoser–Woodward synthesis of vitamin B12

is of no practical consequence due to its length, taking 72 chemical

steps and giving an overall chemical yield well under 0.01%. And although there have been sporadic synthetic efforts since 1972,

the Eschenmoser–Woodward synthesis remains the only completed (formal)

total synthesis. Bacterial (or, perhaps archaeal) fermentation remains

the only industrially viable source of the vitamin for food production

and medicine.

Species from the following genera and species are known to synthesize B12: Propionibacterium shermanii, Pseudomonas denitrificans, Streptomyces griseus, Acetobacterium, Aerobacter, Agrobacterium, Alcaligenes, Azotobacter, Bacillus, Clostridium, Corynebacterium, Flavobacterium, Lactobacillus, Micromonospora, Mycobacterium, Nocardia, Protaminobacter, Proteus,

Rhizobium, Salmonella, Serratia, Streptococcus and Xanthomonas.

History

- 1849 - Thomas Addison first described a case of pernicious anemia.

- 1877 - William Osler and William Gardner first described a case of neuropathy in this condition.

- 1878 - Hayem first described large red cells in the peripheral blood in this condition, which he called "giant blood corpuscles", now called macrocytes.

- 1880 - Paul Ehrlich first identified megaloblasts in the bone marrow in this condition.

- 1887 - Ludwig Lichtheim first described a case of myopathy in this condition.

- 1920 - George Whipple discovered that ingesting large amounts of liver seemed to most rapidly cure the anemia of blood loss in dogs, and hypothesized that eating liver might treat pernicious anemia.

- 1926 - George Minot shared the 1934 Nobel Prize with William Murphy and George Whipple, for discovery of an effective treatment for pernicious anemia using liver concentrate, later found to contain a large amount of vitamin B12.

- 1928 - Edwin Cohn prepared a liver extract that was 50 to 100 times more potent in treating pernicious anema than the natural liver products. Whipple, Minot, and Murphy shared the 1934 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

- 1929 - William Castle demonstrated that gastric juice contained an "intrinsic factor" which when combined with meat ingestion resulted in absorption of the vitamin in this condition.

- 1947 - Mary Shaw Shorb, in a collaborative project with Karl Folkers, was provided with a US$400 grant to develop the so-called "LLD assay" for B12. LLD stood for Lactobacillus lactis Dorner, a strain of bacterium which required "LLD factor" for growth, which was eventually identified as B12.

- 1948 - Shorb and colleagues Karl A. Folkers and Alexander R. Todd used the LLD assay to rapidly extract the anti-pernicious anemia factor from liver extracts, and pure B12 was isolated.

- 1949 - Shorb and Folkers received the Mead Johnson Award from the American Society of Nutritional Sciences for their discovery.

- 1956 - The chemical structure of the molecule was determined by Dorothy Hodgkin, based on crystallographic data. She was awarded the 1964 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for determining the structure of vitamin B12 and other complex molecules.

- 1959 - methods of producing the vitamin in large quantities from bacteria cultures were developed.

- 1981 - Observations of stereospecificity encountered by R. B. Woodward during the synthesis of vitamin B12 led to the formulation of the principle of the conservation of orbital symmetry, which would result in a Nobel Prize in Chemistry by R. Hoffmann and K. Fukui.

Six Nobel Prizes have been awarded for direct and indirect studies of vitamin B12.