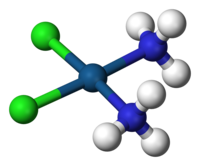

In chemistry, a coordination complex consists of a central atom or ion, which is usually metallic and is called the coordination centre, and a surrounding array of bound molecules or ions, that are in turn known as ligands or complexing agents. Many metal-containing compounds, especially those of transition metals, are coordination complexes. A coordination complex whose centre is a metal atom is called a metal complex.

Nomenclature and terminology

Coordination

complexes are so pervasive that their structures and reactions are

described in many ways, sometimes confusingly. The atom within a ligand

that is bonded to the central metal atom or ion is called the donor atom. In a typical complex, a metal ion is bonded to several donor atoms, which can be the same or different. A polydentate

(multiple bonded) ligand is a molecule or ion that bonds to the central

atom through several of the ligand's atoms; ligands with 2, 3, 4 or

even 6 bonds to the central atom are common. These complexes are called chelate complexes; the formation of such complexes is called chelation, complexation, and coordination.

The central atom or ion, together with all ligands, comprise the coordination sphere. The central atoms or ion and the donor atoms comprise the first coordination sphere.

Coordination refers to the "coordinate covalent bonds" (dipolar bonds) between the ligands and the central atom. Originally, a complex implied a reversible association of molecules, atoms, or ions through such weak chemical bonds.

As applied to coordination chemistry, this meaning has evolved. Some

metal complexes are formed virtually irreversibly and many are bound

together by bonds that are quite strong.

The number of donor atoms attached to the central atom or ion is called the coordination number.

The most common coordination numbers are 2, 4, and especially 6. A

hydrated ion is one kind of a complex ion (or simply a complex), a

species formed between a central metal ion and one or more surrounding

ligands, molecules or ions that contain at least one lone pair of

electrons.

If all the ligands are monodentate,

then the number of donor atoms equals the number of ligands. For

example, the cobalt(II) hexahydrate ion or the hexaaquacobalt(II) ion

[Co(H2O)6]2+ is a hydrated-complex ion

that consists of six water molecules attached to a metal ion Co. The

oxidation state and the coordination number reflect the number of bonds

formed between the metal ion and the ligands in the complex ion.

However, the coordination number of Pt(en)2+

2 is 4 (rather than 2) since it has two bidentate ligands, which contain four donor atoms in total.

2 is 4 (rather than 2) since it has two bidentate ligands, which contain four donor atoms in total.

Any donor atom will give a pair of electrons. There are some

donor atoms or groups which can offer more than one pair of electrons.

Such are called bidentate (offers two pairs of electrons) or polydentate

(offers more than two pairs of electrons). In some cases an atom or a

group offers a pair of electrons to two similar or different central

metal atoms or acceptors—by division of the electron pair—into a three-center two-electron bond. These are called bridging ligands.

History

Coordination

complexes have been known since the beginning of modern chemistry.

Early well-known coordination complexes include dyes such as Prussian blue. Their properties were first well understood in the late 1800s, following the 1869 work of Christian Wilhelm Blomstrand.

Blomstrand developed what has come to be known as the complex ion chain

theory. The theory claimed that the reason coordination complexes form

is because in solution, ions would be bound via ammonia chains. He

compared this effect to the way that various carbohydrate chains form.

Following this theory, Danish scientist Sophus Mads Jørgensen

made improvements to it. In his version of the theory, Jørgensen

claimed that when a molecule dissociates in a solution there were two

possible outcomes: the ions would bind via the ammonia chains Blomstrand

had described or the ions would bind directly to the metal.

It was not until 1893 that the most widely accepted version of the theory today was published by Alfred Werner.

Werner’s work included two important changes to the Blomstrand theory.

The first was that Werner described the two different ion possibilities

in terms of location in the coordination sphere. He claimed that if the

ions were to form a chain this would occur outside of the coordination

sphere while the ions that bound directly to the metal would do so

within the coordination sphere.

In one of Werner’s most important discoveries however he disproved the

majority of the chain theory. Werner was able to discover the spatial

arrangements of the ligands that were involved in the formation of the

complex hexacoordinate cobalt. His theory allows one to understand the

difference between a coordinated ligand and a charge balancing ion in a

compound, for example the chloride ion in the cobaltammine chlorides and

to explain many of the previously inexplicable isomers.

Structure of hexol

In 1914, Werner first resolved the coordination complex, called hexol, into optical isomers, overthrowing the theory that only carbon compounds could possess chirality.

Structures

The ions or molecules surrounding the central atom are called ligands. Ligands are generally bound to the central atom by a coordinate covalent bond (donating electrons from a lone electron pair into an empty metal orbital), and are said to be coordinated to the atom. There are also organic ligands such as alkenes whose pi bonds can coordinate to empty metal orbitals. An example is ethene in the complex known as Zeise's salt, K+[PtCl3(C2H4)]−.

Geometry

In coordination chemistry, a structure is first described by its coordination number,

the number of ligands attached to the metal (more specifically, the

number of donor atoms). Usually one can count the ligands attached, but

sometimes even the counting can become ambiguous. Coordination numbers

are normally between two and nine, but large numbers of ligands are not

uncommon for the lanthanides and actinides. The number of bonds depends

on the size, charge, and electron configuration of the metal ion and the ligands. Metal ions may have more than one coordination number.

Typically the chemistry of transition metal complexes is dominated by interactions between s and p molecular orbitals

of the donor-atoms in the ligands and the d orbitals of the metal ions.

The s, p, and d orbitals of the metal can accommodate 18 electrons.

The maximum coordination number for a certain metal is thus related to

the electronic configuration of the metal ion (to be more specific, the

number of empty orbitals) and to the ratio of the size of the ligands

and the metal ion. Large metals and small ligands lead to high

coordination numbers, e.g. [Mo(CN)8]4−. Small metals with large ligands lead to low coordination numbers, e.g. Pt[P(CMe3)]2. Due to their large size, lanthanides, actinides, and early transition metals tend to have high coordination numbers.

Different ligand structural arrangements result from the

coordination number. Most structures follow the points-on-a-sphere

pattern (or, as if the central atom were in the middle of a polyhedron

where the corners of that shape are the locations of the ligands),

where orbital overlap (between ligand and metal orbitals) and

ligand-ligand repulsions tend to lead to certain regular geometries. The

most observed geometries are listed below, but there are many cases

that deviate from a regular geometry, e.g. due to the use of ligands of

different types (which results in irregular bond lengths; the

coordination atoms do not follow a points-on-a-sphere pattern), due to

the size of ligands, or due to electronic effects:

- Linear for two-coordination

- Trigonal planar for three-coordination

- Tetrahedral or square planar for four-coordination

- Trigonal bipyramidal for five-coordination

- Octahedral for six-coordination

- Pentagonal bipyramidal for seven-coordination

- Square antiprismatic for eight-coordination

- Tricapped trigonal prismatic for nine-coordination

The idealized descriptions of 5-, 7-, 8-, and 9- coordination are

often indistinct geometrically from alternative structures with slightly

different L-M-L (ligand-metal-ligand) angles, e.g. the difference

between square pyramidal and trigonal bipyramidal structures.

- Square pyramidal for five-coordination

- Capped octahedral or capped trigonal prismatic for seven-coordination

- Dodecahedral or bicapped trigonal prismatic for eight-coordination

- Capped square antiprismatic for nine-coordination

In systems with low d electron count, due to special electronic effects such as (second-order) Jahn–Teller stabilization,

certain geometries (in which the coordination atoms do not follow a

points-on-a-sphere pattern) are stabilized relative to the other

possibilities, e.g. for some compounds the trigonal prismatic geometry

is stabilized relative to octahedral structures for six-coordination.

- Bent for two-coordination

- Trigonal pyramidal for three-coordination

- Trigonal prismatic for six-coordination

Isomerism

The

arrangement of the ligands is fixed for a given complex, but in some

cases it is mutable by a reaction that forms another stable isomer.

There exist many kinds of isomerism in coordination complexes, just as in many other compounds.

Stereoisomerism

Stereoisomerism occurs with the same bonds in different orientations relative to one another. Stereoisomerism can be further classified into:

Cis–trans isomerism and facial–meridional isomerism

Cis–trans isomerism occurs in octahedral and square planar complexes (but not tetrahedral). When two ligands are adjacent they are said to be cis, when

opposite each other, trans. When three identical ligands occupy one face of an octahedron, the isomer is said to be facial, or fac. In a fac isomer, any two identical ligands are adjacent or cis to each other. If these three ligands and the metal ion are in one plane, the isomer is said to be meridional, or mer. A mer isomer can be considered as a combination of a trans and a cis, since it contains both trans and cis pairs of identical ligands.

Optical isomerism

Optical isomerism occurs when a molecule is not superimposable with its mirror image. It is so called because the two isomers are each optically active, that is, they rotate the plane of polarized light in opposite directions. The symbol Λ (lambda)

is used as a prefix to describe the left-handed propeller twist formed

by three bidentate ligands, as shown. Likewise, the symbol Δ (delta) is used as a prefix for the right-handed propeller twist.

Structural isomerism

Structural isomerism

occurs when the bonds are themselves different. There are four types of

structural isomerism: ionisation isomerism, solvate or hydrate

isomerism, linkage isomerism and coordination isomerism.

- Ionisation isomerism – the isomers give different ions in solution although they have the same composition. This type of isomerism occurs when the counter ion of the complex is also a potential ligand. For example, pentaamminebromocobalt(III) sulphate [Co(NH3)5Br]SO4 is red violet and in solution gives a precipitate with barium chloride, confirming the presence of sulphate ion, while pentaamminesulphatecobalt(III) bromide [Co(NH3)5SO4]Br is red and tests negative for sulphate ion in solution, but instead gives a precipitate of AgBr with silver nitrate.

- Solvate or hydrate isomerism – the isomers have the same composition but differ with respect to the number of molecules of solvent that serve as ligand vs simply occupying sites in the crystal. Examples: [Cr(H2O)6]Cl3 is violet colored, [CrCl(H2O)5]Cl2·H2O is blue-green, and [CrCl2(H2O)4]Cl·2H2O is dark green. See water of crystallization.

- Linkage isomerism occurs with ambidentate ligands that can bind in more than one place. For example, NO2 is an ambidentate ligand: It can bind to a metal at either the N atom or an O atom.

- Coordination isomerism – this occurs when both positive and negative ions of a salt are complex ions and the two isomers differ in the distribution of ligands between the cation and the anion. For example, [Co(NH3)6][Cr(CN)6] and [Cr(NH3)6][Co(CN)6].

Electronic properties

Many

of the properties of transition metal complexes are dictated by their

electronic structures. The electronic structure can be described by a

relatively ionic model that ascribes formal charges to the metals and

ligands. This approach is the essence of crystal field theory (CFT). Crystal field theory, introduced by Hans Bethe in 1929, gives a quantum mechanically

based attempt at understanding complexes. But crystal field theory

treats all interactions in a complex as ionic and assumes that the

ligands can be approximated by negative point charges.

More sophisticated models embrace covalency, and this approach is described by ligand field theory (LFT) and Molecular orbital theory

(MO). Ligand field theory, introduced in 1935 and built from molecular

orbital theory, can handle a broader range of complexes and can explain

complexes in which the interactions are covalent. The chemical applications of group theory

can aid in the understanding of crystal or ligand field theory, by

allowing simple, symmetry based solutions to the formal equations.

Chemists tend to employ the simplest model required to predict

the properties of interest; for this reason, CFT has been a favorite for

the discussions when possible. MO and LF theories are more complicated,

but provide a more realistic perspective.

The electronic configuration of the complexes gives them some important properties:

Color of transition metal complexes

Synthesis of copper(II)-tetraphenylporphyrin, a metal complex, from tetraphenylporphyrin and copper(II) acetate monohydrate.

Transition metal complexes often have spectacular colors caused by

electronic transitions by the absorption of light. For this reason they

are often applied as pigments. Most transitions that are related to colored metal complexes are either d–d transitions or charge transfer bands.

In a d–d transition, an electron in a d orbital on the metal is

excited by a photon to another d orbital of higher energy, therefore d–d

transitions occur only for partially-filled d-orbital complexes (d1–9). For complexes having d0 or d10

configuration, charge transfer is still possible even though d–d

transitions are not. A charge transfer band entails promotion of an

electron from a metal-based orbital into an empty ligand-based orbital (metal-to-ligand charge transfer or MLCT). The converse also occurs: excitation of an electron in a ligand-based orbital into an empty metal-based orbital (ligand-to-metal charge transfer or LMCT). These phenomena can be observed with the aid of electronic spectroscopy; also known as UV-Vis. For simple compounds with high symmetry, the d–d transitions can be assigned using Tanabe–Sugano diagrams. These assignments are gaining increased support with computational chemistry.

Colors of lanthanide complexes

Superficially lanthanide complexes are similar to those of the transition metals in that some are coloured. However, for the common Ln3+

ions (Ln = lanthanide) the colors are all pale, and hardly influenced

by the nature of the ligand. The colors are due to 4f electron

transitions. As the 4f orbitals in lanthanides are “buried” in the xenon

core and shielded from the ligand by the 5s and 5p orbitals they are

therefore not influenced by the ligands to any great extent leading to a

much smaller crystal field splitting than in the transition metals. The absorption spectra of an Ln3+ ion approximates to that of the free ion where the electronic states are described by spin-orbit coupling. This contrasts to the transition metals where the ground state is split by the crystal field. Absorptions for Ln3+ are weak as electric dipole transitions are parity forbidden (Laporte Rule forbidden) but can gain intensity due to the effect of a low-symmetry ligand field or mixing with higher electronic states (e.g.

d orbitals). Also absorption bands are extremely sharp which contrasts

with those observed for transition metals which generally have broad

bands. This can lead to extremely unusual effects, such as significant color changes under different forms of lighting.

Magnetism

Metal complexes that have unpaired electrons are magnetic.

Considering only monometallic complexes, unpaired electrons arise

because the complex has an odd number of electrons or because electron

pairing is destabilized. Thus, monomeric Ti(III) species have one

"d-electron" and must be (para)magnetic,

regardless of the geometry or the nature of the ligands. Ti(II), with

two d-electrons, forms some complexes that have two unpaired electrons

and others with none. This effect is illustrated by the compounds TiX2[(CH3)2PCH2CH2P(CH3)2]2: when X = Cl, the complex is paramagnetic (high-spin configuration), whereas when X = CH3, it is diamagnetic (low-spin configuration). It is important to realize that ligands provide an important means of adjusting the ground state properties.

In bi- and polymetallic complexes, in which the individual

centres have an odd number of electrons or that are high-spin, the

situation is more complicated. If there is interaction (either direct

or through ligand) between the two (or more) metal centres, the

electrons may couple (antiferromagnetic coupling, resulting in a diamagnetic compound), or they may enhance each other (ferromagnetic coupling). When there is no interaction, the two (or more) individual metal centers behave as if in two separate molecules.

Reactivity

Complexes show a variety of possible reactivities:

- Electron transfers

- A common reaction between coordination complexes involving ligands are inner and outer sphere electron transfers. They are two different mechanisms of electron transfer redox reactions, largely defined by the late Henry Taube. In an inner sphere reaction, a ligand with two lone electron pairs acts as a bridging ligand, a ligand to which both coordination centres can bond. Through this, electrons are transferred from one centre to another.

- (Degenerate) ligand exchange

- One important indicator of reactivity is the rate of degenerate exchange of ligands. For example, the rate of interchange of coordinate water in [M(H2O)6]n+ complexes varies over 20 orders of magnitude. Complexes where the ligands are released and rebound rapidly are classified as labile. Such labile complexes can be quite stable thermodynamically. Typical labile metal complexes either have low-charge (Na+), electrons in d-orbitals that are antibonding with respect to the ligands (Zn2+), or lack covalency (Ln3+, where Ln is any lanthanide). The lability of a metal complex also depends on the high-spin vs. low-spin configurations when such is possible. Thus, high-spin Fe(II) and Co(III) form labile complexes, whereas low-spin analogues are inert. Cr(III) can exist only in the low-spin state (quartet), which is inert because of its high formal oxidation state, absence of electrons in orbitals that are M–L antibonding, plus some "ligand field stabilization" associated with the d3 configuration.

- Associative processes

- Complexes that have unfilled or half-filled orbitals often show the capability to react with substrates. Most substrates have a singlet ground-state; that is, they have lone electron pairs (e.g., water, amines, ethers), so these substrates need an empty orbital to be able to react with a metal centre. Some substrates (e.g., molecular oxygen) have a triplet ground state, which results that metals with half-filled orbitals have a tendency to react with such substrates (it must be said that the dioxygen molecule also has lone pairs, so it is also capable to react as a 'normal' Lewis base).

If the ligands around the metal are carefully chosen, the metal can aid in (stoichiometric or catalytic) transformations of molecules or be used as a sensor.

Classification

Metal complexes, also known as coordination compounds, include all metal compounds, aside from metal vapors, plasmas, and alloys. The study of "coordination chemistry" is the study of "inorganic chemistry" of all alkali and alkaline earth metals, transition metals, lanthanides, actinides, and metalloids.

Thus, coordination chemistry is the chemistry of the majority of the

periodic table. Metals and metal ions exist, in the condensed phases at

least, only surrounded by ligands.

The areas of coordination chemistry can be classified according to the nature of the ligands, in broad terms:

- Classical (or "Werner Complexes"): Ligands in classical coordination chemistry bind to metals, almost exclusively, via their lone pairs of electrons residing on the main-group atoms of the ligand. Typical ligands are H2O, NH3, Cl−, CN−, en. Some of the simplest members of such complexes are described in metal aquo complexes, metal ammine complexes,

- Examples: [Co(EDTA)]−, [Co(NH3)6]Cl3, [Fe(C2O4)3]K3

- Organometallic Chemistry: Ligands are organic (alkenes, alkynes, alkyls) as well as "organic-like" ligands such as phosphines, hydride, and CO.

- Example: (C5H5)Fe(CO)2CH3

- Bioinorganic Chemistry: Ligands are those provided by nature, especially including the side chains of amino acids, and many cofactors such as porphyrins.

- Example: hemoglobin contains heme, a porphyrin complex of iron

- Example: chlorophyll contains a porphyrin complex of magnesium

- Many natural ligands are "classical" especially including water.

- Cluster Chemistry: Ligands are all of the above also include other metals as ligands.

- Example Ru3(CO)12

- In some cases there are combinations of different fields:

- Example: [Fe4S4(Scysteinyl)4]2−, in which a cluster is embedded in a biologically active species.

Mineralogy, materials science, and solid state chemistry –

as they apply to metal ions – are subsets of coordination chemistry in

the sense that the metals are surrounded by ligands. In many cases

these ligands are oxides or sulfides, but the metals are coordinated

nonetheless, and the principles and guidelines discussed below apply. In

hydrates,

at least some of the ligands are water molecules. It is true that the

focus of mineralogy, materials science, and solid state chemistry

differs from the usual focus of coordination or inorganic chemistry. The

former are concerned primarily with polymeric structures, properties

arising from a collective effects of many highly interconnected metals.

In contrast, coordination chemistry focuses on reactivity and properties

of complexes containing individual metal atoms or small ensembles of

metal atoms.

Nomenclature of Coordination complexes

The basic procedure for naming a complex:

- When naming a complex ion, the ligands are named before the metal ion.

- Write the names of the ligands in alphabetical order. (Numerical prefixes do not affect the order.)

- Multiple occurring monodentate ligands receive a prefix according to the number of occurrences: di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, or hexa. Polydentate ligands (e.g., ethylenediamine, oxalate) receive bis-, tris-, tetrakis-, etc.

- Anions end in o. This replaces the final 'e' when the anion ends with '-ide', '-ate' or '-ite', e.g. chloride becomes chlorido and sulfate becomes sulfato. Formerly, '-ide' was changed to '-o' (e.g. chloro and cyano), but this rule has been modified in the 2005 IUPAC recommendations and the correct forms for these ligands are now chlorido and cyanido.

- Neutral ligands are given their usual name, with some exceptions: NH3 becomes ammine; H2O becomes aqua or aquo; CO becomes carbonyl; NO becomes nitrosyl.

- Write the name of the central atom/ion. If the complex is an anion, the central atom's name will end in -ate, and its Latin name will be used if available (except for mercury).

- The oxidation state of the central atom is to be specified (when it is one of several possible, or zero), and should be written as a Roman numeral (or 0) enclosed in parentheses.

- Name of the cation should be preceded by the name of anion. (if applicable, as in last example)

Examples:

| metal | changed to |

|---|---|

| cobalt | cobaltate |

| aluminium | aluminate |

| chromium | chromate |

| vanadium | vanadate |

| copper | cuprate |

| iron | ferrate |

- [Cu(H2O)6] 2+ → hexaaquacopper(II) ion

- [NiCl4]2− → tetrachloridonickelate(II) ion (The use of chloro- was removed from IUPAC naming convention)

- [CuCl5NH3]3− → amminepentachloridocuprate(II) ion

- [Cd(CN)2(en)2] → dicyanidobis(ethylenediamine)cadmium(II)

- [CoCl(NH3)5]SO4 → pentaamminechloridocobalt(III) sulfate

- K4[Fe(CN)6] → potassium hexacyanidoferrate(II)

The coordination number of ligands attached to more than one metal

(bridging ligands) is indicated by a subscript to the Greek symbol μ placed before the ligand name. Thus the dimer of aluminium trichloride is described by Al2Cl4(μ2-Cl)2.

Any anionic group can be electronically stabilized by any cation.

An anionic complex can be stabilised by a hydrogen cation, becoming an

acidic complex which can dissociate to release the cationic hydrogen.

This kind of complex compound has a name with "ic" added after the

central metal. For example, H2[Pt(CN)4] has the name tetracyanoplatinic (II) acid.

Stability constant

The affinity of metal ions for ligands is described by a stability

constant, also called the formation constant, and is represented by the

symbol Kf. It is the equilibrium constant

for its assembly from the constituent metal and ligands, and can be

calculated accordingly, as in the following example for a simple case:

- (X)Metal(aq) + (Y)Lewis Base(aq) ⇌ (Z)Complex Ion(aq)

where X, Y, and Z are the stoichiometric

coefficients of each species. Formation constants vary widely. Large

values indicate that the metal has high affinity for the ligand,

provided the system is at equilibrium.

Sometimes the stability constant will be in a different form

known as the constant of destability. This constant is expressed as the

inverse of the constant of formation and is denoted as Kd = 1/Kf .

This constant represents the reverse reaction for the decomposition of a

complex ion into its individual metal and ligand components. When

comparing the values for Kd, the larger the value is the more unstable the complex ion is.

As a result of these complex ions forming in solutions they also

can play a key role in solubility of other compounds. When a complex ion

is formed it can alter the concentrations of its components in the

solution. For example:

- Ag+

(aq) + 2NH4OH(aq) ⇌ Ag(NH3)+

2 + H2O

- AgCl(s) + H2O(l) ⇌ Ag+

(aq) + Cl−

(aq)

If these reactions both occurred in the same reaction vessel, the

solubility of the silver chloride would be increased by the presence of

NH4OH because formation of the silver(I)–ammine complex

consumes a significant portion of the free silver ions from the

solution. By Le Chatelier's principle,

this causes the equilibrium reaction for the dissolving of the silver

chloride, which has silver ion as a product, to shift to the right.

This new solubility can be calculated given the values of Kf and Ksp

for the original reactions. The solubility is found essentially by

combining the two separate equilibria into one combined equilibrium

reaction and this combined reaction is the one that determines the new

solubility. So Kc, the new solubility constant, is denoted by:

Application of coordination compounds

Metals

only exist in solution as coordination complexes, it follows then that

this class of compounds is useful in a wide variety of ways.

Bioinorganic chemistry

In bioinorganic chemistry and bioorganometallic chemistry,

coordination complexes serve either structural or catalytic functions.

An estimated 30% of proteins contain metal ions. Examples include the

intensely colored vitamin B12, the heme group in hemoglobin, the cytochromes, the chlorin group in chlorophyll, and carboxypeptidase, a hydrolytic enzyme important in digestion. Another complex ion enzyme is catalase, which decomposes the cell's waste hydrogen peroxide.

Industry

Homogeneous catalysis is a major application of coordination compounds for the production of organic substances. Processes include hydrogenation, hydroformylation, oxidation. In one example, a combination of titanium trichloride and triethylaluminium gives rise to Ziegler–Natta catalysts, used for the polymerization of ethylene and propylene to give polymers of great commercial importance as fibers, films, and plastics.

Nickel, cobalt, and copper can be extracted using hydrometallurgical processes involving complex ions. They are extracted from their ores as ammine

complexes. Metals can also be separated using the selective

precipitation and solubility of complex ions. Cyanide is used chiefly

for extraction of gold and silver from their ores.

Phthalocyanine complexes are an important class of pigments.

Analysis

At one time, coordination compounds were used to identify the presence of metals in a sample. Qualitative inorganic analysis has largely been superseded by instrumental methods of analysis such as atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS), inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS).

![{\displaystyle K_{f}={\frac {[{\text{Complex ion}}]^{Z}}{[{\text{Metal ion}}]^{X}[{\text{Lewis base}}]^{Y}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f4126a8afae00c2b0773a00eea6e33c27517b0b2)