| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Curium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈkjʊəriəm/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

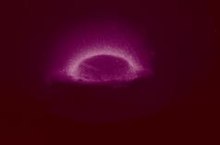

| Appearance | silvery metallic, glows purple in the dark | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mass number | 247 (most stable isotope) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Curium in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 96 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group n/a | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | f-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | actinide | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Rn] 5f7 6d1 7s2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Electrons per shell

| 2, 8, 18, 32, 25, 9, 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1613 K (1340 °C, 2444 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 3383 K (3110 °C, 5630 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 13.51 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 13.85 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | +2, +3, +4, +5, +6, (an amphoteric oxide) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 174 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 169±3 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spectral lines of curium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | synthetic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | double hexagonal close-packed (dhcp) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 1.25 µΩ·m | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | antiferromagnetic-paramagnetic transition at 52 K | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-51-9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | named after Marie Skłodowska-Curie and Pierre Curie | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

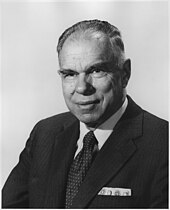

| Discovery | Glenn T. Seaborg, Ralph A. James, Albert Ghiorso (1944) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main isotopes of curium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Curium is a transuranic radioactive chemical element with symbol Cm and atomic number 96. This element of the actinide series was named after Marie and Pierre Curie – both were known for their research on radioactivity. Curium was first intentionally produced and identified in July 1944 by the group of Glenn T. Seaborg at the University of California, Berkeley. The discovery was kept secret and only released to the public in November 1947. Most curium is produced by bombarding uranium or plutonium with neutrons in nuclear reactors – one tonne of spent nuclear fuel contains about 20 grams of curium.

Curium is a hard, dense, silvery metal with a relatively high melting point and boiling point for an actinide. Whereas it is paramagnetic at ambient conditions, it becomes antiferromagnetic upon cooling, and other magnetic transitions are also observed for many curium compounds. In compounds, curium usually exhibits valence +3 and sometimes +4, and the +3 valence is predominant in solutions. Curium readily oxidizes, and its oxides are a dominant form of this element. It forms strongly fluorescent complexes with various organic compounds, but there is no evidence of its incorporation into bacteria and archaea. When introduced into the human body, curium accumulates in the bones, lungs and liver, where it promotes cancer.

All known isotopes of curium are radioactive and have a small critical mass for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. They predominantly emit α-particles, and the heat released in this process can serve as a heat source in radioisotope thermoelectric generators, but this application is hindered by the scarcity and high cost of curium isotopes. Curium is used in production of heavier actinides and of the 238Pu radionuclide for power sources in artificial pacemakers. It served as the α-source in the alpha particle X-ray spectrometers installed on several space probes, including the Sojourner, Spirit, Opportunity and Curiosity Mars rovers and the Philae lander on comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, to analyze the composition and structure of the surface.

History

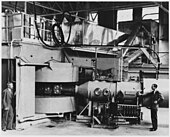

The 60-inch (150 cm) cyclotron at the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, in August 1939.

Although curium had likely been produced in previous nuclear experiments, it was first intentionally synthesized, isolated and identified in 1944, at the University of California, Berkeley, by Glenn T. Seaborg, Ralph A. James, and Albert Ghiorso. In their experiments, they used a 60-inch (150 cm) cyclotron.

Curium was chemically identified at the Metallurgical Laboratory (now Argonne National Laboratory) at the University of Chicago. It was the third transuranium element to be discovered even though it is the fourth in the series – the lighter element americium was unknown at the time.

The sample was prepared as follows: first plutonium nitrate solution was coated on a platinum foil of about 0.5 cm2 area, the solution was evaporated and the residue was converted into plutonium(IV) oxide (PuO2) by annealing. Following cyclotron irradiation of the oxide, the coating was dissolved with nitric acid and then precipitated as the hydroxide using concentrated aqueous ammonia solution. The residue was dissolved in perchloric acid, and further separation was carried out by ion exchange

to yield a certain isotope of curium. The separation of curium and

americium was so painstaking that the Berkeley group initially called

those elements pandemonium (from Greek for all demons or hell) and delirium (from Latin for madness).

The curium-242 isotope was produced in July–August 1944 by bombarding 239Pu with α-particles to produce curium with the release of a neutron:

Curium-242 was unambiguously identified by the characteristic energy of the α-particles emitted during the decay:

The half-life of this alpha decay was first measured as 150 days and then corrected to 162.8 days.

Another isotope 240Cm was produced in a similar reaction in March 1945:

The half-life of the 240Cm α-decay was correctly determined as 26.7 days.

The discovery of curium, as well as americium, in 1944 was closely related to the Manhattan Project,

so the results were confidential and declassified only in 1945. Seaborg

leaked the synthesis of the elements 95 and 96 on the U.S. radio show

for children, the Quiz Kids, five days before the official presentation at an American Chemical Society meeting on November 11, 1945, when one of the listeners asked whether any new transuranium element beside plutonium and neptunium had been discovered during the war. The discovery of curium (242Cm and 240Cm), their production and compounds were later patented listing only Seaborg as the inventor.

The new element was named after Marie Skłodowska-Curie and her husband Pierre Curie who are noted for discovering radium and for their work in radioactivity. It followed the example of gadolinium, a lanthanide element above curium in the periodic table, which was named after the explorer of the rare earth elements Johan Gadolin:

- As the name for the element of atomic number 96 we should like to propose "curium", with symbol Cm. The evidence indicates that element 96 contains seven 5f electrons and is thus analogous to the element gadolinium with its seven 4f electrons in the regular rare earth series. On this base element 96 is named after the Curies in a manner analogous to the naming of gadolinium, in which the chemist Gadolin was honored.

The first curium samples were barely visible, and were identified by their radioactivity. Louis Werner and Isadore Perlman created the first substantial sample of 30 µg curium-242 hydroxide at the University of California in 1947 by bombarding americium-241 with neutrons. Macroscopic amounts of curium(III) fluoride

were obtained in 1950 by W. W. T. Crane, J. C. Wallmann and B. B.

Cunningham. Its magnetic susceptibility was very close to that of GdF3 providing the first experimental evidence for the +3 valence of curium in its compounds. Curium metal was produced only in 1951 by reduction of CmF3 with barium.

Characteristics

Physical

Double-hexagonal close packing with the layer sequence ABAC in the crystal structure of α-curium (A: green, B: blue, C: red)

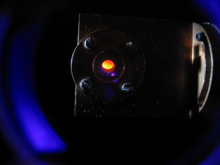

Orange fluorescence of Cm3+ ions in a solution of tris(hydrotris)pyrazolylborato-Cm(III) complex, excited at 396.6 nm.

A synthetic, radioactive element, curium is a hard, dense metal with a

silvery-white appearance and physical and chemical properties

resembling those of gadolinium.

Its melting point of 1340 °C is significantly higher than that of the

previous transuranic elements neptunium (637 °C), plutonium (639 °C) and

americium (1173 °C). In comparison, gadolinium melts at 1312 °C. The

boiling point of curium is 3110 °C. With a density of 13.52 g/cm3, curium is significantly lighter than neptunium (20.45 g/cm3) and plutonium (19.8 g/cm3),

but is heavier than most other metals. Between two crystalline forms of

curium, the α-Cm is more stable at ambient conditions. It has a

hexagonal symmetry, space group P63/mmc, lattice parameters a = 365 pm and c = 1182 pm, and four formula units per unit cell. The crystal consists of a double-hexagonal close packing with the layer sequence ABAC and so is isotypic with α-lanthanum. At pressures above 23 GPa, at room temperature, α-Cm transforms into β-Cm, which has a face-centered cubic symmetry, space group Fm3m and the lattice constant a = 493 pm. Upon further compression to 43 GPa, curium transforms to an orthorhombic

γ-Cm structure similar to that of α-uranium, with no further

transitions observed up to 52 GPa. These three curium phases are also

referred to as Cm I, II and III.

Curium has peculiar magnetic properties. Whereas its neighbor element americium shows no deviation from Curie-Weiss paramagnetism in the entire temperature range, α-Cm transforms to an antiferromagnetic state upon cooling to 65–52 K, and β-Cm exhibits a ferrimagnetic transition at about 205 K. Meanwhile, curium pnictides show ferromagnetic transitions upon cooling: 244CmN and 244CmAs at 109 K, 248CmP at 73 K and 248CmSb

at 162 K. The lanthanide analogue of curium, gadolinium, as well as its

pnictides, also show magnetic transitions upon cooling, but the

transition character is somewhat different: Gd and GdN become

ferromagnetic, and GdP, GdAs and GdSb show antiferromagnetic ordering.

In accordance with magnetic data, electrical resistivity of

curium increases with temperature – about twice between 4 and 60 K – and

then remains nearly constant up to room temperature. There is a

significant increase in resistivity over time (about 10 µΩ·cm/h) due to

self-damage of the crystal lattice by alpha radiation. This makes

uncertain the absolute resistivity value for curium (about 125 µΩ·cm).

The resistivity of curium is similar to that of gadolinium and of the

actinides plutonium and neptunium, but is significantly higher than that

of americium, uranium, polonium and thorium.

Under ultraviolet illumination, curium(III) ions exhibit strong and stable yellow-orange fluorescence with a maximum in the range about 590–640 nm depending on their environment. The fluorescence originates from the transitions from the first excited state 6D7/2 and the ground state 8S7/2. Analysis of this fluorescence allows monitoring interactions between Cm(III) ions in organic and inorganic complexes.

Chemical

Curium ions in solution almost exclusively assume the oxidation state of +3, which is the most stable oxidation state for curium. The +4 oxidation state is observed mainly in a few solid phases, such as CmO2 and CmF4. Aqueous curium(IV) is only known in the presence of strong oxidizers such as potassium persulfate, and is easily reduced to curium(III) by radiolysis and even by water itself.

The chemical behavior of curium is different from the actinides thorium

and uranium, and is similar to that of americium and many lanthanides. In aqueous solution, the Cm3+ ion is colorless to pale green, and Cm4+ ion is pale yellow. The optical absorption of Cm3+

ions contains three sharp peaks at 375.4, 381.2 and 396.5 nanometers

and their strength can be directly converted into the concentration of

the ions. The +6 oxidation state has only been reported once in solution in 1978, as the curyl ion (CmO2+

2): this was prepared from the beta decay of americium-242 in the americium(V) ion 242AmO+

2. Failure to obtain Cm(VI) from oxidation of Cm(III) and Cm(IV) may be due to the high Cm4+/Cm3+ ionization potential and the instability of Cm(V).

2): this was prepared from the beta decay of americium-242 in the americium(V) ion 242AmO+

2. Failure to obtain Cm(VI) from oxidation of Cm(III) and Cm(IV) may be due to the high Cm4+/Cm3+ ionization potential and the instability of Cm(V).

Curium ions are hard Lewis acids and thus form most stable complexes with hard bases. The bonding is mostly ionic, with a small covalent component. Curium in its complexes commonly exhibits a 9-fold coordination environment, within a tricapped trigonal prismatic geometry.

Isotopes

| Thermal neutron cross sections (barns) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 242Cm | 243Cm | 244Cm | 245Cm | 246Cm | 247Cm | |

| Fission | 5 | 617 | 1.04 | 2145 | 0.14 | 81.90 |

| Capture | 16 | 130 | 15.20 | 369 | 1.22 | 57 |

| C/F ratio | 3.20 | 0.21 | 14.62 | 0.17 | 8.71 | 0.70 |

| LEU spent fuel 20 years after 53 MWd/kg burnup | ||||||

| 3 common isotopes | 51 | 3700 | 390 |

| ||

| Fast reactor MOX fuel (avg 5 samples, burnup 66-120GWd/t) | ||||||

| Total curium 3.09×10−3% | 27.64% | 70.16% | 2.166% | 0.0376% | 0.000928% | |

| Isotope | 242Cm | 243Cm | 244Cm | 245Cm | 246Cm | 247Cm | 248Cm | 250Cm |

| Critical mass, kg | 25 | 7.5 | 33 | 6.8 | 39 | 7 | 40.4 | 23.5 |

About 20 radioisotopes and 7 nuclear isomers between 233Cm and 252Cm are known for curium, and no stable isotopes. The longest half-lives have been reported for 247Cm (15.6 million years) and 248Cm (348,000 years). Other long-lived isotopes are 245Cm (half-life 8500 years), 250Cm (8,300 years) and 246Cm (4,760 years). Curium-250 is unusual in that it predominantly (about 86%) decays via spontaneous fission. The most commonly used curium isotopes are 242Cm and 244Cm with the half-lives of 162.8 days and 18.1 years, respectively.

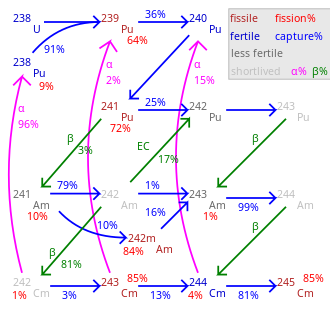

Transmutation flow between 238Pu and 244Cm in LWR. Fission percentage is 100 minus shown percentages. Total rate of transmutation varies greatly by nuclide. 245Cm–248Cm are long-lived with negligible decay.

All isotopes between 242Cm and 248Cm, as well as 250Cm, undergo a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction and thus in principle can act as a nuclear fuel in a reactor. As in most transuranic elements, the nuclear fission cross section is especially high for the odd-mass curium isotopes 243Cm, 245Cm and 247Cm. These can be used in thermal-neutron reactors, whereas a mixture of curium isotopes is only suitable for fast breeder reactors since the even-mass isotopes are not fissile in a thermal reactor and accumulate as burn-up increases. The mixed-oxide (MOX) fuel, which is to be used in power reactors, should contain little or no curium because the neutron activation of 248Cm will create californium. Californium is a strong neutron emitter, and would pollute the back end of the fuel cycle and increase the dose to reactor personnel. Hence, if the minor actinides

are to be used as fuel in a thermal neutron reactor, the curium should

be excluded from the fuel or placed in special fuel rods where it is the

only actinide present.

The adjacent table lists the critical masses

for curium isotopes for a sphere, without a moderator and reflector.

With a metal reflector (30 cm of steel), the critical masses of the odd

isotopes are about 3–4 kg. When using water (thickness ~20–30 cm) as the

reflector, the critical mass can be as small as 59 gram for 245Cm, 155 gram for 243Cm and 1550 gram for 247Cm. There is a significant uncertainty in these critical mass values. Whereas it is usually on the order of 20%, the values for 242Cm and 246Cm were listed as large as 371 kg and 70.1 kg, respectively, by some research groups.

Currently, curium is not used as a nuclear fuel owing to its low availability and high price. 245Cm and 247Cm have a very small critical mass and therefore could be used in portable nuclear weapons,

but none have been reported thus far. Curium-243 is not suitable for

this purpose because of its short half-life and strong α emission which

would result in excessive heat. Curium-247 would be highly suitable, having a half-life 647 times that of plutonium-239.

Occurrence

Several isotopes of curium were detected in the fallout from the Ivy Mike nuclear test.

The longest-lived isotope of curium, 247Cm, has a half-life of 15.6 million years. Therefore, any primordial

curium, that is curium present on the Earth during its formation,

should have decayed by now, although some of it would be detectable as

an extinct radionuclide as an excess of its nearly stable daughter 235U. Curium is produced artificially, in small quantities for research purposes. Furthermore, it occurs in spent nuclear fuel. Curium is present in nature in certain areas used for the atmospheric nuclear weapons tests, which were conducted between 1945 and 1980. So the analysis of the debris at the testing site of the first U.S. hydrogen bomb, Ivy Mike, (1 November 1952, Enewetak Atoll), beside einsteinium, fermium, plutonium and americium also revealed isotopes of berkelium, californium and curium, in particular 245Cm, 246Cm and smaller quantities of 247Cm, 248Cm and 249Cm. For reasons of military secrecy, this result was published only in 1956.

Atmospheric curium compounds are poorly soluble in common

solvents and mostly adhere to soil particles. Soil analysis revealed

about 4,000 times higher concentration of curium at the sandy soil

particles than in water present in the soil pores. An even higher ratio

of about 18,000 was measured in loam soils.

The transuranic elements from americium to fermium, including curium, occurred naturally in the natural nuclear fission reactor at Oklo, but no longer do so.

Synthesis

Isotope preparation

Curium is produced in small quantities in nuclear reactors, and by now only kilograms of it have been accumulated for the 242Cm and 244Cm and grams or even milligrams for heavier isotopes. This explains the high price of curium, which has been quoted at 160–185 USD per milligram, with a more recent estimate at US$2,000/g for 242Cm and US$170/g for 244Cm. In nuclear reactors, curium is formed from 238U in a series of nuclear reactions. In the first chain, 238U captures a neutron and converts into 239U, which via β− decay transforms into 239Np and 239Pu.

-

(1)

Further neutron capture followed by β−-decay produces the 241Am isotope of americium which further converts into 242Cm:

-

.(2)

For research purposes, curium is obtained by irradiating not uranium

but plutonium, which is available in large amounts from spent nuclear

fuel. A much higher neutron flux is used for the irradiation that

results in a different reaction chain and formation of 244Cm:

-

(3)

Curium-244 decays into 240Pu by emission of alpha

particle, but it also absorbs neutrons resulting in a small amount of

heavier curium isotopes. Among those, 247Cm and 248Cm are popular in scientific research because of their long half-lives. However, the production rate of 247Cm in thermal neutron reactors is relatively low because of it is prone to undergo fission induced by thermal neutrons. Synthesis of 250Cm via neutron absorption is also rather unlikely because of the short half-life of the intermediate product 249Cm (64 min), which converts by β− decay to the berkelium isotope 249Bk.

-

(4)

The above cascade of (\ce n,γ) reactions produces a mixture of

different curium isotopes. Their post-synthesis separation is

cumbersome, and therefore a selective synthesis is desired. Curium-248

is favored for research purposes because of its long half-life. The most

efficient preparation method of this isotope is via α-decay of the californium isotope 252Cf, which is available in relatively large quantities due to its long half-life (2.65 years). About 35–50 mg of 248Cm is being produced by this method every year. The associated reaction produces 248Cm with isotopic purity of 97%.

-

(5)

Another interesting for research isotope 245Cm can be obtained from the α-decay of 249Cf, and the latter isotope is produced in minute quantities from the β−-decay of the berkelium isotope 249Bk.

-

(6)

Metal preparation

Chromatographic elution curves revealing the similarity between Tb, Gd, Eu lanthanides and corresponding Bk, Cm, Am actinides.

Most synthesis routines yield a mixture of different actinide isotopes as oxides,

from which a certain isotope of curium needs to be separated. An

example procedure could be to dissolve spent reactor fuel (e.g. MOX fuel) in nitric acid, and remove the bulk of the uranium and plutonium using a PUREX (Plutonium – URanium EXtraction) type extraction with tributyl phosphate in a hydrocarbon. The lanthanides and the remaining actinides are then separated from the aqueous residue (raffinate)

by a diamide-based extraction to give, after stripping, a mixture of

trivalent actinides and lanthanides. A curium compound is then

selectively extracted using multi-step chromatographic and centrifugation techniques with an appropriate reagent. Bis-triazinyl bipyridine complex has been recently proposed as such reagent which is highly selective to curium. Separation of curium from a very similar americium can also be achieved by treating a slurry of their hydroxides in aqueous sodium bicarbonate with ozone

at elevated temperature. Both americium and curium are present in

solutions mostly in the +3 valence state; whereas americium oxidizes to

soluble Am(IV) complexes, curium remains unchanged and can thus be

isolated by repeated centrifugation.

Metallic curium is obtained by reduction

of its compounds. Initially, curium(III) fluoride was used for this

purpose. The reaction was conducted in the environment free from water

and oxygen, in the apparatus made of tantalum and tungsten, using elemental barium or lithium as reducing agents.

Another possibility is the reduction of curium(IV) oxide using a magnesium-zinc alloy in a melt of magnesium chloride and magnesium fluoride.

Compounds and reactions

Oxides

Curium readily reacts with oxygen forming mostly Cm2O3 and CmO2 oxides, but the divalent oxide CmO is also known. Black CmO2 can be obtained by burning curium oxalate (Cm2(C2O4)3), nitrate (Cm(NO3)3) or hydroxide in pure oxygen. Upon heating to 600–650 °C in vacuum (about 0.01 Pa), it transforms into the whitish Cm2O3:

- .

Alternatively, Cm2O3 can be obtained by reducing CmO2 with molecular hydrogen:

Furthermore, a number of ternary oxides of the type M(II)CmO3 are known, where M stands for a divalent metal, such as barium.

Thermal oxidation of trace quantities of curium hydride (CmH2–3) has been reported to produce a volatile form of CmO2 and the volatile trioxide CmO3, one of the two known examples of the very rare +6 state for curium.

Another observed species was reported to behave similarly to a supposed

plutonium tetroxide and was tentatively characterized as CmO4, with curium in the extremely rare +8 state; however, new experiments seem to indicate that CmO4 does not exist, and have cast doubt on the existence of PuO4 as well.

Halides

The colorless curium(III) fluoride (CmF3)

can be produced by introducing fluoride ions into

curium(III)-containing solutions. The brown tetravalent curium(IV)

fluoride (CmF4) on the other hand is only obtained by reacting curium(III) fluoride with molecular fluorine:

A series of ternary fluorides are known of the form A7Cm6F31, where A stands for alkali metal.

The colorless curium(III) chloride (CmCl3) is produced in the reaction of curium(III) hydroxide (Cm(OH)3) with anhydrous hydrogen chloride

gas. It can further be converted into other halides, such as

curium(III) bromide (colorless to light green) and curium(III) iodide

(colorless), by reacting it with the ammonia salt of the corresponding halide at elevated temperature of about 400–450 °C:

An alternative procedure is heating curium oxide to about 600 °C with the corresponding acid (such as hydrobromic for curium bromide). Vapor phase hydrolysis of curium(III) chloride results in curium oxychloride:

Chalcogenides and pnictides

Sulfides, selenides and tellurides of curium have been obtained by treating curium with gaseous sulfur, selenium or tellurium in vacuum at elevated temperature.The pnictides of curium of the type CmX are known for the elements nitrogen, phosphorus, arsenic and antimony. They can be prepared by reacting either curium(III) hydride (CmH3) or metallic curium with these elements at elevated temperatures.

Organocurium compounds and biological aspects

Predicted curocene structure

Organometallic complexes analogous to uranocene are known also for other actinides, such as thorium, protactinium, neptunium, plutonium and americium. Molecular orbital theory predicts a stable "curocene" complex (η8-C8H8)2Cm, but it has not been reported experimentally yet.

Formation of the complexes of the type Cm(n-C3H7-BTP)3, where BTP stands for 2,6-di(1,2,4-triazin-3-yl)pyridine, in solutions containing n-C3H7-BTP and Cm3+ ions has been confirmed by EXAFS.

Some of these BTP-type complexes selectively interact with curium and

therefore are useful in its selective separation from lanthanides and

another actinides. Dissolved Cm3+ ions bind with many organic compounds, such as hydroxamic acid, urea, fluorescein and adenosine triphosphate. Many of these compounds are related to biological activity of various microorganisms.

The resulting complexes exhibit strong yellow-orange emission under UV

light excitation, which is convenient not only for their detection, but

also for studying the interactions between the Cm3+ ion and the ligands via changes in the half-life (of the order ~0.1 ms) and spectrum of the fluorescence.

Curium has no biological significance. There are a few reports on biosorption of Cm3+ by bacteria and archaea, however no evidence for incorporation of curium into them.

Applications

Radionuclides

The radiation from curium is so strong that the metal glows purple in the dark.

Curium is one of the most radioactive isolable elements. Its two most common isotopes 242Cm and 244Cm

are strong alpha emitters (energy 6 MeV); they have relatively short

half-lives of 162.8 days and 18.1 years, and produce as much as 120 W/g

and 3 W/g of thermal energy, respectively. Therefore, curium can be used in its common oxide form in radioisotope thermoelectric generators like those in spacecraft. This application has been studied for the 244Cm isotope, while 242Cm was abandoned due to its prohibitive price of around 2000 USD/g. 243Cm

with a ~30 year half-life and good energy yield of ~1.6 W/g could make a

suitable fuel, but it produces significant amounts of harmful gamma and beta radiation from radioactive decay products. Though as an α-emitter, 244Cm

requires a much thinner radiation protection shielding, it has a high

spontaneous fission rate, and thus the neutron and gamma radiation rate

are relatively strong. As compared to a competing thermoelectric

generator isotope such as 238Pu, 244Cm emits a

500-fold greater fluence of neutrons, and its higher gamma emission

requires a shield that is 20 times thicker — about 2 inches of lead for a

1 kW source, as compared to 0.1 in for 238Pu. Therefore, this application of curium is currently considered impractical.

A more promising application of 242Cm is to produce 238Pu, a more suitable radioisotope for thermoelectric generators such as in cardiac pacemakers. The alternative routes to 238Pu use the (n,γ) reaction of 237Np, or the deuteron bombardment of uranium, which both always produce 236Pu as an undesired by-product — since the latter decays to 232U with strong gamma emission. Curium is also a common starting material for the production of higher transuranic elements and transactinides. Thus, bombardment of 248Cm with neon (22Ne), magnesium (26Mg), or calcium (48Ca) yielded certain isotopes of seaborgium (265Sg), hassium (269Hs and 270Hs), and livermorium (292Lv, 293Lv, and possibly 294Lv). Californium was discovered when a microgram-sized target of curium-242 was irradiated with 35 MeV alpha particles using the 60-inch (150 cm) cyclotron at Berkeley:

- 242

96Cm

+ 4

2He

→ 245

98Cf

+ 1

0n

Only about 5,000 atoms of californium were produced in this experiment.

Alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer of a Mars exploration rover

X-ray spectrometer

The most practical application of 244Cm — though rather limited in total volume — is as α-particle source in the alpha particle X-ray spectrometers (APXS). These instruments were installed on the Sojourner, Mars, Mars 96, Mars Exploration Rovers and Philae comet lander, as well as the Mars Science Laboratory to analyze the composition and structure of the rocks on the surface of planet Mars. APXS was also used in the Surveyor 5–7 moon probes but with a 242Cm source.

An elaborated APXS setup is equipped with a sensor head

containing six curium sources having the total radioactive decay rate of

several tens of millicuries (roughly a gigabecquerel).

The sources are collimated on the sample, and the energy spectra of the

alpha particles and protons scattered from the sample are analyzed (the

proton analysis is implemented only in some spectrometers). These

spectra contain quantitative information on all major elements in the

samples except for hydrogen, helium and lithium.

Safety

Owing to

its high radioactivity, curium and its compounds must be handled in

appropriate laboratories under special arrangements. Whereas curium

itself mostly emits α-particles which are absorbed by thin layers of

common materials, some of its decay products emit significant fractions

of beta and gamma radiation, which require a more elaborate protection. If consumed, curium is excreted within a few days and only 0.05% is absorbed in the blood. From there, about 45% goes to the liver, 45% to the bones, and the remaining 10% is excreted. In the bone, curium accumulates on the inside of the interfaces to the bone marrow and does not significantly redistribute with time; its radiation destroys bone marrow and thus stops red blood cell creation. The biological half-life of curium is about 20 years in the liver and 50 years in the bones. Curium is absorbed in the body much more strongly via inhalation, and the allowed total dose of 244Cm in soluble form is 0.3 μC. Intravenous injection of 242Cm and 244Cm containing solutions to rats increased the incidence of bone tumor, and inhalation promoted pulmonary and liver cancer.

Curium isotopes are inevitably present in spent nuclear fuel with a concentration of about 20 g/tonne. Among them, the 245Cm–248Cm isotopes have decay times of thousands of years and need to be removed to neutralize the fuel for disposal.

The associated procedure involves several steps, where curium is first

separated and then converted by neutron bombardment in special reactors

to short-lived nuclides. This procedure, nuclear transmutation, while well documented for other elements, is still being developed for curium.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}{}\\{\ce {^{252}_{98}Cf ->[\alpha][2.645\ {\ce {yr}}] ^{248}_{96}Cm}}\\{}\end{matrix}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c6cc4394eb604706a66a7112cda30cf38f857380)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {^{249}_{97}Bk ->[\beta^-][330\ {\ce {d}}] ^{249}_{98}Cf ->[\alpha][351\ {\ce {yr}}] ^{245}_{96}Cm}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7ccddd548852fda4a6af794bec61eda1293ebdd8)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {4CmO2 ->[\Delta T] 2Cm2O3 + O2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d347ad5669ad313e0453be3c15f15e400c2d5ef8)