Historical segregation

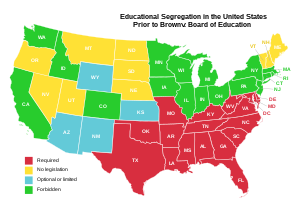

Jim Crow laws formalized school segregation in the United States, 1877-1954.

The formal segregation of blacks and whites in the United States began long before the passage of Jim Crow laws following the end of the Reconstruction Era in 1877. The United States Supreme Court's Dred Scott

decision upheld the denial of citizenship to African Americans and

found that descendants of slaves are "so far inferior that they had no

rights which the white man was bound to respect."

Following the American Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation,

the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteeing "equal protection under the

law" was ratified in 1868 and citizenship was extended to African

Americans. Congress also passed the Civil Rights Act of 1875 banning

racial discrimination in public accommodations. But the Supreme Court

struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875 in 1883 finding that

discrimination by individuals or private businesses is constitutional.

The Reconstruction Era

saw efforts at integration in the South, but Jim Crow laws followed and

were also passed by state legislatures in the Southwest and Midwest,

segregating blacks and whites in all aspects of public life, including

attendance of public schools.

While African Americans faced legal segregation in civil society,

Mexican Americans who lived in southwestern states often dealt with de facto segregation even where no laws explicitly barred their access to schools or other public facilities.

The proponents of Mexican-American segregation were often officials who

worked at the state and local school level and often defended the

creation and sustaining of separate "Mexican schools". In other cases, the NAACP

challenged segregation policies in institutions where exclusion was

targeted only at African-American students and where there was an

already established Mexican-American presence.

The constitutionality of Jim Crow laws was upheld in the Supreme Court's decision in Plessy v. Ferguson

(1896), which ruled that separate facilities for blacks and whites were

permissible provided that the facilities were of equal quality.

The fact that separate facilities for blacks and other minorities were

chronically underfunded and of lesser quality was not successfully

challenged in court for decades. This decision was subsequently

overturned in 1954, when the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education ended de jure segregation in the United States. In the decade following Brown, the South resisted enforcement of the Court's decision.

States and school districts did little to reduce segregation, and

schools remained almost completely segregated until 1968, after

Congressional passage of civil rights legislation.

Desegregation efforts reached their peak in the late 1960s and early

1970s, a period in which the South transitioned from complete

segregation to being the nation's most integrated region.

Parents of both African-American and Mexican-American students

challenged school segregation in coordination with civil rights

organizations such as the NAACP, ACLU, and LULAC.

Both groups challenged discriminatory policies through litigation in

courts, with varying success, at times challenging policies. They often

had small successes.

For instance, the NAACP initially challenged graduate and professional

school segregation because they believed that desegregation at this

level would result in the least backlash and opposition by whites.

Various means to desegregate schools have been tried including busing students.

Catholic Schools

Catholic

schools in the South generally followed the pattern of segregation of

public schools, sometimes forced to do so by law. Most Catholic

dioceses began moving ahead of public schools to desegregate. In St.

Louis, Catholic schools were desegregated in 1947. In Washington, DC, the Catholic schools were desegregated in 1948. Catholic schools in Tennessee were desegregated in 1954, Atlanta in 1962, Mississippi in 1965, all ahead of the public school systems.

More recent segregation

From 1968-1980, segregation between blacks and whites in schools declined.

School integration peaked in the 1980s and then gradually declined over

the course of the 1990s, as income differences increased.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, minority students attended schools with a

declining proportion of white students, so that the rate of segregation

as measured as isolation resembled that of the 1960s.

There is some disagreement about what to make of trends since the

1980s; while some researchers have presented trends as evidence of

"resegregation," others argue that changing demographics in school

districts, including class and income, are responsible for most of the

changes in the racial composition of schools.

A 2013 study by Jeremy Fiel found that, "for the most part,

compositional changes are to blame for the declining presence of whites

in minorities' schools," and that racial balance increased from 1993 to

2010.

The study found that minority students became more isolated and less

exposed to whites, but that all students became more evenly distributed

across schools. Another 2013 study found that segregation measured as

exposure increased over the previous 25 years due to changing

demographics.

The study did not, however, find an increase in racial balance; rather,

racial unevenness remained stable over that time period. Researcher

Kori Stroub found that the "racial/ethnic resegregation of public

schools observed over the 1990s has given way to a period of modest

reintegration," but that segregation between school districts has

increased even though within-district segregation is low. Fiel believes that increasing interdistrict segregation will exacerbate racial isolation.

Sources of contemporary segregation

Residential segregation

A principal source of school segregation is the persistence of residential segregation

in American society; residence and school assignment are closely linked

due to the widespread tradition of locally controlled schools. Residential segregation is related to growing income inequality in the United States.

A study conducted by Sean Reardon

and John Yun found that from 1990-2000, residential black/white and

Hispanic/white segregation declined by a modest amount in the United

States, while public school segregation increased slightly during the

same time period. Because the two variables moved in opposite

directions, changes in residential patterns are not responsible for

changes in school segregation trends. Rather, the study determined that

in 1990, schools showed less segregation than neighborhoods, indicating

that local policies were helping to ameliorate the effects of

residential segregation on school composition. By 2000, however, racial

composition of schools had become more closely correlated to

neighborhood composition, indicating that public policies no longer

redistributed students as evenly as before.

A 2013 study corroborated these findings, showing that the

relationship between residential and school segregation became stronger

over the decade 2000-2010. In 2000, segregation of blacks in schools was

lower than in their neighborhoods; by 2010, the two patterns of

segregation were "nearly identical."

Supreme Court rulings

Although the US Supreme Court's in Brown v. Board of Education

set desegregation efforts in motion, subsequent rulings have created

serious obstacles to continued integration. The court's 1970 ruling in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education furthered desegregation efforts by upholding busing

as a constitutional means to achieve integration within a school

district, but the ruling had no effect on the increasing level of

segregation between school districts. The court's ruling in Milliken v. Bradley in 1974 prohibited interdistrict desegregation by busing.

The 1990 decision in Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell

declared that once schools districts had made a practicable, "good

faith" effort to desegregate, they could be declared to have achieved

"unitary" status, releasing them from court oversight. The decision allowed schools to end previous desegregation efforts even in cases where a return to segregation was likely. The court's ruling in Freeman v. Pitts

went further, ruling that districts could be released from oversight in

"incremental stages," meaning that courts would continue to supervise

only those aspects of integration that had not yet been achieved.

A 2012 study determined that "half of all districts ever under

court-ordered desegregation [had] been released from court oversight,

with most of the releases occurring in the last 20 years." The study

found that segregation levels in school districts did not rise sharply

following court dismissal, but rather increased gradually for the next

10 to 12 years. As compared to districts that had never been placed

under court supervision, districts that had achieved unitary status and

were released from court-ordered desegregation had a subsequent change

in segregation patterns that was 10 times as great. The study concludes

that "court-ordered desegregation plans are effective in reducing racial

school segregation, but…their effects fade over time in the absence of

continued court oversight."

In a pair of rulings in 2007 (Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 and Meredith v. Jefferson County Board of Education),

the court's decision limited schools' ability to use race as a

consideration in school assignment plans. In both cases, the Court

struck down school assignment plans designed to ensure that the racial

composition of schools roughly reflected the composition of the district

as a whole, saying that the plans were not "narrowly tailored" to

achieve the stated goal and that race-neutral alternatives had not been

given adequate consideration.

School choice

While greater school choice

could potentially increase integration by drawing students from larger

and more geographically diverse areas (as opposed to segregated

neighborhoods), expanded choice often has the opposite effect.

Studies conducted on the relationship between expanded school choice

and school segregation show that when studies compare the racial/ethnic

composition of charter schools

to local public schools, researchers generally find that charter

schools preserve or intensify existing racial and economic segregation,

and/or facilitate white flight from public schools.

Furthermore, studies that compare individual students' demographic

characteristics to the schools they are leaving (public schools) and the

schools they are switching to (charter schools) generally demonstrate

that students "leave more diverse public schools and enroll in less

diverse charter schools."

Private schools constitute a second important type of school

choice. A 2002 study found that private schools continued to contribute

to the persistence of school segregation in the South over the course of

the 1990s. Enrollment of whites in private schools increased sharply in

the 1970s, remained unchanged in the 1980s, and increased again over

the course of the 1990s. Because the changes over the latter two decades

was not substantial, however, researcher Sean Reardon

concludes that changes in private school enrollment is not a likely

contributor to any changes in schools segregation patterns during that

time.

In contrast to charter and private schools, magnet schools generally foster racial integration rather than hinder it.

Such schools were initially presented as an alternative to unpopular

busing policies, and included explicit desegregation goals along with

provisions for recruiting and providing transportation for diverse

populations.

Although today's magnet schools are no longer as explicitly oriented

towards integration efforts, they continue to be less racially isolated

than other forms of school choice.

Implications of segregation

Educational outcomes

The

level of racial segregation in schools has important implications for

the educational outcomes of minority students. Desegregation efforts of

the 1970s and 1980s led to substantial academic gains for black

students; as integration increased, blacks' educational attainment increased while that of whites remained largely unchanged.

Historically, greater access to schools with higher enrollments of

white students helped "reduce blacks' high school dropout rate, reduce

the black-white test score gap, and improve outcomes for black in areas such as earnings, health, and incarceration."

Nationwide, minority students continue to be concentrated in

high-poverty, low-achieving schools, while white students are more

likely to attend high-achieving, more affluent schools. Resources such as funds and high-quality teachers attach unequally to schools according to racial and socioeconomic composition.

Schools with high proportions of minority enrollment are often

characterized by "less experienced and less qualified teachers, high

levels of teacher turnover, less successful peer groups and inadequate

facilities and learning materials." These schools also tend to have less challenging curricula and fewer offerings of Advanced Placement courses.

Access to resources is not the only factor determining education

outcomes; the very racial composition of schools can have an effect

independent of the level of other resources. A 2009 study determined

that attending school with a high proportion of black students

negatively affected black academic achievement, even after controlling

for school quality, differences in ability, and family background. The

effect of racial composition on white achievement was insignificant.

Short-term versus long-term outcomes

The

research that has been conducted on the effects of school segregation

can be divided into studies that observe short-term and long-term

outcomes of segregated schooling; these outcomes can be either academic

or non-academic in nature. Studies of short-term outcomes observe the

relationship between school segregation and outcomes such as academic

achievement (test scores), racial prejudice/fear, and cross-cultural

friendships. Long-term outcomes may refer to educational attainment,

occupational attainment, adults' intergroup relations, crime and

violence, and civic engagement.

The mixed findings of research on the effects of integration on

black students has resulted in ambiguous conclusions as to the influence

of desegregation plans.

Generally, integration has a small but beneficial impact on short-term

outcomes for blacks (i.e. education achievement), and a clearly

beneficial impact on longer-term outcomes, such as school attainment

(i.e. level of education attained) and earnings.

Integrated education is positively related to short-term outcomes such

as K–12 school performance, cross-racial friendships, acceptance of

cultural differences, and declines in racial fears and prejudice. In the

long run, integration is associated with higher educational and

occupational attainment across all ethnic groups, better intergroup

relations, greater likelihood of living and working in an integrated

environment, lower likelihood of involvement with the criminal justice

system, espousal of democratic values, and greater civic engagement.

A 1994 study found support for the theory that interracial

contact in elementary or secondary school positively affects long-term

outcomes in a way that can help blacks overcome perpetual segregation.

The study reviewed previous research and determined that, as compared

to segregated blacks, desegregated blacks are more likely to set higher

occupational aspirations, attend desegregated colleges, have

desegregated social and professional networks as adults, gain

desegregated employment, and work in white-collar and professional jobs

in the private sector.

Short-term and long-term benefits of integration are found for

minority and majority students alike. Students who attend integrated

schools are more likely to live in diverse neighborhoods as adults than

those students who attended more segregated schools. Integrated schools

also reduce the maintenance of stereotypes and prevent the formation of

prejudices in both majority and minority students.

Proposed policies

Although the Supreme Court's ruling in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1

limited school districts' ability to take race into account during the

school assignment process, the ruling did not prohibit racial

considerations altogether. According to the UCLA Civil Rights Project, a

school district may consider race when using any of the following

strategies: "site selection of new schools; drawing attendance zones

with general recognition of the racial demographics of neighborhoods;

allocating resources for special programs; recruiting students and

faculty in a targeted manner; [and] tracking enrollments, performance,

and other statistics by race."

Districts may use income-based school assignment policies to try to

indirectly achieve racial integration, but in practice such policies are

not guaranteed to produce even a modest degree of racial integration.

Other researchers argue that, given restrictive court rulings and

the increasingly strong relationship between neighborhood and school

segregation, integration efforts should instead focus on reducing racial

segregation in neighborhoods. This could be achieved, in part, by greater enforcement of the Fair Housing Act and/or removal of low-density zoning laws.

Policy could also set aside low-income housing in new community

developments that have a strong school district based on income.

In the school choice realm, policy can ensure that greater choice

facilitates integration by, for instance, adopting "civil rights

policies" for charter schools.

Such policies could require charter schools to recruit diverse faculty

and students, provide transportation to ensure access for poor students,

and/or have a racial composition that does not differ greatly from that

of the public school population.

Expanding the availability of magnet schools—which were initially

created with school desegregation efforts and civil rights policies in

mind—could also lead to increased integration, especially in those

instances when magnet schools can draw students from separate (and

segregated) attendance zones and school districts.

Alternatively, states could move towards county- or region-level school

districting, allowing students to be drawn from larger and more diverse

geographic areas.

According to some scholars, school assignment policies should

primarily focus on socioeconomic integration rather than racial

integration. As Richard D. Kahlenberg writes, "Racial integration is a

very important aim, but if one's goal is boosting academic achievement,

what really matters is economic integration."

Kahlenberg refers to a body of research showing that the low overall

socioeconomic status of a school is clearly linked to less learning for

students, even after controlling for age, race, and family socioeconomic

status. In particular, the socioeconomic composition of a school may

lead to lower student achievement through its effect on "school

processes," such as academic climate and teachers' expectations of

students' ability to learn.

If reforms could equalize these school processes across schools,

socioeconomic and racial integration policies might not be necessary to

close achievement gaps.

Sociologist Amy Stuart Wells, however, argues that the original intent

of school desegregation was to improve blacks' access to important

social institutions and opportunities, thereby improving their long-run

life outcomes.

Discussions about ending racial integration policies, though, largely

focus on the relationship between integration and short-run outcomes

such as test scores. In Stuart's view, long-term outcomes should be emphasized in order to appreciate the true social importance of integration.