Modern Western social movements became possible through education (the wider dissemination of literature) and increased mobility of labor due to the industrialization and urbanization of 19th-century societies. It is sometimes argued that the freedom of expression, education and relative economic independence prevalent in the modern Western culture

are responsible for the unprecedented number and scope of various

contemporary social movements. However, others point out that many of

the social movements of the last hundred years grew up, like the Mau Mau in Kenya, to oppose Western colonialism. Either way, social movements have been and continued to be closely connected with democratic political systems. Occasionally, social movements have been involved in democratizing

nations, but more often they have flourished after democratization.

Over the past 200 years, they have become part of a popular and global

expression of dissent.

Modern movements often utilize technology and the internet to mobilize people globally. Adapting to communication trends is a common theme among successful movements. Research is beginning to explore how advocacy organizations linked to social movements in the U.S. and Canada use social media to facilitate civic engagement and collective action. The systematic literature review of Buettner & Buettner analyzed the role of Twitter during a wide range of social movements (2007 WikiLeaks, 2009 Moldova, 2009 Austria student protest, 2009 Israel-Gaza, 2009 Iran green revolution, 2009 Toronto G20, 2010 Venezuela, 2010 Germany Stuttgart21, 2011 Egypt, 2011 England, 2011 US Occupy movement, 2011 Spain Indignados, 2011 Greece Aganaktismenoi movements, 2011 Italy, 2011 Wisconsin labor protests, 2012 Israel Hamas, 2013 Brazil Vinegar, 2013 Turkey).

Political science and sociology have developed a variety of theories and empirical research on social movements. For example, some research in political science highlights the relation between popular movements and the formation of new political parties as well as discussing the function of social movements in relation to agenda setting and influence on politics.

Modern movements often utilize technology and the internet to mobilize people globally. Adapting to communication trends is a common theme among successful movements. Research is beginning to explore how advocacy organizations linked to social movements in the U.S. and Canada use social media to facilitate civic engagement and collective action. The systematic literature review of Buettner & Buettner analyzed the role of Twitter during a wide range of social movements (2007 WikiLeaks, 2009 Moldova, 2009 Austria student protest, 2009 Israel-Gaza, 2009 Iran green revolution, 2009 Toronto G20, 2010 Venezuela, 2010 Germany Stuttgart21, 2011 Egypt, 2011 England, 2011 US Occupy movement, 2011 Spain Indignados, 2011 Greece Aganaktismenoi movements, 2011 Italy, 2011 Wisconsin labor protests, 2012 Israel Hamas, 2013 Brazil Vinegar, 2013 Turkey).

Political science and sociology have developed a variety of theories and empirical research on social movements. For example, some research in political science highlights the relation between popular movements and the formation of new political parties as well as discussing the function of social movements in relation to agenda setting and influence on politics.

Definitions

There is no single consensus definition of a social movement.

Mario Diani argues that nearly all definitions share three criteria: "a

network of informal interactions between a plurality of individuals,

groups and/or organizations, engaged in a political or cultural

conflict, on the basis of a shared collective identity."

Sociologist Charles Tilly

defines social movements as a series of contentious performances,

displays and campaigns by which ordinary people make collective claims

on others. For Tilly, social movements are a major vehicle for ordinary people's participation in public politics. He argues that there are three major elements to a social movement:

- Campaigns: a sustained, organized public effort making collective claims of target authorities;

- Repertoire (repertoire of contention): employment of combinations from among the following forms of political action: creation of special-purpose associations and coalitions, public meetings, solemn processions, vigils, rallies, demonstrations, petition drives, statements to and in public media, and pamphleteering; and

- WUNC displays: participants' concerted public representation of worthiness, unity, numbers, and commitments on the part of themselves and/or their constituencies.

Sidney Tarrow

defines a social movement as "collective challenges [to elites,

authorities, other groups or cultural codes] by people with common

purposes and solidarity in sustained interactions with elites, opponents

and authorities." He specifically distinguishes social movements from

political parties and advocacy groups.

The sociologists John McCarthy and Mayer Zald define as a social

movement as "a set of opinions and beliefs in a population which

represents preferences for changing some elements of the social

structure and/or reward distribution of a society."

According to Paul van Seeters and Paul James defining a social movement entails a few minimal conditions of ‘coming together’:

(1.) the formation of some kind of collective identity; (2.) the development of a shared normative orientation; (3.) the sharing of a concern for change of the status quo and (4.) the occurrence of moments of practical action that are at least subjectively connected together across time addressing this concern for change. Thus we define a social movement as a form of political association between persons who have at least a minimal sense of themselves as connected to others in common purpose and who come together across an extended period of time to effect social change in the name of that purpose.

History

Beginnings

Satirical engraving of Wilkes by William Hogarth. Wilkes is holding two editions of The North Briton.

The early growth of social movements was connected to broad economic

and political changes in England in the mid-18th century, including political representation, market capitalization, and proletarianization. The first mass social movement catalyzed around the controversial political figure, John Wilkes. As editor of the paper The North Briton, Wilkes vigorously attacked the new administration of Lord Bute and the peace terms that the new government accepted at the 1763 Treaty of Paris at the end of the Seven Years' War. Charged with seditious libel, Wilkes was arrested after the issue of a general warrant, a move that Wilkes denounced as unlawful - the Lord Chief Justice

eventually ruled in Wilkes favour. As a result of this episode, Wilkes

became a figurehead to the growing movement for popular sovereignty

among the middle classes - people began chanting, "Wilkes and Liberty"

in the streets.

After a later period of exile, brought about by further charges of libel and obscenity, Wilkes stood for the Parliamentary seat at Middlesex, where most of his support was located. When Wilkes was imprisoned in the King's Bench Prison

on 10 May 1768, a mass movement of support emerged, with large

demonstrations in the streets under the slogan "No liberty, no King." Stripped of the right to sit in Parliament, Wilkes became an Alderman of London in 1769, and an activist group called the Society for the Supporters of the Bill of Rights began aggressively promoting his policies.

This was the first ever sustained social movement; -it involved public

meetings, demonstrations, the distribution of pamphlets on an

unprecedented scale and the mass petition march. However, the movement

was careful not to cross the line into open rebellion; - it tried to

rectify the faults in governance through appeals to existing legal

precedents and was conceived of as an extra-Parliamentary form of

agitation to arrive at a consensual and constitutional arrangement.

The force and influence of this social movement on the streets of

London compelled the authorities to concede to the movement's demands.

Wilkes was returned to Parliament, general warrants were declared as unconstitutional and press freedom was extended to the coverage of Parliamentary debates.

The Gordon Riots, depicted in a painting by John Seymour Lucas

A much larger movement of anti-Catholic protest was triggered by the Papists Act 1778, which eliminated a number of the penalties and disabilities endured by Roman Catholics in England, and formed around Lord George Gordon, who became the President of the Protestant Association in 1779. The Association had the support of leading Calvinist religious figures, including Rowland Hill, Erasmus Middleton, and John Rippon. Gordon was an articulate propagandist and he inflamed the mob with fears of Papism and a return to absolute monarchical rule.

The situation deteriorated rapidly, and in 1780, after a meeting of the

Protestant Association, its members subsequently marched on the House of Commons to deliver a petition demanding the repeal of the Act, which the government refused to do. Soon, large riots broke out across London and embassies and Catholic owned businesses were attacked by angry mobs.

Other political movements that emerged in the late 18th century included the British abolitionist movement against slavery

(becoming one between the sugar boycott of 1791 and the second great

petition drive of 1806), and possibly the upheaval surrounding the French and American Revolutions.

In the opinion of Eugene Black (1963), "...association made possible

the extension of the politically effective public. Modern extra

parliamentary political organization is a product of the late eighteenth

century [and] the history of the age of reform cannot be written

without it.

Growth and spread

The Great Chartist Meeting on Kennington Common, London in 1848.

From 1815, Britain after victory in the Napoleonic Wars

entered a period of social upheaval characterised by the growing

maturity of the use of social movements and special-interest

associations. Chartism was the first mass movement of the growing working-class in the world. It campaigned for political reform between 1838 and 1848 with the People's Charter of 1838 as its manifesto – this called for universal suffrage and the implementation of the secret ballot, amongst other things. The term "social movements" was introduced in 1848 by the German Sociologist Lorenz von Stein in his book Socialist and Communist Movements since the Third French Revolution (1848) in which he introduced the term "social movement" into scholarly discussions - actually depicting in this way political movements fighting for the social rights understood as welfare rights.

Martin Luther King Jr. was a leader in the Civil Rights Movement, one of the most famous social movements of the 20th century.

The labor movement and socialist movement of the late 19th century are seen as the prototypical social movements, leading to the formation of communist and social democratic

parties and organisations. These tendencies were seen in poorer

countries as pressure for reform continued, for example in Russia with

the Russian Revolution of 1905 and of 1917, resulting in the collapse of the Czarist regime around the end of the First World War.

In 1945, Britain after victory in the Second World War entered a period of radical reform and change. In the post-war period, Feminism, gay rights movement, peace movement, Civil Rights Movement, anti-nuclear movement and environmental movement emerged, often dubbed the New Social Movements They led, among other things, to the formation of green parties and organisations influenced by the new left. Some find in the end of the 1990s the emergence of a new global social movement, the anti-globalization movement. Some social movement scholars posit that with the rapid pace of globalization, the potential for the emergence of new type of social movement is latent—they make the analogy to national movements of the past to describe what has been termed a global citizens movement.

Key processes

Several key processes lie behind the history of social movements. Urbanization led to larger settlements, where people of similar goals could find each other, gather and organize. This facilitated social interaction

between scores of people, and it was in urban areas that those early

social movements first appeared. Similarly, the process of

industrialization which gathered large masses of workers in the same

region explains why many of those early social movements addressed

matters such as economic wellbeing, important to the worker class. Many other social movements were created at universities, where the process of mass education brought many people together. With the development of communication

technologies, creation and activities of social movements became easier

– from printed pamphlets circulating in the 18th century coffeehouses to newspapers and Internet, all those tools became important factors in the growth of the social movements. Finally, the spread of democracy and political rights like the freedom of speech made the creation and functioning of social movements much easier.

Mass Mobilization

Nascent

social movements often fail to achieve their objectives because they

fail to mobilize sufficient numbers of people. Srdja Popovic, author of

Blueprint for Revolution, and spokesperson for OTPOR!,

says that movements succeed when they address issues that people

actually care about. “It’s unrealistic to expect people to care about

more than what they already care about, and any attempt to make them do

so is bound to fail.” Activists too often make the mistake of trying to

convince people to address their issues. A mobilization strategy aimed

at large-scale change often begins with action a small issue that

concerns many people. For instance, Mahatma Gandhi’s successful overthrow of British rule in India began as a small protest focused on the British tax on salt.

Popovic also argues that a social movement has little chance of

growing if it relies on boring speeches and the usual placard waving

marches. He argues for creating movements that people actually want to

join. OTPOR! succeeded because it was fun, funny, and invented graphic

ways of ridiculing dictator Slobodan Milosevic.

It turned fatalism and passivity into action by making it easy, even

cool, to become a revolutionary; branding itself within hip slogans,

rock music and street theatre. Tina Rosenberg, in Join the Club, How Peer Pressure can Transform the World, shows how movements grow when there is a core of enthusiastic players who encourage others to join them.

Types of social movement

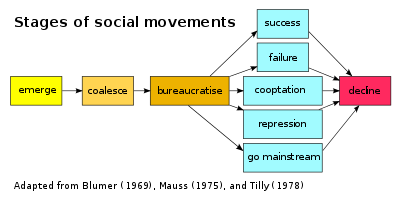

Types of social movements.

Sociologists distinguish between several types of social movement:

- Scope:

- reform movement - movements advocating changing some norms or laws. Examples of such a movement would include a trade union with a goal of increasing workers rights, a green movement advocating a set of ecological laws, or a movement supporting introduction of a capital punishment or the right to abortion. Some reform movements may aim for a change in custom and moral norms, such as condemnation of pornography or proliferation of some religion.

- radical movement - movements dedicated to changing value systems in a fundamental way. Examples would include the Civil Rights Movement which demanded full civil rights and equality under the law to all Americans, regardless of race; the Polish Solidarity (Solidarność) movement which demanded the transformation of a Stalinist political and economic system into a democracy; or the South African shack dwellers' movement Abahlali baseMjondolo which demands the full inclusion of shack dwellers into the life of cities.

- Type of change:

- innovation movement - movements which want to introduce or change particular norms, values, etc. The singularitarianism movement advocating deliberate action to effect and ensure the safety of the technological singularity is an example of an innovation movement.

- conservative movement - movements which want to preserve existing norms, values, etc. For example, the anti-technology 19th century Luddites movement or the modern movement opposing the spread of the genetically modified food could be seen as conservative movements in that they aimed to fight specific technological changes.

- Targets:

- group-focus movements - focused on affecting groups or society in general, for example, advocating the change of the political system. Some of these groups transform into or join a political party, but many remain outside the reformist party political system.

- individual-focused movements - focused on affecting individuals. Most religious movements would fall under this category.

- Methods of work:

- peaceful movements - various movements which use nonviolent means of protest as part of a campaign of nonviolent resistance, also often called civil resistance. The American Civil Rights Movement, Polish Solidarity movement or the nonviolent, civil disobedience-orientated wing of the Indian independence movement would fall into this category.

- violent movements - various movements which resort to violence; they are usually armed and in extreme cases can take a form of a paramilitary or terrorist organization. Examples: the Rote Armee Fraktion, Al-Qaida.

- Old and new:

- old movements - movements for change have existed for many centuries. Most of the oldest recognized movements, dating to late 18th and 19th centuries, fought for specific social groups, such as the working class, peasants, whites, aristocrats, Protestants, men. They were usually centered around some materialistic goals like improving the standard of living or, for example, the political autonomy of the working class.

- new movements - movements which became dominant from the second half of the 20th century. Notable examples include the American civil rights movement, second-wave feminism, gay rights movement, environmentalism and conservation efforts, opposition to mass surveillance, etc. They are usually centered around issues that go beyond but are not separate from class.

- Range:

- global movements - social movements with global (transnational) objectives and goals. Movements such as the first (where Marx and Bakunin met), second, third and fourth internationals, the World Social Forum, the Peoples' Global Action and the anarchist movement seek to change society at a global level.

- local movements - most of the social movements have a local scope. They are focused on local or regional objectives, such as protecting a specific natural area, lobbying for the lowering of tolls in a certain motorway, or preserving a building about to be demolished for gentrification and turning it into a social center.

Identification of supporters

A

difficulty for scholarship of movements is that for most of them,

neither insiders to a movement nor outsiders apply consistent labels or

even descriptive phrases. Unless there is a single leader who does that,

or a formal system of membership agreements, activists will typically

use diverse labels and descriptive phrases that require scholars to

discern when they are referring to the same or similar ideas, declare

similar goals, adopt similar programs of action, and use similar

methods. There can be great differences in the way that is done, to

recognize who is and who is not a member or an allied group:

- Insiders: Often exaggerate the level of support by considering people supporters whose level of activity or support is weak, but also reject those that outsiders might consider supporters because they discredit the cause, or are even seen as adversaries.

- Outsiders: Those not supporters who may tend to either underestimate or overestimate the level or support or activity of elements of a movement, by including or excluding those that insiders would exclude or include.

It is often outsiders rather than insiders that apply the identifying

labels for a movement, which the insiders then may or may not adopt and

use to self-identify. For example, the label for the levellers political movement in 17th-century England was applied to them by their antagonists, as a term of disparagement. Yet admirers of the movement and its aims later came to use the term, and it is the term by which they are known to history.

Caution must always be exercised in any discussion of amorphous

phenomena such as movements to distinguish between the views of insiders

and outsiders, supporters and antagonists, each of whom may have their

own purposes and agendas in characterization or mischaracterization of it.

Dynamics of social movements

Stages of social movements.

Social movements are not eternal. They have a life cycle: they are

created, they grow, they achieve successes or failures and eventually,

they dissolve and cease to exist.

They are more likely to evolve in the time and place which is

friendly to the social movements: hence their evident symbiosis with the

19th century proliferation of ideas like individual rights, freedom of

speech and civil disobedience. Social movements occur in liberal and

authoritarian societies but in different forms. However, there must

always be polarizing differences between groups of people: in case of

'old movements', they were the poverty and wealth gaps.

In case of the 'new movements', they are more likely to be the

differences in customs, ethics and values. Finally, the birth of a

social movement needs what sociologist Neil Smelser calls an initiating event: a particular, individual event that will begin a chain reaction

of events in the given society leading to the creation of a social

movement. For example, the Civil Rights Movement grew on the reaction to

black woman, Rosa Parks,

riding in the whites-only section of the bus (although she was not

acting alone or spontaneously—typically activist leaders lay the

groundwork behind the scenes of interventions designed to spark a

movement). The Polish Solidarity movement, which eventually toppled the communist regimes of Eastern Europe, developed after trade union activist Anna Walentynowicz was fired from work. The South African shack dwellers' movement Abahlali baseMjondolo

grew out of a road blockade in response to the sudden selling off of a

small piece of land promised for housing to a developer. Such an event

is also described as a volcanic model – a social movement is

often created after a large number of people realize that there are

others sharing the same value and desire for a particular social change.

One of the main difficulties facing the emerging social movement

is spreading the very knowledge that it exists. Second is overcoming the

free rider problem

– convincing people to join it, instead of following the mentality 'why

should I trouble myself when others can do it and I can just reap the

benefits after their hard work'.

Many social movements are created around some charismatic leader, i.e. one possessing charismatic authority.

After the social movement is created, there are two likely phases of

recruitment. The first phase will gather the people deeply interested in

the primary goal and ideal of the movement. The second phase, which

will usually come after the given movement had some successes and is

trendy; it would look good on a résumé. People who join in this second phase will likely be the first to leave when the movement suffers any setbacks and failures.

Eventually, the social crisis can be encouraged by outside

elements, like opposition from government or other movements. However,

many movements had survived a failure crisis, being revived by some

hardcore activists even after several decades later.

Social movement theories

Sociologists have developed several theories

related to social movements [Kendall, 2005]. Some of the better-known

approaches are outlined below. Chronologically they include:

- collective behavior/collective action theories (1950s)

- relative deprivation theory (1960s)

- marxist theory (1880s)

- value-added theory (1960s)

- resource mobilization (1970s)

- political process theory (1980s)

- framing theory (1980s) (closely related to social constructionist theory)

- new social movement theory (1980s)

Deprivation theory

Deprivation theory

argues that social movements have their foundations among people who

feel deprived of some good(s) or resource(s). According to this

approach, individuals who are lacking some good, service, or comfort are

more likely to organize a social movement to improve (or defend) their

conditions.

There are two significant problems with this theory. First, since

most people feel deprived at one level or another almost all the time,

the theory has a hard time explaining why the groups that form social

movements do when other people are also deprived. Second, the reasoning

behind this theory is circular – often the only evidence for deprivation

is the social movement. If deprivation is claimed to be the cause but

the only evidence for such is the movement, the reasoning is circular.

Mass society theory

Mass society theory

argues that social movements are made up of individuals in large

societies who feel insignificant or socially detached. Social movements,

according to this theory, provide a sense of empowerment and belonging

that the movement members would otherwise not have.

Very little support has been found for this theory. Aho (1990),

in his study of Idaho Christian Patriotism, did not find that members of

that movement were more likely to have been socially detached. In fact,

the key to joining the movement was having a friend or associate who

was a member of the movement.

Structural strain theory

Social strain theory, also known as value-added theory, proposes six factors that encourage social movement development:

- structural conduciveness - people come to believe their society has problems

- structural strain - people experience deprivation

- growth and spread of a solution - a solution to the problems people are experiencing is proposed and spreads

- precipitating factors - discontent usually requires a catalyst (often a specific event) to turn it into a social movement

- lack of social control - the entity that is to be changed must be at least somewhat open to the change; if the social movement is quickly and powerfully repressed, it may never materialize

- mobilization - this is the actual organizing and active component of the movement; people do what needs to be done

This theory is also subject to circular reasoning as it incorporates,

at least in part, deprivation theory and relies upon it, and

social/structural strain for the underlying motivation of social

movement activism. However, social movement activism is, like in the

case of deprivation theory, often the only indication that there was

strain or deprivation.

Resource mobilization theory

Resource mobilization theory

emphasizes the importance of resources in social movement development

and success. Resources are understood here to include: knowledge, money,

media, labor, solidarity, legitimacy, and internal and external support

from power elite. The theory argues that social movements develop when

individuals with grievances are able to mobilize sufficient resources to

take action.The emphasis on resources offers an explanation why some

discontented/deprived individuals are able to organize while others are

not.

In contrast to earlier collective behavior

perspectives on social movements—which emphasized the role of

exceptional levels of deprivation, grievance, or social strain in

motivating mass protest—Resource Mobilization perspectives hold "that

there is always enough discontent in any society to supply the

grass-roots support for a movement if the movement is effectively

organized and has at its disposal the power and resources of some

established elite group" Movement emergence is contingent upon the aggregation of resources by

social movement entrepreneurs and movement organizations, who use these

resources to turn collective dissent in to political pressure.

Members are recruited through networks; commitment is maintained by

building a collective identity, and through interpersonal relationships.

Resource Mobilization Theory views social movement activity as

"politics by other means": a rational and strategic effort by ordinary

people to change society or politics.

The form of the resources shapes the activities of the movement (e.g.,

access to a TV station will result in the extensive use TV media).

Movements develop in contingent opportunity structures that

influence their efforts to mobilize; and each movement's response to the

opportunity structures depends on the movement's organization and

resources.

Critics of this theory argue that there is too much of an

emphasis on resources, especially financial resources. Some movements

are effective without an influx of money and are more dependent upon the

movement members for time and labor (e.g., the civil rights movement in

the U.S.).

Political process theory

Political process theory is similar to resource mobilization in many regards, but tends to emphasize a different component of social structure that is important for social movement development: political opportunities.

Political process theory argues that there are three vital components

for movement formation: insurgent consciousness, organizational

strength, and political opportunities.

Insurgent consciousness refers back to the ideas of deprivation

and grievances. The idea is that certain members of society feel like

they are being mistreated or that somehow the system is unjust. The

insurgent consciousness is the collective sense of injustice that

movement members (or potential movement members) feel and serves as the

motivation for movement organization.

Photo taken at the 2005 U.S. Presidential inauguration protest.

Organizational strength falls inline with resource-mobilization

theory, arguing that in order for a social movement to organize it must

have strong leadership and sufficient resources.

Political opportunity refers to the receptivity or vulnerability

of the existing political system to challenge. This vulnerability can be

the result of any of the following (or a combination thereof):

- growth of political pluralism

- decline in effectiveness of repression

- elite disunity; the leading factions are internally fragmented

- a broadening of access to institutional participation in political processes

- support of organized opposition by elites

One of the advantages of the political process theory is that it

addresses the issue of timing or emergence of social movements. Some

groups may have the insurgent consciousness and resources to mobilize,

but because political opportunities are closed, they will not have any

success. The theory, then, argues that all three of these components are

important.

Critics of the political process theory and resource-mobilization

theory point out that neither theory discusses movement culture to any

great degree. This has presented culture theorists an opportunity to

expound on the importance of culture.

One advance on the political process theory is the political mediation model,

which outlines the way in which the political context facing movement

actors intersects with the strategic choices that movements make. An

additional strength of this model is that it can look at the outcomes of

social movements not only in terms of success or failure but also in

terms of consequences (whether intentional or unintentional, positive or

negative) and in terms of collective benefits.

Framing perspective

Reflecting the cultural turn

in the social sciences and humanities more broadly, recent strains of

social movement theory and research add to the largely structural

concerns seen in the resource mobilization and political process

theories by emphasizing the cultural and psychological aspects of social

movement processes, such as collectively shared interpretations and

beliefs, ideologies, values and other meanings about the world. In doing

so, this general cultural approach also attempts to address the free-rider problem. One particularly successful take on some such cultural dimensions is manifested in the framing perspective on social movements.

While both resource mobilization theory and political process

theory include, or at least accept, the idea that certain shared

understandings of, for example, perceived unjust societal conditions

must exist for mobilization to occur at all, this is not explicitly

problematized within those approaches. The framing perspective has

brought such shared understandings to the forefront of the attempt to

understand movement creation and existence by, e.g., arguing that, in

order for social movements to successfully mobilize individuals, they

must develop an injustice frame. An injustice frame is a

collection of ideas and symbols that illustrate both how significant the

problem is as well as what the movement can do to alleviate it,

- Like a picture frame, an issue frame marks off some part of the world. Like a building frame, it holds things together. It provides coherence to an array of symbols, images, and arguments, linking them through an underlying organizing idea that suggests what is essential - what consequences and values are at stake. We do not see the frame directly, but infer its presence by its characteristic expressions and language. Each frame gives the advantage to certain ways of talking and thinking, while it places others out of the picture.

Important characteristics of the injustice frames include:

- Facts take on their meaning by being embedded in frames, which render them relevant and significant or irrelevant and trivial.

- People carry around multiple frames in their heads.

- Successful reframing involves the ability to enter into the worldview of our adversaries.

- All frames contain implicit or explicit appeals to moral principles.

In emphasizing the injustice frame, culture theory also addresses the

free-rider problem. The free-rider problem refers to the idea that

people will not be motivated to participate in a social movement that

will use up their personal resources (e.g., time, money, etc.) if they

can still receive the benefits without participating. In other words, if

person X knows that movement Y is working to improve environmental

conditions in his neighborhood, he is presented with a choice: join or

not join the movement. If he believes the movement will succeed without

him, he can avoid participation in the movement, save his resources, and

still reap the benefits - this is free-riding. A significant

problem for social movement theory has been to explain why people join

movements if they believe the movement can/will succeed without their

contribution. Culture theory argues that, in conjunction with social

networks being an important contact tool, the injustice frame will

provide the motivation for people to contribute to the movement.

Framing processes includes three separate components:

- Diagnostic frame: the movement organization frames what is the problem or what they are critiquing

- Prognostic frame: the movement organization frames what is the desirable solution to the problem

- Motivational frame: the movement organization frames a "call to arms" by suggesting and encouraging that people take action to solve the problem

Social movement and social networking

For

more than ten years, social movement groups have been using the

Internet to accomplish organizational goals. It has been argued that the

Internet helps to increase the speed, reach and effectiveness of social

movement-related communication as well as mobilization efforts, and as a

result, it has been suggested that the Internet has had a positive

impact on the social movements in general.

Many discussions have been generated recently on the topic of

social networking and the effect it may play on the formation and

mobilization of social movement. For example, the emergence of the Coffee Party first appeared on the social networking site, Facebook. The party has continued to gather membership and support through that site and file sharing sites, such as Flickr. The 2009–2010 Iranian election protests

also demonstrated how social networking sites are making the

mobilization of large numbers of people quicker and easier. Iranians

were able to organize and speak out against the election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad by using sites such as Twitter and Facebook. This in turn prompted widespread government censorship of the web and social networking sites.

The sociological study of social movements is quite new. The

traditional view of movements often perceived them as chaotic and

disorganized, treating activism as a threat to the social order.

The activism experienced in the 1960s and 1970s shuffled in a new world

opinion about the subject. Models were now introduced to understand the

organizational and structural powers embedded in social movements.