| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Aluminium | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation |

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative name | aluminum (U.S., Canada) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery gray metallic | |||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar, std(Al) | 26.9815384(3) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Aluminium in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 13 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 13 (boron group) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | |||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | post-transition metal, sometimes considered a metalloid | |||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ne] 3s2 3p1 | |||||||||||||||||||

Electrons per shell

| 2, 8, 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | |||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 933.47 K (660.32 °C, 1220.58 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2743 K (2470 °C, 4478 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 2.70 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 2.375 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 10.71 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 284 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.20 J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, −1, +1, +2, +3 (an amphoteric oxide) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.61 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 143 pm | |||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 121±4 pm | |||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 184 pm | |||||||||||||||||||

| Spectral lines of aluminium | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | |||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | (rolled) 5000 m/s (at r.t.) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 23.1 µm/(m·K) (at 25 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 237 W/(m·K) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 26.5 nΩ·m (at 20 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic | |||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic susceptibility | +16.5·10−6 cm3/mol | |||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 70 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 26 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 76 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.35 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 2.75 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 160–350 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 160–550 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7429-90-5 | |||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after alumina (aluminium oxide), itself named after mineral alum | |||||||||||||||||||

| Prediction | Antoine Lavoisier (1782) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Hans Christian Ørsted (1824) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Named by | Humphry Davy (1812) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Main isotopes of aluminium | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Aluminium or aluminum is a chemical element with symbol Al and atomic number 13. It is a silvery-white, soft, nonmagnetic and ductile metal in the boron group. By mass, aluminium makes up about 8% of the Earth's crust; it is the third most abundant element after oxygen and silicon and the most abundant metal in the crust, though it is less common in the mantle below. The chief ore of aluminium is bauxite. Aluminium metal is so chemically reactive that native specimens are rare and limited to extreme reducing environments. Instead, it is found combined in over 270 different minerals.

Aluminium is remarkable for its low density and its ability to resist corrosion through the phenomenon of passivation. Aluminium and its alloys are vital to the aerospace industry and important in transportation and building industries, such as building facades and window frames. The oxides and sulfates are the most useful compounds of aluminium.

Despite its prevalence in the environment, no known form of life uses aluminium salts metabolically, but aluminium is well tolerated by plants and animals. Because of these salts' abundance, the potential for a biological role for them is of continuing interest, and studies continue.

Physical characteristics

Nuclei and isotopes

Of aluminium isotopes, only 27Alis stable. This is consistent with aluminium having an odd atomic number. It is the only aluminium isotope that has existed on Earth in its current form since the creation of the planet. Very nearly all the element on Earth is present as this isotope, which makes aluminium a mononuclidic element and means that its standard atomic weight practically equates to that of the isotope. The standard atomic weight of aluminium is low in comparison with many other metals, which has consequences for the element's properties.

All other isotopes of aluminium are radioactive. The most stable of these is 26Al (half-life 720,000 years) and therefore could not have survived since the formation of the planet. However, 26Al is produced from argon in the atmosphere by spallation caused by cosmic ray protons. The ratio of 26Al to 10Be has been used for radiodating of geological processes over 105 to 106 year time scales, in particular transport, deposition, sediment storage, burial times, and erosion. Most meteorite scientists believe that the energy released by the decay of 26Al was responsible for the melting and differentiation of some asteroids after their formation 4.55 billion years ago.

The remaining isotopes of aluminium, with mass numbers ranging from 21 to 43, all have half-lives well under an hour. Three metastable states are known, all with half-lives under a minute.

Electron shell

An aluminium atom has 13 electrons, arranged in an electron configuration of [Ne]3s23p1, with three electrons beyond a stable noble gas configuration. Accordingly, the combined first three ionization energies of aluminium are far lower than the fourth ionization energy alone. Aluminium can relatively easily surrender its three outermost electrons in many chemical reactions. The electronegativity of aluminium is 1.61 (Pauling scale).

A free aluminium atom has a radius of 143 pm. With the three outermost electrons removed, the radius shrinks to 39 pm for a 4-coordinated atom or 53.5 pm for a 6-coordinated atom. At standard temperature and pressure, aluminium atoms (when not affected by atoms of other elements) form a face-centered cubic crystal system bound by metallic bonding

provided by atoms' outermost electrons; hence aluminium (at these

conditions) is a metal. This crystal system is shared by some other

metals, such as lead and copper; the size of a unit cell of aluminium is comparable to that of those other metals.

Bulk

Aluminium metal, when in quantity, is very shiny and resembles silver because it preferentially absorbs far ultraviolet radiation while reflecting all visible light so it does not impart any color to reflected light, unlike the reflectance spectra of copper and gold. Another important characteristic of aluminium is its low density, 2.70 g/cm3. Aluminium is a relatively soft, durable, lightweight, ductile, and malleable

with appearance ranging from silvery to dull gray, depending on the

surface roughness. It is nonmagnetic and does not easily ignite. A fresh

film of aluminium serves as a good reflector (approximately 92%) of visible light and an excellent reflector (as much as 98%) of medium and far infrared radiation. The yield strength of pure aluminium is 7–11 MPa, while aluminium alloys have yield strengths ranging from 200 MPa to 600 MPa. Aluminium has about one-third the density and stiffness of steel. It is easily machined, cast, drawn and extruded.

Aluminium atoms are arranged in a face-centered cubic (fcc) structure. Aluminium has a stacking-fault energy of approximately 200 mJ/m2.

Aluminium is a good thermal and electrical conductor, having 59% the conductivity of copper, both thermal and electrical, while having only 30% of copper's density. Aluminium is capable of superconductivity, with a superconducting critical temperature of 1.2 kelvin and a critical magnetic field of about 100 gauss (10 milliteslas).

Aluminium is the most common material for the fabrication of superconducting qubits.

Etched surface from a high purity (99.9998%) aluminium bar, size 55×37 mm

Chemistry

Aluminium's corrosion resistance can be excellent due to a thin surface layer of aluminium oxide that forms when the bare metal is exposed to air, effectively preventing further oxidation, in a process termed passivation. The strongest aluminium alloys are less corrosion resistant due to galvanic reactions with alloyed copper. This corrosion resistance is greatly reduced by aqueous salts, particularly in the presence of dissimilar metals.

In highly acidic solutions, aluminium reacts with water to form hydrogen, and in highly alkaline ones to form aluminates—protective passivation under these conditions is negligible. Primarily because it is corroded by dissolved chlorides, such as common sodium chloride, household plumbing is never made from aluminium.

However, because of its general resistance to corrosion,

aluminium is one of the few metals that retains silvery reflectance in

finely powdered form, making it an important component of silver-colored paints. Aluminium mirror finish has the highest reflectance of any metal in the 200–400 nm (UV) and the 3,000–10,000 nm (far IR) regions; in the 400–700 nm visible range it is slightly outperformed by tin and silver and in the 700–3000 nm (near IR) by silver, gold, and copper.

Aluminium is oxidized by water at temperatures below 280 °C to produce hydrogen, aluminium hydroxide and heat:

- 2 Al + 6 H2O → 2 Al(OH)3 + 3 H2

This conversion is of interest for the production of hydrogen.

However, commercial application of this fact has challenges in

circumventing the passivating oxide layer, which inhibits the reaction,

and in storing the energy required to regenerate the aluminium metal.

Inorganic compounds

The vast majority of compounds, including all Al-containing minerals

and all commercially significant aluminium compounds, feature aluminium

in the oxidation state 3+. The coordination number of such compounds varies, but generally Al3+ is six-coordinate or tetracoordinate. Almost all compounds of aluminium(III) are colorless.

All four trihalides are well known. Unlike the structures of the three heavier trihalides, aluminium fluoride (AlF3) features six-coordinate Al. The octahedral coordination environment for AlF3 is related to the compactness of the fluoride ion, six of which can fit around the small Al3+ center. AlF3

sublimes (with cracking) at 1,291 °C (2,356 °F). With heavier halides,

the coordination numbers are lower. The other trihalides are dimeric or polymeric

with tetrahedral Al centers. These materials are prepared by treating

aluminium metal with the halogen, although other methods exist. Acidification of the oxides or hydroxides

affords hydrates. In aqueous solution, the halides often form mixtures,

generally containing six-coordinate Al centers that feature both halide

and aquo ligands. When aluminium and fluoride are together in aqueous solution, they readily form complex ions such as [AlF(H

2O)

5]2+, AlF

3(H

2O)

3, and [AlF

6]3−. In the case of chloride, polyaluminium clusters are formed such as [Al13O4(OH)24(H2O)12]7+.

2O)

5]2+, AlF

3(H

2O)

3, and [AlF

6]3−. In the case of chloride, polyaluminium clusters are formed such as [Al13O4(OH)24(H2O)12]7+.

Aluminium hydrolysis as a function of pH. Coordinated water molecules are omitted.

Aluminium forms one stable oxide with the chemical formula Al2O3. It can be found in nature in the mineral corundum. Aluminium oxide is also commonly called alumina. Sapphire and ruby are impure corundum contaminated with trace amounts of other metals. The two oxide-hydroxides, AlO(OH), are boehmite and diaspore. There are three trihydroxides: bayerite, gibbsite, and nordstrandite, which differ in their crystalline structure (polymorphs).

Most are produced from ores by a variety of wet processes using acid

and base. Heating the hydroxides leads to formation of corundum. These

materials are of central importance to the production of aluminium and

are themselves extremely useful.

Aluminium carbide (Al4C3)

is made by heating a mixture of the elements above 1,000 °C (1,832 °F).

The pale yellow crystals consist of tetrahedral aluminium centers. It

reacts with water or dilute acids to give methane. The acetylide, Al2(C2)3, is made by passing acetylene over heated aluminium.

Aluminium nitride

(AlN) is the only nitride known for aluminium. Unlike the oxides, it

features tetrahedral Al centers. It can be made from the elements at

800 °C (1,472 °F). It is air-stable material with a usefully high thermal conductivity. Aluminium phosphide (AlP) is made similarly; it hydrolyses to give phosphine:

- AlP + 3 H2O → Al(OH)3 + PH3

Rarer oxidation states

Although the great majority of aluminium compounds feature Al3+ centers, compounds with lower oxidation states are known and sometime of significance as precursors to the Al3+ species.

Aluminium(I)

AlF, AlCl and AlBr exist in the gaseous phase when the trihalide is heated with aluminium. The composition AlI is unstable at room temperature, converting to triiodide:

A stable derivative of aluminium monoiodide is the cyclic adduct formed with triethylamine, Al4I4(NEt3)4. Also of theoretical interest but only of fleeting existence are Al2O and Al2S. Al2O is made by heating the normal oxide, Al2O3, with silicon at 1,800 °C (3,272 °F) in a vacuum. Such materials quickly disproportionate to the starting materials.

Aluminium(II)

Very simple Al(II) compounds are invoked or observed in the reactions of Al metal with oxidants. For example, aluminium monoxide, AlO, has been detected in the gas phase after explosion and in stellar absorption spectra. More thoroughly investigated are compounds of the formula R4Al2 which contain an Al-Al bond and where R is a large organic ligand.

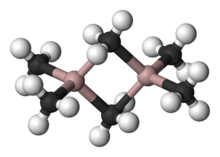

Structure of trimethylaluminium, a compound that features five-coordinate carbon.

A variety of compounds of empirical formula AlR3 and AlR1.5Cl1.5 exist.

These species usually feature tetrahedral Al centers formed by

dimerization with some R or Cl bridging between both Al atoms, e.g. "trimethylaluminium" has the formula Al2(CH3)6 (see figure). With large organic groups, triorganoaluminium compounds exist as three-coordinate monomers, such as triisobutylaluminium. Such compounds are widely used in industrial chemistry, despite the fact that they are often highly pyrophoric. Few analogues exist between organoaluminium and organoboron compounds other than large organic groups.

The industrially important aluminium hydride is lithium aluminium hydride (LiAlH4), which is used in as a reducing agent in organic chemistry. It can be produced from lithium hydride and aluminium trichloride:

- 4 LiH + AlCl3 → LiAlH4 + 3 LiCl

Several useful derivatives of LiAlH4 are known, e.g. sodium bis(2-methoxyethoxy)dihydridoaluminate. The simplest hydride, aluminium hydride or alane, remains a laboratory curiosity. It is a polymer with the formula (AlH3)n, in contrast to the corresponding boron hydride that is a dimer with the formula (BH3)2.

Natural occurrence

In space

Aluminium's per-particle abundance in the Solar System is 3.15 ppm (parts per million).

It is the twelfth most abundant of all elements and third most abundant

among the elements that have odd atomic numbers, after hydrogen and

nitrogen. The only stable isotope of aluminium, 27Al,

is the eighteenth most abundant nucleus in the Universe. It is created

almost entirely after fusion of carbon in massive stars that will later

become Type II supernovae: this fusion creates 26Mg, which, upon capturing free protons and neutrons becomes aluminium. Some smaller quantities of 27Al are created in hydrogen burning shells of evolved stars, where 26Mg can capture free protons. Essentially all aluminium now in existence is 27Al; 26Al was present in the early Solar System but is currently extinct. However, the trace quantities of 26Al that do exist are the most common gamma ray emitter in the interstellar gas.

On Earth

Bauxite, a major aluminium ore. The red-brown color is due to the presence of iron oxide minerals.

Overall, the Earth is about 1.59% aluminium by mass (seventh in abundance by mass).

Aluminium occurs in greater proportion in the Earth than in the

Universe because aluminium easily forms the oxide and becomes bound into

rocks and aluminium stays in the Earth's crust while less reactive metals sink to the core.

In the Earth's crust, aluminium is the most abundant (8.3% by mass)

metallic element and the third most abundant of all elements (after

oxygen and silicon). A large number of silicates in the Earth's crust contain aluminium. In contrast, the Earth's mantle is only 2.38% aluminium by mass.

Because of its strong affinity for oxygen, aluminium is almost

never found in the elemental state; instead it is found in oxides or

silicates. Feldspars, the most common group of minerals in the Earth's crust, are aluminosilicates. Aluminium also occurs in the minerals beryl, cryolite, garnet, spinel, and turquoise. Impurities in Al2O3, such as chromium and iron, yield the gemstones ruby and sapphire, respectively. Native aluminium metal can only be found as a minor phase in low oxygen fugacity environments, such as the interiors of certain volcanoes. Native aluminium has been reported in cold seeps in the northeastern continental slope of the South China Sea. It is possible that these deposits resulted from bacterial reduction of tetrahydroxoaluminate Al(OH)4−.

Although aluminium is a common and widespread element, not all

aluminium minerals are economically viable sources of the metal. Almost

all metallic aluminium is produced from the ore bauxite (AlOx(OH)3–2x). Bauxite occurs as a weathering product of low iron and silica bedrock in tropical climatic conditions. In 2017, most bauxite was mined in Australia, China, Guinea, and India.

History

Friedrich Wöhler, the chemist who first thoroughly described metallic elemental aluminium

The history of aluminium has been shaped by usage of alum. The first written record of alum, made by Greek historian Herodotus, dates back to the 5th century BCE. The ancients are known to have used alum as a dyeing mordant and for city defense. After the Crusades, alum, an indispensable good in the European fabric industry, was a subject of international commerce; it was imported to Europe from the eastern Mediterranean until the mid-15th century.

The nature of alum remained unknown. Around 1530, Swiss physician Paracelsus suggested alum was a salt of an earth of alum. In 1595, German doctor and chemist Andreas Libavius experimentally confirmed this; In 1722, German chemist Friedrich Hoffmann announced his belief that the base of alum was a distinct earth. In 1754, German chemist Andreas Sigismund Marggraf synthesized alumina by boiling clay in sulfuric acid and subsequently adding potash.

Attempts to produce aluminium metal date back to 1760. The first successful attempt, however, was completed in 1824 by Danish physicist and chemist Hans Christian Ørsted. He reacted anhydrous aluminium chloride with potassium amalgam, yielding a lump of metal looking similar to tin. He presented his results and demonstrated a sample of the new metal in 1825. In 1827, German chemist Friedrich Wöhler repeated Ørsted's experiments but did not identify any aluminium. (The reason for this inconsistency was only discovered in 1921.)

He conducted a similar experiment in 1827 by mixing anhydrous aluminium

chloride with potassium and produced a powder of aluminium. In 1845, he was able to produce small pieces of the metal and described some physical properties of this metal. For many years thereafter, Wöhler was credited as the discoverer of aluminium. As Wöhler's method could not yield great quantities of aluminium, the metal remained rare; its cost exceeded that of gold.

The statue of Anteros in Piccadilly Circus, London, was made in 1893 and is one of the first statues cast in aluminium.

French chemist Henri Etienne Sainte-Claire Deville announced an industrial method of aluminium production in 1854 at the Paris Academy of Sciences.

Aluminium trichloride could be reduced by sodium, which was more

convenient and less expensive than potassium, which Wöhler had used. In 1856, Deville along with companions established the world's first industrial production of aluminium. From 1855 to 1859, the price of aluminium dropped by an order of magnitude, from US$500 to $40 per kilogram. Even then, aluminium was still not of great purity and produced aluminium differed in properties by sample.

The first industrial large-scale production method was independently developed in 1886 by French engineer Paul Héroult and American engineer Charles Martin Hall; it is now known as the Hall–Héroult process. The Hall–Héroult process converts alumina into the metal. Austrian chemist Carl Joseph Bayer discovered a way of purifying bauxite to yield alumina, now known as the Bayer process, in 1889. Modern production of the aluminium metal is based on the Bayer and Hall–Héroult processes.

Prices of aluminium dropped and aluminium became widely used in

jewelry, everyday items, eyeglass frames, optical instruments,

tableware, and foil

in the 1890s and early 20th century. Aluminium's ability to form hard

yet light alloys with other metals provided the metal many uses at the

time. During World War I, major governments demanded large shipments of aluminium for light strong airframes.

By the mid-20th century, aluminium had become a part of everyday life and an essential component of housewares.

During the mid-20th century, aluminium emerged as a civil engineering

material, with building applications in both basic construction and

interior finish work, and increasingly being used in military engineering, for both airplanes and land armor vehicle engines. Earth's first artificial satellite,

launched in 1957, consisted of two separate aluminium semi-spheres

joined together and all subsequent space vehicles have been made of

aluminium. The aluminium can was invented in 1956 and employed as a storage for drinks in 1958.

World production of aluminium since 1900

Throughout the 20th century, the production of aluminium rose

rapidly: while the world production of aluminium in 1900 was 6,800

metric tons, the annual production first exceeded 100,000 metric tons in

1916; 1,000,000 tons in 1941; 10,000,000 tons in 1971. In the 1970s, the increased demand for aluminium made it an exchange commodity; it entered the London Metal Exchange, the oldest industrial metal exchange in the world, in 1978. The output continued to grow: the annual production of aluminium exceeded 50,000,000 metric tons in 2013.

The real price for aluminium declined from $14,000 per metric ton in 1900 to $2,340 in 1948 (in 1998 United States dollars).

Extraction and processing costs were lowered over technological

progress and the scale of the economies. However, the need to exploit

lower-grade poorer quality deposits and the use of fast increasing input

costs (above all, energy) increased the net cost of aluminium; the real price began to grow in the 1970s with the rise of energy cost. Production moved from the industrialized countries to countries where production was cheaper.

Production costs in the late 20th century changed because of advances

in technology, lower energy prices, exchange rates of the United States

dollar, and alumina prices. The BRIC

countries' combined share grew in the first decade of the 21st century

from 32.6% to 56.5% in primary production and 21.4% to 47.8% in primary

consumption.

China is accumulating an especially large share of world's production

thanks to abundance of resources, cheap energy, and governmental

stimuli; it also increased its consumption share from 2% in 1972 to 40% in 2010.

In the United States, Western Europe, and Japan, most aluminium was

consumed in transportation, engineering, construction, and packaging.

Etymology

Aluminium is named after alumina, or aluminium oxide in modern

nomenclature. The word "alumina" comes from "alum", the mineral from

which it was collected. The word "alum" comes from alumen, a Latin word meaning "bitter salt". The word alumen stems from the Proto-Indo-European root *alu- meaning "bitter" or "beer".

1897 American advertisement featuring the aluminum spelling

British chemist Humphry Davy,

who performed a number of experiments aimed to synthesize the metal, is

credited as the person who named the element. In 1808, he suggested the

metal be named alumium.

This suggestion was criticized by contemporary chemists from France,

Germany, and Sweden, who insisted the metal should be named for the

oxide, alumina, from which it would be isolated. In 1812, Davy chose aluminum, thus producing the modern name. However, it is spelled and pronounced differently outside of North America: aluminum is in use in the U.S. and Canada while aluminium is in use elsewhere.

Spelling

The -ium suffix followed the precedent set in other newly discovered elements of the time: potassium, sodium, magnesium, calcium, and strontium (all of which Davy isolated himself). Nevertheless, element names ending in -um were known at the time; for example, platinum (known to Europeans since the 16th century), molybdenum (discovered in 1778), and tantalum (discovered in 1802). The -um suffix is consistent with the universal spelling alumina for the oxide (as opposed to aluminia); compare to lanthana, the oxide of lanthanum, and magnesia, ceria, and thoria, the oxides of magnesium, cerium, and thorium, respectively.

In 1812, British scientist Thomas Young wrote an anonymous review of Davy's book, in which he objected to aluminum and proposed the name aluminium: "for so we shall take the liberty of writing the word, in preference to aluminum, which has a less classical sound." This name did catch on: while the -um spelling was occasionally used in Britain, the American scientific language used -ium from the start. Most scientists used -ium throughout the world in the 19th century; it still remains the standard in most other languages. In 1828, American lexicographer Noah Webster used exclusively the aluminum spelling in his American Dictionary of the English Language. In the 1830s, the -um

spelling started to gain usage in the United States; by the 1860s, it

had become the more common spelling there outside science. In 1892, Hall used the -um spelling in his advertising handbill for his new electrolytic method of producing the metal, despite his constant use of the -ium spelling in all the patents he filed between 1886 and 1903. It was subsequently suggested this was a typo rather than intended. By 1890, both spellings had been common in the U.S. overall, the -ium spelling being slightly more common; by 1895, the situation had reversed; by 1900, aluminum had become twice as common as aluminium; during the following decade, the -um spelling dominated American usage. In 1925, the American Chemical Society adopted this spelling.

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) adopted aluminium as the standard international name for the element in 1990. In 1993, they recognized aluminum as an acceptable variant; the same is true for the most recent 2005 edition of the IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry. IUPAC official publications use the -ium spelling as primary but list both where appropriate.

Production and refinement

Bayer process

Bauxite is converted to aluminium oxide by the Bayer process. Bauxite

is blended for uniform composition and then is ground. The resulting slurry is mixed with a hot solution of sodium hydroxide;

the mixture is then treated in a digester vessel at a pressure well

above atmospheric, dissolving the aluminium hydroxide in bauxite while

converting impurities into a relatively insoluble compounds:

After this reaction, the slurry is at a temperature above its

atmospheric boiling point. It is cooled by removing steam as pressure is

reduced. The bauxite residue is separated from the solution and

discarded. The solution, free of solids, is seeded with small crystals

of aluminium hydroxide; this causes decomposition of the [Al(OH)4]−

ions to aluminium hydroxide. After about half of aluminium has

precipitated, the mixture is sent to classifiers. Small crystals of

aluminium hydroxide are collected to serve as seeding agents; coarse

particles are converted to aluminium oxide by heating; excess solution

is removed by evaporation, (if needed) purified, and recycled.

Hall–Héroult process

The conversion of alumina to aluminium metal is achieved by the Hall–Héroult process. In this energy-intensive process, a solution of alumina in a molten (950 and 980 °C (1,740 and 1,800 °F)) mixture of cryolite (Na3AlF6) with calcium fluoride is electrolyzed

to produce metallic aluminium. The liquid aluminium metal sinks to the

bottom of the solution and is tapped off, and usually cast into large

blocks called aluminium billets for further processing.

Extrusion billets of aluminium

Anodes of the electrolysis cell are made of carbon—the most resistant

material against fluoride corrosion—and either bake at the process or

are prebaked. The former, also called Söderberg anodes, are less

power-efficient and fumes released during baking are costly to collect,

which is why they are being replaced by prebaked anodes even though they

save the power, energy, and labor to prebake the cathodes. Carbon for

anodes should be preferably pure so that neither aluminium nor the

electrolyte is contaminated with ash. Despite carbon's resistivity

against corrosion, it is still consumed at a rate of 0.4–0.5 kg per each

kilogram of produced aluminium. Cathodes are made of anthracite; high purity for them is not required because impurities leach

only very slowly. Cathode is consumed at a rate of 0.02–0.04 kg per

each kilogram of produced aluminium. A cell is usually a terminated

after 2–6 years following a failure of the cathode.

The Hall–Heroult process produces aluminium with a purity of above 99%. Further purification can be done by the Hoopes process.

This process involves the electrolysis of molten aluminium with a

sodium, barium, and aluminium fluoride electrolyte. The resulting

aluminium has a purity of 99.99%.

Electric power represents about 20 to 40% of the cost of

producing aluminium, depending on the location of the smelter. Aluminium

production consumes roughly 5% of electricity generated in the United

States.

Because of this, alternatives to the Hall–Héroult process have been

researched, but none has turned out to be economically feasible.

Common

bins for recyclable waste along with a bin for unrecyclable waste. The

bin with a yellow top is labeled "aluminum". Rhodes, Greece.

Recycling

Recovery of the metal through recycling

has become an important task of the aluminium industry. Recycling was a

low-profile activity until the late 1960s, when the growing use of

aluminium beverage cans brought it to public awareness.

Recycling involves melting the scrap, a process that requires only 5%

of the energy used to produce aluminium from ore, though a significant

part (up to 15% of the input material) is lost as dross (ash-like oxide). An aluminium stack melter produces significantly less dross, with values reported below 1%.

White dross from primary aluminium production and from secondary

recycling operations still contains useful quantities of aluminium that

can be extracted industrially.

The process produces aluminium billets, together with a highly complex

waste material. This waste is difficult to manage. It reacts with water,

releasing a mixture of gases (including, among others, hydrogen, acetylene, and ammonia), which spontaneously ignites on contact with air;

contact with damp air results in the release of copious quantities of

ammonia gas. Despite these difficulties, the waste is used as a filler

in asphalt and concrete.

Applications

Aluminium-bodied Austin A40 Sports (c. 1951)

Metal

Aluminium is the most widely used non-ferrous metal. The global production of aluminium in 2016 was 58.8 million metric tons. It exceeded that of any other metal except iron (1,231 million metric tons).

Aluminium is almost always alloyed, which markedly improves its mechanical properties, especially when tempered. For example, the common aluminium foils and beverage cans are alloys of 92% to 99% aluminium. The main alloying agents are copper, zinc, magnesium, manganese, and silicon (e.g., duralumin) with the levels of other metals in a few percent by weight.

The major uses for aluminium metal are in:

- Transportation (automobiles, aircraft, trucks, railway cars, marine vessels, bicycles, spacecraft, etc.). Aluminium is used because of its low density;

- Packaging (cans, foil, frame etc.). Aluminium is used because it is non-toxic, non-adsorptive, and splinter-proof;

- Building and construction (windows, doors, siding, building wire, sheathing, roofing, etc.). Since steel is cheaper, aluminium is used when lightness, corrosion resistance, or engineering features are important;

- Electricity-related uses (conductor alloys, motors and generators, transformers, capacitors, etc.). Aluminium is used because it is relatively cheap, highly conductive, has adequate mechanical strength and low density, and resists corrosion;

- A wide range of household items, from cooking utensils to furniture. Low density, good appearance, ease of fabrication, and durability are the key factors of aluminium usage;

- Machinery and equipment (processing equipment, pipes, tools). Aluminium is used because of its corrosion resistance, non-pyrophoricity, and mechanical strength.

Compounds

The great majority (about 90%) of aluminium oxide is converted to metallic aluminium. Being a very hard material (Mohs hardness 9), alumina is widely used as an abrasive; being extraordinarily chemically inert, it is useful in highly reactive environments such as high pressure sodium lamps. Aluminium oxide is commonly used as a catalyst for industrial processes; e.g. the Claus process to convert hydrogen sulfide to sulfur in refineries and to alkylate amines. Many industrial catalysts are supported by alumina, meaning that the expensive catalyst material is dispersed over a surface of the inert alumina. Another principal use is as a drying agent or absorbent.

Laser deposition of alumina on a substrate

Several sulfates of aluminium have industrial and commercial application. Aluminium sulfate (in its hydrate form) is produced on the annual scale of several millions of metric tons. About two-thirds is consumed in water treatment. The next major application is in the manufacture of paper. It is also used as a mordant in dyeing, in pickling seeds, deodorizing of mineral oils, in leather tanning, and in production of other aluminium compounds. Two kinds of alum, ammonium alum and potassium alum, were formerly used as mordants and in leather tanning, but their use has significantly declined following availability of high-purity aluminium sulfate. Anhydrous aluminium chloride

is used as a catalyst in chemical and petrochemical industries, the

dyeing industry, and in synthesis of various inorganic and organic

compounds. Aluminium hydroxychlorides are used in purifying water, in the paper industry, and as antiperspirants. Sodium aluminate is used in treating water and as an accelerator of solidification of cement.

Many aluminium compounds have niche applications, for example:

- Aluminium acetate in solution is used as an astringent.

- Aluminium phosphate is used in the manufacture of glass, ceramic, pulp and paper products, cosmetics, paints, varnishes, and in dental cement.

- Aluminium hydroxide is used as an antacid, and mordant; it is used also in water purification, the manufacture of glass and ceramics, and in the waterproofing of fabrics.

- Lithium aluminium hydride is a powerful reducing agent used in organic chemistry.

- Organoaluminiums are used as Lewis acids and cocatalysts.

- Methylaluminoxane is a cocatalyst for Ziegler–Natta olefin polymerization to produce vinyl polymers such as polyethene.

- Aqueous aluminium ions (such as aqueous aluminium sulfate) are used to treat against fish parasites such as Gyrodactylus salaris.

- In many vaccines, certain aluminium salts serve as an immune adjuvant (immune response booster) to allow the protein in the vaccine to achieve sufficient potency as an immune stimulant.

Biology

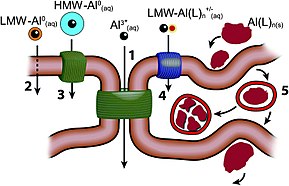

Schematic of aluminium absorption by human skin.

Despite its widespread occurrence in the Earth's crust, aluminium has

no known function in biology. Aluminium salts are remarkably nontoxic, aluminium sulfate having an LD50 of 6207 mg/kg (oral, mouse), which corresponds to 500 grams for an 80 kg (180 lb) person.

Toxicity

In most people, aluminium is not as toxic as heavy metals. Aluminium is classified as a non-carcinogen by the United States Department of Health and Human Services. There is little evidence that normal exposure to aluminium presents a risk to healthy adult, and there is evidence of no toxicity if it is consumed in amounts not greater than 40 mg/day per kg of body mass. Most aluminium consumed will leave the body in feces; the small part of it that enters the body, will be excreted via urine. Aluminium that does stay in the body is accumulated in, above all, bone; and apart from that, in brain, liver, and kidney.

Aluminium metal cannot pass the blood–brain barrier and natural filters

before the brain, but some compounds, such as the fluoride, can.

Effects

Aluminium, although rarely, can cause vitamin D-resistant osteomalacia, erythropoietin-resistant microcytic anemia, and central nervous system alterations. People with kidney insufficiency are especially at a risk.

Chronic ingestion of hydrated aluminium silicates (for excess gastric

acidity control) may result in aluminium binding to intestinal contents

and increased elimination of other metals, such as iron or zinc; sufficiently high doses (more than 50 g/day) can cause anemia. Since aluminium is excreted by kidneys, their function may be impaired by toxic amounts of aluminium.

There are five major aluminium forms absorbed by human body: the free solvated trivalent cation (Al3+(aq)); low-molecular-weight, neutral, soluble complexes (LMW-Al0(aq)); high-molecular-weight, neutral, soluble complexes (HMW-Al0(aq)); low-molecular-weight, charged, soluble complexes (LMW-Al(L)n+/−(aq)); nano and micro-particulates (Al(L)n(s)). They are transported across cell membranes or cell epi-/endothelia through five major routes: (1) paracellular; (2) transcellular; (3) active transport; (4) channels; (5) adsorptive or receptor-mediated endocytosis.

An accident in England revealed that millimolar quantities of aluminium in drinking water cause significant cognitive deficits.

Orally ingested aluminium salts can deposit in the brain. There is

research on correlation between neurological disorders, including Alzheimer's disease, and aluminium levels, but it has been inconclusive so far.

Aluminium increases estrogen-related gene expression in human breast cancer cells cultured in the laboratory. In very high doses, aluminium is associated with altered function of the blood–brain barrier. A small percentage of people have contact allergies

to aluminium and experience itchy red rashes, headache, muscle pain,

joint pain, poor memory, insomnia, depression, asthma, irritable bowel

syndrome, or other symptoms upon contact with products containing

aluminium.

Exposure to powdered aluminium or aluminium welding fumes can cause pulmonary fibrosis. Fine aluminium powder can ignite or explode, posing another workplace hazard.

Exposure routes

Food is the main source of aluminium. Drinking water contains more aluminium than solid food; however, aluminium in food may be absorbed more than aluminium from water.

Major sources of human oral exposure to aluminium include food (due to

its use in food additives, food and beverage packaging, and cooking

utensils), drinking water (due to its use in municipal water treatment),

and aluminium-containing medications (particularly antacid/antiulcer

and buffered aspirin formulations). Dietary exposure in Europeans averages to 0.2–1.5 mg/kg/week but can be as high as 2.3 mg/kg/week. Higher exposure levels of aluminium are mostly limited to miners, aluminium production workers, and dialysis patients.

Excessive consumption of antacids, antiperspirants, vaccines, and cosmetics provide significant exposure levels. Consumption of acidic foods or liquids with aluminium enhances aluminium absorption, and maltol has been shown to increase the accumulation of aluminium in nerve and bone tissues.

Treatment

In case of suspected sudden intake of a large amount of aluminium, the only treatment is deferoxamine mesylate which may be given to help eliminate aluminium from the body by chelation.

However, this should be applied with caution as this reduces not only

aluminium body levels, but also those of other metals such as copper or

iron.

Nutritionally, treatment of similar to those of other toxic metals and

includes removal of sources of aluminium from environment, enhancing

cellular energy production, enhancing activity of the eliminative

organs, and chelating aluminium with nutrients.

Environmental effects

"Bauxite tailings" storage facility in Stade, Germany. The aluminium industry generates about 70 million tons of this waste annually.

High

levels of aluminium occur near mining sites; small amounts of aluminium

are released to the environment at the coal-fired power plants or incinerators.

Aluminium in the air is washed out by the rain or normally settles down

but small particles of aluminium remain in the air for a long time.

Acidic precipitation is the main natural factor to mobilize aluminium from natural sources and the main reason for the environmental effects of aluminium;

however, the main factor of presence of aluminium in salt and

freshwater are the industrial processes that also release aluminium into

air.

In water, aluminium acts as a toxiс agent on gill-breathing animals such as fish by causing loss of plasma- and hemolymph ions leading to osmoregulatory failure.

Organic complexes of aluminium may be easily absorbed and interfere

with metabolism in mammals and birds, even though this rarely happens in

practice.

Aluminium is primary among the factors that reduce plant growth

on acidic soils. Although it is generally harmless to plant growth in

pH-neutral soils, in acid soils the concentration of toxic Al3+ cations increases and disturbs root growth and function. Wheat has developed a tolerance to aluminium, releasing organic compounds that bind to harmful aluminium cations. Sorghum is believed to have the same tolerance mechanism.

Aluminium production possesses its own challenges to the

environment on each step of the production process. The major challenge

is the greenhouse gas emissions.

These gases result from electrical consumption of the smelters and the

byproducts of processing. The most potent of these gases are perfluorocarbons from the smelting process. Released sulfur dioxide is one of the primary precursors of acid rain.

A Spanish scientific report from 2001 claimed that the fungus Geotrichum candidum consumes the aluminium in compact discs. Other reports all refer back to that report and there is no supporting original research. Better documented, the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the fungus Cladosporium resinae are commonly detected in aircraft fuel tanks that use kerosene-based fuels (not avgas), and laboratory cultures can degrade aluminium.

However, these life forms do not directly attack or consume the

aluminium; rather, the metal is corroded by microbe waste products.