The continental drift of the last 250 million years

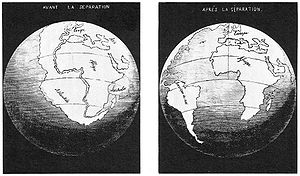

Antonio Snider-Pellegrini's Illustration of the closed and opened Atlantic Ocean (1858).

Continental drift is the theory that the Earth's continents have moved over geologic time relative to each other, thus appearing to have "drifted" across the ocean bed. The speculation that continents might have 'drifted' was first put forward by Abraham Ortelius in 1596. The concept was independently and more fully developed by Alfred Wegener in 1912, but his theory was rejected by many for lack of any motive mechanism. Arthur Holmes later proposed mantle convection for that mechanism. The idea of continental drift has since been subsumed by the theory of plate tectonics, which explains that the continents move by riding on plates of the Earth's lithosphere.

History

Early history

Abraham Ortelius (Ortelius 1596), Theodor Christoph Lilienthal (1756), Alexander von Humboldt (1801 and 1845), Antonio Snider-Pellegrini (Snider-Pellegrini 1858), and others had noted earlier that the shapes of continents on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean (most notably, Africa and South America) seem to fit together. W. J. Kious described Ortelius' thoughts in this way:

Abraham Ortelius in his work Thesaurus Geographicus ... suggested that the Americas were "torn away from Europe and Africa ... by earthquakes and floods" and went on to say: "The vestiges of the rupture reveal themselves if someone brings forward a map of the world and considers carefully the coasts of the three [continents]."

In 1889, Alfred Russel Wallace

remarked, "It was formerly a very general belief, even amongst

geologists, that the great features of the earth's surface, no less than

the smaller ones, were subject to continual mutations, and that during

the course of known geological time the continents and great oceans had,

again and again, changed places with each other." He quotes Charles Lyell

as saying, "Continents, therefore, although permanent for whole

geological epochs, shift their positions entirely in the course of

ages." and claims that the first to throw doubt on this was James Dwight Dana in 1849.

In his Manual of Geology (1863), Dana wrote, "The

continents and oceans had their general outline or form defined in

earliest time. This has been proved with respect to North America from

the position and distribution of the first beds of the Silurian – those

of the Potsdam epoch. … and this will probably prove to the case in

Primordial time with the other continents also". Dana was enormously influential in America – his Manual of Mineralogy is still in print in revised form – and the theory became known as Permanence theory.

This appeared to be confirmed by the exploration of the deep sea beds conducted by the Challenger expedition,

1872-6, which showed that contrary to expectation, land debris brought

down by rivers to the ocean is deposited comparatively close to the

shore on what is now known as the continental shelf. This suggested that the oceans were a permanent feature of the Earth's surface, and did not change places with the continents.

Wegener and his predecessors

Alfred Wegener

Apart from the earlier speculations mentioned in the previous

section, the idea that the American continents had once formed a single

landmass together with Europe and Asia before assuming their present

shapes and positions was speculated by several scientists before Alfred Wegener's 1912 paper.

Although Wegener's theory was formed independently and was more complete

than those of his predecessors, Wegener later credited a number of past

authors with similar ideas:

Franklin Coxworthy (between 1848 and 1890), Roberto Mantovani (between 1889 and 1909), William Henry Pickering (1907) and Frank Bursley Taylor (1908). In addition, Eduard Suess had proposed a supercontinent Gondwana in 1885 and the Tethys Ocean in 1893, assuming a land-bridge between the present continents submerged in the form of a geosyncline, and John Perry had written an 1895 paper proposing that the earth's interior was fluid, and disagreeing with Lord Kelvin on the age of the earth.

For example: the similarity of southern continent geological formations had led Roberto Mantovani to conjecture in 1889 and 1909 that all the continents had once been joined into a supercontinent;

Wegener noted the similarity of Mantovani's and his own maps of the

former positions of the southern continents. In Mantovani's conjecture,

this continent broke due to volcanic activity caused by thermal expansion,

and the new continents drifted away from each other because of further

expansion of the rip-zones, where the oceans now lie. This led Mantovani

to propose an Expanding Earth theory which has since been shown to be incorrect.

Continental drift without expansion was proposed by Frank Bursley Taylor,

who suggested in 1908 (published in 1910) that the continents were

moved into their present positions by a process of "continental creep".

In a later paper he proposed that this occurred by their being dragged

towards the equator by tidal forces during the hypothesized capture of

the moon in the Cretaceous,

resulting in "general crustal creep" toward the equator. Although his

proposed mechanism was wrong, he was the first to realize the insight

that one of the effects of continental motion would be the formation of

mountains, and attributed the formation of the Himalayas to the

collision between the Indian subcontinent with Asia.

Wegener said that of all those theories, Taylor's, although not fully

developed, had the most similarities to his own. In the mid-20th

century, the theory of continental drift was referred to as the

"Taylor-Wegener hypothesis", although this terminology eventually fell out of common use.

Alfred Wegener first presented his hypothesis to the German Geological Society on 6 January 1912. His hypothesis was that the continents had once formed a single landmass, called Pangaea, before breaking apart and drifting to their present locations.

Wegener was the first to use the phrase "continental drift" (1912, 1915)

(in German "die Verschiebung der Kontinente" – translated into English

in 1922) and formally publish the hypothesis that the continents had

somehow "drifted" apart. Although he presented much evidence for

continental drift, he was unable to provide a convincing explanation for

the physical processes which might have caused this drift. His

suggestion that the continents had been pulled apart by the centrifugal pseudoforce (Polflucht) of the Earth's rotation or by a small component of astronomical precession was rejected, as calculations showed that the force was not sufficient. The Polflucht hypothesis was also studied by Paul Sophus Epstein in 1920 and found to be implausible.

Rejection of Wegener's theory, 1910s–1950s

The theory of continental drift was not accepted for many years. One problem was that a plausible driving force was missing. A second problem was that Wegener's estimate of the velocity of continental motion, 250 cm/year, was implausibly high. (The currently accepted rate for the separation of the Americas from Europe and Africa is about 2.5 cm/year).

It also did not help that Wegener was not a geologist. Other

geologists also believed that the evidence that Wegener had provided was

not sufficient. It is now accepted that the plates carrying the

continents do move across the Earth's surface, although not as fast as

Wegener believed; ironically one of the chief outstanding questions is

the one Wegener failed to resolve: what is the nature of the forces

propelling the plates?

The British geologist Arthur Holmes

championed the theory of continental drift at a time when it was deeply

unfashionable. He proposed in 1931 that the Earth's mantle contained

convection cells which dissipated radioactive heat and moved the crust

at the surface. His Principles of Physical Geology, ending with a chapter on continental drift, was published in 1944.

Geological maps of the time showed huge land bridges spanning the

Atlantic and Indian oceans to account for the similarities of fauna and

flora and the divisions of the Asian continent in the Permian era but

failing to account for glaciation in India, Australia and South Africa.

Geophysicist Jack Oliver

is credited with providing seismologic evidence supporting plate

tectonics which encompassed and superseded continental drift with the

article "Seismology and the New Global Tectonics", published in 1968,

using data collected from seismologic stations, including those he set

up in the South Pacific.

It is now known that there are two kinds of crust: continental crust and oceanic crust.

Continental crust is inherently lighter and its composition is

different from oceanic crust, but both kinds reside above a much deeper "plastic" mantle. Oceanic crust is created at spreading centers, and this, along with subduction, drives the system of plates in a chaotic manner, resulting in continuous orogeny and areas of isostatic imbalance. The theory of plate tectonics explains all this, including the movement of the continents, better than Wegener's theory.

The fixists

Hans Stille and Leopold Kober opposed the idea of continental drift and worked on a "fixist" geosyncline model with Earth contraction playing a key role in the formation of orogens. Other geologists who opposed continental drift were Bailey Willis, Charles Schuchert, Rollin Chamberlin and Walther Bucher. In 1939 an international geological conference was held in Frankfurt.

This conference came to be dominated by the fixists, especially as

those geologists specializing in tectonics were all fixists except

Willem van der Gracht.

Criticism of continental drift and mobilism was abundant at the

conference not only from tectonicists but also from sedimentological

(Nölke), paleontological (Nölke), mechanical (Lehmann) and oceanographic

(Troll, Wüst) perspectives. Hans Cloos, the organizer of the conference, was also a fixist who together with Troll held the view that excepting the Pacific Ocean continents were not radically different from oceans in their behaviour. The mobilist theory of Émile Argand for the Alpine orogeny was criticized by Kurt Leuchs. The few drifters and mobilists at the conference appealed to biogeography (Kirsch, Wittmann), paleoclimatology (Wegener, K), paleontology (Gerth) and geodetic measurements (Wegener, K). F. Bernauer correctly equated Reykjanes in south-west Iceland with the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, arguing with this that the floor of the Atlantic Ocean was undergoing extension

just like Reykjanes. Bernauer thought this extension had drifted the

continents only 100–200 km apart, the approximate width of the volcanic zone in Iceland.

David Attenborough,

who attended university in the second half of the 1940s, recounted an

incident illustrating its lack of acceptance then: "I once asked one of

my lecturers why he was not talking to us about continental drift and I

was told, sneeringly, that if I could prove there was a force that could

move continents, then he might think about it. The idea was moonshine, I

was informed."

As late as 1953 – just five years before Carey introduced the theory of plate tectonics – the theory of continental drift was rejected by the physicist Scheidegger on the following grounds.

- First, it had been shown that floating masses on a rotating geoid would collect at the equator, and stay there. This would explain one, but only one, mountain building episode between any pair of continents; it failed to account for earlier orogenic episodes.

- Second, masses floating freely in a fluid substratum, like icebergs in the ocean, should be in isostatic equilibrium (in which the forces of gravity and buoyancy are in balance). But gravitational measurements showed that many areas are not in isostatic equilibrium.

- Third, there was the problem of why some parts of the Earth's surface (crust) should have solidified while other parts were still fluid. Various attempts to explain this foundered on other difficulties.

Road to acceptance

From the 1930s to the late 1950s, works by Vening-Meinesz, Holmes, Umbgrove,

and numerous others outlined concepts that were close or nearly

identical to modern plate tectonics theory. In particular, the English

geologist Arthur Holmes proposed in 1920 that plate junctions might lie

beneath the sea, and in 1928 that convection currents within the mantle might be the driving force. Holmes' views were particularly influential: in his bestselling textbook, Principles of Physical Geology, he included a chapter on continental drift, proposing that Earth's mantle contained convection cells which dissipated radioactive heat and moved the crust at the surface.

Holmes' proposal resolved the phase disequilibrium objection (the

underlying fluid was kept from solidifying by radioactive heating from

the core). However, scientific communication in the '30 and '40s was

inhibited by the war, and the theory still required work to avoid foundering on the orogeny and isostasy

objections. Worse, the most viable forms of the theory predicted the

existence of convection cell boundaries reaching deep into the earth

that had yet to be observed.

In 1947, a team of scientists led by Maurice Ewing

confirmed the existence of a rise in the central Atlantic Ocean, and

found that the floor of the seabed beneath the sediments was chemically

and physically different from continental crust.

As oceanographers continued to bathymeter the ocean basins, a system

of mid-oceanic ridges was detected. An important conclusion was that

along this system, new ocean floor was being created, which led to the

concept of the "Great Global Rift".

Meanwhile, scientists began recognizing odd magnetic variations

across the ocean floor using devices developed during World War II to

detect submarines.

Over the next decade, it became increasingly clear that the

magnetization patterns were not anomalies, as had been originally

supposed. In a series of papers in 1959-1963, Heezen, Dietz, Hess,

Mason, Vine, Matthews, and Morley collectively realized that the

magnetization of the ocean floor formed extensive, zebra-like patterns:

one stripe would exhibit normal polarity and the adjoining stripes

reversed polarity. The best explanation was the "conveyor belt" or Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis. New magma

from deep within the Earth rises easily through these weak zones and

eventually erupts along the crest of the ridges to create new oceanic

crust. The new crust is magnetized by the earth's magnetic field, which

undergoes occasional reversals. Formation of new crust then displaces the magnetized crust apart, akin to a conveyor belt — hence the name.

Without workable alternatives to explain the stripes,

geophysicists were forced to conclude that Holmes had been right: ocean

rifts were sites of perpetual orogeny at the boundaries of convection

cells.

By 1967, barely two decades after discovery of the mid-oceanic rifts,

and a decade after discovery of the striping, plate tectonics had become

axiomatic to modern geophysics.

In addition, Marie Tharp, in collaboration with Bruce Heezen, who

initially ridiculed Tharp's observations that her maps confirmed

continental drift theory, provided essential corroboration, using her

skills in cartography and seismographic data, to confirm the theory.

Modern evidence

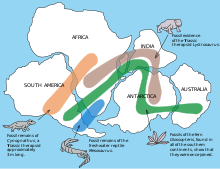

Fossil patterns across continents (Gondwanaland).

Mesosaurus skeleton, MacGregor, 1908.

Evidence for the movement of continents on tectonic plates is now extensive. Similar plant and animal fossils are found around the shores of different continents, suggesting that they were once joined. The fossils of Mesosaurus, a freshwater reptile rather like a small crocodile, found both in Brazil and South Africa, are one example; another is the discovery of fossils of the land reptile Lystrosaurus in rocks of the same age at locations in Africa, India, and Antarctica. There is also living evidence, with the same animals being found on two continents. Some earthworm families (such as Ocnerodrilidae, Acanthodrilidae, Octochaetidae) are found in South America and Africa.

The complementary arrangement of the facing sides of South

America and Africa is obvious but a temporary coincidence. In millions

of years, slab pull, ridge-push, and other forces of tectonophysics

will further separate and rotate those two continents. It was that

temporary feature that inspired Wegener to study what he defined as

continental drift although he did not live to see his hypothesis

generally accepted.

The widespread distribution of Permo-Carboniferous

glacial sediments in South America, Africa, Madagascar, Arabia, India,

Antarctica and Australia was one of the major pieces of evidence for the

theory of continental drift. The continuity of glaciers, inferred from

oriented glacial striations and deposits called tillites, suggested the existence of the supercontinent of Gondwana,

which became a central element of the concept of continental drift.

Striations indicated glacial flow away from the equator and toward the

poles, based on continents' current positions and orientations, and

supported the idea that the southern continents had previously been in

dramatically different locations that were contiguous with one another.