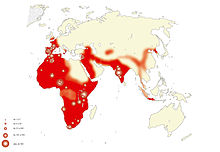

Successive dispersals of Homo erectus (yellow), Homo neanderthalensis (ochre) and Homo sapiens (red).

Several expansions of populations of archaic humans (genus Homo) out of Africa and throughout Eurasia took place in the course of the Lower Paleolithic, and into the beginning Middle Paleolithic, between about 2.1 million and 0.2 million years ago (Ma).

These expansions are collectively known as Out of Africa I, in contrast to the expansion of Homo sapiens

(anatomically modern humans) into Eurasia, which may have begun shortly after 0.2 million years ago (known in this context as "Out of Africa II").

The earliest presence of Homo (or indeed any hominin) outside of Africa dates to close to 2 million years ago.

A 2018 study claims human presence at Shangchen, central China, as early as 2.12 Ma based on

magnetostratigraphic dating of the lowest layer containing stone artefacts.[2]

The oldest known human skeletal remains outside of Africa are from Dmanisi, Georgia (Dmanisi skull 4), and are dated to 1.8 Ma. These remains are classified as Homo erectus georgicus.

Later waves of expansion are proposed around 1.4 Ma (early Acheulean industries), associated with Homo antecessor and 0.8 Ma (cleaver-producing Acheulean groups, associated with Homo heidelbergensis).

Until the early 1980s, early humans were thought to have been restricted to the African continent in the Early Pleistocene,

or until about 0.8 Ma; Hominin migrations outside East Africa were

apparently rare in the Early Pleistocene, leaving a fragmentary record

of events.

Early dispersals

Forensic interpretation of Homo habilis

Pre-Homo hominin expansion out of Africa is suggested by the presence of Graecopithecus and Ouranopithecus, found in Greece and Anatolia and dated to c. 8 million years ago, but these are probably Homininae but not Hominini. Possibly related are the Trachilos footprints found in Crete, dated to close to 6 million years ago.

Australopithecina emerge about 5.6 million years ago, in East Africa (Afar Depression).

Gracile australopithecines (Australopithecus afarensis) emerge in the same region, around 4 million years ago.

The earliest known retouched tools were found in Lomekwi, Kenya, and date back to 3.3 Ma, in the late Pliocene. They might be the product of Australopithecus garhi or Paranthropus aethiopicus, the two known hominins contemporary with the tools.

Homo is assumed to have emerged by around 2 million years ago, Homo habilis being

found at about 2.1 million years ago at Lake Turkana, Kenya. The delineation of the "human" genus, Homo,

from Australopithecus is somewhat contentious, for which reason the

superordinate term "hominin" is often used to include both.

"Hominin" technically includes chimpanzees as well as pre-human species as old as 10 million years ago (the separation of Homininae into Hominini and Gorillini).

The earliest known hominin presence outside of Africa, dates to

close to 2 million years ago. A 2018 study claims evidence for human

presence at Shangchen, central China, as early as 2.12 Ma based on magnetostratigraphic dating of the lowest layer containing stone artefacts.

It has been suggested that Homo floresiensis

was descended from such an early expansion. It is not clear whether

these earliest hominins leaving Africa should be considered

Homo habilis, or a form of early Homo or late Australopithecus closely related to Homo habilis, or a very early form of Homo erectus.

In any case, the morphology of H. floresiensis has been found to show greatest similarity with Australopithecus sediba, Homo habilis and Dmanisi Man, raising the possibility that the ancestors of H. floresiensis left Africa before the appearance of H. erectus.

A phylogenetic analysis published in 2017 suggests that H. floresiensis was descended from a species (presumably Australopithecine) ancestral to Homo habilis, making it a "sister species" either to H. habilis or to a minimally habilis-erectus-ergaster-sapiens clade, and its line is older than H. erectus itself. On the basis of this classification, H. floresiensis

is hypothesized to represent a hitherto unknown and very early

migration out of Africa, dating to before 2.1 million years ago. A

similar conclusion is suggested by the date of 2.1 Ma for the oldest Shangchen artefacts.

Homo erectus

Forensic reconstruction of an adult male Homo erectus.

Homo erectus emerges just after 2 million years ago.

Early H. erectus would have lived face to face with H. habilis in East Africa for nearly half a million years.

The oldest Homo erectus fossils appear almost contemporaneously, shortly after two million years ago, both in Africa and in the Caucasus.

The earliest well-dated Eurasian H. erectus site is Dmanisi in Georgia, securely dated to 1.8 Ma. A skull found at Dmanisi is evidence for caring for the old. The skull shows that this Homo erectus

was advanced in age and had lost all but one tooth years before death,

and it is perhaps unlikely that this hominid would have survived alone.

It is not certain, however, that this is sufficient proof for caring – a

partially paralysed chimpanzee at the Gombe reserve survived for years

without help.

The earliest known evidence for African H. erectus, dubbed Homo ergaster, is a

single occipital bone (KNM-ER 2598), described as "H. erectus-like", and dated to about 1.9 Ma (contemporary with Homo rudolfensis). This is followed by a fossil gap, the next available fossil being KNM-ER 3733, a skull dated to 1.6 Ma.

Early Pleistocene

sites in North Africa, the geographical intermediate of East Africa and

Georgia, are in poor stratigraphic context. The earliest of the dated

is Ain Hanech in northern Algeria (c. 1.8 – 1.2 Ma), an Oldowan grade layer. These sites attest that early Homo erectus have crossed the North African tracts, which are usually hot and dry.

There is little time between Homo erectus’ apparent arrival in South Caucasus around 1.8 Ma, and its probable arrival in East and Southeast Asia. There is evidence of H. erectus in Yuanmou, China, dating to 1.7 Ma and in Sangiran, on Java, Indonesia, from 1.66 Ma.

Ferring et al. (2011) suggest that it was still Homo habilis that reached West Asia, and that early H. erectus developed there. H. erectus would then have dispersed from West Asia, to East Asia (Peking Man) Southeast Asia (Java Man), back to Africa (Homo ergaster), and to Europe (Tautavel Man).

It appears H. erectus took longer to move into Europe, the earliest site being Barranco León in southeastern Spain dated to 1.4 Ma, associated with Homo antecessor. and a controversial Pirro Nord in Southern Italy, allegedly from 1.7 – 1.3 Ma. The paleobiogeography of early human dispersals in western Eurasia characterizes H. ex gr. erectus as a temperature sensitive stenobiont, that failed to disperse north of the Alpide Belt . The geographically restricted earliest human presence in the Iberian Peninsula should be regarded as an evidence of sustainable presence of human population in this isolated area. The Pannonian plane situated south-west from the Carpathian Mountains

apparently was characterized by comparatively warm climate similar to

that of the Mediterranean Area, while the climate of the western

European paleobiogeographic area was mitigated by Gulf Stream influence and could support the episodic hominin dispersals toward the Iberian Peninsula. Apparently, the faunal exchanges between southeastern Europe and the

Near East and southern Asia were controlled by the complex interaction

of such geographic obstacles as the Bosporus and the Manych Strait, the climate barrier from the north of the Greater Caucasus range, and the 41 kyr glacial Milankovitch cycles that repeatedly closed Bosporus and thus triggered the two-way faunal exchange between southeastern Europe and Near East, and, apparently, the further westward dispersal of the archaic hominins in Eurasia.

By 1 Ma, Homo erectus had spread across Eurasia (mostly restricted to latitudes south of the 50th parallel north).

It is hard to say, however, whether settlement was continuous in Western

Europe, or if successive waves repopulated the territory in glacial

interludes. Early Acheulean tools at Ubeidiya from 1.4 Ma

is some evidence for a continuous settlement in the West, as successive

waves out of Africa after then would likely have brought Acheulean

technology to Western Europe.

Presence of Lower Paleolithic human remains in Indonesian islands is good evidence for seafaring by Homo erectus

late in the Early Pleistocene. Bednarik suggests that navigation had

appeared by 1 Ma, possibly to exploit offshore fishing grounds. He has reproduced a primitive dirigible raft to demonstrate the feasibility of faring across the Lombok Strait

on such a device, which he believes to have been done before 850 ka.

The strait has maintained a width of at least 20 km for the whole of the

Pleistocene. Such an achievement by Homo erectus in the Early Pleistocene offers some strength to the suggested water routes out of Africa, as the Gibraltar, Sicilian, and Bab-el-Mandeb exit routes are harder to consider if watercraft are deemed beyond the capacities of Homo erectus.

Homo heidelbergensis

Forensic interpretation of an adult male Homo rhodesiensis based on the Kabwe skull.

Archaic humans in Europe beginning about 0.8 Ma (cleaver-producing Acheulean groups)

are classified as a separate, erectus-derived species, known as Homo heidelbergensis. H. heidelbergensis from about 0.4 Ma develops its own characteristic industry, known as Clactonian.

H. heidelbergensis is closely related to Homo rhodesiensis (also identified as Homo heidelbergensis sensu lato or African H. heidelbergensis), known to be present in southern Africa by 0.3 Ma.

Homo sapiens emerges before about 0.3 Ma from a lineage closely related to early H. heidelbergensis. The earliest presence of H. sapiens in West Asia, and thus the beginning of "Out of Africa II", may date to as early as 0.3 Ma and is ascertained for 0.13 Ma.

Routes out of Africa

Most attention as to the route taken from Africa to West Asia is given to the Bab-el-Mandeb,

connecting the Horn of Africa and Arabia, which may have allowed dry

passage during some periods of the Pleistocene. Other candidates are Levantine corridor and the Strait of Gibraltar. A route across the Strait of Sicily was suggesed in the 1970s but is not now considered likely.

Bab-el-Mandeb strait

Bab-el-Mandeb is a 30 km strait between East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, with a small island, Perim,

3 km off the Arabian bank. The strait has a major appeal in the study

of Eurasian expansion in that it brings East Africa in direct proximity

with Eurasia. It does not require hopping from one water body to the

next across the North African desert.

The land connection with Arabia disappeared in the Pliocene, and though it may have briefly reformed,

the evaporation of the Red Sea and associated increase in salinity

would have left traces in the fossil record after just 200 years and evaporite deposits after 600 years. Neither have been detected. A strong current flows from the Red Sea into the Indian Ocean and crossing would have been difficult without a land connection.

Oldowan grade tools are reported from Perim Island, implying that the strait could have been crossed in the Early Pleistocene, but these finds have yet to be confirmed.

The Strait of Gibraltar is the Atlantic entryway to the Mediterranean, where Spanish and Moroccan banks are only 14 km apart. A decrease in sea levels in the Pleistocene due to glaciation

would not have brought this down to less than 10 km. Deep currents

push westwards, and surface water flows strongly back into the

Mediterranean.

Entrance into Eurasia across the strait of Gibraltar could explain the

hominin remains at Barranco León in southeastern Spain (1.4 Ma) and Sima del Elefante in northern Spain (1.2 Ma). But the site of Pirro Nord in southern Italy, allegedly from 1.3 – 1.7 Ma, suggests a possible arrival from the East. Resolution is insufficient to settle the matter.

Passage across the Strait of Sicily was suggested by Alimen (1975) based on the 1973 discovery Sicilian Oldowan grade tools in Sicily.

Radiometric dates, however, have not been produced, and the artefacts might as well be from the Middle Pleistocene,

and it is unlikely that there was a land bridge during the Pleistocene.

Causes for dispersal

Climate change and hominin flexibility

For

a given species in a given environment, available resources will limit

the number of individuals that can survive indefinitely.

This is the carrying capacity.

Upon reaching this threshold, individuals may find it easier to gather

resources in the poorer yet less exploited peripheral environment than

in the preferred habitat. Homo habilis could have developed some

baseline behavioural flexibility prior to its expansion into the

peripheries (such as encroaching into the predatory guild). This flexibility could then have been positively selected and amplified, leading to Homo erectus' adaptation to the peripheral open habitats.

A new and environmentally flexible hominin population could have come

back to the old niche and replaced the ancestral population.

Moreover, some step-wise shrinking of the woodland and the associated

reduction of hominin carrying capacity in the woods around 1.8 Ma, 1.2

Ma, and 0.6 Ma would have stressed the carrying capacity's pressure for

adapting to the open grounds.

With Homo erectus'

new environmental flexibility, favourable climate fluxes likely opened

it the way to the Levantine corridor, perhaps sporadically, in the Early

Pleistocene.

Chasing fauna

Lithic analysis implies that Oldowan hominins were not predators. However, Homo erectus

appears to have followed animal migrations to the north during wetter

periods, likely as a source of scavenged food. The sabre-tooth cat

Megantereon was an apex predator of the Early and Middle Pleistocene

(before MIS 12). It became extinct in Africa c. 1.5 Ma, but had already moved out through the Sinai, and is among the faunal remains of the Levantine hominin site of Ubeidiya, c. 1.4 Ma. It could not break bone marrow and its kills were likely an important food source for hominins, especially in glacial periods.

In colder Eurasian times, the hominin diet would have to be

principally meat-based and Acheulean hunters must have competed with

cats.

Coevolved zoonotic diseases

Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen suggest that the success of hominins within Eurasia once out of Africa is in part due to the absence of zoonotic diseases

outside their original habitat. Zoonotic diseases are those that are

transmitted from animals to humans. While a disease specific to hominins

must keep its human host alive long enough to transmit itself, zoonotic

diseases will not necessarily do so as they can complete their life

cycle without humans. Still, these infections are well accustomed to

human presence, having evolved alongside them. The higher an African

ape's population density, the better a disease fares. 55% of chimps at

the Gombe reserve die of disease, most of them zoonotic.

The majority of these diseases are still restricted to hot and damp

African environments. Once hominins had moved out into drier and colder

habitats of higher latitudes, one major limiting factor in population

growth was out of the equation.

Physiological traits

While Homo habilis was certainly bipedal, its long arms are indicative of an arboreal adaptation. Homo erectus

had longer legs and shorter arms, revealing a transition to obligate

terrestriality, though it remains unclear how this change in relative

leg length might have been an advantage. Sheer body size, on the other hand, seems to have allowed for better walking energy efficiency and endurance. A larger Homo erectus would also dehydrate more slowly and could thus cover greater distances before facing thermoregulatory limitations. The ability for prolonged walking at a normal pace would have been a decisive factor for effective colonisation of Eurasia.