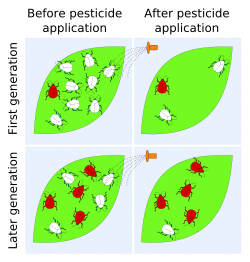

Pesticide

application can artificially select for resistant pests. In this

diagram, the first generation happens to have an insect with a

heightened resistance to a pesticide (red). After pesticide application,

its descendants represent a larger proportion of the population,

because sensitive pests (white) have been selectively killed. After

repeated applications, resistant pests may comprise the majority of the

population.

Pesticide resistance describes the decreased susceptibility of a pest population to a pesticide that was previously effective at controlling the pest. Pest species evolve pesticide resistance via natural selection: the most resistant specimens survive and pass on their acquired heritable changes traits to their offspring.

Cases of resistance have been reported in all classes of pests (i.e. crop diseases, weeds, rodents, etc.), with 'crises' in insect control occurring early-on after the introduction of pesticide use in the 20th century. The Insecticide Resistance Action Committee (IRAC) definition of insecticide resistance is 'a heritable

change in the sensitivity of a pest population that is reflected in the

repeated failure of a product to achieve the expected level of control

when used according to the label recommendation for that pest species'.

Pesticide resistance is increasing. Farmers in the US

lost 7% of their crops to pests in the 1940s; over the 1980s and 1990s,

the loss was 13%, even though more pesticides were being used. Over 500 species of pests have evolved a resistance to a pesticide. Other sources estimate the number to be around 1,000 species since 1945.

Although the evolution of pesticide resistance is usually

discussed as a result of pesticide use, it is important to keep in mind

that pest populations can also adapt to non-chemical methods of control.

For example, the northern corn rootworm (Diabrotica barberi) became adapted to a corn-soybean crop rotation by spending the year when field is planted to soybeans in a diapause.

As of 2014, few new weed killers are near commercialization, and none with a novel, resistance-free mode of action.

Causes

Pesticide resistance probably stems from multiple factors:

Many pest species produce large broods. This increases the

probability of mutations and ensures the rapid expansion of resistant

populations.

Pest species had been exposed to natural toxins long before agriculture began. For example, many plants produce phytotoxins

to protect them from herbivores. As a result, coevolution of herbivores

and their host plants required development of the physiological

capability to detoxify or tolerate poisons.

Humans often rely almost exclusively on pesticides for pest

control. This increases selection pressure towards resistance.

Pesticides that fail to break down quickly contribute to selection for

resistant strains even after they are no longer being applied.

In response to resistance, managers may increase pesticide

quantities/frequency, which exacerbates the problem. In addition, some

pesticides are toxic toward species that feed on or compete with pests.

This can allow the pest population to expand, requiring more pesticides.

This is sometimes referred to as pesticide trap, or a pesticide treadmill, since farmers progressively pay more for less benefit.

Insect predators and parasites generally have smaller populations

and are less likely to evolve resistance than are pesticides' primary

targets, such as mosquitoes and those that feed on plants. Weakening

them allows the pests to flourish. Alternatively, resistant predators can be bred in laboratories.

Pests with limited diets are more likely to evolve resistance,

because they are exposed to higher pesticide concentrations and has less

opportunity to breed with unexposed populations.

Pests with shorter generation times develop resistance more quickly than others.

Examples

Resistance has evolved in multiple species: resistance to insecticides

was first documented by A. L. Melander in 1914 when scale insects

demonstrated resistance to an inorganic insecticide. Between 1914 and

1946, 11 additional cases were recorded. The development of organic

insecticides, such as DDT, gave hope that insecticide resistance was a dead issue. However, by 1947 housefly resistance to DDT had evolved. With the introduction of every new insecticide class – cyclodienes, carbamates, formamidines, organophosphates, pyrethroids, even Bacillus thuringiensis – cases of resistance surfaced within two to 20 years.

- Studies in America have shown that fruit flies that infest orange groves were becoming resistant to malathion.

- In Hawaii, Japan and Tennessee, the diamondback moth evolved a resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis about three years after it began to be used heavily.

- In England, rats in certain areas have evolved resistance that allows them to consume up to five times as much rat poison as normal rats without dying.

- DDT is no longer effective in preventing malaria in some places.

- In the southern United States, Amaranthus palmeri, which interferes with cotton production, has evolved resistance to the herbicide glyphosate.

- The Colorado potato beetle has evolved resistance to 52 different compounds belonging to all major insecticide classes. Resistance levels vary across populations and between beetle life stages, but in some cases can be very high (up to 2,000-fold).

- The cabbage looper is an agricultural pest that is becoming increasingly problematic due to its increasing resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis, as demonstrated in Canadian greenhouses. Further research found a genetic component to Bt resistance.

Multiple and cross-resistance

- Multiple-resistance pests are resistant to more than one class of pesticide. This can happen when pesticides are used in sequence, with a new class replacing one to which pests display resistance with another.

- Cross-resistance, a related phenomenon, occurs when the genetic mutation that made the pest resistant to one pesticide also makes it resistant to others, often those with a similar mechanism of action.

Adaptation

Pests becomes resistant by evolving physiological changes that protect them from the chemical.

One protection mechanism is to increase the number of copies of a gene, allowing the organism to produce more of a protective enzyme that breaks the pesticide into less toxic chemicals. Such enzymes include esterases, glutathione transferases, and mixed microsomal oxidases.

Alternatively, the number and/or sensitivity of biochemical receptors that bind to the pesticide may be reduced.

Behavioral resistance has been described for some chemicals. For example, some Anopheles mosquitoes evolved a preference for resting outside that kept them away from pesticide sprayed on interior walls.

Resistance may involve rapid excretion of toxins, secretion of

them within the body away from vulnerable tissues and decreased

penetration through the body wall.

Mutation in only a single gene can lead to the evolution of a

resistant organism. In other cases, multiple genes are involved.

Resistant genes are usually autosomal. This means that they are located

on autosomes (as opposed to allosomes,

also known as sex chromosomes). As a result, resistance is inherited

similarly in males and females. Also, resistance is usually inherited as

an incompletely dominant trait. When a resistant individual mates with a

susceptible individual, their progeny generally has a level of

resistance intermediate between the parents.

Adaptation to pesticides comes with an evolutionary cost, usually

decreasing relative fitness of organisms in the absence of pesticides.

Resistant individuals often have reduced reproductive output, life

expectancy, mobility, etc. Non-resistant individuals grow in frequency

in the absence of pesticides, offering one way to combat resistance.

Blowfly maggots produce an enzyme that confers resistance to organochloride

insecticides. Scientists have researched ways to use this enzyme to

break down pesticides in the environment, which would detoxify them and

prevent harmful environmental effects. A similar enzyme produced by soil

bacteria that also breaks down organochlorides works faster and remains

stable in a variety of conditions.

Management

Integrated pest management (IPM) approach provides a balanced approach to minimizing resistance.

Resistance can be managed by reducing use of a pesticide. This

allows non-resistant organisms to out-compete resistant strains. They

can later be killed by returning to use of the pesticide.

A complementary approach is to site untreated refuges near treated croplands where susceptible pests can survive.

When pesticides are the sole or predominant method of pest

control, resistance is commonly managed through pesticide rotation. This

involves switching among pesticide classes with different modes of

action to delay or mitigate pest resistance. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) designates different classes of fungicides, herbicides

and insecticides. Manufacturers may recommend no more than a specified

number of consecutive applications of a pesticide class be made before

moving to a different pesticide class.

Two or more pesticides with different modes of action can be

tankmixed on the farm to improve results and delay or mitigate existing

pest resistance.

Status

Glyphosate

Glyphosate-resistant weeds are now present in the vast majority of soybean, cotton, and corn farms in some U.S. states. Weeds resistant to multiple herbicide modes of action are also on the rise.

Before glyphosate, most herbicides would kill a limited number of weed species, forcing farmers to continually rotate their crops

and herbicides to prevent resistance. Glyphosate disrupts the ability

of most plants to construct new proteins. Glyphosate-tolerant transgenic crops are not affected.

A weed family that includes waterhemp (Amaranthus rudis)

has developed glyphosate-resistant strains. A 2008 to 2009 survey of

144 populations of waterhemp in 41 Missouri counties revealed glyphosate

resistance in 69%. Weed surveys from some 500 sites throughout Iowa in

2011 and 2012 revealed glyphosate resistance in approximately 64% of

waterhemp samples.

In response to the rise in glyphosate resistance, farmers turned

to other herbicides—applying several in a single season. In the United

States, most midwestern and southern farmers continue to use glyphosate

because it still controls most weed species, applying other herbicides,

known as residuals, to deal with resistance.

The use of multiple herbicides appears to have slowed the spread

of glyphosate resistance. From 2005 through 2010 researchers discovered

13 different weed species that had developed resistance to glyphosate.

From 2010-2014 only two more were discovered.

A 2013 Missouri survey showed that multiply-resistant weeds had

spread. 43% of the sampled weed populations were resistant to two

different herbicides, 6% to three and 0.5% to four. In Iowa a survey

revealed dual resistance in 89% of waterhemp populations, 25% resistant

to three and 10% resistant to five.

Resistance increases pesticide costs. For southern cotton,

herbicide costs climbed from between $50 and $75 per hectare a few years

ago to about $370 per hectare in 2014. In the South, resistance

contributed to the shift that reduced cotton planting by 70% in Arkansas

and 60% in Tennessee. For soybeans in Illinois, costs rose from about

$25 to $160 per hectare.

B. thuringiensis

During 2009 and 2010, some Iowa fields showed severe injury to corn producing Bt toxin Cry3Bb1 by western corn rootworm. During 2011, mCry3A corn also displayed insect damage, including cross-resistance

between these toxins. Resistance persisted and spread in Iowa. Bt corn

that targets western corn rootworm does not produce a high dose of Bt

toxin, and displays less resistance than that seen in a high-dose Bt

crop.

Products such as Capture LFR (containing the pyrethroid Bifenthrin) and SmartChoice (containing a pyrethroid and an organophosphate)

have been increasingly used to complement Bt crops that farmers find

alone to be unable to prevent insect-driven injury. Multiple studies

have found the practice to be either ineffective or to accelerate the

development of resistant strains.