| Bison | |

|---|---|

| |

| American bison (Bison bison) | |

| |

| European bison (Bison bonasus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Bovinae |

| Subtribe: | Bovina |

| Genus: | Bison Hamilton Smith, 1827 |

| Species | |

Bison are large, even-toed ungulates in the genus Bison within the subfamily Bovinae.

Two extant and six extinct species are recognised. Of the six extinct species, five became extinct in the Quaternary extinction event. Bison palaeosinensis evolved in the Early Pleistocene in South Asia, and was the evolutionary ancestor of B. priscus (steppe bison), which was the ancestor of all other Bison species. From 2 MYA to 6,000 BC, steppe bison ranged across the mammoth steppe, inhabiting Europe and northern Asia with B. schoetensacki (woodland bison), and North America with B. antiquus, B. latifrons, and B. occidentalis. The last species to go extinct, B. occidentalis, was succeeded at 3,000 BC by B. bison.

Of the two surviving species, the American bison, B. bison, found only in North America, is the more numerous. Although commonly known as a buffalo in the United States and Canada, it is only distantly related to the true buffalo. The North American species is composed of two subspecies, the Plains bison, B. b. bison, and the Wood bison, B. b. athabascae, which is the namesake of Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada. A third subspecies, the Eastern Bison (B. b. pennsylvanicus) is no longer considered a valid taxon, being a junior synonym of B. b. bison. References to "Woods Bison" or "Wood Bison" from the eastern United States confusingly refer to this subspecies, not B. b. athabascae, which was not found in the region. The European bison, B. bonasus, or wisent, is found in Europe and the Caucasus, reintroduced after being extinct in the wild.

While all bison species are classified in their own genus, they are sometimes bred with domestic cattle (genus Bos) and produce fertile offspring called beefalo or zubron.

Description

Magdalenian bison on plaque, 17,000–9,000 BC, Bédeilhac grottoe, Ariège

The American bison and the European bison (wisent) are the largest

surviving terrestrial animals in North America and Europe. They are

typical artiodactyl

(cloven hooved) ungulates, and are similar in appearance to other

bovines such as cattle and true buffalo. They are broad and muscular

with shaggy coats of long hair. Adults grow up to 1.8 metres (5 ft

11 in) in length for American Bison and up to 2.8 metres (9 ft 2 in) in length for European bison. American bison can weigh from approximately 400 kilograms (880 lb) to 900 kg (2,000 lb) and European bison can weight from 800 kilograms (1,800 lb) to 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb). European bison tend to be taller and heavier than American bison.

Bison are nomadic grazers and travel in herds.

The bulls leave the herds of females at two or three years of age, and

join a male herd, which are generally smaller than female herds. Mature

bulls rarely travel alone. Towards the end of the summer, for the

reproductive season, the sexes necessarily commingle.

American bison are known for living in the Great Plains,

but formerly had a much larger range including much of the eastern

United States and parts of Mexico. Both species were hunted close to extinction

during the 19th and 20th centuries, but have since rebounded; the

wisent owing its survival, in part, to the Chernobyl Disaster,

ironically, as the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone has become a kind of wildlife preserve for wisent and other rare megafauna such as the Przewalski's Horse, though poaching has become a threat in recent years. The American Plains bison is no longer listed as endangered, but this does not mean the species is secure. Genetically pure B. b. bison currently number only ~20,000, separated into fragmented herds—all of which require active conservation measures. The Wood bison is on the endangered species list in Canada

and is listed as threatened in the United States, though there have

been numerous attempts by beefalo ranchers to have it entirely removed

from the Endangered Species List.

A museum display shows the full skeleton of an adult male American Bison

Although superficially similar, physical and behavioural differences

exist between the American and European bison. The American species has

15 ribs, while the European bison has 14. The American bison has four

lumbar vertebrae, while the European has five.

(The difference in this case is that what would be the first lumbar

vertebra has ribs attached to it in American bison and is thus counted

as the 15th thoracic vertebra, compared to 14 thoracic vertebrae in

wisent.) Adult American bison are less slim in build and have shorter

legs. American bison tend to graze more, and browse

less than their European relatives. Their anatomies reflect this

behavioural difference; the American bison's head hangs lower than the

European's. The body of the American bison is typically hairier, though

its tail has less hair than that of the European bison. The horns of the

European bison point through the plane of their faces, making them more

adept at fighting through the interlocking of horns in the same manner

as domestic cattle, unlike the American bison, which favours butting. American bison are more easily tamed than their European cousins, and breed with domestic cattle more readily.

Evolution and genetic history

The bovine tribe (Bovini) split about 5 to 10 million years ago into the buffalos (Bubalus and Syncerus) and a group leading to bison and taurine cattle.

Thereafter, the family lineage of bison and taurine cattle does not

appear to be a straightforward "tree" structure as is often depicted in

much evolution, because evidence of interbreeding and crossbreeding is

seen between different species and members within this family, even many

millions of years after their ancestors separated into different

species. This crossbreeding was not sufficient to conflate the different

species back together, but it has resulted in unexpected relationships

between many members of this group, such as yak being related to

American bison, when such relationships would otherwise not be apparent.

A 2003 study of mitochondrial DNA indicated four distinct maternal lineages in tribe Bovini:

However, Y chromosome analysis associated wisent and American bison.

An earlier study using amplified fragment length polymorphism

fingerprinting showed a close association of wisent with American bison,

and probably with the yak, but noted that the interbreeding of Bovini

species made determining relationships problematic.

The genus Bison diverged from the lineage that led to cattle (Bos primigenius) at the Plio-Pleistocene boundary in South Asia. Two extant and six extinct species are recognised. Of the six extinct species, five went extinct in the Quaternary extinction event. Three were North American endemics: Bison antiquus, B. latifrons, and B. occidentalis. The fourth, B. priscus (steppe bison), ranged across steppe environments from Western Europe, through Central Asia, East Asia including Japan, and onto North America. The fifth, B. schoetensacki (woodland bison), inhabited Eurasian forests, extending from western Europe to the south of Siberia.

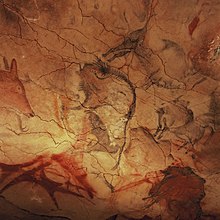

Bisons depicted at Cave of Altamira

The sixth, B. palaeosinensis, evolving in the Early Pleistocene in South Asia, is presumed to have been the evolutionary ancestor of B. priscus and all successive Bison lineages. The steppe bison (B. priscus) evolved from Bison palaeosinensis in the Early Pleistocene. B. priscus is seen clearly in the fossil record around 2 million years ago.

The steppe bison spread across Eurasia, and all proceeding contemporary

and successive species are believed to have derived from the steppe

bison. Going extinct in 6,000 BCE, outlasted only by B. occidentalis, B. bonasus and B. bison, the steppe bison was the predominant bison pictured in the ancient cave paintings of Spain and Southern France.

The modern European bison

is likely to have arisen from the steppe bison. There is no direct

fossil evidence of successive species between the steppe bison and the

European bison, though there are three possible lines of ancestry

pertaining to the European wisent. Past research has suggested that the

European bison is descended from bison that had migrated from Asia to

North America, and then back to Europe, where they crossbred with

existing steppe bison. However, more recent phylogenetic research points to an origin either from the phenotypically and genetically similar Pleistocene woodland bison (B. schoetensacki) or as the result of an interbreeding event between the steppe bison and the aurochs (Bos primigenius), the ancestor of domesticated cattle, around 120,000 years ago. The possible hybrid is referred to in vernacular as the 'Higgs bison' as a hat-tip to the discovery process of the Higgs boson.

At one point, some steppe bison crossbred with the ancestors of

the modern yak. After that crossbreeding, a population of steppe bison

crossed the Bering Land Bridge

to North America. The steppe bison spread through the northern parts of

North America and lived in Eurasia until around 11,000 years ago and North America until 4,000 to 8,000 years ago.

The Pleistocene woodland bison (B.schoetensacki) evolved in the Middle Pleistocene from B. priscus, and tended to inhabit the dry conifer forests and woodland which lined the mammoth steppe,

occupying a range from western Europe to the south of Siberia. Although

their fossil records are far rarer than their antecedent, they are

thought to have existed until at least 36,000 BCE.

Bison latifrons (the "giant" or "longhorn" bison) is thought to have evolved in midcontinent North America from B. priscus, after the steppe bison crossed into North America. Giant bison (B. latifrons) appeared in the fossil record about 120,000 years ago. B. latifrons was one of many species of North American megafauna that became extinct during the transition from the Pleistocene to the Holocene epoch

(an event referred to as the Quaternary extinction event). It is

thought to have disappeared some 21,000–30,000 years ago, during the

late Wisconsin glaciation.

B. latifrons co-existed with the slightly smaller B. antiquus

for over 100,000 years. Their predecessor, the steppe bison appeared in

the North American fossil record around 190,000 years ago. B. latifrons is believed to have been a more woodland-dwelling, non-herding species, while B. antiquus was a herding grassland-dweller, very much like its descendant B. bison. B. antiquus gave rise to both B. occidentalis, and later B. bison, the modern American bison, some 5,000 to 10,000 years ago. B. antiquus was the most common megafaunal species on the North American continent during much of the Late Pleistocene and is the most commonly found large animal found at the La Brea Tar Pits.

In 2016, DNA extracted from Bison priscus fossil remains beneath a 130,000-year-old volcanic ashfall in the Yukon

suggested recent arrival of the species. That genetic material

indicated that all American bison had a common ancestor 135,000 to

195,000 years ago, during which period the Bering Land Bridge was

exposed; this hypothesis precludes an earlier arrival. The researchers

sequenced mitochondrial genomes from both that specimen and from the

remains of a recently discovered, estimated 120,000-year-old giant,

long-horned, B. latifrons from Snowmass, Colorado. The genetic

information also indicated that a second, Pleistocene migration of bison

over the land bridge occurred 21,000 to 45,000 years ago.

Skulls of European bison (left) and American bison (right)

During the population bottleneck, after the great slaughter of

American bison during the 19th century, the number of bison remaining

alive in North America declined to as low as 541. During that period, a

handful of ranchers gathered remnants of the existing herds to save the

species from extinction. These ranchers bred some of the bison with

cattle in an effort to produce "cattleo" (today called "beefalo")

Accidental crossings were also known to occur. Generally, male domestic

bulls were crossed with buffalo cows, producing offspring of which only

the females were fertile. The crossbred animals did not demonstrate any

form of hybrid vigor, so the practice was abandoned. Wisent-American

bison hybrids were briefly experimented with in Germany (and found to be

fully fertile) and a herd of such animals is maintained in Russia. A

herd of cattle-wisent crossbreeds (zubron)

is maintained in Poland. First-generation crosses do not occur

naturally, requiring caesarean delivery. First-generation males are

infertile. The U.S. National Bison Association has adopted a code of

ethics that prohibits its members from deliberately crossbreeding bison

with any other species. In the United States, many ranchers are now

using DNA testing to cull the residual cattle genetics from their bison

herds. The proportion of cattle DNA that has been measured in

introgressed individuals and bison herds today is typically quite low,

ranging from 0.56 to 1.8%.

There are also remnant purebred American bison herds on public lands in North America. Herds of importance are found in Yellowstone National Park, Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota, Blue Mounds State Park in Minnesota, Elk Island National Park in Alberta, and Grasslands National Park in Saskatchewan. In 2015 a purebred herd of 350 individuals was identified on public lands in the Henry Mountains of southern Utah via genetic testing of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA. This study, published in 2015, also showed the Henry Mountains bison herd to be free of brucellosis, a bacterial disease that was imported with non-native domestic cattle to North America.

Behavior

A group of images by Eadweard Muybridge, set to motion to illustrate the movement of the bison

A bison charges an elk in Yellowstone National Park.

Wallowing

is a common behavior of bison. A bison wallow is a shallow depression

in the soil, either wet or dry. Bison roll in these depressions,

covering themselves with mud or dust. Possible explanations suggested

for wallowing behavior include grooming behavior associated with

moulting, male-male interaction (typically rutting behavior), social behavior for group cohesion, play behavior, relief from skin irritation due to biting insects, reduction of ectoparasite load (ticks and lice), and thermoregulation. In the process of wallowing, bison may become infected by the fatal disease anthrax, which may occur naturally in the soil.

Bison temperament is often unpredictable. They usually appear

peaceful, unconcerned, even lazy, yet they may attack anything, often

without warning or apparent reason. They can move at speeds up to 35 mph

(56 km/h) and cover long distances at a lumbering gallop.

Their most obvious weapons are the horns borne by both males and

females, but their massive heads can be used as battering rams,

effectively using the momentum produced by what is a typical weight of

2,000 pounds (900 kg) (can be up to 2700 lbs) moving at 30 mph

(50 km/h). The hind legs can also be used to kill or maim with

devastating effect. In the words of early naturalists, they were

dangerous, savage animals that feared no other animal and in prime

condition could best any foe (except for wolves and brown bears).

The rutting, or mating, season lasts from June through September,

with peak activity in July and August. At this time, the older bulls

rejoin the herd, and fights often take place between bulls. The herd

exhibits much restlessness during breeding season. The animals are

belligerent, unpredictable, and most dangerous.

Habitat

"Last of the Canadian Buffaloes", 1902, photograph: Steele and Company

American bison live in river valleys, and on prairies and plains.

Typical habitat is open or semiopen grasslands, as well as sagebrush,

semiarid lands, and scrublands. Some lightly wooded areas are also known

historically to have supported bison. They also graze in hilly or

mountainous areas where the slopes are not steep. Though not

particularly known as high-altitude animals, bison in the Yellowstone Park bison herd are frequently found at elevations above 8,000 feet and the Henry Mountains bison herd

is found on the plains around the Henry Mountains, Utah, as well as in

mountain valleys of the Henry Mountains to an altitude of 10,000 feet.

European bison tend to live in lightly wooded to fully wooded

areas and areas with increased shrubs and bushes, though they can also

live on grasslands and plains.

Restrictions

Throughout

most of their historical range, landowners have sought restrictions on

free-ranging bison. Herds on private land are required to be fenced in.

In the state of Montana, free-ranging bison on public lands may be

shot, due to concerns about transmission of disease to cattle and damage

to public property.

In 2013, Montana legislative measures concerning the bison were

proposed and passed the legislature, but opposed by Native American

tribes as they impinged on sovereign tribal rights. Three such bills

were vetoed by Steve Bullock,

the governor of Montana. The bison's circumstances remain an issue of

contention between Native American tribes and private landowners.

Diet

A bison and an elk grazing together in the Yellowstone National Park.

Bison are ruminants,

which allows them to derive their energy from cell walls. Bison were

once thought to almost exclusively consume grasses and sedges, but are

now known to consume a wide-variety of plants including woody plants and

herbaceous eudicots.

Over the course of the year, bison shift which plants they select in

their diet based on which plants have the highest protein or energy

concentrations at a given time and will reliably consume the same

species of plants across years.

Protein concentrations of the plants they eat tend to be highest in the

spring and decline thereafter, reaching their lowest in the winter.

In Yellowstone National Park, bison browsed willows and cottonwoods,

not only in the winter when few other plants are available, but also in

the summer. Bison are thought to migrate to optimize their diet, and will concentrate their feeding on recently burned areas due to the higher quality forage the regrows after the burn.

Wisent tend to browse on shrubs and low-hanging trees more often than

do the American bison, which prefer grass to shrubbery and trees.

Reproduction

Female bison typically do not reproduce until three years of age and can reproduce to at least 19 years of age.

Female bison can produce calves annually as long as their nutrition is

sufficient, but will not give birth to a calf after years where weight

gain was too low. A mother's probability of reproduction the following

year is strongly dependent on the mother's mass and age.

Heavier female bison produce heavier calves (weighed in the fall at

weaning) than light mothers, while the weight of calves is lower for

older mothers (after age 8).

Predators

Wolves hunting bison

Due to their size, bison have few predators. Five notable exceptions are humans, the wolf, mountain lion, brown bear, and coyote. The grey wolf generally takes down a bison while in a pack, but cases of a single wolf killing bison have been reported. Brown bear also consume bison, often by driving off the pack and consuming the wolves' kill. Brown bear and coyotes also prey on bison calves. Historically and prehistorically, lions, tigers, Smilodon, Homotherium, cave hyenas and Homo sp. had posed threats to bison.

Infections and illness

For the American bison, the main cause of illness is malignant catarrhal fever, though brucellosis is a serious concern in the Yellowstone Park bison herd. Bison in the Antelope Island bison herd are regularly inoculated against brucellosis, parasites, Clostridium infection, infectious bovine rhinotracheitis, and bovine vibriosis.

The major concerns for illness in European bison are

foot-and-mouth disease and balanoposthitis, which affects the male sex

organs; a number of parasitic diseases have also been cited as threats.

The inbreeding of the species caused by the small population plays a

role in a number of genetic defects and immunity to diseases, which in

turn poses greater risks to the population.

Name

The term "buffalo" is sometimes considered to be a misnomer for this animal, as it is only distantly related to either of the two "true buffalo", the Asian water buffalo and the African buffalo. Samuel de Champlain applied the term buffalo (buffles in French) to the bison in 1616 (published 1619), after seeing skins and a drawing shown to him by members of the Nipissing First Nation, who said they travelled forty days (from east of Lake Huron) to trade with another nation who hunted the animals.

Though "bison" might be considered more scientifically correct, as a

result of standard usage, "buffalo" is also considered correct and is

listed in many dictionaries as an acceptable name for American buffalo

or bison. Buffalo has a much longer history than bison, which was first

recorded in 1774.

Human impact

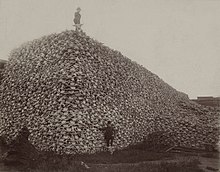

Photo from the 1870s of a pile of American bison skulls waiting to be ground for fertilizer.

Humans were almost exclusively accountable for the near-extinction of

the American bison in the 1800s. At the beginning of the century, tens

of millions of bison roamed North America. American settlers slaughtered

an estimated 50 million bison during the 19th century.

Railroads were advertising "hunting by rail", where trains encountered

large herds alongside or crossing the tracks. Men aboard fired from the

trains roof or windows, leaving countless animals to rot where they

died. The overhunting of the bison reduced their population to hundreds.

Attempts to revive the American bison have been highly successful;

farming has increased their population to nearly 150,000. The American

bison is, therefore, no longer considered an endangered species.

As of July 2015, an estimated 4,900 bison lived in Yellowstone National Park, the largest U.S. bison population on public land.

During 1983–1985 visitors experienced 33 bison-related injuries (range =

10–13/year), so the park implemented education campaigns. After years

of success, five injuries associated with bison encounters occurred in

2015, because visitors did not maintain the required distance of 75 ft

(23 m) from bison while hiking or taking pictures.

Nutrition

Bison is an excellent source of complete protein and a rich source

(20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of multiple vitamins including

Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, and Vitamin B12 and is also a rich

source of minerals including iron, phosphorus, and zinc. Additionally,

bison is a good source (10% or more of the Daily Value) of thiamine.

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 179 kcal (750 kJ) |

0.00 g

| |

| Sugars | 0 g |

| Dietary fiber | 0 g |

8.62 g

| |

| Saturated | 3.489 g |

| Monounsaturated | 3.293g |

| Polyunsaturated | 0.402 g |

25.45 g

| |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) |

12%

0.139 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

22%

0.264 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

40%

5.966 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

31%

0.401 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

4%

16 μg |

| Vitamin B12 |

102%

2.44 μg |

| Vitamin D |

0%

0 IU |

| Vitamin E |

1%

0.20 mg |

| Vitamin K |

1%

1.3 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium |

1%

14 mg |

| Iron |

25%

3.19 mg |

| Magnesium |

6%

23 mg |

| Phosphorus |

30%

213 mg |

| Potassium |

8%

353 mg |

| Sodium |

5%

76 mg |

| Zinc |

56%

5.34 mg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Livestock

Early

instances of pre-Columbian domestication of bison include reports by an

early Spanish source of domestication by Amerindians (including the

"milking" of bison), and Montezuma's zoo at Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, which included bison, which the Spaniards called "the Mexican bull."Bison are increasingly raised for meat, hide, wool, and dairy

products. The majority of bison in the world are raised for human

consumption or fur clothing. Bison meat is generally considered to taste

very similar to beef, but is lower in fat and cholesterol, yet higher in protein than beef, which has led to the development of beefalo, a fertile hybrid of bison and domestic cattle. A market even exists for kosher

bison meat; these bison are slaughtered at one of the few kosher mammal

slaughterhouses in the U.S. and Canada, and the meat is then

distributed worldwide.

In America, the commercial industry for bison has been slow to develop despite individuals, such as Ted Turner,

who have long marketed bison meat. In the 1990s, Turner found limited

success with restaurants for high-quality cuts of meat, which include

bison steaks and tenderloin. Lower-quality cuts suitable for hamburger and hot dogs have been described as "almost nonexistent".

This created a marketing problem for commercial farming because the

majority of usable meat, about 400 pounds for each bison, is suitable

for these products.

In 2003, the United States Department of Agriculture purchased $10

million worth of frozen overstock to save the industry, which would

later recover through better use of consumer marketing. Restaurants have played a role in popularizing bison meat, like Ted's Montana Grill, which added bison to their menus. Ruby Tuesday first offered bison on their menus in 2005.

In Canada, commercial bison farming began in the mid 1980s, concerning an unknown number of animals then.

The first census of the bison occurred in 1996, which recorded 45,235

bison on 745 farms, and grew to 195,728 bison on 1,898 farms for the

2006 census.

Several pet food companies use bison as a red meat alternative in dog foods. The companies producing these formulas include Natural Balance Pet Foods, Freshpet, The Blue Buffalo Company, Solid Gold, Canidae, and Taste of the Wild.